Radclyffe Hall

Marguerite Antonia Radclyffe-Hall, the second child of Radclyffe Radclyffe-Hall (1846–1898) and Mary Jane Sager (1854–1945) was born on 12th August 1880 at West Cliff, Bournemouth. The death of her elder sister in infancy left her as an only child.

Her parents divorced in 1883. According to her biographer, Michael Baker: "She rarely saw her father thereafter and was unloved by her volatile mother, who remarried in 1890. Her mother's third husband was Alberto Visetti, a professor of singing at the Royal College of Music. Despite showing a precocious musical talent, she received scant encouragement from her stepfather (though he did, it seems, make sexual advances towards her). Her education was fitful and she remained a chronic bad speller all her life."

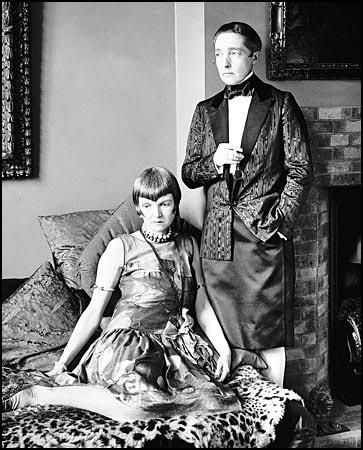

At the age of twenty-one she inherited a large sum of money that left in trust by her grandfather Charles Radclyffe-Hall. A lesbian, she lived with the singer Mabel Veronica Batten, who was twenty-five years her senior, until her death in 1916. Soon afterwards she began a relationship with Una Elena Troubridge (1887-1963), a talented sculptor. She was married to Admiral Ernest Troubridge and Radclyffe Hall sued him for libel after he described her as "a grossly immoral woman".

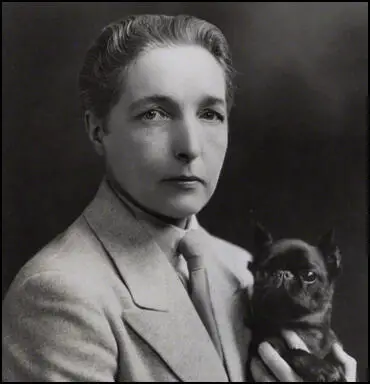

According to her biographer: "Believing herself a man trapped in a woman's body, she liked to be called John, assumed a male pseudonym (her father's name, significantly), and cultivated a strikingly masculine appearance, sporting cropped hair, monocles, bow-ties, smoking jackets, and pipes. A woman's best place, she proclaimed, was in the home."

Although she had enough money to live in leisure, Radclyffe Hall decided to take up writing and published several novels, including The Forge (1924), The Unlit Lamp (1924), A Saturday Life (1925) and several volumes of poetry. Her fourth novel, Adam's Breed (1926) was a best-seller and won two prestigious literary prizes, the Femina Vie Heureuse and James Tait Black.

In 1928 Radclyffe Hall published the novel, The Well of Loneliness, about the subject of lesbianism. The publisher, Jonathan Cape, argued on the bookjacket that: "In England hitherto the subject has not been treated frankly outside the regions of scientific text-books, but that its social consequences qualify a broader and more general treatment is likely to be the opinion of thoughtful and cultured people."

Havelock Ellis, the author of argued: "I have read The Well of Loneliness with great interest because - apart from its fine qualities as a novel - it possesses a notable psychological and sociological significance. So far as I know, it is the first English novel which presents, in a completely faithful and uncompromising form, one particular aspect of sexual life as it exists among us today. The relation of certain people - who, while different from their fellow human beings, are sometimes of the highest character and the finest aptitudes - to the often hostile society in which they move presents difficult and still unsolved problems. The poignant situations which thus arise are here set forth so vividly, and yet with such complete absence of offence, that we must place Radclyffe Hall's book on a high level of distinction."

There was a campaign by the press to get the book banned. The Sunday Express argued: "In order to prevent the contamination and corruption of English fiction it is the duty of the critic to make it impossible for any other novelist to repeat this outrage. I say deliberately that this novel is not fit to be sold by any bookseller or to be borrowed from any library."

Behind the scenes the Home Office put pressure of Jonathan Cape to withdraw the book. One official described the book as "inherently obscene… it supports a depraved practice and is gravely detrimental to the public interest". The chief magistrate, Sir Chartres Biron, ordered that all copies be destroyed, and that literary merit presented no grounds for defence. The publisher agreed to withdraw the novel and proofs intended for a publisher in France were seized in October 1928.

Several writers, including, Arnold Bennett, Vera Brittain, John Buchan, T.S. Eliot, E.M. Forster, Victor Gollancz, George Bernard Shaw, Lytton Strachey, Leonard Woolf, Virginia Woolf, Julian Huxley, Violet Markham, T.S. Eliot and Harley Granville-Barker, signed a letter of protest about the banning of the The Well of Loneliness to The Daily Chronicle.

Maude Royden, a woman preacher, gave passionate support for the book. A sermon on the subject was published in The Guildhall Monthly in April 1929. "I feel bound to say that I find it difficult to understand why an official who permits the publication of books so filthy that it soils the mind to read them, and the production of plays in which everything that is connected with sex is degraded, in which marriage and adultery alike are treated as though they were rather a nasty joke, should have fastened on this particular book as being unfit for us to read. I do not desire that those other books or plays should be suppressed; I have no faith at all in that way of dealing with evil. It is better to concentrate our efforts on trying to be interested in something that is good than to take a short cut to virtue by repressing what is evil."

Radclyffe Hall wrote to Maude Royden explaining her motivation for writing the novel: "May I take this opportunity of telling you how much your support of The Well of Loneliness has meant to its author during the past months of government persecution. I wrote the book in order to help a very much misunderstood and therefore unfortunate section of society, and to feel that a leader of thought like yourself had extended to me your understanding was, and still is, a source of strength and encouragement."

Radclyffe Hall followed The Well of Loneliness with The Master of the House (1932), Miss Ogilvie Finds Herself (1934) and The Sixth Beatitude (1936). Michael Baker has argued: "All these works, traditionalist in style but exhibiting an impressive psychological grasp, reflect in varying degrees her deep sense of being a social outsider and, increasingly, demonstrate her preoccupation with a search for spiritual self-knowledge through suffering and denial."

Although she continued to live with Una Elena Troubridge, Radclyffe Hall fell in love with a Russian nurse, Eugenie Souline in 1934. Despite the initial protests of Troubridge, the three women lived together in Florence. A staunch Roman Catholic she held right-wing opinions and during the late 1930s held neo-fascist and anti-semitic views.

On the outbreak of the Second World War, Radclyffe Hall, Ttoubridge and Souline left Italy and settled in Devon. Radclyffe Hall developed bowel cancer and died on 7th October 1943 at her flat in Pimlico. She was buried in Highgate Cemetery. Just before her death Hall changed her will, leaving everything to Troubridge, including the copyrights to her works. In her new will she asked Troubridge to "make such provision for our friend Eugenie Souline as in her absolute discretion she may consider right". However, Troubridge only provided Souline with only a small allowance.

Primary Sources

(1) The Sunday Express (19th August 1928)

The Well of Loneliness (Jonathan Cape, 15s. net) by Miss Radclyffe Hall, is a novel. The publishers state that it "handles very skilfully a psychological problem which needs to be understood in view of its growing importance"....

They declare that they "have been deeply impressed by this study"; they have felt that such a book should not be lost to those who may be willing and able to understand and appreciate it. They believe that the author has treated the subject in such a way as to combine perfect frankness and sincerity with delicacy and deep psychological insight.

In his prefatory "Commentary", Mr Havelock Ellis says:

"I have read The Well of Loneliness with great interest because - apart from its fine qualities as a novel - it possesses a notable psychological and sociological significance."

"So far as I know, it is the first English novel which presents, in a completely faithful and uncompromising form, one particular aspect of sexual life as it exists among us to-day."

"The relation of certain people - who, while different from their fellow human beings, are sometimes of the highest character and the finest aptitudes - to the often hostile society in which they move presents difficult and still unsolved problems."

"The poignant situations which thus arise are here set forth so vividly, and yet with such complete absence of offence, that we must place Radclyffe Hall's book on a high level of distinction."

That is the defence and justification of what I regard as an intolerable outrage - the first outrage of the kind in the annals of English fiction.

The defence is wholly unconvincing. The justification absolutely fails.

In order to prevent the contamination and corruption of English fiction it is the duty of the critic to make it impossible for any other novelist to repeat this outrage. I say deliberately that this novel is not fit to be sold by any bookseller or to be borrowed from any library.

(2) Maude Royden, The Guildhall Monthly (April 1929)

I am not going to speak tonight about the book called The Well of Loneliness which was during my absence abroad published here and then banned, but about the subject of that book. I do not suppose Miss Radclyfte-Hall desired the kind of advertisement that has been given to the book, but since it happened, and since the book has, largely in consequence of that advertisement, been very widely read, I feel bound to say that I find it difficult to understand why an official who permits the publication of books so filthy that it soils the mind to read them, and the production of plays in which everything that is connected with sex is degraded, in which marriage and adultery alike are treated as though they were rather a nasty joke, should have fastened on this particular book as being unfit for us to read. I do not desire that those other books or plays should be suppressed; I have no faith at all in that way of dealing with evil. It is better to concentrate our efforts on trying to be interested in something that is good than to take a short cut to virtue by repressing what is evil. But if there is to be censorship, why was this book chosen. I wish publicly to state that I honour the woman who wrote it, alike for her courage and her understanding; that I find her as just as she is merciful and as merciful as she is just; that her book seems to me to be altogether on the side of what is normal and right; and I do not understand how anyone can read that book patiently from start to finish, and not see that that is the conclusion of the matter.

These, however, are not reasons why I should preach about this book or on this subject. My reasons are these. The book is being very widely read. It is being widely read by members of this congregation, and by the younger members, who perhaps of all the people of my congregation are most - I will not say most clear to my heart, for all my congregation are clear - but most near to my conscience. And I have found that the advice frequently given by well-meaning, but almost incredibly ignorant people on this subject, is often tragic in its effect, not only on the lives of the abnormal but in the lives of others, normal or capable of becoming so.

What then is my subject? It is the fact that between people of the same sex friendship sometimes reaches a pitch of intensity which longs for physical contact, and for those intimacies and caresses which are normally only desired and only given between people of opposite sex. I do not say this love is more profound than any other kind of love, for the love of parents for their children, sometimes of brothers and sisters, sometimes of a more normal type of friendship, is sometimes quite as profound as the love of lovers. It may be, even in the life of a perfectly normal person, that the love of children is his - or more commonly her - ruling passion. But, even so, it has a different quality from sex-love; and it is this quality which sometimes exists between men for each other, and women for each other, and which creates the difficulties I speak of to-night.

If to some of you this "passionate friendship" seems quite incomprehensible, I ask you nevertheless to accept the fact that it does exist It is not even a new thing; it is not a consequence of the unnatural excitement and loneliness of the war and post-war periods.

I am going to assume tonight that what I call the "true" invert, the person who cannot be altered either by psychologists or physiologists does actually exist. His abnormality is not due to delayed or even arrested development: it is inherent and incurable. Whence do they come: "God made us," they reply: "what is he going to do with us"...

Consider - the invert can have no children and no home in our sense of the word. His love, which seems to him as sacred as yours and mine, must seem to the world horrible. He creates no new centre of life from which life conies into the world. There is no pull outward again when he turns inwards: the rhythm of creation is broken. When two lovers, a man and a woman, meet in marriage, their love turns into itself but it creates something, which draws them out again. The act of creation creates new life, and the parents' love is drawn out as the lovers' love was drawn in, and there is present the infolding and unfolding, the great and wonderful rhythm which runs through all life. But to the invert's love, this is impossible. The rhythm is broken. Love turns inwards and is locked there. The biological failure to create is paralleled by a spiritual failure. Need it be so, some of you ask? Cannot the love of the invert for his own sex, for her own sex, even though it be expressed physically, result in a spiritual creation? I do not think so. If it is to result in spiritual creation, it must be kept on a spiritual plane. If it yields to the desire for physical expression, it becomes spiritually valueless. Love is sacred - yes, all love is sacred. Let us never forger that. But love is

naturally creative and sterile love is a contradiction in terms. It is the function of love to create, just as it is tile function of hatred to destroy, for love is the very principle of creation, and to ask "Why did God create" is to ask a question without meaning. He creates because it is the nature of love to create. But when the invert argues that his love also may create spiritually, I think he falls into a fallacy; it creates spiritually only by the hard necessity of remaining a spiritual passion. I know the happiness that comes of a loneliness that is broken at last seems a release, and for a time there Is a sense of being satisfied; but that is all. Such love does not turn outwards to the creation of life, and it remains a secret.

I submit that the invert should accept the fact of his own nature and consequent suffering, and not try to escape it. This is the kind of thing I am ashamed to say, knowing how often I have sought and seek to escape pain. Have we not all tried to escape from suffering and loneliness? If I dare to say to the invert, "you must not try to escape, it is because I am certain that in one sense you cannot escape altogether." But it you accept your suffering, you will find that you are one of a great company. The form of your suffering is lonely, but the fact of your suffering is common, for all whose lives are worth living suffer - all of them. You will find yourself not alone in the deepest sense, for this great company of sufferers becomes to you more than a company; it is a communion, a communion of the deepest of human experiences. The experience of a pain that you accept and do not try to escape makes you one of that great host of martyrs, prophets and saints, in whose hearts there is always a cross. In this communion loneliness is transcended.

(3) Letter from Radclyffe Hall to Maude Royden (3rd January 1930)

May I take this opportunity of telling you how much your support of The Well of Loneliness has meant to its author during the past months of government persecution. I wrote the book in order to help a very much misunderstood and therefore unfortunate section of society, and to feel that a leader of thought like yourself had extended to me your understanding was, and still is, a source of strength and encouragement - thank you.