Frances Partridge

Frances Marshall, the third daughter and youngest of the six children of William Cecil Marshall (1849–1921) and his wife, Margaret Anna Lloyd (1863–1941), was born in Bedford Square, Bloomsbury on 15th March 1900. Her father was a successful architect and a keen sportsman who reached the final of the first Wimbledon tennis tournament. Her mother was a strong supporter of women's suffrage.

As a child she was a close friend of Julia Strachey, the daughter of Oliver Strachey and niece of Lytton Strachey. They both attended Bedales, the progressive co-educational school. Frances was already a pacifist and was a strong opponent of the First World War.

In 1918 Frances went to Newnham College, to read English. In her third year she changed to moral sciences and in 1921 gained the equivalent of an upper-second-class (at the time women were unable to receive Cambridge degrees). After leaving Cambridge University she went to work for her brother-in-law, David Garnett, the proprietor, with Francis Birrell, of the bookshop Birrell and Garnett. According to her biographer, Anne Chisholm: "She maintained a lifelong interest in philosophy, which she would read for pleasure. A slender girl with dark good looks and abundant vitality, she was an expert dancer much sought after as a partner."

Frances was invited to spend weekends with Virginia Woolf and Leonard Woolf at Charleston Farmhouse and Lytton Strachey and Dora Carrington at Mill House. She was soon an accepted member of the Bloomsbury Group. Other members of the group included Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster, Duncan Grant, David Garnett, Gerald Brenan, Roger Fry, Desmond MacCarthy and Arthur Waley.

Frances later recalled in her autobiography, Memories (1981): "They were not a group, but a number of very different individuals, who shared certain attitudes to life, and happened to be friends or lovers. To say they were unconventional suggests deliberate flouting of rules; it was rather that they were quite uninterested in conventions, but passionately in ideas. Generally speaking they were left-wing, atheists, pacifists in the First World War, lovers of the arts and travel, avid readers, Francophiles. Apart from the various occupations such as writing, painting, economics, which they pursued with dedication, what they enjoyed most was talk - talk of every description, from the most abstract to the most hilariously ribald and profane."

In 1921 Dora Carrington married Ralph Partridge. She wrote to Lytton Strachey on her honeymoon: "So now I shall never tell you I do care again. It goes after today somewhere deep down inside me, and I'll not resurrect it to hurt either you or Ralph. Never again. He knows I'm not in love with him... I cried last night to think of a savage cynical fate which had made it impossible for my love ever to be used by you. You never knew, or never will know the very big and devastating love I had for you ... I shall be with you in two weeks, how lovely that will be. And this summer we shall all be very happy together."

Carrington, Partridge and Strachey bought Ham Spray House in Ham, Wiltshire together. Frances was a regular visitor to their home. In her autobiography, Memories (1981), she commented: "Carrington loved the country and came rather seldom to London, so that I had seen little of her hitherto. Her unique personal flavour makes her extraordinarily difficult to describe, but fortunately she has painted her own portrait much better than anyone else could in her letters and diaries, which no-one can read without recognising her originality, fantastic imagination and humour." They all believed in free-love and Carrington began a passionate affair with Ralph's closest friend Gerald Brenan.

Michael De-la-Noy has pointed out: "It was not long before Frances Marshall found herself entangled in another extraordinary ménage à trois, at Tidmarsh, where Lytton Strachey was in love with the literary journalist Ralph Partridge, Partridge with the painter Dora Carrington, and Carrington, most improbably of all, with the quite obviously homosexual Strachey. Ralph and Carrington got married; then Ralph and Frances fell in love."

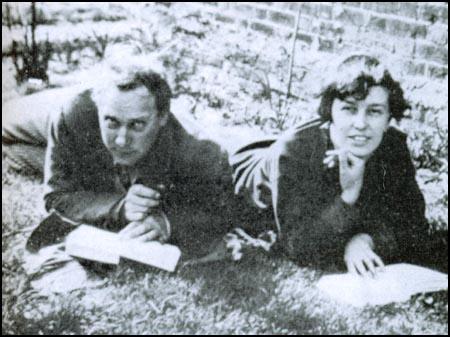

In 1926 Ralph Partridge left Dora Carrington and set up house with Frances Marshall in Gordon Square. As Anne Chisholm points out: "In 1928 Frances left the bookshop and started to work, with Ralph, on an unexpurgated edition of the Greville diaries, under Lytton Strachey's editorship." One biographer has argued: "This, inaccurately attributed to Strachey, was a mammoth scholarly task, and her work for it has not been sufficiently acknowledged. Every character mentioned had to be identified. It took nine years (until 1937) and the index alone was a volume of 300 double-column pages."

Lytton Strachey died of undiagnosed stomach cancer on 21st January 1932. His death made Dora Carrington suicidal. She wrote a passage from David Hume in her diary: "A man who retires from life does no harm to society. He only ceases to do good. I am not obliged to do a small good to society at the expense of a great harm to myself. Why then should I prolong a miserable existence... I believe that no man ever threw away life, while it was worth keeping."

Frances Marshall was with Ralph Partridge when he received a phone-call on 11th March 1932. "The telephone rang, waking us. It was Tom Francis, the gardener who came daily from Ham; he was suffering terribly from shock, but had the presence of mind to tell us exactly what had happened: Carrington had shot herself but was still alive. Ralph rang up the Hungerford doctor asking him to go out to Ham Spray immediately; then, stopping only to collect a trained nurse, and taking Bunny with us for support, we drove at breakneck speed down the Great West Road.... We found her propped on rugs on her bedroom floor; the doctor had not dared to move her, but she had touched him greatly by asking him to fortify himself with a glass of sherry. Very characteristically, she first told Ralph she longed to die, and then (seeing his agony of mind) that she would do her best to get well. She died that same afternoon."

Ralph and Frances were married on 2nd March 1933. Two years later their only child, Lytton Burgo Partridge, was born. Her friend, Nigel Nicolson, later commented: "It was as happy a marriage as any which is recorded, and the record is Frances's own diary. Without histrionics, she conveys the pleasure which each took in the other's company, the pleasure of travelling together, of sharing the same table and bed, of discussing without staleness the great moral and political issues of the day. Both loved music (and dancing: they once actually came second in the national ballroom championship) and literature. Both were agnostic, both became committed pacifists, Ralph in consequence of his experiences in the first world war, Frances as early as nine years old when she watched boys battering each other at Bedales."

According to The Times: "For the next 30 years, from their wedding in 1932, the marriage was extraordinarily close. Ralph, very good-looking, was highly intelligent and loyal, but not always easy. He had a formidable presence and loved arguing. Frances was his equal in debate, and never lost her head; and she could soothe him. More important were their intense interest in people and their highly developed senses of humour (Frances had a particularly delightful bubbling laugh). They talked about everything together, and for the last 28 years were never apart for more than a day. Few marriages can have been so enjoyable, not just for the lucky (and skilful) couple, but for their friends."

Frances Partridge became a full-time writer. This mainly involved translating books from French and Spanish. In 1942 Frances and the artist Richard Chopping were commissioned by Allen Lane to produce a 22-volume British Flora. In 1949 the project was cancelled. Although they were compensated, but it was seven years’ hard work wasted.

In 1960, after some years of poor health, Ralph Partridge died of a heart attack. Soon afterwards she left Ham Spray House for a small flat in Belgravia. Frances' son, Burgo married Henrietta, daughter of David Garnett and his second wife, Angelica Garnett, the illegitimate daughter of Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell. In 1963 Burgo, the father of a baby daughter, Sophie, also died following a heart-attack.

In 1978 Partridge published her first book, Pacifist War 1939-1945, an edited version of her Second World War diary. During the next two decades she published six more highly acclaimed volumes of her diaries: Everything to Lose: 1945-1960 (1985), Hanging On: 1960-1963 (1990), Other People: 1963-1966 (1993), Good Company: 1967-1970 (1994), Life Regained: 1970-1972 (1998) and Ups and Downs: 1972-1975 (2001). Other books included Memories (1981), and Julia (1983), a portrait of her friend, the author Julia Strachey and Friends in Focus (1987).

Frances Partridge died, aged 103, at her home in Belgravia (Flat 2, 15 West Halkin Street) on 5th February 2004. She was survived by her granddaughter, Sophie.

Primary Sources

(1) Frances Partridge, Memories (1981)

They were not a group (the Bloomsbury Group), but a number of very different individuals, who shared certain attitudes to life, and happened to be friends or lovers. To say they were unconventional suggests deliberate flouting of rules; it was rather that they were quite uninterested in conventions, but passionately in ideas. Generally speaking they were left-wing, atheists, pacifists in the First World War, lovers of the arts and travel, avid readers, Francophiles. Apart from the various occupations such as writing, painting, economics, which they pursued with dedication, what they enjoyed most was talk - talk of every description, from the most abstract to the most hilariously ribald and profane.

(2) Frances Partridge, diary entry (25th January, 1940)

Spent most of the morning reading Vera Brittain on Winifred Holtby - frightfully bad, but it aroused various reflections. It is a glorification of the second-rate and sentimental and reeks of femininity. Why should woman on woman so painfully lack irony, humour or bite? And it's too winsome and noble, somehow. But much of that belongs to the First War, and not to women only. (There it is in Rupert Brooke.) A musty aroma of danger glamourized and not understood by girls at home floats out of this book. Vera Brittain writes of the number of women now happily married and with children who still hark back to a khaki ghost which stands for the most acute and upsetting feelings they have ever had in their lives. Which is true I think, and the worst of it is that the ghost is often almost entirely a creature of their imagination.

(3) Frances Partridge, diary entry (6th July, 1940)

Gerald is now in trouble with the police. It seems he was out with the Home Guard a few nights ago, and used his electric torch to inspect the sandbag defences. A short time later several policemen rode up on motor bikes and shouted, "You were signalling to the enemy!" Gerald blew up and they became more reasonable, but he was later told, "We think it only fair to tell you we have reported you to Headquarters as signalling to the enemy". The head of the Aldboume Home Guard was sympathetic but thought nothing could be done. He quite agreed with Gerald that these were Gestapo methods - "Mind you, I think Fascism in one form or another has got to come." It seems to have come already. Gerald is thinking of resigning from the Home Guard and is very cynical about the hopeless confusion of our home defences.

(4) Frances Partridge, diary entry (6th July, 1940)

Mrs. Hill on the telephone again! "I've just heard that twenty refugees are arriving in half an hour. Could you have some more?" Raymond, Burgo and I drove down to the village and waited. Then the bus came lumbering in, and children ran to gape and stare. One very small child thudded alone screeching out "Vacuees! Vacuees!" As soon as they got out it was clear they were neither children nor docksiders, but respectable looking middle-aged women and a few children, who stood like sheep beside the bus looking infinitely pathetic. "Who'll take these?" "How many are you?" "Oh well, I can have these two but no more," and the piteous cry, "But we're together" It was terrible. I felt we were like sharp-nosed housewives haggling over fillets of fish. In the end we swept off two women about my age and a girl of ten, and then fetched the other two members of their party and installed them with Coombs the cowman. Their faces at once began to relax. Far from being terrified Londoners, they had been evacuated against their will from Bexhill, for fear of invasion, leaving snug little houses and "hubbies".

(5) Frances Partridge, diary entry (5th November, 1940)

Raymond and I went to see the Brenans. Gerald, back after his two weeks wardenship in London, looking young and lean. All the time he didn't see one person killed. Each night had its "incidents", houses demolished, people buried or cut by glass, or with all their clothes blown off shot up into trees, or starred all over with cuts from glass so as to be bright red with blood all over. The amount of blood was the one thing that struck him. Arthur Waley is a stretcher-bearer, and was called in when the Y.M.C.A. off Tottenham Court Road was hit. He said the whole place was swimming in blood and it was dripping down the stairs, yet hardly a person was killed. All were superficial cuts from glass. He believes that most people cannot resist the temptation to exaggerate. The really terrified people leave London or else go down to the tube others make themselves as safe as possible somewhere where they can sleep. And he says most people do manage to sleep now, and that many people are enjoying finding themselves braver than they knew.

(6) Frances Partridge, diary entry concerning the death of Virginia Woolf (8th April, 1941)

Sat out on the verandah, trying to write to Clive (Bell) in answer to his letter about Virginia's death. He says: "For some days, of course, we hoped against hope that she had wandered crazily away and might be discovered a barn or a village shop. But by now all hope is abandoned. It became evident some weeks ago that she was in for another of those long agonizing breakdowns of which she has had several already. The prospect - two years insanity, then to wake up to the sort of world which two years of war will have made, was such that I can't feel sure that she was unwise. Leonard, as you may suppose, is very calm and sensible. Vanessa is, apparently at least, less affected than Duncan (Grant), Ouentin and I had looked for and feared. I dreaded some such physical collapse as before her after Julian was killed. For the rest of us the loss is appalling, but like all unhappiness that comes of missing , I suspect we shall realize it only bit by bit."

(7) Frances Partridge, Memories (1981)

Why, I wonder, have writers paid so little honour to friendship? Sustaining, warming, refreshing and endlessly stimulating, it should surely have had almost as many poems written to it as have been dedicated to love. Yet I search anthologies and often find none.

Blood is thicker... well, in a sense it is true, but love of family is genetic and static in comparison: one is born possessing it, and though it may persist staunchly, and of course rates a plus sign in the vital arithmetic, its capacity for development is limited. The exciting truth about friendship is that it is founded on choice; its possibilities of growth and change are manifold. It fertilises the soil of one's life, sends up fresh shoots, encourages cross-pollination and the creation of new species.

(8) The Times (7th February, 2004)

In 1915 she went to Bedales. “Artiness and discomfort” was how she described it; she might have added dancing, friendship and talk - “endless talk”. For the first, Frances had considerable talent and, as with her activities all her life, abundant energy; for the other two she developed what amounted to passions. An atheist from the age of 12, she now became an equally convinced pacifist. This, considering the time, was remarkable evidence of maturity and independence.

Photographs of her at Cambridge, where she went after Bedales, show a slim, attractive figure in whose bright black eyes and sensitive mobile features humour, mischief and intelligence are set off by a certain reflective detachment. At Newnham, she read English for two years, and was much influenced by I.A. Richards. She then switched to moral sciences (philosophy, psychology and logic), completing a two-year course in one. Friends made for life there included Sebastian Sprott, George Rylands and Frank Ramsey, Wittgenstein’s brilliant colleague. There was more glorious talk, and there were admirers.

But it was in London that the horizon expanded. Frances first worked for Professor Cyril Burt, inventing and carrying out tests on Lyons waitresses to discover why they broke so much china. Then in 1922 David Garnett and Francis Birrell opened a bookshop in Taviton Street. Here the Woolfs and Bells, Stracheys and MacCarthys, Duncan Grant, E. M. Forster, Roger Fry and many others bought their books.

Partridge had met some of them before (Julia Strachey had been her best friend since the age of 9), and now she felt she had found a group where her passion for friendship and talk was reciprocated. She went to their weekend parties, to concerts and exhibitions; she danced and talked and fell lightly in love. She also met the traveller for the Hogarth Press, Ralph Partridge.

By 1925, after a relentless but irresistible siege, she was in love, not lightly at all, and living with him. She had entered a period the events of which now seem, so often have they been described, as much a part of literature as of life. It is enough to say that the complex manoeuvres involved would often not have been possible but for Frances’s generosity, good sense and tact; and Ralph, strong as he was, could scarcely have endured the last terrible months of Lytton Strachey’ s death and Carrington’s suicide.

For the next 30 years, from their wedding in 1932, the marriage was extraordinarily close. Ralph, very good-looking, was highly intelligent and loyal, but not always easy. He had a formidable presence and loved arguing. Frances was his equal in debate, and never lost her head; and she could soothe him. More important were their intense interest in people and their highly developed senses of humour (Frances had a particularly delightful bubbling laugh). They talked about everything together, and for the last 28 years were never apart for more than a day. Few marriages can have been so enjoyable, not just for the lucky (and skilful) couple, but for their friends....

Weekends were a different matter. There were four large and delicious meals a day (tea was nothing less than a meal). Guests were left to themselves in the mornings, but throughout there would be regular, analytical and humorous dissection of friends and their doings, which gave the feeling that Ham Spray was a civilised haven from the difficulties of life. On summer afternoons there was naked bathing in the minute poo1, badminton and walking on the Downs; in winter there were fires, books and the Sunday papers. For newcomers, it could be challenging. Frances was a rationalist; she was also affected by her emotions to a greater extent, perhaps, than she was aware. And she and Ralph had perfected the Bloomsbury art of conversational questioning.

(9) Nigel Nicolson, The Guardian (9th February, 2004)

It was as happy a marriage as any which is recorded, and the record is Frances's own diary. Without histrionics, she conveys the pleasure which each took in the other's company, the pleasure of travelling together, of sharing the same table and bed, of discussing without staleness the great moral and political issues of the day. Both loved music (and dancing: they once actually came second in the national ballroom championship) and literature. Both were agnostic, both became committed pacifists, Ralph in consequence of his experiences in the first world war, Frances as early as nine years old when she watched boys battering each other at Bedales.

They lived at Ham Spray throughout the second world war. It was for them A Pacifist's War, as she titled her first book (1978), but they managed to reconcile their abomination of the conflict with providing an occasional refuge for those who were doing their best to win it. Whether it was the arrival of the pig-sticker or her rediscovery of the violin and chamber music, her vivid recall delighted a new generation of friends.

Ham Spray was their home till 1960, when Ralph Partridge died. Neither wished to achieve very much except to create their own brand of happiness and spread it to their friends. Together they did a vast amount of work to help Lytton Strachey edit the unexpurgated edition of the memoirs of the 19th-century political diarist Charles Greville, publishing it in eight volumes in 1938, and Ralph had worked for a time with the Woolfs as an assistant at the Hogarth Press.

(10) Michael De-la-Noy, The Independent (20th April, 2009)

Born Frances Marshall in 1900, the youngest of a family of six reared to regard Charles Darwin as God and atheism as perfectly normal, she was educated at Bedales and at Newnham College, Cambridge, where initially she read English, switching to Moral Sciences, a tripos consisting of Philosophy, Psychology, Ethics and Logic. She was drawn to what was then the novel idea of a career in applied psychology, but unable to find serious paid employment for which she was qualified she applied for a job, at £3 a week, in the bookshop in Taviton Street run by David Garnett and Francis Birrell.

Thus it was only a matter of time before she met Virginia and Leonard Woolf, Maynard Keynes, Desmond and Molly MacCarthy, Lord David Cecil, Saxon Sydney-Turner - all those who already had the entrée to Lytton Strachey's rented house at Tidmarsh and to Charleston in Sussex, the informally run farmhouse inhabited on a most unorthodox basis by Clive and Vanessa Bell and Vanessa Bell's bisexual lover Duncan Grant, for many years the unacknowledged father of Angelica Garnett.

It was not long before Frances Marshall found herself entangled in another extraordinary ménage à trois, at Tidmarsh, where Lytton Strachey was in love with the literary journalist Ralph Partridge, Partridge with the painter Dora Carrington, and Carrington, most improbably of all, with the quite obviously homosexual Strachey. Ralph and Carrington got married; then Ralph and Frances fell in love.

The appalling drama that enabled Ralph and Frances eventually to marry was played out at Ham Spray, in Wiltshire, the house to which Ralph Partridge and Lytton Strachey had moved as joint owners. Carrington had remained devoted to Strachey, and when, in 1932, he died from cancer she became determined to commit suicide, only succeeding after a hideously bungled attempt to shoot herself.

(11) Matthew Dennison, The Telegraph (20th April, 2009)

Family connections meant that Frances was no stranger to the Bloomsbury set. Post-Cambridge, she took a job at Bloomsbury booksellers Birrell and Garnett and embarked on a round of parties attended by all the movement’s major players.

At such a party she met her future husband, Ralph Partridge. He pursued her with ardour, despite his marriage to the painter Dora Carrington and the couple’s emotionally volatile ménage à trois with Lytton Strachey. It would be 10 years before Ralph and Frances were formally married. That period witnessed the effective collapse of the Strachey/Carrington/Partridge ménage, Strachey’s death from cancer, Carrington’s suicide and the polarisation of opinion about Frances herself within Bloomsbury ranks. It was the experiences of this period that consolidated Frances’s status as a Bloomsbury insider despite her virtual exclusion from the Charleston realm of artistic and sexual experimentation.

Bloomsbury has consistently provoked strong reactions. Both Ralph and Frances admired it: “How inspiring and exciting?… were its standards.” By temperament and outlook, and as a result of her diary-keeping, Frances was the ideal candidate to become Bloomsbury’s spokeswoman through the long years of the movement’s neglect and its subsequent reversal of critical fortunes. It was an occupation which would last her all her life.