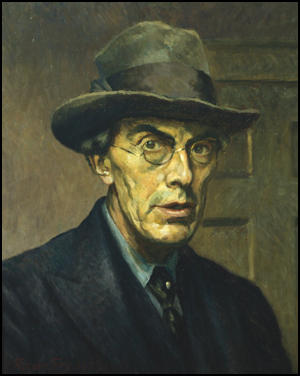

Roger Fry

Roger Eliot Fry, the fifth of the nine children of Sir Edward Fry (1827–1918), and his wife, Mariabella Hodgkin (1833–1930), was born on 14th December 1866 at Highgate. His father was a descendant of Joseph Fry, who established J S Fry & Sons. The family were also members of the Society of Friends.

Fry was initially educated at home but later became a student at Clifton College (1877-1881). He achieved good results and won a science exhibition at King's College in 1884. The following year he began studying natural sciences.

While at the University of Cambridge he developed a strong bond with Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, a young political science lecturer. He also began to take an interest in the writings of John Ruskin. His interest in political philosophy brought him into contact with Edward Carpenter and George Bernard Shaw.

Roger Fry left university in 1889 and moved to London where he trained as an artist under Francis Bate. In 1891 he made his first trip to Italy and studied briefly at the Académie Julian in Paris, where he discovered the Impressionists. During this period he experimented with several different styles. He married the artist, Helen Coombe, the daughter of a corn merchant, on 3rd December 1896. She gave birth to a son, Julian (1901) and daughter Pamela (1902).

Robert Trevelyan, an art collector, began buying Fry's work. Trevelyan told Paul Nash that "Fry was without doubt the high priest of art of the day, and could and did make artistic reputations overnight." Soon afterwards he became a tutor at the Slade Art School. His students included C.R.W. Nevinson, Stanley Spencer, Mark Gertler, John S. Currie, Dora Carrington, Dorothy Brett, Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot, Edward Wadsworth, Adrian Allinson and Rudolph Ihlee.

Fry met Clive Bell in a railway carriage between Cambridge and London. His sister-in-law, Virginia Woolf, later recalled: "It must have been in 1910 I suppose that Clive one evening rushed upstairs in a state of the highest excitement. He had just had one of the most interesting conversations of his life. It was with Roger Fry. They had been discussing the theory of art for hours. He thought Roger Fry the most interesting person he had met since Cambridge days. So Roger appeared. He appeared, I seem to think, in a large ulster coat, every pocket of which was stuffed with a book, a paint box or something intriguing; special tips which he had bought from a little man in a back street; he had canvases under his arms; his hair flew; his eyes glowed."

Fry also became an important member of the Bloomsbury Group, that met to discuss literary and artistic issues. Virginia Woolf commented that "he had more knowledge and experience than the rest of us put together". Other members of the group included Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster, Duncan Grant, Lytton Strachey, Vita Sackville-West, Ottoline Morrell, Bertram Russell, Leonard Woolf, David Garnett, Desmond MacCarthy and Arthur Waley.

Fry took a keen interest in all forms of art. In May 1910 he wrote an article for The Burlington Magazine on drawings by African Bushman, where he praised their sharpness of perception and intelligence of design. David Boyd Haycock argued that "Fry was opening up his awareness to a wider sphere of artistic expression, though it was not one that would win him many friends." Henry Tonks remarked to a friend: "Don't you think Fry might find something more interesting to write about than Bushmen."

Later that year Fry, Clive Bell and Desmond MacCarthy went to Paris and after visiting "Parisian dealers and private collectors, arranging an assortment of paintings to exhibit at the Grafton Galleries" in Mayfair. This included a selection of paintings by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, Édouard Manet, Paul Gauguin, André Derain and Vincent Van Gogh. As the author of Crisis of Brilliance (2009) has pointed out: "Although some of these paintings were already twenty or even thirty years old - and four of the five major artists represented were dead - they were new to most Londoners." This exhibition had a marked impression on the work of Duncan Grant, Vanessa Bell and Spencer Gore.

Henry Tonks, one of Britain's leading artists and the most important teacher at the Slade Art School, told his students that although he could not prevent them visiting the Grafton Galleries, he could tell them "how very much better pleased he would be if we did not risk contamination but stayed away". The critic for The Pall Mall Gazette described the paintings as the "output of a lunatic asylum". Robert Ross of The Morning Post agreed claiming the "emotions of these painters... are of no interest except to the student of pathology and the specialist in abnormality". These comments were especially hurtful to Fry as his wife had recently been committed to an institution suffering from schizophrenia.

Paul Nash recalled that he saw Claude Phillips, the art critic of The Daily Telegraph, on leaving the exhibition, "threw down his catalogue upon the threshold of the Grafton Galleries and stamped on it." William Rothenstein also disliked Fry's post-impressionist exhibition. He wrote in his autobiography, Men and Memories (1932) that he feared that the excessive publicity that the exhibition received, would seduce younger artists from "more personal, more scrupulous work".

In the spring of 1911 Fry went on holiday to Turkey with Vanessa Bell and Clive Bell. During her stay Vanessa had a miscarriage and a mental breakdown. Virginia Woolf went out to help nurse her. She was also going through a period of depression. She wrote: "To be 29 and unmarried - to be a failure - childless - insane too, no writer." Both Vanessa and Virginia fell in love with Fry. That summer Vanessa began an affair with Fry. They tried to keep in secret from Virginia but on 18th January 1912, Vanessa wrote to Fry: "Virginia told me last night that she suspected me of having a liaison with you. She has been quick to suspect it, hasn't she?" Knowledge of the affair was a major influence on why Virginia decided to marry Leonard Woolf.

Fry selected paintings for the exhibition entitled "British, French and Russian Artists" that was held at the Grafton Galleries, between October 1912 and January 1913. Artists included in the exhibition included Fry, Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant, Percy Wyndham Lewis, Spencer Gore, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne and Wassily Kandinsky. According to David Boyd Haycock: "Fry's second exhibition was not as badly received as the first. The intervening two years had seen a number of avant-garde shows in London, highlighting the work of continental modernism, and the art world was suddenly awash with isms."

In 1913 Fry joined with Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant to form the Omega Workshops. Other artists involved included Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Edward Wadsworth, Percy Wyndham Lewis and Frederick Etchells. Fry's biographer, Anne-Pascale Bruneau has suggested that: "It was an ideal platform for experimentation in abstract design, and for cross-fertilization between fine and applied arts."

Gretchen Gerzina has argued: "The Omega Workshops were the scene for some interesting - and sometimes volatile - conjunctions of personality and ideas. Their aim was to make art, through decoration, part of everyday life, and to provide both a workplace and an income for talented but hungry artists. Roger Fry had started the Omega in 1913 with these aims in mind and when it closed in 1919, he had substantially achieved them, despite commercial failure. The two Post-Impressionist Exhibitions which preceded its opening had given the artists a sense of imaginative freedom which canvas painting could not always express. Whole rooms, and all the objects within them, became their canvasses as they turned their brushes to textiles, dishes, screens, furniture and walls."

The art critic, Richard Cork, has pointed out: "He (Percy Wyndham Lewis) executed a painted screen, some lampshade designs, and studies for rugs, but his dissatisfaction with the Omega soon erupted into antagonism. No longer willing to be dominated by Fry, Lewis abruptly left the Omega with Edward Wadsworth, Cuthbert Hamilton, and Frederick Etchells in October 1913. By the end of the year he had begun to define an alternative to Fry's exclusive concentration on modern French art." This new movement became known as Vorticism.

Fry continued as a member of the Bloomsbury Group. One of its new members, Frances Partridge, later recalled in her autobiography, Memories (1981): "They were not a group, but a number of very different individuals, who shared certain attitudes to life, and happened to be friends or lovers. To say they were unconventional suggests deliberate flouting of rules; it was rather that they were quite uninterested in conventions, but passionately in ideas. Generally speaking they were left-wing, atheists, pacifists in the First World War, lovers of the arts and travel, avid readers, Francophiles. Apart from the various occupations such as writing, painting, economics, which they pursued with dedication, what they enjoyed most was talk - talk of every description, from the most abstract to the most hilariously ribald and profane."

Virginia Woolf commented that Fry was the "flesh and blood" of the group. With Fry about there was "always some new idea afoot... there was always some new picture standing on a chair to be looked at, some new poet fished out of obscurity and stood in the light of day." David Boyd Haycock, the author of A Crisis of Brilliance (2009) has pointed out: "It was a thrilling moment, the coming together of a circle of glittering talents who would help to refashion England's literary and artistic culture for the next forty years, dragging it all too reluctantly into the voguish world of the Modern." Hermione Lee argued in her book, Virginia Woolf (1996) that "Fry's arrival changed Bloomsbury, culturally and emotionally - to use one of his favourite words - in its texture."

Fry had a tremendous influence on the development of Virginia Woolf. She said she would have dedicated To the Lighthouse (1927) to Fry if she "had thought it was good enough." In a letter to Fry after its publication Woolf pointed out, "besides all your surpassing private virtues, you have I think kept me on the right path, so far as writing goes, more than anyone."

According to his biographer, Anne-Pascale Bruneau: "Much to his regret, Fry was never in a position to support himself by painting, but he had an exceptional gift for criticism, and was to be remembered as an enthralling lecturer, with a deep, mellifluous voice.... The venues were varied, including local art societies as well as university lecture halls; later, during the 1930s, Fry repeatedly filled the 2000-seat auditorium of the Queen's Hall. His subjects ranged from the analysis of a specific artist or school to discussions of aesthetics and of the methods of art history." Frances Partridge commented: "Anyone who heard Roger Fry lecture on art must owe him an immense debt of pure pleasure, for he had the rare gift of conveying his own love for paintings, even when their attractions were not obvious, even when the slides were put in upside down."

Books by Fry included Vision and Design (1920), Transformations (1926), Cézanne (1927) and Henri Matisse (1930). It has been argued by Kenneth Clark, that Fry's lectures and books had by introducing post-impressionist painting, and a critical terminology to make sense of it, had done more than any other critic to draw British art into modernist styles.

Roger Fry broke his pelvis in a fall on the 7th September, 1934. He was taken to the Royal Free Hospital but died two days later following a heart-attack. Virginia Woolf wrote in her diary: "I feel dazed; very wooden... My head all stiff. I think the poverty of life now is what comes to me; and this blackish veil over everything."

Primary Sources

(1) (1)Virginia Woolf, Roger Fry (1940)

There they stood upon chairs - the pictures that were to be shown at the Grafton Gallery - bold, bright, impudent almost, in contrast with the Watts portrait of a beautiful Victorian lady that hung on the wall behind them. And there was Roger Fry, gazing at them, plunging his eyes into them as if he were a humming-bird hawk-moth hanging over a flower, quivering yet still. And then drawing a deep breath of satisfaction, he would turn to whoever it might be, eager for sympathy. Were you puzzled? But why? And he would explain that it was quite easy to make the transition from Watts to Picasso; there was no break, only a continuation. They were only pushing things a little further. He demonstrated; he persuaded; he argued ... So he talked in that gay crowded room, absorbed in what he was saying, quite unconscious of the impression he was making; fantastic yet reasonable, gentle yet fanatically obstinate, intolerant yet absolutely open-minded, and burning with the conviction that something very important was happening.

(2) (2)David Boyd Haycock,A Crisis of Brilliance (2009)

It was then, in early 1910, that Fry made some important new friends. It started with a chance meeting with the painter Vanessa Bell and her husband, the art critic Clive Bell. Vanessa was the daughter of the scholar and critic Sir Leslie Stephen, and had trained at the Royal Academy Schools and briefly, in 1905, at the Slade - though she had soon quit when she tired of Tonks's acid criticism. She had first met Fry in 1906, the year after she had founded the Friday Club, an exclusive meeting-point for young artists which included a number of former Slade students. Like Fry, Clive Bell was a Cambridge graduate, and had also spent time in Paris, where he had discovered the work of Matisse and Gauguin. When Vanessa first introduced her husband to Fry in 1910, the two men immediately discussed the idea of staging an exhibition in London of the latest French painters. Clive liked the idea, but thought it was so fantastic, that the chances of pulling it off seemed slim.

So, whilst the exhibition idea was temporarily shelved, Fry was introduced to the Bells' wider circle, which congregated in their Bloomsbury home at 46 Gordon Square. The group of friends included the painter Duncan Grant (who had also studied in Paris), the writers Leonard Woolf, Lvtton Strachev and E.M. Forster, the economist John Maynard Keynes and the philosopher Bertrand Russell. These young Cambridge graduates were hugely impressed by Fry's remarkable erudition and intense personality.

Vanessa's younger sister, Virginia, was particularly captivated. "He had more knowledge and experience than the rest of us put together", she later wrote (though William Rothenstein, by contrast, told Henry Nevinson that he considered Fry "a bit crazy").

(3) Frances Partridge, Memories (1981)

Anyone who heard Roger Fry lecture on art must owe him an immense debt of pure pleasure, for he had the rare gift of conveying his own love for paintings, even when their attractions were not obvious, even when the slides were put in upside down. But his admiration had limits. When I went to India a few years ago I saw exactly what he meant by "the nerveless and unctuous sinuosity of the rhythms" of Indian sculpture. I don't think he was ever reconciled to it. Yet his mind was much more "open" than most, and among his wilder beliefs were that Shakespeare's Sonnets were just as good in French as in English, and that if a doctor was going to do something particularly unpleasant to him a brick under the bed would absorb the pain. He was a keen chess-player, and sometimes got me to play with him. He liked to win, and generally did, but if the issue was in doubt he would say, "Oh, I don't think it was wise to move your bishop. Better go there with your knight", and that would do the trick. He was charming to children, enjoying talking to them and always taking their remarks seriously and laughing at their jokes.

(4) (4)Virginia Woolf, Moments of Being: Autobiographical Writings (2002)

Here I come to a question which I must leave to some other memoir writer to discuss - that is to say, if we take it for granted that Bloomsbury exists, what are the qualities that admit one to it, what are the qualities that expel one from it? Now at any rate between 1910 and 1914 many new members were admitted. It must have been in 1910 I suppose that Clive one evening rushed upstairs in a state of the highest excitement. He had just had one of the most interesting conversations of his life. It was with Roger Fry. They had been discussing the theory of art for hours. He thought Roger Fry the most interesting person he had met since Cambridge days. So Roger appeared. He appeared, I seem to think, in a large ulster coat, every pocket of which was stuffed with a book, a paint box or something intriguing; special tips which he had bought from a little man in a back street; he had canvases under his arms; his hair flew; his eyes glowed. He had more knowledge and experience than the rest of us put together. His mind seemed hooked on to life by an extraordinary number of attachments. We started talking about Marie-Claire. And at once we were all launched into a terrific argument about literature... We had to think the whole thing over again. The old skeleton arguments of primitive Bloomsbury about art and beauty put on flesh and blood.

(5) (5)Gretchen Gerzina, A Life of Dora Carrington: 1893-1932 (1989)

As her circle of friends widened to include Bloomsbury, Carrington found herself increasingly judged by others as well as judging herself. Younger than the rest, she had been influenced by the changes they had introduced into English art. After the first Post-Impressionist Exhibition, Bloomsbury artists increasingly turned their efforts toward decorative art. The Omega Workshops were the scene for some interesting - and sometimes volatile - conjunctions of personality and ideas. Their aim was to make art, through decoration, part of everyday life, and to provide both a workplace and an income for talented but hungry artists. Roger Fry had started the Omega in 1913 with these aims in mind and when it closed in 1919, he had substantially achieved them, despite commercial failure. The two Post-Impressionist Exhibitions which preceded its opening had given the artists a sense of imaginative freedom which canvas painting could not always express. Whole rooms, and all the objects within them, became their canvasses as they turned their brushes to textiles, dishes, screens, furniture and walls.

(6) (6)Virginia Woolf, diary (12th September, 1934)

Roger died on Sunday... I feel dazed; very wooden... My head all stiff. I think the poverty of life now is what comes to me; and this blackish veil over everything. Hot weather; a wind blowing. The substance gone out of everything. I don't think this is exaggerated. It'll come back I suppose.