John S. Currie

John Currie, the illegitimate son of an Irish father who worked as a railway labourer, was born at Chesterton, Newcastle under Lyme in 1884. His father returned to Ireland and he was brought up by his mother. After leaving school Currie painted ceramics in the Staffordshire Potteries before going to the Newcastle and Hanley Schools of Art where he won a British Institution Scholarship.

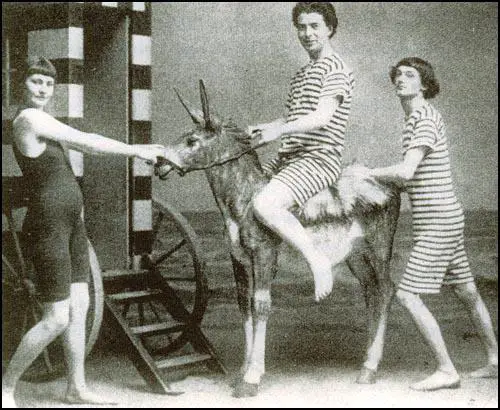

After receiving encouragement from Arnold Bennett he became an art teacher in Bristol. He married in 1907 and moved to London where he began selling some of his paintings. In the summer of 1910 he attended the Slade School of Art, where he made friends with a group of very talented students. This included C.R.W. Nevinson, Stanley Spencer, Mark Gertler, Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot, Edward Wadsworth, Adrian Allinson and Rudolph Ihlee. This group became known as the Coster Gang. According to David Boyd Haycock this was "because they mostly wore black jerseys, scarlet mufflers and black caps or hats like the costermongers who sold fruit and vegetables from carts in the street".

Currie became particularly close to Mark Gertler. According to David Boyd Haycock, the author of A Crisis of Brilliance (2009): "As an ambitious outsider attempting to escape an impoverished background, Currie had natural affinities with Gertler. Both shared a single-minded artistic drive... Like Gertler, Currie was dark-haired, but ruggedly handsome rather than pretty." Michael Sadleir, who met him during this period, commented that "he was simple and absorbed in his work - conscious of genius without being conceited, full of himself but not egoistic."

C.R.W. Nevinson argued in his autobiography, Paint and Prejudice (1937): "We were the terror of Soho and violent participants, for the mere love of a row... We also fought with the medical students of other hospitals... There is no doubt we behaved abominably and were no examples for placid modern youth." He also commented that the Coster Gang was "a crowd of men such as I have never seen before or since."

The Coster Gang's favourite hangout was the Petit Savoyard Café in Soho. Currie painted a picture of Madame Tisceron, the proprietor, and some members of the Coster Gang, entitled Some Later Primitives and Madame Tisceron, in a Renaissance style and an Italianate backdrop, in 1910.

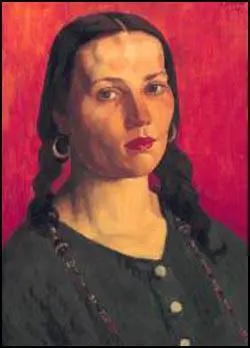

Currie met Dorothy Henry, a tall, attractive seventeen-year-old who modelled dresses at a Regent Street department store. Currie's friend and patron, Michael Sadleir, remarked that she "was of flower-like loveliness, but lascivious and possessive to the last degrees. Her lure for men were irresistible, and Currie was of course utterly enslaved to her physical attraction, a fact of which she was well aware." Currie's wife discovered the affair in August 1911 and he abandoned her and his young son and set-up home with Dolly in Primrose Hill.

David Boyd Haycock, the author of A Crisis of Brilliance (2009) has argued: "They were indifferent to public opinion - an independence of mind that impressed the young Gertler. But it was a hopelessly doomed relationship. Dolly was poorly educated, unintelligent, and had no interest in art. She resented Currie's absorption in his work, and attempted to make herself the centre of his life." Haycock quotes a friend who later recalled that Dolly used the power of her beauty and sexuality "to goad him from abject desire to baffled fury and then, suddenly complaisant, to win him back again. This dangerous cruelty led to violent quarrels and blows."

In July 1912, Currie, Dora Henry and Mark Gertler went on holiday to Ostend. They had a good time but Gertler showed concern about Currie's behavior. He suggested that Currie's love of the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche had left him immoral. Stanley Spencer strongly disliked Currie and said: "I cannot bear him." Adrian Allinson pointed out that Currie was insanely jealous of Dolly: "Violent jealously continually drove Currie to threats of murder... Dolly's beauty, and pity for her lot, aroused in more than one painter the desire to replace the Irishman, so that Currie's jealousy, originally groundless, in time created the conditions for its own justification."

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska introduced Currie to Edward Marsh, the great-grandson of Spencer Perceval,who was a major collector of modern art. He invited Currie to dinner at Gray's Inn. He brought Dolly Henry with him and Marsh described her as "an extremely pretty Irish girl with red hair". The following day he wrote to Rupert Brooke: "Currie came yesterday I have conceived a passion for both him and Gertler, they are decidedly two of the most interesting of les jeunes, and I can hardly wait till you come back to make their acquaintance." In August 1913 Marsh decided to spend an inheritance from an aunt on paintings by Currie, Mark Gertler and Stanley Spencer.

In December 1913 Currie, C.R.W. Nevinson and Mark Gertler exhibited at the Chenil Gallery. The art critic of The Sunday Observer commented that "when their modernity is closely investigated it seems to belong more to the fifteenth century than to the twentieth century." Eventually all three men abandoned this style. Nevinson described it as too "early Italian and custumy" and argued that "we must guard against raking up the past."

Gertler found Currie's behaviour increasing erratic and he told Dorothy Brett: "Friendships are terribly difficult to manage and I don't think they are worth the trouble. Henry is not intelligent at all - that's the trouble. Frankly I prefer to stand alone. I need no great friend at all. Ties are a terrible nuisance and hindrance to an artist." Currie was confused by Gertler's attitude and later told Edward Marsh, "Marsh's attitude to friends is rather curious - rather like mine to ladies... A strange and tormented lot we are."

Dolly Henry left Currie at the beginning of 1914. He gave a lecture on art at Leeds University soon afterwards. He told Michael Sadleir he was contemplating suicide. He explained that the main sources of his anguish was Dolly faithlessness, and his fear that his period of artistic genius had passed. Sadleir added: "His life was hell. But his love for her was intense."

In March 1914, Dolly agreed to return to Currie and they decided to move to Brittany. However, she returned after a few weeks. Currie explained to Edward Marsh what happened: "She had gone away friendly, but she was very much out of place here. Peasant life made her long for cafes and clubs in London. There are many good things in her, but all mv recent trouble in various ways might have been avoided had she better sense. The emotional and sexual horror and beauty of the whole damned thing - the months of torment and waste of energy, my loss of control, seems like a hell to me now."

Dolly Henry took a flat in Paultons Square, just off the King's Road. When Currie returned to London he heard rumours that Dolly had modelled for pornographic photographs and was spreading rumours about him in an attempt to ruin his career. Currie wrote to Dolly: "A very fury of remorse and love and sorrow is raging in me. I blame myself for everything. I am over-whelmed with self-disgust... As the days go on the feeling of all I have lost in you becomes so frightful I cannot breathe. I am looking for a place I can bury my heart and forget."

On 8th October 1914, Currie murdered Dolly Henry. The Times reported the following day. "A young woman, whose name is said to be Dorothy or Eileen Henry, was found fatally shot in a house in Chelsea... At a quarter to eight yesterday morning shots and screams were heard. The other occupants of the house ran upstairs and found the woman on the landing in her nightdress bleeding from wounds. In the bedroom a man partly dressed was discovered with wounds in the chest. He was taken to Chelsea infirmary, but the woman died before the arrival of a doctor." Currie died three days later. His final words were: "It was all so ugly".

Michael Sadleir later wrote: "Dolly drove Currie mad, and deprived the world of a genuine artist and a devoted worker. He was a man who, had circumstances been a little kinder, would have made a great reputation and lived a full an happy life."

Primary Sources

(1) Edward Marsh, letter to Rupert Brooke(26th August, 1913)

Currie came yesterday. I have conceived a passion for both him and Gertler, they are decidedly two of the most interesting of les jeunes, and I can hardly wait till you come back to make their acquaintance. Gertler is by birth an absolute little East End Jew. Directly I can get about I am going to see him in Bishopsgate and be initiated into the Ghetto. He is rather beautiful, and has a funny little shine black fringe, his mind is deep and simple, and I think he's got the feu sacre. He's only 22 - Currie I think a little older, and his pictures proportionately better, he can do what he wants, which Gertler can't quite yet, I think - but he will."

(2) Mark Gertler to Dorothy Brett (September 1913)

Friendships are terribly difficult to manage and I don't think they are worth the trouble. Dolly Henry is not intelligent at all - that's the trouble. Frankly I prefer to stand alone. I need no great friend at all. Ties are a terrible nuisance and hindrance to an artist. I know him far too well for that... he has friends and a woman whom he loves. Remember that I am absolutely alone and I have loved without the slightest success. If anyone will suffer it ought to be me. Perhaps no one of my age has suffered as much as I.

(3) John Currie to Edward Marsh (April 1914)

She had gone away friendly, but she was very much out of place here. Peasant life made her long for cafes and clubs in London. There are many good things in her, but all mv recent trouble in various ways might have been avoided had she better sense. The emotional and sexual horror and beauty of the whole damned thing - the months of torment and waste of energy, my loss of control, seems like a hell to me now.

(4) John Currie to Dolly Henry (October 1914)

A very fury of remorse and love and sorrow is raging in me. I blame myself for everything. I am over-whelmed with self-disgust... As the days go on the feeling of all I have lost in you becomes so frightful I cannot breathe. I am looking for a place I can bury my heart and forget.

(5) (5)Gretchen Gerzina, A Life of Dora Carrington: 1893-1932 (1989)

Gertler also told Cannan about his artist friend John Currie, who was the cause of a major tragedy in October of that year. His lover, Dolly Henry (whose real name was O'Henry), had moved away from him and found rooms of her own in Paulton Square, Chelsea. Currie went there one evening and they had a terrible argument, in which he shot her and then turned the gun on himself. She died immediately, and he died later in the Chelsea Infirmary, under police guard. Gertler visited him in the Infirmary shortly before he died, and the whole sordid affair deeply affected him. Currie, seven years older than Gertler, had been a mentor to him. He had had little respect for private property, and used to help himself to whatever he desired, even though it might be in a friend's home. He had read Nietzsche earnestly, and had had great self-confidence. He had lived openly with Dolly, and the two of them had taken Gertler to Paris with them, initiating him into great art, petty lovers' quarrels, and foreign culture, all at first hand. As he had done with everything Gertler had told him, Cannan had made careful note of these events and had romanticised them in his fiction.

(6) The Times (9th October 1914)

A young woman, whose name is said to be Dorothy or Eileen Henry, was found fatally shot in a house in Chelsea... At a quarter to eight yesterday morning shots and screams were heard. The other occupants of the house ran upstairs and found the woman on the landing in her nightdress bleeding from wounds. In the bedroom a man partly dressed was discovered with wounds in the chest. He was taken to Chelsea infirmary, but the woman died before the arrival of a doctor.