Stanley Spencer

Stanley Spencer, the son of William Spencer, a teacher of music, was born in Cookham, Berkshire, on 30th June 1891. He was the seventh son in a family of eleven children, of whom two died in infancy. The family lived in Fernlea, a semi-detached villa in Cookham High Street, that had been built by Stanley's grandfather, a local master builder.

When Spencer was seventeen he entered the Slade School of Fine Art at University College. Other students at the Slade at that time included Christopher Nevinson, Paul Nash, David Bomberg, William Roberts, Mark Gertler, Dora Carrington and Edward Wadsworth.

Spencer's skill as a artist is evident in early works such as The Fairy on the Waterlily Leaf (1910). One of his tutors, Henry Tonks argued that Spencer had the most original mind of any student he had the pleasure of teaching. At the Slade he won the Composition Prize with his painting The Nativity (1912). However, as his biographer, Fiona MacCarthy, points out: "His four years at the Slade were not altogether happy. He was marked out as a misfit by his physical appearance: his diminutiveness (he was only 5 feet 2 inches), his heavy fringe, and pudding-basin haircut. His aura of other-worldliness was enhanced by the fact that he commuted daily by train from Berkshire. He was known jeeringly as Cookham, and terrified by being put upside-down in a sack."

On the outbreak of the First World War, Spencer joined the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC). He worked at Beaufort Hospital in Bristol where he helped to nurse soldiers wounded on the Western Front. On 7th December 1915 he wrote to his friend, Henry Lamb: "Two hundred patients or more would arrive in the middle of the night - this was disquieting and disturbing. One had just got used to the patients one had; had mentally and imaginatively visualized them. I have to move patients with their beds from one ward to another or perhaps to the theatre."

In August 1916 he was sent as part of the 68th Field Ambulance unit to Salonika, a port being defended by General Maurice Sarrail and 150,000, British and French soldiers. In August 1917 he volunteered for the infantry, joining the 7th battalion, the Royal Berkshires, and spending several months in the front line. He later recalled: "Our activities consisted of outpost duty and patrolling the wire at night and during the daytime doing odd fatigues, just outside our dugouts. In the evening just before sunset, the Bulgars started a barrage. The shells dropped uncomfortably near and I was glad when getting into the outposts, we were able to take cover in a communication trench."

On one occasion he went out on patrol with one of the officers: "I went out with a captain and he was hit and sank to the ground. His hand went up to his neck and I saw a gaping bullet wound in it. I bandaged the wound the best I could and called for stretcher-bearers. I helped to support the captain, who was paralyzed." Spencer was devastated when he heard him whisper to another officer: "Understand, Spencer is not a fool; he is a damned good man." Spencer was shocked by what he heard: "What's all this? Who has been saying otherwise?"

In May, 1918, Spencer was asked to contribute to the government's planned Hall of Remembrance. The letter asked him to to paint a picture about his experiences in Salonika. However, it was not until after the Armistice that Spencer painted Travoys Arriving with Wounded at a Dressing Station at Smol, Macedonia, September 1916.

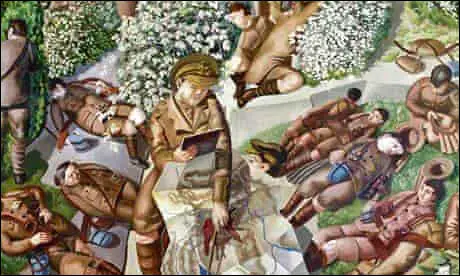

After the war Stanley Spencer was commissioned by Louis and Mary Behrend in memory of Mrs Behrend's brother Lieutenant Henry Willoughby Sandham to paint a decorative mural of army life during the First World War. Sandham had died in 1919 after an illness contracted in in Salonika. The nineteen paintings appeared in the Sandham Memorial Chapel in Burghclere, Hampshire. The work was painted as a modern parallel to Giotto's Arena Chapel in Padua. The cycle of scenes from everyday military life culminates in the altarpiece, Resurrection of the Soldiers.

Stanley Spencer painted The Resurrection, between 1924 and 1926 in a studio in Hampstead borrowed from Henry Lamb. When it was showed for the first time in February 1927 The Times critic described it as "the most important picture painted by any English artist in the present century… It is as if a Pre-Raphaelite had shaken hands with a Cubist". The painting was purchased by Joseph Duveen who then gave it to the Tate Gallery.

One critic argued that "Spencer believed that the divine rested in all creation. He saw his home town of Cookham as a paradise in which everything is invested with mystical significance. The local churchyard here becomes the setting for the resurrection of the dead. Christ is enthroned in the church porch, cradling three babies, with God the Father standing behind. Spencer himself appears near the centre, naked, leaning against a grave stone; his fiancée Hilda lies sleeping in a bed of ivy. At the top left, risen souls are transported to Heaven in the pleasure steamers that then ploughed the Thames."

While working on this cycle almost continuously between 1926 and 1932, Spencer lived in a cottage alongside the chapel with his wife, Hilda Carline (1889–1950) and their two daughters: Shirin (b. 1925) and Unity (b. 1930). The cultural historian, Fiona MacCarthy has argued: "The narrative of Stanley Spencer's war - the wounded arriving at Beaufort, the training camp at Tweseldown, the day-to-day routines of service in Macedonia - climaxes in the crowded, joyful central composition The Resurrection of the Soldiers covering the whole east wall. It is a highly personal sequence that transcends the anecdotal, treating the grand themes of glory and redemption in an extraordinary fusion of grandiloquence and homeliness."

After completing the Sandham Memorial Chapel Spencer and his young family moved to Lindworth, a house in Cookham. However, it was not a happy marriage and her passionate Christian Science principles seriously impaired their sex life. During this period Spencer became friendly with Patricia Preece who lived in Cookham with her friend and sexual partner Dorothy Hepworth. Hilda's refusal to accede to demands for a ménage à trois demanded by Spencer forced her eventually to file for a divorce which was granted on 25th May 1937.

Spencer married Preece four days later. They never lived together and according to Tee A. Corinne: "Spencer went into debt giving Preece money, clothing, and jewelry... Spencer then married Preece, but when he attempted to consummate the marriage, Preece immediately fled to Hepworth. Although Spencer and Preece never lived together as man and wife, they never divorced." Although the marriage was unconsummated, it did produce some remarkable nude portraits including Nude: Patricia Preece (1935), Self Portrait with Patricia Preece (1936) and Double Nude Portrait: the Artist and his Second Wife (1937).

Spencer continued to paint pictures of his marriage to Hilda Carline. This included Domestic Scenes: At the Chest of Draws (1936), The Beatitudes of Love (1937) and Romantic Meeting (1938). He also wrote her many letters but following a mental breakdown she was admitted to Banstead Mental Hospital in Epsom. Spencer gave his house in Cookham to Patricia Preece who rented it out in 1938, and he was forced to move to a rented room in Adelaide Road, Hampstead. Over the next few years he produced a series of paintings entitled Christ in the Wilderness (1939–53).

Soon after the outbreak of the Second World War the War Artists' Advisory Committee commissioned Spencer to record shipbuilding on the River Clyde. As his biographer, Fiona MacCarthy, points out: "His work was based at Lithgow's shipyard in Port Glasgow on the Firth of Clyde, concentrated on merchant ships under construction, and Spencer spent extended periods in Scotland during and immediately after the war. Spencer's war work came as a reprieve from his anxious isolation. He was able to immerse himself in the day-to-day activities of ordinary working people, intimately involved in the highly skilled processes of making with which he had always felt an innate sympathy. The Clyde shipbuilding paintings were conceived on an epic scale. Spencer's proposal was for a three-tier frieze 70 feet long. Eight of the projected thirteen canvases had been completed by the time the war artists were disbanded in 1946."

In September 1945 Spencer returned to Cookham, settling in Cliveden View, a small house belonging to his brother Percy Spencer. His former wife, Hilda Carline, died of breast cancer in 1950. He was devastated by the news and "he continued to write her his long, hectic, erotic, often incoherent letters." Over the next few years he completed a new cycle, Christ Preaching at Cookham Regatta (1955-1959).

In July 1959 he was knighted by Elizabeth II. His wife, Patricia Preece, now arrived back on the scene and took the title, Lady Spencer. Five months later, on 14 December 1959, Stanley Spencer died of cancer in the Canadian Red Cross Memorial Hospital at Taplow.

Primary Sources

(1) Stanley Spencer, letter to his friend Henry Lamb, who had recently decided to join the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC).

Do you know any decent regiment that would have me or Gil (his brother Gilbert Spencer)? We both feel it impossible to settle down, because to work at our job one has to enjoy things and I find it impossible. I think it is necessary for people like me to join. I am quite sure I am as strong as thousands who are fighting, and the beastly the stories become, the more I feel I ought to go to do something.

(2) In 1914 Stanley Spencer joined the RAMC and was sent to Beaufort Hospital in Bristol where he looked after injured soldiers from the Western Front. He wrote a letter to Henry Lamb, about his experiences on 7th December, 1915.

Two hundred patients or more would arrive in the middle of the night - this was disquieting and disturbing. One had just got used to the patients one had; had mentally and imaginatively visualized them. I have to move patients with their beds from one ward to another or perhaps to the theatre.

(3) Stanley Spencer, letter to Desmond Chute (January, 1917)

I do anything for these men. I cannot refuse them anything, and they love me to make drawings of photos of their wives and children or a brother who had been killed.

(4) Stanley Spencer wrote about his war experiences in a letter to Richard Carline in 1929.

My feelings about the Bulgars were acted upon in a very remarkable way, owing to the simple fact that I never saw them, and yet they were only a few yards away. They were the enemy - this gave me this feeling of remoteness from them - a feeling that they belonged to another planet. Some nights it was extraordinary to me to hear the ground crunching under the wheels of some cart when I was told it was the Bulgars' ration carts coming up, just as ours brought ours up.

Our activities consisted of outpost duty and patrolling the wire at night and during the daytime doing odd fatigues, just outside our dugouts. In the evening just before sunset, the Bulgars started a barrage. The shells dropped uncomfortably near and I was glad when getting into the outposts, we were able to take cover in a communication trench.

I went out with a captain and he was hit and sank to the ground. His hand went up to his neck and I saw a gaping bullet wound in it. I bandaged the wound the best I could and called for stretcher-bearers. I helped to support the captain, who was paralyzed and heard him whisper to another officer: "Understand, Spencer is not a fool; he is a damned good man." "What's all this? Who has been saying otherwise?"

(5) Letter from the Ministry of Information to Stanley Spencer (May, 1918)

Mr. Muirhead Bone, who takes a great interest in your work, has suggested that you should paint a picture under such title as A Religious Service at the Front, or any subjects in or about Salonika, which could be painted by you before you return home.

(6) In a letter to Hilda Carline in the summer of 1923, Stanley Spencer recalled how it got the idea for Travoys Arriving with Wounded at a Dressing Station at Smol, Macedonia, September 1916.

I was standing a little way from an old Greek Church, which was used as a dressing station, and coming there were these rows of travoys with wounded and limbers crammed full of wounded men. One would have thought that the scene was a sordid one, a terrible scene, but I felt there was a grandeur about it. All these wounded men were calm and at peace with everything, so the pain seemed a small thing with them. I felt there was a spiritual ascendancy over everything.