Arsenal Football Club : 1886-1960

David Danskin, Elijah Watkins, John Humble and Richard Pearce, were four friends who worked at Royal Arsenal in Woolwich, one of the government's main munition factories. In 1886 the four men decided to form a football club. According to Arthur Kennedy, who later became vice-chairman of the club: "football was practically unknown in the district, rugger holding the sway… In this year, however, a number of enthusiasts for the soccer code, who had migrated from the North and Midlands, conceived the idea of forming an association club, with the result that a meeting was held at the Royal Oak, Woolwich".

The Arsenal historian, Bernard Joy, claims that Danskin was the main person behind this move and sent a "subscription list around the workshops to obtain the first necessity, a football." Fifteen subscribed 6d. each and Danskin made up the total to 10s. 6d. out of his own pocket.

The club was initially called Dial Square, after one of the workshops. Danskin was captain of the side and Elijah Watkins agreed to be the secretary. Fred Beardsley and Joseph Bates, who both used to play for Nottingham Forest and who had only recently found work at the Woolwich Arsenal, agreed to join the club.

Michael Wade argues in The Arsenal Story: An Official History that: "The very first Arsenal side was, in effect, a works side, formed by people who earned their livings in a vast munitions factory... The first Arsenal football team owed more than its name to this place of work - the vast munitions factory helped to supply a steady flow of players, too. In the latter part of the 19th century, the factory was probably as busy as it ever had been, producing weaponry to bolster the forces of the British Empire and caught up in the escalating arms race that preceded the First World War."

The club had its first game against Eastern Wanderers on 11th December, 1886. Each man provided his own kit and they wore shirts and trousers of different colours. Three had shin guards and nearly all the boots were ordinary pairs, with bars nailed across the soles.

Dial Square won the game 6-0 but the players were not pleased with the quality of the pitch they played on. Elijah Watkins later reported: "Talk about a football pitch! This one eclipsed any I ever heard of or saw. I could not venture to say what shape it was, but it was bounded by backyards as to about two-thirds of the area, and the other portion was - I was going to say a ditch, but I think an open sewer would be more appropriate."

At a meeting at the Royal Oak soon afterwards, the men decided to rename the club Royal Arsenal. The club also agreed to play their home games on Plumstead Common and they changed into their football kit at the nearby Star public house.

The men could not afford to buy a football kit and so Fred Beardsley decided to write to his old club, Nottingham Forest, to ask them if they could help. The club generously agreed to send a complete set of red shirts.

David Danskin also managed to recruit other workers at the factory who had previous experience of playing football at a higher level in Scotland. This included Peter Connolly, Humphrey Babour, J. M. Charteris, John McBean and W. Scott. In 1888 Richard Horsington, who had previously played for Swindon Town, also joined the club.

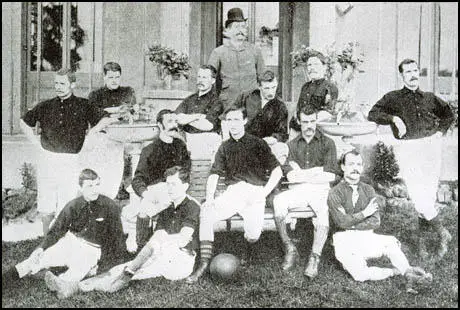

J. M. Charteris. Seated: Brown, Peter Connolly, David Danskin. Standing: Richard

Horsington, Wilson, Fred Beardsley, Joseph Bates, John McBean and William Scott.

The team continued to make progress and won the London Charity Cup in 1890 and the London Senior Cup in 1891. That year it was decided to change the club name from Royal Arsenal to Woolwich Arsenal.

A key player during his period was Humphrey Babour. He had previously played for or Third Lanark and Airdrie in the Scottish League. During his time at the club he scored 59 goals in 71 games. Another important goalscorer was J. M. Charteris who scored 24 goals in 28 games until he broke his leg in November 1890.

Woolwich Arsenal entered the FA Cup in 1892 but was knocked out by First Division side Derby County. At the end of the game, John Goodall, the captain and manager, attempted to sign two of Arsenal's players, Peter Connolly and Bobby Buist. As Arsenal was a non-league amateur club, there was nothing they could do to stop this happening.

John Humble, who had taken over from Elijah Watkins as Arsenal's secretary, was upset by this attempt to poach his best players and at the 1891 Annual General Meeting suggested that the club applied to join the Football League. The motion was carried by a large majority. However, Humble rejected the idea that Arsenal should become a limited company. Humble declared that "the club has been carried on by working men and it is my ambition to see it carried on by them."

(If you are enjoying this article, please feel free to share. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter and Google+ or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.)

The London Football Association immediately banned Arsenal from playing in their competitions. However, it was not until 1893 that Arsenal was elected to the Second Division of the Football League. It was decided that Arsenal needed to buy its own ground. The only way to raise enough money for this venture was to form a limited liability company. Eventually 860 people purchased 1,552 £1 shares in the club. Most of the shareholders were manual workers who lived locally.

In their first season Arsenal finished in 9th place in the Second Division. The best player was Harry Storer, the goalkeeper. In April 1895 he was chosen to play for the Football League against the Scottish League and therefore was the first Arsenal player to win representative honours. The following season Caesar Jenkyns became the club's first international player when he was selected to play for Wales against Scotland. Unfortunately both players were soon transferred to larger clubs. Storer was sold to Liverpool in December 1895 and Jenkyns went to Newton Heath in May 1896.

On 23rd November 1896, Joseph Powell, Arsenal's right-back, went to kick a high ball during a game against Kettering Town. His foot caught on the shoulder of an opponent and Powell fell and broke his arm. One of the men who went to his aid fainted at the sight of the protruding bone. Infection set in and, despite amputation above the elbow, Powell died a few days later when just twenty-six years of age.

Harry Bradshaw became the manager of Arsenal in 1901. One of his first signings was Jimmy Ashcroft from Gravesend United. He played in every game in the 1901-02 season and helped the club to their then highest ever league position (fourth in Division 2 of the Football League). As Jeff Harris points out in Arsenal Who's Who, Ashcroft let in "only twenty six goals in thirty four games of which he kept seventeen clean sheets which included a run of six games without conceding a goal (which still remains a club record)."

Bradshaw also purchased Roderick McEachrane and William Linward from West Ham United. Other players signed by the club during this period included Tommy Briercliffe, Tommy Shanks, Tim Coleman and Percy Sands.

Arsenal gradually built up a local following and over 25,000 people turned up to the Plumstead ground to play Sheffield United in the first round of the FA Cup.

In the 1903-04 season Jimmy Ashcroft conceded only 22 goals in 34 games. This included 20 clean sheets and he played a vital role in helping his club win promotion to the First Division. Tommy Shanks was the club's leading scorer with 25 league goals. This included hat-tricks against Leicester City, Lincoln City, Burnley and four in a game against Grimsby Town. Tim Coleman also scored 23 in 28 games.

In April 1904 Arsenal bought Charlie Satterthwaite from their London rivals, West Ham United. They also signed Bobby Templeton from Newcastle United for £375 in December 1904 to help them cope with First Division football. Arsenal did reasonably well at the top level finishing in 10th place (1904-05). Satterthwaite was top scorer with 11 goals in 30 games.

According to William Pickford, the journalist, Bobby Templeton played the best football of his career for Arsenal. In his book, Association Football and the Men Who Made It (1905) he wrote: "Templeton is afflicted with a large measure of the eccentricity of genius. He is a man of moods. When the afflatus is upon him he is a winged horse to whom a spur is useless, and whom a curb cannot hold. It is then that the watching multitude is aflame with mingled surprise and admiration - surprise at the wondrous versatility of the man, admiration at the grace and beauty of his movements."

Arsenal finished in 12th place in the 1905-06 season. The club also had a good FA Cup run that season beating Watford (3-0), Sunderland (5-0), Manchester United (3-2) before losing to Newcastle United 2-0 in the semi-final with Jimmy Howie and Colin Veitch getting the goals.

Arsenal finished in 7th place in the 1906-07 season. Charlie Satterthwaite was top scorer with 17 goals. Once again they had a good cup run beating Bristol City (2-1), Bristol Rovers (1-0) and Barnsley (2-1) before losing to Sheffield Wednesday 3-1 in the semi-final.

During this period Arsenal had a very impressive forward line that included Bert Freeman, Charlie Satterthwaite, Tim Coleman, Bobby Templeton and Billy Garbutt. The defence was also very good with players such as Jimmy Ashcroft, Andy Ducat, Roderick McEachrane, Jimmy Sharp and Percy Sands in the team. However, Arsenal encountered serious financial problems at this time and within 12 months the club sold Freeman, Coleman, Sharp, Ashcroft and Garbutt. Ducat and Templeton followed soon afterwards.

In April 1908 Bert Freeman was allowed to join Everton. Tony Matthews argues in Arsenal Who's Who that this was "one of the great transfer blunders of those early years." In his first season with his new club he scored 38 goals which made him the league's top scorer. Freeman scored an amazing 61 goals in 86 games for Everton.

Charlie Buchan was another great player they allowed to go. When he was aged 17 years old Buchan was approached by Arsenal and asked to play for the reserves against Croydon Common. Arsenal won 3-1 and Buchan scored one of the goals. Buchan played in three more games and trained twice a week with the team. However, when he provided a bill of 11 shillings for his travel costs, the club refused to reimburse him. As a result, Buchan refused to play anymore games for the club.

Henry Norris, was the chairman of Arsenal at this time. He had made his fortune based on property development in south-west London. Leslie Knighton who worked under Norris later commented: "I have never met his equal for logic, invective and ruthlessness against all who opposed him. When I disagreed with him at board meetings and had to stand up for what I knew was best for the club, he used to flay me with words until I was reduced to fuming, helpless silence."

In August 1910 Alf Common signed for Woolwich Arsenal for a fee of £250. He was now 30 years old and past his best. Five years previously, Middlesbrough had paid Sunderland, the record breaking transfer fee of £1,000 for this outstanding goalscorer. The previous season Arsenal had finished in 18th place and only just survived being relegated to the Second Division. With Common in the side, Arsenal finished 10th in the next two seasons. During this period he scored 23 goals for the club. However, he was less successful in the first-half of the 1912-13 season and was sold to Preston North End for £250.

Leigh Roose joined Arsenal as a player-coach in December, 1911. For many years Roose had been considered the best goalkeeper in Britain. Arsenal's young goalkeeper, Harold Crawford, told Athletic News: "Leigh Roose stands head and shoulders above all others when it comes to goalkeeping and has done so for many years. If you can't learn from him, you can't learn from anyone. He's a master." On 23rd March, 1912, he played against his old team Sunderland at Roker Park. He was in outstanding form and made a series of great saves. At the end of the game he threw his jersey into the crowd and spent over 20 minutes walking around the perimeter of the pitch shaking hands and talking with spectators. A couple of weeks later, he retired from the game. Over a ten year period he had played 285 games in the First Division of the Football League.

In the 1912-13 season Arsenal finished bottom of the First Division and were relegated. Henry Norris believed that the club had to move to an area which was highly populated and had a good transport network. Eventually he paid £20,000 for a 21 year lease on land owned by the Church of England at Highbury. One of the great advantages of the site was its proximity to Gillespie Road underground station. Tottenham Hotspur, Leyton Orient and Chelsea all complained to the League Management Committee about the proposed new stadium as they feared it would reduce the number of people attending their games. However, after a meeting in March 1913, the Football League announced "that under the rules and practice of the League we have no right to interfere."

It cost Henry Norris £80,000 to build Highbury Stadium. Norris desperately needed Arsenal to get back into the First Division if he was to get a profit out of his investment. However, in the 1913-14 season Arsenal finished in 3rd place and failed to go up because of a worse goal average than Bradford Park Avenue.

The outbreak of the First World War made it impossible for Arsenal to win promotion over the next four years. The players either joined the armed services or worked in the munition factories. James Maxwell, Woolwich Arsenal's outside-right in the 1908-09 season, served with the Royal Scots in France until being killed on 27th September 1915. Spencer Bassett, who had played for Arsenal between 1906-1910, was killed on the Western Front in 11th April 1917.

On the outbreak of the war Leigh Roose, who played for the club in the 1911-12 season, immediately joined the Royal Army Medical Corps. His father, Richmond Roose was a pacifist who was strongly opposed to his son becoming involved in the conflict. Roose was sent to France and worked at a hospital in Rouen. His job was to treat injured soldiers from the Western Front before arranging their transport back to Britain.

In April 1915 Leigh Roose was transferred to the Evacuation Hospital at Gallipoli. After spending several months treating the wounded, Roose returned to London. Roose now joined the 9th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers as a private. In 1916 he was sent to Western Front and had his first experience of trench warfare close to the village of Dainville. In August he won the Military Medal for bravery while fighting at the Battle of the Somme. The citation explained how he threw "bombs until his arms gave out, and then, joining the covering party, used his rifle with great effect".

While serving on the front-line Roose suffered from trench foot, a fungal infection brought on by prolonged exposure to damp, cold and unhygienic conditions.

Leigh Roose was killed on 7th October 1916 during an attack on the German trenches at Gueudecourt. Gordon Hoare, who before the war had represented England as an amateur footballer, saw Roose running towards the enemy at full speed in No Man's Land, while firing his gun. Soon afterwards, another soldier saw Roose lying in a bomb crater. His body was never recovered.

Arsenal did play friendly games during the war and on 19th February 1916 a match was arranged with Reading. The England international, Bob Benson, worked in a munitions factory in London during the war. On 19th February 1916, Benson went to watch Arsenal play Reading. Arsenal's right-back, Joe Shaw, could not get away from his job and so Benson, who had not played for a year, agreed to take his place in the team. Clearly unfit, Benson was forced to retire from the field feeling unwell. He tragically died in the dressing-room in the arms of the Arsenal trainer, George Hardy. It was later discovered that he had died of a burst blood vessel. Benson was buried in his Arsenal shirt.

At the end of the First World War it was decided to increase the First Division from 20 to 22 clubs. One solution to the problem was to allow the relegated clubs in the 1914-15 season, Chelsea and Tottenham Hotspur, to remain in the First Division. However, Henry Norris, the Arsenal chairman, disputed this idea. Norris, who had just been elected to the House of Commons as a Conservative MP, argued that a great deal of match-fixing had gone on in the 1914-15 season and that league positions should be disregarded. The reason for this was that Arsenal had finished in 5th place in the Second Division in the 1914-15 season and therefore had no grounds for being elected to the First Division.

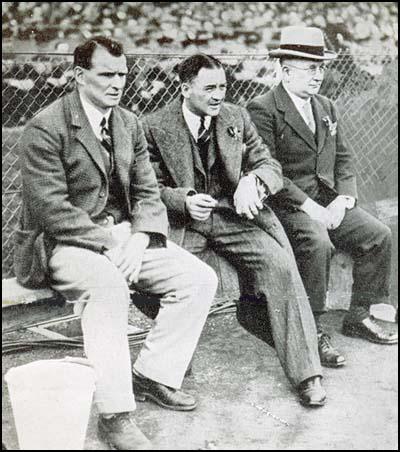

Joe Irvine, Henry Norris and Leslie Knighton.

It was decided to give Chelsea one of the vacant places in the First Division. However, Norris persuaded the league chairman to vote on the other club to join them. Arsenal won the ballot with 18 votes. Spurs only got 8 whereas Barnsley, who finished 3rd in the Second Division in the 1914-15 season, received 5 votes. Many people were of the opinion that Norris had bribed his fellow chairmen in order to win the election.

In June 1919 Henry Norris appointed Leslie Knighton as manager of Arsenal. However, Knighton was just a figurehead and Norris took all the major decisions. For example, he told Knighton he could not spend more than £1,000 on anyone player. Nor was he allowed to sign anyone under 5 foot 8 inches or 11 stone. Knighton was also ordered to abandon the Arsenal scouting system.

Understandably, the club enjoyed no success under Knighton's managership. Although he did manage to buy some excellent players such as Alf Baker, Bob John and Jimmy Brain. He also signed Tom Whittaker who he converted from a centre-forward to left-half and Dan Lewis, a goalkeeper from Clapton Orient. Arsenal's best league position was 9th in 1921. In the FA Cup Arsenal only got beyond the second round once, in 1922, when they lost to Preston North End in the quarter finals after a replay.

Henry Norris sacked Leslie Knighton at the end of the 1924-25 season. Norris advertised the job in the Athletic News on 11th May 1925. It read: "Arsenal Football Club is open to receive applications for the position of Team Manager. He must be experienced and possess the highest qualifications for the post, both as to the ability and personal character. gentlemen whose sole ability to build up a good side depends on the payment of heavy and exorbitant transfer fees need not apply."

In the summer of 1925 Henry Norris offered Herbert Chapman, the highly successful manager of Huddersfield Town, a salary of £2,000 a year if he agreed to manage Arsenal. When one considers that football stars were only paid £300 a year, this was an attractive proposition. However, Harry Norris had a reputation for dictatorial behaviour. Also, whereas Huddersfield had won the championship for the successive season, Arsenal had narrowly escaped relegation by finishing in 20th position.

After lengthy negotiations Henry Norris agreed that Herbert Chapman would be allowed complete control over the team and that money would be made available to strengthen the squad. Chapman's first concern was to buy a "general" like Clem Stephenson, who had played such a vital role in the success of Huddersfield Town. His choice was Charlie Buchan, who had scored 209 goals in 380 games for Sunderland. Bob Kyle, the Sunderland manager, explained to Buchan the complex arrangements of the deal: "We pay Sunderland cash down £2,000, and then we hand over £100 to them for every goal you score during your first season with Arsenal."

In October 1925 Arsenal lost 7-0 to Newcastle United. As with his previous clubs, Herbert Chapman had a weekly meeting with his players. As a result of this discussion, Chapman changed the way the side played. At that time most teams played in the 2-3-5 formation. This system dominated football until 1925 when the Football Association decided to change the offside rule. The change reduced the number of opposition players that an attacker needed between himself and the goal-line from three to two. This had a profound impact on the way football was played. In the season before the introduction of this new offside law, 4,700 goals were scored in the Football League. During the next season the number went to 6,373.

At the meeting Charlie Buchan suggested to Herbert Chapman that the team should exploit this change in the law to create a new playing formation. According to Tom Whittaker, Buchan suggested: "Why not have a defensive centre-half, or third full-back, to block the gap down the middle?" At that time the centre-half played a much more attacking role. Buchan argued that the club should now have a more defence-minded player in that position and that he, rather than the two full-backs, should take responsibility for the offside trap. Chapman agreed with this idea and in fact he had already experimented with this idea at Huddersfield Town before the rule change. Tom Wilson, the centre-half, played as a member of a three-man back-line.

It was decided that the full-backs should play just in front of the centre-half whereas one of the inside-forwards should act as a link between attack and defence. The formation was therefore changed from 2-3-5 to 3-3-4. It was also known as the "WM" formation.

Jack Butler was initially selected to play the centre-half role. However, he was soon replaced by Herbert Roberts, who was the reserve wing-half at the time. Cliff Bastin later pointed out that: "As an all-round player he may have had his failings, but he fitted in perfectly with the Arsenal scheme of things." Roberts became known as the "stopper" or the "policeman" and rarely moved upfield. Tom Whittaker added: "Roberts's genius came from the fact that he was intelligent, and even more important, that he did what he was told."

Jeff Harris argues in his book, Arsenal Who's Who: "Off the field Herbie was a gentleman, shy and unassuming, on the field he was known as Policeman Roberts whose main aim was to blot out and stop the opponents' centre-forward and these policies made him into one of the most unpopular players the length and breadth of the country. Whether it be at Portsmouth or Sunderland the unruffled red haired Roberts was abused and barracked when ever he played away."

Charlie Buchan wanted to play the roving inside-forward role. However, Herbert Chapman disagreed and selected veteran Andy Neil to become the link man in the system. At the time Neil was playing in the third-team. Chapman argued that Neil was "as slow as a funeral but has ball control" and could pass the ball accurately. Later this role went to Jimmy Ramsey and Billy Blyth.

At the time it was common for teams to attack via the wing. When he was manager of Huddersfield Town Chapman had argued that this "senseless policy of running along the lines and centring just in front of the goalmouth, where the odds are nine to one on the defenders". Chapman developed the strategy of "inside passing" as he considered this to be "more deadly, if less spectacular, method." However, it took him time to buy the players who could play this way.

One of Herbert Chapman's first signings was Bill Harper, who cost £4,000 from Hibernian. He replaced Dan Lewis as Arsenal's first-choice goalkeeper.

In the 1925-26 season Arsenal finished in second-place to Chapman's old club, Huddersfield Town. Top scorer was Jimmy Brain who established a new club record with 33 goals. This included four hat-tricks against Everton (twice), Cardiff City and Bury. Brain's partner, Charlie Buchan, scored 21 goals that season which brought the amount paid by Arsenal to Sunderland to £4,100.

Bill Harper played in the first 20 games of the 1926-27 season until Tottenham Hotspur beat them 4-2 at Highbury. Lewis now returned to the first-team. His form was so good that he won the first of his three caps for Wales that season.

In February 1926 Herbert Chapman purchased Joe Hulme from Blackburn Rovers for a fee of £3,500. Hulme was considered the fastest winger in England. As Jeff Harris has pointed out in his book, Arsenal Who's Who: "By the end of the first season Hulme's startling pace had become his trade mark, his main trick being to push the ball past the opposing full-back then tear past him as if he never existed."

Henry Norris refused to allow Herbert Chapman to spend too much money to strengthen his team and in the 1926-27 season Arsenal finished in 11th position. However, they did enjoy a good run in the FA Cup. They beat Port Vale (0-1), Liverpool (2-0), Wolverhampton Wanderers (1-0) and Southampton (2-1) to reach the final at Wembley against Cardiff City.

With 17 minutes to go, Hughie Ferguson hit a shot at the Arsenal goal that struck Tom Parker and the ball slowly rolled towards Dan Lewis, the goalkeeper. As Lewis later explained: "I got down to it and stopped it. I can usually pick up a ball with one hand, but as I was laying over the ball. I had to use both hands to pick it up, and already a Cardiff forward was rushing down on me. The ball was very greasy. When it touched Parker it had evidently acquired a tremendous spin, and for a second it must have been spinning beneath me. At my first touch it shot away over my arm."

Ernie Curtis, Cardiff's left-winger, later commented: "I was in line with the edge of the penalty area on the right when Hughie Ferguson hit the shot which Arsenal's goalie had crouched down for a little early. The ball spun as it travelled towards him, having taken a slight deflection so he was now slightly out of line with it. Len Davies was following the shot in and I think Dan must have had one eye on him. The result was that he didn't take it cleanly and it squirmed under him and over the line. Len jumped over him and into the net, but never actually touched it."

In the words of Charlie Buchan: "He (Lewis) gathered the ball in his arms. As he rose, his knee hit the ball and sent it out of his grasp. In trying to retrieve it, Lewis only knocked it further towards the goal. The ball, with Len Davies following up, trickled slowly but inexorably over the goal-line with hardly enough strength to reach the net."

Soon afterwards, Arsenal had a great chance to draw level. As Charlie Buchan later explained: "Outside-left Sid Hoar sent across a long, high centre. Tom Farquharson, Cardiff goalkeeper, rushed out to meet the danger. The ball dropped just beside the penalty spot and bounced high above his outstretched fingers. Jimmy Brain and I rushed forward together to head the ball into the empty goal. At the last moment Jimmy left it to me. I unfortunately left it to him. Between us, we missed the golden opportunity of the game." Arsenal had no more chances after that and therefore Cardiff City won the game 1-0.

After the game Dan Lewis was so upset that his mistake had cost Arsenal the FA Cup that he threw away his loser's medal. It was retrieved by Bob John who suggested that the team would win him a winning medal the following season. Herbert Chapman believed that Lewis was the best goalkeeper at the club and he retained his place in the team the following season.

Tom Whittaker had been a member of Arsenal playing staff until he suffered a serious injury in 1925. He was told he would be off a long time and so he did a course in anatomy, massage and electrical treatment of injuries. When he returned to Highbury he was unable to train and therefore he helped in the treatment room. Later he became assistant trainer to George Hardy.

On 2nd February, 1927, Arsenal played in a 4th round FA Cup tie against Port Vale. According to Tom Whittaker: "Arsenal were pressing hard, but things were not going just right and old George Hardy's eyes spotted something he felt could be corrected to help the attack. During the next lull in the game he hopped to the touchline, and cupping his hands, yelled out that one of the forwards was to play a little farther upfield." Chapman was furious and sent Hardy to the dressing-room.

On the following Monday morning Herbert Chapman summonded Tom Whittaker to his office and told him that he was now the first-team trainer. Chapman added: "I am going to make this the greatest club ground in the world, and I am going to make you the greatest trainer in the game."

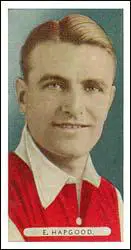

In October 1927, Herbert Chapman signed Eddie Hapgood, a 19 year old milkman, who was playing for non-league Kettering Town for a fee of £750. In his autobiography Hapgood describes his first meeting with Chapman: "Well, young man, do you smoke or drink?" Rather startled, I said, "No, sir." "Good," he answered. "Would you like to sign for Arsenal"

Eddie Hapgood only weighed 9 stones 6 pounds at the time and as Tom Whittaker, the Arsenal trainer, pointed out: "Hapgood used to cause a lot of worry by frequently being knocked out when heading the ball." Whittaker later recalled: "All sorts of reasons were propounded as to why this should happen, but eventually I spotted the cause. Eddie was too light, and we had to build him up. At that time he was a vegetarian, but I decided he should eat meat."

Bob Wall, Chapman's administrative assistant, wrote in his autobiography, Arsenal from the Heart: "He (Hapgood) played his football in a calm, authoritative way and he would analyse a game in the same quiet, clear-cut manner. Eddie set Arsenal players the highest possible example in technical skill and personal behaviour."

Hapgood made his debut against Birmingham City on 19th November 1927. It was not long before he was the club's regular left-back. As Jeff Harris pointed out in his book, Arsenal Who's Who: "Hapgood's many splendid attributes included, being technically exceptional, he showed shrewd anticipation and he was elegant, polished, unruffled and calm." Tom Whittaker added that: "Hapgood was an extraordinary youngster. Confident beyond his years, some people found him insufferable at times. But it was the supreme confidence in his own ability which made him such a great player."

In 1927 the Daily Mail reported that Henry Norris had made under-the-counter payments to Sunderland's Charlie Buchan as an incentive for him to join Arsenal in 1925. The Football Association began an investigation of Norris and discovered that he had used Arsenal's expense accounts for personal use, and had obtained the proceeds of £125 from the sale of the team bus. Norris sued the newspaper and the FA for libel, but in February 1929 he lost his case. The FA now banned Norris from football for life.

In August 1928 the Arsenal team wore numbers on their backs. Herbert Chapman believed that these numbers would speed up moves by helping players identify each other more quickly. The Football League disagreed with this innovation and immediately banned the club from doing this again. Chapman had to content himself by placing numbers on the back of his reserve team.

Chapman became frustrated by the conservatism of the Football Association and the Football League. In an article in the Sunday Express he stated: "I appeal to the authorities to release the brake which they seem to delight in jamming on new ideas... as if wisdom is only to be found in the council chamber... I am impatient and intolerant of much that seems to me to be merely negative, if not actually destructive, legislation."

Chapman added: "We owe it to the public that our games should be controlled with all the exactness that is possible." He therefore suggested the introduction of goal judges. He was also in favour of playing games at night. Chapman arranged for floodlights to be built into the West Stand but the Football Association refused permission for the club to use them for official matches.

Bob Wall later wrote: "Chapman thought deeply about an infinite variety of subjects associated with the game. He possessed the gift of seeing ahead of his time. He was able to visualize how soccer could benefit from adopting ideas which, in their infancy, seemed to most other people to be merely the outpourings of an eccentric mind."

Chapman was also in favour of bonding sessions with the players. He was probably the first manager to take his players on a golfing holiday. The team regularly went to Brighton where they played golf at the Dyke Club. As Stephen Studd pointed out in Herbert Chapman: Football Emperor (1981): "He (Chapman) set great store by what he regarded as the dignity of the athlete, treating his players as human beings instead of mere paid servants, which was how most other players were regarded elsewhere."

Samuel Hill-Wood became the new chairman of Arsenal. He had made his fortune from the cotton industry in Derbyshire and had previously owned Glossop North End. Freed from the restraints placed on him by the former chairman, Herbert Chapman began to buy the best players available. In May 1928, he paid a four-figure sum for Charlie Jones, who had developed a great reputation playing for Wales.

In October, 1928, he decided to pay a transfer fee of over £10,000 for David Jack. Sir Charles Clegg, president of the Football Association, immediately issued a statement claiming that no player in the world was worth that amount of money. Others thought that at 29 years old, Jack was past his best. However, Chapman later commented that the buying of Jack was "one of the best bargains I ever made".

In May 1929 Herbert Chapman signed the 17-year-old Cliff Bastin from Exeter City for £2,000. This was considered to be a huge sum to pay for a teenager who had only played in seventeen league games. Chapman had spotted Bastin in a game against Watford. Bastin did not initially want to leave Devon but was persuaded by Chapman's manner: "There was an aura of greatness about Chapman. I was impressed with him straight away. He possessed a cheery self-confidence, which communicated itself to those around him. This power of inspiration and the remarkable gift of foresight, which never seemed to desert him, were his greatest attributes."

The following month Chapman purchased Alex James from Preston North End for a fee of £8,750. At the time, the Football League operated a maximum wage of £8 a week. However, other clubs like Arsenal had found ways around this problem. Chapman arranged for James to obtain a £250-a-year "sports demonstrator" job at Selfridges. It was also agreed that James would be paid for a weekly "ghosted" article for a London evening newspaper.

Alex James had been a goalscoring inside-forward at Preston North End. However, Chapman wanted him to plat the role of link man in his system. James found it difficult to adapt to this role and Arsenal started the 1929-30 season badly. In a cup-tie against Chelsea Chapman dropped James from the team. Arsenal won the game and James was not recalled until he had convinced Chapman that he was willing to play the link man role.

Chapman's team-talk took place on Friday morning. His administrative assistant Bob Wall remarked that he always told players: "Never mind what the other team does - this is what you are going to do." Chapman had a magnetic table marked out as a football field, with little toy players that could be moved around on it. Every player was encouraged to give his own views on the game taking place the following day. By the end of the meeting every player was fully aware of the role they were to play in the match. As the Daily Mail pointed out at the time: "Breaking down old traditions, he was the first club manager who set out methodically to organize the winning of matches."

Frank Cole of the Daily Telegraph, wrote: "If you sat near him (Chapman) at a big match... you realized the intense earnestness of the man. His face would go ashen grey as he lived every moment of the play. And when things were going against his men he seemed to be suffering mental agonies. I have never seen such concentration."

Herbert Chapman gradually adapted the "WM" formation that he had introduced when he first came to the club. Herbert Roberts was the centre-half who stayed in the penalty area to break down opposing attacks. Chapman used his full-backs, Eddie Hapgood and Tom Parker, to mark the wingers. This job had previously been done by the wing-halves, who now concentrated on looking after the inside-forwards. Bob John and Alf Baker were the men he used in these positions. Dan Lewis was the goalkeeper in what became known as "defence-in-depth". The young George Male was often used if any of the full-backs or wing-halves were injured.

Pulling the centre-half back left a gap in midfield and so Chapman needed a link man to pick up the ball from defence and to pass it on quickly to the attackers. This was the job of Alex James, who had the ability to make accurate long low passes to goalscoring forwards like David Jack, Jimmy Brain, Joe Hulme, Charlie Jones, Cliff Bastin and Jack Lambert. Chapman told the other forwards to go fast, like "flying columns" and if possible to make for goal direct.

Herbert Chapman pointed out: "Although I do not suggest that the Arsenal team go on the defensive even for tactical purposes, I think it may be said that some of their best scoring chances have come when they have been driven back and then have broken away to strike suddenly and swiftly." He added "the quicker you get to your opponent's goal the less obstacles you find".

Chapman also rarely made changes to the team. Even when individual players were in poor form he was reluctant to drop them. According to Chapman it was a matter of confidence and he saw it as his job to build up self-belief in his players. That is why he always criticised supporters if they barracked one of his players. "When they (team changes) are necessary I try to arrange that they cause as little disturbance as possible." Drastic changes only unsettled the players and if the side was not playing well, "the moderate course is always the best".

Jack Lambert was one of the players who was often barracked by the Highbury crowd. Herbert Chapman was furious and proposed that barrackers should be thrown out of the ground if they did not respond to an appeal for fairness over the loud-speaker." Chapman later admitted that Arsenal crowd destroyed the confidence of one young player. The 20 year-old player told Chapman: "I'm no use to anyone in football and I had better get out. The crowd are always getting at me... I hope I shall never kick a ball again." Chapman eventually allowed the young man to leave the club "though it meant sacrificing a player who, I was convinced, had exceptional possibilities of development".

Success was not immediate and Arsenal finished in 14th place in the 1929-30 season. They did much better in the FA Cup. Arsenal beat Birmingham City (1-0), Middlesbrough (2-0), West Ham United (3-0) and Hull City (1-0) to reach the final against Chapman's old club, Huddersfield Town.

Dan Lewis had played in six of the seven ties on the way to the final. However, Herbert Chapman took the controversial decision of dropping Lewis, the man who had cost Arsenal victory in the 1927 FA Cup Final, from the team. At the age of 18 years and 43 days, Cliff Bastin was the youngest player to appear in a final.

Eddie Hapgood later described the role that Alex James played in the 2-0 victory. "Alex was fouled somewhere near the penalty area, and, almost before the ball had stopped rolling, had taken the free-kick. He sent a short pass to Cliff Bastin, moved into position to take a perfect return, and banged the ball into the Huddersfield net for the all-important first goal. Tom Crew told me that James made a silent appeal for permission to take the kick, and he waved him on. It was one of the smartest moves ever made in a big match and it gave us the Cup. I contend that it was fair tactics; for if Alex had waited a few seconds for the whistle, the Huddersfield defence would have been in position, and the advantage of the free-kick would have been lost." Jack Lambert got the second goal late in the second half, also from a move started by Alex James.

Dan Lewis was devastated by Chapman's decision and asked for a transfer. He was sold to Gillingham and Chapman resigned Bill Harper, who had been playing in the United States for three years.

Arsenal won their first five matches in the 1930-31 season and did not lose until the tenth game. Aston Villa took a narrow lead but in November, 1930, Arsenal beat them 5-2 at Highbury with Cliff Bastin and David Jack scoring twice and Jack Lambert once. Sheffield Wednesday now went on a good run and for a while had a narrow lead over Arsenal. However, a 2-0 win over Wednesday in March took them to the top of the league. This was followed by victories over Grimsby Town (9-1) and Leicester City (7-2).

When Arsenal beat Liverpool 3-1 at Highbury they became the first southern club to win the First Division title. The Gunners won 28 games and lost only four and obtained 66 points, six more than the previous best total and seven more than their nearest rivals, Aston Villa. That season Arsenal won a percentage of 78.57 points available to them. This had been bettered twice before by Preston North End (1888-89) with 90.9 and Sunderland (1891-92) with 80.7.

Jack Lambert was top-scorer with 38 goals. This included seven hat-tricks against Middlesbrough (home and away), Grimsby Town, Birmingham City, Bolton Wanderers, Leicester City and Sunderland. The veteran David Jack scored 31 goals in 35 games. Other important players in the team included Alex James, Cliff Bastin, Joe Hulme, Eddie Hapgood, Bob John, Jimmy Brain, Tom Parker, Bill Harper, Herbert Roberts, Alf Baker and George Male.

Cliff Bastin later recalled: "This Arsenal team of 1930-31 was the finest eleven I ever played in. And, without hesitation, I include in that generalization international teams as well. Never before had there been such a team put out by any club."

Herbert Chapman was always preparing for the future. A lot of energy went into producing a good reserve side. As Bernard Joy pointed out: "Chapman had intended to set up a strong second string when he came to Highbury and more convincing proof that he had succeeded when was the reserves came into the senior team." In the 1930-31 season the Arsenal reserve side won the Combination league title for the fifth year running.

Frank Moss was playing in the reserves of Second Division side, Oldham Athletic, when Herbert Chapman, saw his potential and bought him for £3,000. He made his debut against Chelsea on 21st November 1931. He remained the first-team goalkeeper for the rest of the season.

Arsenal began the season badly. West Bromwich Albion won at Highbury in the opening game and victory did not come until the fifth match, at home to Sunderland. Arsenal's main problem was a lack of goals from Jack Lambert who was suffering from an ankle injury. However, Lambert recovered his goalscoring touch and Arsenal went on a good run and gradually began to catch the leaders, Everton.

Arsenal also did well in the FA Cup. They beat Plymouth Argyle (4-2), Portsmouth (2-0), Huddersfield Town (1-0), and Manchester City (1-0) to reach the final. Arsenal's league form was also good and after the FA semi-final they were only three points behind Everton, with a game in hand. This was followed by victories over Newcastle United and Derby County and it seemed that Arsenal might win the cup and league double.

The next game was against West Ham United at Upton Park. After two minutes Jim Barrett went for a loose ball with Alex James. According to Bernard Joy: "James chased after it, both went awkwardly into the tackle and as James slipped, down came the full weight of Barrett's fifteen stone on to his outstretched leg." James had suffered serious ligament damage and was unable to play for the rest of the season. Arsenal missed their playmaker and won only one more league game and Everton won the title by two points.

Arsenal played Newcastle United in the FA Cup Final on 23rd April, 1932. The Arsenal team that day was: Frank Moss, Tom Parker, Eddie Hapgood, Charlie Jones, Herbert Roberts, George Male, Joe Hulme, David Jack, Jack Lambert, Cliff Bastin and Bob John. Arsenal scored first, eleven minutes after the start, when John headed in a centre by Hulme.

Just before half-time Jimmy Richardson chased what appeared to be a lost cause, when David Davidson sent a long ball up the right wing. When the ball appeared to bounce over the line, the Arsenal defence instictively relaxed. Richardson managed to hook the ball into the middle and Jack Allen was able to head home. Despite the protests, the referee W. P. Harper, awarded the goal. David Jack missed an easy chance midway through the second-half and soon afterwards Allen scored again to win the game for Newcastle United 2-1.

At the beginning of the 1932-33 season Herbert Chapman changed Arsenal's kit. He replaced the lace-up jersey with a shirt with buttons at the neck and a turn-over collar. He also decided that the sleeves should now be white instead of red. The colour of the socks was altered to a more distinctive blue and white so that the players could recognize their colleagues more easily without looking up.

Arsenal was in great form in the 1932-33 season. They only lost two matches against West Bromwich Albion and Aston Villa in their first 18 games. A 9-2 win over Sheffield United gave the club a six-point lead at Christmas.

Arsenal played Walsall of the Third Division North in the FA Cup on 14th January 1933. Injuries and illness robbed Arsenal of several key players including Eddie Hapgood, Joe Hulme, Jack Lambert and Bob John. Four inexperienced reserves were drafted into the side. They all performed badly and so did the regular members, with David Jack missing several opportunities to score. The tackling of the Walsall players, especially on Alex James and Cliff Bastin, also caused the team serious problems. As Bernard Joy pointed out: "They (Walsall) were aided by the narrow ground which was made more cramped by the encroachment of spectators up to the touchlines."

Fifteen minutes after the interval, Gilbert Allsop headed in from a corner. Soon afterwards, Tommy Black, who was deputising for Eddie Hapgood, gave away a penalty with a blatant foul on Bill Sheppard. Walsall scored from the spot and managed to hold out for a 2-0 win. It was the greatest giant-killing result in FA Cup history.

Herbert Chapman was furious with Tommy Black because he had made several bad tackles on Bill Sheppard before giving away the penalty. Chapman set high standards of behaviour on the field and Black's behaviour was unforgivable. He was banned from Highbury and soon afterwards he was transferred to Plymouth Argyle.

Arsenal recovered quickly from the defeat in the FA Cup and were unbeaten in the league until March. This included a 8-0 win over Blackburn Rovers. By the end of the season Arsenal was four points in front of Aston Villa.

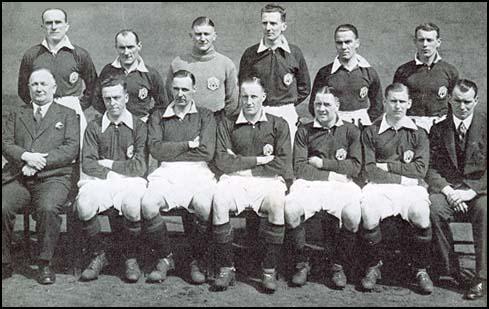

Frank Moss, Herbie Roberts, Bob John and Tommy Black. Seated: Herbert Chapman,

Joe Hulme, David Jack, Jack Lambert, Alex James, Cliff Bastin and Tom Whittaker.

Cliff Bastin, the team's left-winger, was top scorer with 33 goals. This was the highest total ever scored by a winger in a league season. Joe Hulme, the outside right, contributed 20 goals. This illustrates the effectiveness of Chapman's counter-attacking strategy. As the authors of The Official Illustrated History of Arsenal have pointed out: "In 1932-33 Bastin and Hulme scored 53 goals between them, perfect evidence that Arsenal did play the game very differently from their contemporaries, who tended to continue to rely on the wingers making goals for the centre-forward, rather than scoring themselves. By playing the wingers this way, Chapman was able to have one more man in midfield, and thus control the supply of the ball, primarily through Alex James."

Jeff Harris argues in his book, Arsenal Who's Who: "The reason that Bastin was so deadly was that unlike any other winger, he stood at least ten yards in from the touch line so that his alert football brain could thrive on the brilliance of James threading through defence splitting passes with his lethal finishing completing the job."

Matt Busby was playing for Manchester City at the time. He later recalled: "Alex James was the great creator from the middle. From an Arsenal rearguard action the ball would, seemingly inevitably, reach Alex. He would feint and leave two or three opponents sprawling or plodding in his wake before he released the ball, unerringly, to either the flying Joe Hulme, who would not even have to pause in his flight, or the absolutely devastating Cliff Bastin, who would take a couple of strides and whip the ball into the net. The number of goals created from rearguard beginnings by Alex James were the most significant factor in Arsenal's greatness."

In March 1933, Herbert Chapman paid £4,500 for Ray Bowden. He was brought in to replace David Jack who was nearing the end of his career. The 1934-35 season started well with an 8-1 crushing of Liverpool. The first four home games produced 21 goals. The away form was poor but Arsenal built up an early lead in the First Division.

On 1st January 1934 Herbert Chapman went to watch Notts County play Bury as he was interested on one of their young players. The following day he attended the game between Sheffield Wednesday and Birmingham City. Wednesday were the visitors at Highbury on the following Saturday and Chapman considered them to be Arsenal's main rivals for the league championship. He developed a cold but insisted on watching Arsenal's third team play on the Wednesday. The following day he was forced to take to his bed and died of pneumonia on Saturday morning. Chapman was buried at St Mary's in Hendon on 10th January 1934. David Jack, Eddie Hapgood, Joe Hulme, Jack Lambert, Cliff Bastin and Alex James were the six pallbearers.

Herbert Chapman had been accused of buying success at Arsenal and they became known as the Bank of England club. However, between 1925 and 1934 Chapman had spent £101,000 in fees and received £40,000 for those he sold. A yearly average cost of £7,000. This was easily made up for in increased revenue from gate receipts. For example, in his final year as manager, the club made a profit of £35,000.

George Allison was appointed as the new manager. Allison was a radio journalist who was also the club's managing director. However, he had no experience of football management. At the time of Chapman's death Arsenal were top of the table and Tom Whittaker and Joe Shaw were allowed to run the team until the end of the season. Bob Wall claimed that "Allison was a complete contrast to Chapman... He never claimed to possess a deep theoretical knowledge of the game but he listened closely to what people like Tom Whittaker and Alex James had to say. Like Chapman before him, Allison always insisted that, no matter how good a prospective signing might be, he would secure him only if his character was beyond reproach."

Sunderland were Arsenal's main challengers in the 1933-34 season thanks to a forward line that included Raich Carter, Patsy Gallacher, Bob Gurney and Jimmy Connor. In March 1934 Sunderland went a point ahead. However, the Gunners had games in hand and they clinched the league title with a 2-0 victory over Everton. One of the goals was scored by goalkeeper Frank Moss who suffered a dislocated shoulder and was forced to play on the left-wing for the remainder of the game.

In March 1934, George Allison paid £6,500 for Ted Drake who had been scoring a lot of goals for Southampton in the Second Division. Herbert Chapman had tried to buy him the previous year but his offer had been refused. Allison also purchased Jack Crayston for £5,250 in May 1934.

Another important signing was Wilf Copping. In June 1934, George Allison, paid £8,000 for the England international. As one historian has pointed out: "Wilf Copping was the original hard man of English football... with his boxer's nose and build, his unshaven appearance on match days and the bone shaking charges and tackles which were his trademark. Copping, at left half, was liable to unnerve the opposition with just one fixed stare from his craggy face."

Jack Crayston was a great success at Arsenal. He made his debut against Liverpool on 1st September 1934. and scored in the 8-1 victory. According to Jeff Harris, the author of Arsenal Who's Who, Cranston was "full of grace, an excellent ball player, strong in the tackle and brilliant in the air." Crayston also became close friends with Wilf Copping. As Tom Whittaker pointed out in his autobiography, The Arsenal Story: "Although very dissimilar on and off the field, Crayston and Copping were inseparable. They trained together - that was another idea handed on by Chapman; he always insisted that a fast runner should train together with a slower mover, so as to help him increase his pace - and on all journeys were to be seen together, inevitably playing a peculiar form of Chinese whist."

One historian has described Wilf Copping as "the original hard man of English football... with his boxer's nose and build, his unshaven appearance on match days and the bone shaking charges and tackles which were his trademark. Copping, at left half, was liable to unnerve the opposition with just one fixed stare from his craggy face. The harder the going, the more Copping liked it."

Bill Shankly claimed that Copping was a player who "played the man rather than the ball". Tommy Lawton also complained about Copping. While playing for Everton Lawton constantly beat the Arsenal defenders in the air and Copping warned him that he was "jumping too high" and that he would have to be "brought down to my level". As Lawton later recalled: "Sure enough the next time we both went for a cross, I end up on the ground with blood streaming from my nose. Wilf was looking down at me and he said 'Ah told thee, Tom. Tha's jumping too high!' My nose was broken. When Arsenal came to Everton, Copping broke my nose again! He was hard, Wilf. You always had something to remember him by when you played against him."

Wilf Copping, Frank Moss, Ted Drake and Alex James

Jeff Harris argues in his book, Arsenal Who's Who (1995) that Copping "had the legendary reputation of being more than forceful in the tackle... and that he was the first to admit that he was temperamental and fiery his bone-jarring tackles were mainly timed to perfection and fair". Harris adds that proof that Copping was a clean player is the fact that he played in 340 league games and was never cautioned or sent-off during his career.

Ted Drake scored 42 goals in 41 games in the 1934-35 season. This included three hat-tricks against Liverpool, Tottenham Hotspur and Leicester City and four, four-goal hauls, against Birmingham City, Chelsea, Wolves and Middlesbrough. These goals helped Arsenal to win the league championship. Jeff Harris, the author of Arsenal Who's Who argues that "Drake's main attributes were his powerful dashing runs, his great strength combined with terrific speed and a powerful shot. Ted Drake was also brilliant in the air but above all, so unbelievably fearless."

Ted Drake had a particularly good game against Aston Villa on 14th December, 1935. He was suffering from a knee injury but George Allison decided to risk him. By half-time he had scored a hat-trick. Drake scored three more in the first 15 minutes of the second-half. Drake then hit the bar and when he told the referee it had crossed the line, he replied: "Don't be greedy, isn't six enough". In the last minute he converted a cross from Cliff Bastin. Seven goals in an away game was an amazing achievement.

However, a serious knee injury, that needed a cartilage operation, put Ted Drake out of action for ten weeks. Arsenal missed his goals and only finished in 6th place behind Sunderland. Arsenal did much better in the FA Cup that season. Arsenal beat Liverpool (2-0), Newcastle United (3-0), Barnsley (4-1) and Grimsby Town (1-0) to reach the final against Sheffield United. Drake, who was not fully fit, scored the only goal of the game.

Some of Arsenal's key players such as Alex James, Cliff Bastin, Joe Hulme, Bob John and Herbie Roberts were past their best. Ted Drake and Ray Bowden continued to suffer from injuries, whereas Frank Moss was forced to retire from the game. Given these problems Arsenal did well to finish in 3rd place in the 1936-37 season.

in the match against Brentford on 18th April, 1938

Before the start of the 1937-38 season Herbie Roberts, Bob John and Alex James retired from football. Joe Hulme was out with a long-term back injury and Ray Bowden was sold to Newcastle United. However, a new group of younger players such as Reg Lewis, George Swindin, Bernard Joy, Alf Kirchen, Leslie Compton and Dennis Compton managed to get into the first team.

George Allison signed Leslie Jones from Coventry City in November 1937. George Hunt was also bought from Tottenham Hotspur to provide cover for Ted Drake who was still suffering from a knee injury. Cliff Bastin, Eddie Hapgood and George Male were now the only survivors of the team managed by Herbert Chapman.

Wolves were expected to be Arsenal's main rivals in the 1937-38 season. However, it was Brentford who led the table in February. They also beat Arsenal on 18th April, a game in which Ted Drake broke his wrist and suffered a bad head wound. However, it was the only two points they won during a eight game period and gradually dropped out of contention.

On the last day of the season Wolves were away to Sunderland. If Wolves won the game they would be champions, but they drew 1-1. Arsenal beat Bolton Wanderers at Highbury and won their fifth title in eight years. As a result of his many injuries, Ted Drake only played in 28 games but he still ended up the club's top scorer with 17 goals.

George Allison was aware that Arsenal had never been able to replace the retired Alex James and therefore lacked creativity in midfield. In August 1938 Allison decided to buy Bryn Jones of Wolves for the world record fee of £14,000 (£6.9 million in today's money). Politicians were outraged by the money spent on Jones and the subject was debated in the House of Commons.

Bryn Jones scored on his debut against Portsmouth. He also found the net in two of his next three games. However, the goals dried up and he was only to get one more before the end of the season. After Arsenal were beaten at home 2-1 by Derby County, the match reporter from the Derby Evening Telegraph wrote: "Arsenal have a big problem. Spending £14,000 on Bryn Jones has not brought the needed thrust into the attack. The little Welsh inside-left is clearly suffering from too much publicity, and is obviously worried. He is a nippy and quite useful inside-left, but his limitations are marked."

In his first season Bryn Jones scored four goals in 30 league appearances. That year Arsenal finished 5th in the league, eight points behind Wolves who appeared to be doing very well without Jones. As Jeff Harris pointed out in Arsenal Who's Who (1995): "To lay blame on Bryn Jones for the club's lack of success that season was unfair, for in a nutshell, the quiet, modest, self evasive, lonely figure could not cope with the intense pressure of the media spotlight even though his good positional awareness and splendid ball control were there for everyone to behold."

His manager, George Allison, claimed that Bryn Jones needed more time to settle into the team. Cliff Bastin disagreed and in his autobiography he commented: "I thought at the time this was a bad transfer, and subsequent events did nothing to alter my views. I had played against Bryn in club and international matches and had ample opportunity to size him up."

Bernard Joy later wrote: "Do we write Bryn Jones down as a gamble that failed, or would he have been a success eventually? The outbreak of war in September 1939 prevented us from ever finding the complete answer. There were signs before then that, as James had done, he was weathering the bad patch which always seems to follow a change of style from an attacking to a foraging inside-forward... My own view, however, is that Jones's modesty was the barrier to achieving the key role Arsenal had intended for him. He could not regard the spotlight as a challenge to produce his best; all the time it irked him, making him self-conscious and uneasy.” However, the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 brought an end to the debate about the value of Bryn Jones.

Arsenal lost the use of its ground during the war as Highbury was used as an Air Raid Patrol Centre. Most of Arsenal's first-team joined the Royal Air Force. This included Ted Drake, Jack Crayston, Eddie Hapgood, Leslie Jones, Bernard Joy, Alf Kirchen, Laurie Scott and George Swindin. Some of them got jobs as Physical Training instructors and did not see action overseas, whereas others in the team went abroad. This included Dennis Compton (India), Bryn Jones (Italy), Reg Lewis (Germany) and Ted Platt (North Africa). Tom Whittaker, the Arsenal trainer, was promoted to the rank of Squadron Leader and won the MBE for his role in the D-Day operations.

on the outbreak of the Second World War and was killed on 23rd December 1943.

Eight players registered with Arsenal died during the Second World War. Bobby Daniel, a Flight Sergeant Gunner in the RAF, was killed on 23rd December 1943. Other Arsenal players in the RAF who died included Sidney Pugh, Harry Cook and Leslie Lack.

Bill Dean, a goalkeeper who got into the Arsenal team in 1940, told friends: "Well I have fulfilled my life's ambition, I have played for Arsenal." Dean died in action with the Royal Navy in March 1942.

Three Arsenal players who joined the Royal Fusiliers also lost their lives. Hugh Glass was drowned at sea in 1943, Cyril Tooze was killed by a sniper's bullet in Italy on 10th February 1944 and Herbie Roberts, a regular in Arsenal's team that won a hat trick of League Championships between 1932 and 1935, died of erysipelas in June 1944.

In 1945 Tom Whittaker returned to his post as Arsenal's first-team trainer. George Allison resigned in 1947 and Whittaker agreed to become manager of the club. His team, that included George Swindin, Laurie Scott, Bernard Joy, Reg Lewis, Bryn Jones, Alex Forbes, Archie Macaulay, Leslie Compton, Dennis Compton and Ted Platt. Whittaker led the club to the First Division championships in 1947-48.

Reg Lewis was the star of the team. Jeff Harris, the author of Arsenal Who's Who, argues: "His ability and knack of scoring goals were attributed to his fine positional sense when finding space in the box as well as being cool, calm and collected." Lewis had the amazing record of scoring 116 goals in 175 league and cup games. Lewis also scored both goals in Arsenal's 2-0 victory over Liverpool in the 1950 FA Cup Final.

Arsenal finished in 5th (1950-51) and 3rd (1951-52) before winning the First Division championship in 1952-53. However, Reg Lewis was forced into retirement and Arsenal struggled over the next three seasons.

Tom Whittaker died of a heart-attack at the University College Hospital on 24th October 1956. Jack Crayston became the new manager of the club. In his first season Arsenal finished in 5th place. However, the following season Arsenal slipped to 12th place, which was the club's lowest position for 38 years. In May 1958 Crayston resigned as manager.

Lewis returned to Arsenal after the war and scored 29 goals in 28 games in the 1946-47 season. This included a hat-trick against Preston North End and four against Grimsby Town. Jeff Harris, the author of Arsenal Who's Who, argues: "His ability and knack of scoring goals were attributed to his fine positional sense when finding space in the box as well as being cool, calm and collected."

George Swindin was appointed manager of Arsenal in August 1958. He only had moderate success with Arsenal finishing 3rd (1958-59), 13th (1959-60), 11th (1960-61) and 10th (1961-62). Swindin resigned in May 1962.

.Primary Sources

(1) Elijah Watkins, Woolwich Arsenal secretary on the first football pitch the club played on in the match against Eastern Wanderers on 11th December, 1886.

Talk about a football pitch! This one eclipsed any I ever heard of or saw. I could not venture to say what shape it was, but it was bounded by backyards as to about two-thirds of the area, and the other portion was - I was going to say a ditch, but I think an open sewer would be more appropriate. We could not decide who won the game because when the ball was not in the back gardens, it was in the ditch; and that was full of the loveliest material that could possibly be. Well, our fellows did not bring it all away with them, but they looked as though they had been clearing out a mud-shoot when they had done playing. I know, because the attendant at the pub asked me what I was going to give him to clear the muck away.

(2) Arthur Kennedy, The History of Woolwich Arsenal (1905)

In dealing with the history of the Arsenal Club, I may mention that prior to 1886 Association football was practically unknown in the district, rugger holding the sway… In this year, however, a number of enthusiasts for the soccer code, who had migrated from the North and Midlands, conceived the idea of forming an association club, with the result that a meeting was held at the Royal Oak , Woolwich, and the present club saw its inception under the title of the Royal Arsenal Football Club.

(3) Michael Wade, The Arsenal Story: An Official History (1999)

There is a curious similarity between the Arsenal of today and the Royal Arsenal side that preceded it over 100 years ago. Just as the modern team features many players who are making their livings far from the places where they were brought up, so too did that original side. Royal Arsenal was formed in 1886, not by Frenchmen or Italians or Africans, but by men from the Midlands, the North of England and Scotland, all of whom had arrived in London to work.

The very first Arsenal side was, in effect, a works side, formed by people who earned their livings in a vast munitions factory... The first Arsenal football team owed more than its name to this place of work - the vast munitions factory helped to supply a steady flow of players, too. In the latter part of the 19th century, the factory was probably as busy as it ever had been, producing weaponry to bolster the forces of the British Empire and caught up in the escalating arms race that preceded the First World War.

(4) Bernard Joy, Forward Arsenal (1952)

David Danskin was the first captain and Elijah Watkins was secretary. Most of the players were enthusiastic rather than skilful, and had to be instructed by experienced men like Beardsley and Bates. By December, however, enough progress had been made for the club to have its first match, against Eastern Wanderers on a pitch at Millwall. The team was: Beardsley; Danskin, Porteous; Gregory, Bee, Wolfe; Smith, Moy, Whitehead, Morris, Duggan.

It was a far cry from the immaculate turn-out of the present Arsenal side, when the players then took the field. Each man provided his own kit and hardly any two shirts matched. One had a blue and white-barred shirt and shorts of long black trousers, cut down to the correct size. Half the others had white shorts, some of the knickerbocker variety. Two or three wore shin guards, fastened outside the stockings, but the majority had short socks untidily drooping down the leg. Nearly all the boots were ordinary pairs, with bars nailed across the soles....

It was decided to insist on a uniform colour for the shirts. Red was chosen because the former Nottingham Forest men already had shirts of that colour in their possession. That included Beardsley, because goalkeepers did not then wear colours distinctive from those of their colleagues. Funds were low and Beardsley wrote to his old club for help. The result was most generous, a complete set of red shirts and a ball, which was used in the first home match. For many years, the players were known as the "Woolwich Reds" just as Nottingham Forest were called the "Nottingham Reds"...

The first game of the re-formed club was on Plumstead Common against Erith on 8 January 1887. No gate money could be charged and the players had to change in the 'Star' public house nearby. The marking-out of the pitch did not present many problems in those days as there were no lines inside it, and not even the centre-spot was marked. Although crossbars had been legal for three years, a tape was used to denote the height of the goal.

By the end of the season, ten matches had been played: seven were won and only two lost, with a goal analysis of 36-8. The club was thus well and truly launched.

Already the pioneers were congratulating themselves on the happy choice of "Forward" as the club's motto, because with such a good start, further successes seemed assured. But I wonder if their wildest dreams measured up to the actual triumphs of later years. Four of the founders, Danskin, Humble, Beardsley, and Brown lived to see the Cup won in 1930.

(5) Arthur Kennedy, The History of Woolwich Arsenal (1905)

It was in 1891-92 that the momentous decision was arrived at, and I still have vivid recollections of that meeting at the Windsor Castle, when Mr. Humble, one of the then committee, and now the present chairman of the club, moved the resolution which was to eventually revolutionize Association football in the South: "That the Arsenal Club do embrace professionalism." This was carried by an overwhelming majority, and of course, brought down the vials of wrath of the London Football Association on the devoted heads of the Arsenal executive.

(6) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

Always I carried some sort of a ball in my pocket. It did not stay there long. I used to run along the road, using the pavement edge as a colleague.I fear that in these days of heavy traffic, it would be impossible to carry out this sort of practice. But I thought nothing of it. I became so adept at pushing the ball against the pavement and taking the rebound that it did not impede my rate of progress.When I first played for the Polytechnic, my position was left half-back. In one game I happened to score five goals. So I was immediately put into the forward line where I remained for the rest of my playing days.Then I had ambitions of becoming a centre-half, but I was too small for the position. Though I was big enough in after years, nobody seemed to fancy me as a pivot. At any rate, I never played in the position.

Playing regularly for the school team was not enough to satisfy my appetite for the game. Every Saturday afternoon I went down to the Manor Field to see what I could of Arsenal's League and reserve sides.

As my weekly pocket-money was the princely sum of id, I could not pay the 3d admission into the ground. I waited outside, listening to the roars and cheers of the crowd, until about ten minutes before the end when the big, wide gates were thrown open to allow the crowd to trek out.

In I rushed with other soccer-crazy boys to see the finish of the game. It was enough to get a glimpse of my heroes and to watch the way they played the game.Among my favourites then were Bobby Templeton, Scottish international wing forward; big, burly Charlie Satterthwaite, an inside-left with a cannon-ball shot; Tim Coleman, a born humorist and inside-right whom, eventually, I succeeded at Sunderland; Percy Sands, the local schoolmaster centre-half; Roddy McEachrane, a consistently good left half-back and Jimmy Sharp, the youthful looking full-back.

They were the stars upon whom I tried to model my style. And there was no greater pleasure for me than to go, during the training month of August, and in the school holidays, to watch them kicking-in and sometimes retrieve the ball when it went behind the goal.

(7) The Stratford Express (4th November 1914)

At Highbury on Monday, West Ham United and Woolwich Arsenal met in a London Professional Charity Fund match, and the Arsenal succeeded in winning the medals, which were at stake, by 1-0. The game was of the tamest description, easily the most thrilling incident between the referee and Benson early in the second-half. The Arsenal back, in clearing, sent the ball fairly and squarely on to the officials face with such force as to cause him to stagger. After a minute, however, he pluckily resumed his duties. The only goal of the match was scored by Rutherford for the Arsenal about ten minutes after the start.

(8) Tom Whittaker, The Arsenal Story (1957)

I was never a great player. I served the club as well as I knew how during the years following the Great War, held my place in the first team, lost it, and was still proud to play in the London (now "Football") Combination team, or the "stiffs," as it is known in the profession.

During that period, when destiny was shaping my future, I met and knew great players like Jackie Rutherford, whose superstition of entering the field of play last was upset in his final match for the club - v. Blackburn Rovers, Easter Monday, 1922 - before going to Stoke City as team manager. Rutherford was made captain for the day and came out first; Bert White, who was transferred to Blackpool the same week as he scored seven goals against the Athenian League; Billy Milne, the present Arsenal trainer, Fred Pagnam, Billy Blyth, dear old Joe Shaw, who left the club and then came back to take charge of the third team, and became the trusted chief scout at Highbury, Jack Butler, Scottish international Alex Graham, Bob John.

I played in front of Alf Kennedy, the young full-back, who, signed from Crystal Palace, was later to play in

our first Cup Final, against Cardiff in 1927. Other names come thick and fast, Alex Mackie, Joe Toner, Alf Baker, Dr. Paterson, Sid Hoar, A. V. Hutchins, Voysey, Williamson. There were others whose names, but not memories, have been erased by time.

I remember my first sight of the great Charlie Buchan when we went to Roker Park in 1922. I gave a penalty away in the first few minutes by handling the ball, and although I faithfully followed out the instructions to track Charlie all over the field, he had a great game. At the end we walked off together, and big Charlie said: "I am going home to tea when I've changed. Why don't you come? You might as well, you've followed me about all afternoon!"

The playing record of the club ran parallel with my own performances... "nothing to shout about." In season 1920-21 we finished ninth in the League, but for the most part we were struggling. Relegation was a constant danger, but somehow Arsenal managed to scramble clear at the last minute.

(9) Harry Norris, Athletic News (11th May 1925)

Arsenal Football Club is open to receive applications for the position of Team Manager. He must be experienced and possess the highest qualifications for the post, both as to the ability and personal character. gentlemen whose sole ability to build up a good side depends on the payment of heavy and exhorbitant transfer fees need not apply.

(10) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

One day in May 1925, I was serving in my Sunderland shop, when the great Herbert Chapman walked in. A few weeks before, he had left Huddersfield Town to take over the managership of Arsenal.

His first words on seeing me were: "I have come to sign you on for Arsenal."

"Yes,' I replied, thinking he was joking, "shall we go into the back room and sign the forms?"

"I'm serious," was his answer. "I want you to come with me to Highbury."

"Have you spoken to Sunderland about it?" I asked, still thinking it was all part of the joke.

"Oh, yes," said Mr Chapman. "If you don't believe me, ring up Bob Kyle, and he'll tell you."

Still unbelieving, I phoned the Sunderland manager. "Yes," he said, "we have given Arsenal permission to approach you."

"Do you want me to go?" I asked him.

"We are leaving that to you," he said. "Do what you think best for yourself. It's in your hands."

Slowly I put down the receiver. I was almost stunned by what I had heard. It had never crossed my mind that Sunderland would be prepared to part with me so easily.

Mr Chapman just said one word: "Well?"

And all I could say at that moment was: "Give me time to think it over. Come back tomorrow, and I will let you know, one way or the other."

When I went home that evening I talked the matter over with the family. The thing that hurt most was that, after more than fourteen years with Sunderland, my services were so lightly regarded.

Finally I made up my mind. The next morning Mr Chapman again called at the shop. I said to him: "I am prepared to sign for Arsenal, but I shan't do so until the end of July."

"Will you give me your word you'll sign then?" he asked; and when I replied "Yes", we talked of other things. A lot of them concerned the Arsenal team and what I thought about them.

A few weeks later, a Sunderland director, Mr George Short, called on me at the shop. "What's this about your leaving Sunderland?" he asked. When I told him, he replied: "Then I shall resign."

He kept his word. It seemed there were sharply divided opinions about my leaving, but the strange thing is that nobody asked me to change my mind.

The summer went by, and then towards the end of July, Mr Chapman again visited me in Sunderland to complete the negotiations.

It was arranged that I should go to London to talk with the Arsenal chairman, Sir Henry Norris, and a director, Mr William Hall. At the same time I was to look over houses similar to the one I had in Sunderland.

As soon as the housing accommodation was settled - and that was not the difficult matter it is today - I met Mr Chapman again to sign the necessary forms.

Before doing so I asked him, as a matter of personal satisfaction, what was the transfer fee.

After a little persuasion he gave me an answer. It was almost as big a shock as the transfer itself.

He said: "Well, it's rather a peculiar one. We pay Sunderland cash down £2,000, and then we hand over £100 to them for every goal you score during your first season with Arsenal."

(11) Herbert Chapman, Herbert Chapman on Football (1935)