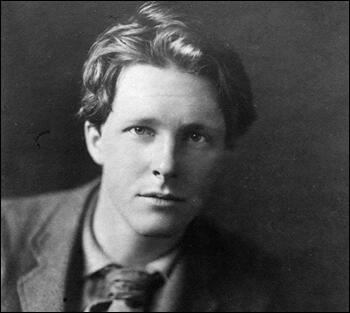

Rupert Brooke

Rupert Chawner Brooke, the second of the three sons born to William Parker Brooke (1850–1910), a housemaster at Rugby School, was born on 3rd August, 1887. According to his biographer, Adrian Caesar: "Brooke attended a preparatory school, Hillbrow, as a day boy, 1897–1901, and then proceeded to take his place at Rugby. Home and school thus became the same place, and psychologically this situation may have represented the worst of both worlds: he experienced the sexually sequestered and confusing world of the public school, while simultaneously coping with the emotional intensities generated by a possessive mother and a distantly affectionate father."

In 1906 he won a scholarship to King's College. While at Cambridge University Brooke joined the Fabian Society. Other members at Cambridge at the time included: Hugh Dalton, Clifford Allen and Amber Reeves. During this period Brooke met several leaders of the movement including George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, Beatrice Webb and Sidney Webb. Like fellow members he developed an enthusiasm for long walks, camping, nude bathing, and vegetarianism.

Brooke wrote at the time about the Fabians: "they're really sincere, energetic, useful people, and they do a lot of good work." He was especially impressed with Wells who he described as being "fantastic". However, he was more critical of other members. He wrote that he wanted the Fabians to take "a more human view... They confound the means with the end; and think that a compulsory living wage is the end, instead of a good beginning."

Beatrice Webb established the National Committee for the Break-Up of the Poor Law. According to the authors of The First Fabians (1977): "Beatrice directed a campaign of meetings, conferences, summer schools, study circles and propaganda leaflets which within a few months had recruited over sixteen thousand members and had set up branches across the country. Its energies came largely from young people. Rupert Brooke, pedalling around the Cambridgeshire villages with his campaign literature, collected the litany of names for his famous poem on Grantchester, and many aspiring politicians on the left served their apprenticeship in the campaign."

Brooke began writing poetry and during the next few years had two collections of verse published, Poems (1911) and Georgian Poetry (1913). Adrian Caesar argues: "Despite this parade of achievement, Brooke's private life proceeded from confusion to chaos and crisis. Paradoxically, his emotional and his psychosexual life were ruled by the puritanism which he dissected in his academic writing. To a revulsion from the body he added a deep uncertainty as to the direction of his desires.... James Strachey also remained a close friend during this period, although Brooke refused at least two invitations to share his bed. Further chaste entanglements developed in 1910 and 1911 with Katherine (Ka) Laird Cox (1887–1938) and Elisabeth van Rysselberghe (1889/90–1980) respectively. Brooke's unresolved relationships with Noel and Ka precipitated a nervous breakdown in early 1912, following which he consummated his relationship with Ka. But this led to more misery, and there is some evidence to suggest that Ka bore his stillborn child later that year."

On the outbreak of the First World War Brooke joined the Royal Naval Division and in October 1914 took part in the Antwerp expedition. After this experience he wrote several poems which made him famous including, Peace, Safety and The Soldier. These poems are now considered as representative of the naïve patriotism of Brooke's generation.

In February 1915 Brooke sailed on the Grantully Castle for the Dardanelles. While on board he developed acute blood poisoning and although transferred to a hospital ship died on 23rd April 1915. Rupert Brooke was buried on the Greek island of Skyros.

Primary Sources

(1) Rupert Brooke, Peace (1914)

Now, God be thanked who has matched us with his hour,

And caught our youth, and wakened us from sleeping,

With hand made sure, clear eye, and sharpened power,

To turn, as swimmers into cleanness leaping.

Glad from a world grown old and cold and weary,

Leave the sick hearts that honour could not move,

And half-men, and their dirty songs and dreary,

And all the little emptiness of love!

Oh! we, who have known shame, we have found release there,

Where there's no ill, no grief, but sleep is mending,

Naught broken save the body, lost but breath;

Nothing to shake the laughing heart's song peace there

But only agony, and that has ending;

And the worst friend and enemy is but Death.

(2) Rupert Brooke, The Soldier (1914)

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there's some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;

A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware,

Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam,

A body of England's, breathing English air,

Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home.

And think, this heart, all evil shed away,

A pulse in the eternal mind, no less

Gives somewhere back the thoughts by England given;

Her sights and sounds; dreams happy as her day;

And laughter, learnt of friends; and gentleness,

In hearts at peace, under an English heaven.