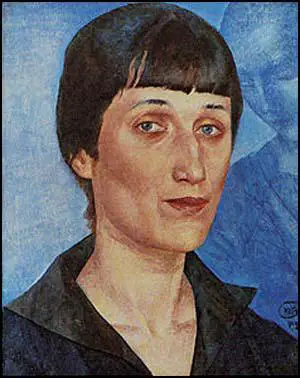

Anna Akhmatova

Anna Akhmatova, the daughter of a naval engineer, was born near Odessa, on 23rd June, 1889. Her family moved to Tsarskoye Selo when she was a child. She moved to Kiev after her parents separated in 1905. She went on to study law at Kiev University, leaving a year later to study literature in Saint Petersburg.

She met the young poet, Nikolai Gumilev on Christmas Eve 1903 and the couple began giving poetry readings together. Gumilev's friend, Victor Serge pointed out: "Nikolai Gumilev was rather lean and singularly ugly: his face too long, heavy lips and nose, conical forehead, weird eyes, bluish-green and over-large, like a fish or Oriental idol - and indeed, he was very fond of the priestly statues of Assyria, which everyone came to think he resembled." Gumilev's first book of poetry, The Path of the Conquistadores was published in 1905. He also established a journal, Sirius, and in 1907 began publishing Anna's poetry. Gumilev also published Romantic Flowers (1908) and Pearls (1910). Anna married Gumilev in Kiev in April 1910.

In 1911 Anna joined with Gumilev, Sergey Gorodetsky and Osip Mandelstam to form the Guild of Poets. This was formed as a reaction to the Symbolist movement, the Acmeists, as they became known, called for a return to the use of clear, precise and concrete imagery. Gumilev was interested in the culture of Africa and Asia and in 1911 visited Abyssinia where he collected folk songs.

Akhmatova's first volume of poetry, Evening , was published in 1912. The book secured her reputation as an important new poet. Her second collection, The Rosary appeared in March 1914. Her work was much imitated and she commented: "I taught our women how to speak, but don't know how to make them silent" It was rumoured that during this period she had affairs with Boris Pasternak and Alexander Blok.

On the outbreak of the First World War her husband, Nikolai Gumilev, joined the Russian Army and while serving as an officer on the Eastern Front was twice decorated for bravery. He described some of his experiences in Notes of a Cavalryman (1916). A supporter of the Provisional Government Gumilev was sent by Alexander Kerensky to Paris where he served as a special commissar in France.

In 1918, Anna divorced Gumilev and married the poet Vladimir Shilejko. According to R. Eden Martin, she later said: “I felt so filthy. I thought it would be like a cleansing, like going to a convent, knowing you are going to lose your freedom.” Anna also began affairs with the poet, Boris Anrep and the composer Arthur Lourié, who set many of her poems to music.

A strong opponent of the Bolshevik government, Nikolai Gumilev supported the Kronstadt Uprising in March, 1921. After the defeat of the Kronstadt sailors in March, 1917, he was arrested and charged with being involved in an anti-government conspiracy. One of his friends asked Felix Dzerzhinsky, the head of Cheka, to spare Gumilev because of his artistic talent. Dzerhinsky answered, "Are we entitled to make an exception of a poet and still shoot the others?"

Gumilev was executed on 24th August, 1921. According to Victor Serge: "It was dawn, at the edge of a forest, when Gumilev fell, his cap pulled down over his eyes, a cigarette hanging from his lips, showing the same calm he had expressed in one of the poems he brought back from Ethiopia: "And fearless I shall appear before the Lord God." That, at least, is the tale as it was told to me."

The Soviet authorities kept a close watch on Anna Akhmatova and after 1925 they would not allow anything of hers to be published. She survived by working in the library of an agricultural institute, by translating and writing critical studies of Alexander Pushkin and Benjamin Constant. She remained a close friend of Osip Mandelstam and was with him when he was arrested in 1934 for writing an epigram about Joseph Stalin: "His fingers are fat as grubs and the words, final as lead weights, fall from his lips... His cockroach whiskers leer and his boot tops gleam... the murderer and peasant slayer". It has been described as as a "sixteen line death sentence."

In March 1938 her son Lev Gumilyov was arrested. She wrote: For seventeen months I've been crying out/Calling you home/I've flung myself at the hangman's feet/You are my son and my horror/Everything is confused forever/And it's not clear to me/Who is a beast now, who is a man/How long before the execution." He was eventually released from prison in Siberia and was forced to serve in the Red Army during the Second World War.

When the Germans surrounded Leningrad in the autumn of 1941, Andrei Zhdanov ordered Akhmatova and Mikhail Zoshchenko to be flown over the German lines to Moscow and from there to Tashkent, where they spent the rest of the war. In 1945 Lev Gumilyov was arrested again and returned to a Gulag Camp.

In 1945 Isaiah Berlin visited the Soviet Union and asked to meet Akhmatova. Michael Ignatieff, the author of A Life of Isaiah Berlin (1998) has pointed out: "Akhmatova herself had a room looking over the courtyard at the end of the hall. It was bare and denuded: no carpets on the floor or curtains at the windows, just a small table, three chairs, a wooden chest, a sofa, and near the bed a drawing of Akhmatova - head bent, reclining on a couch - rapidly sketched by her friend Amedeo Modigliani during her visit to Paris in 1911. It was the only icon of a Europe she had last seen thirty-four years before. Now stately, grey-haired, with a white shawl around her shoulders, she rose to greet her first visitor from that lost continent."

Berlin wrote in Personal Impressions (1980): Akhmatova was immensely dignified, with unhurried gestures, a noble head, beautiful, somewhat severe features, and an expression of immense sadness. I bowed - it seemed appropriate, for she looked and moved like a tragic queen - thanked her for receiving me, and said that people in the West would be glad to know that she was in good health, for nothing had been heard of her for many years.... Akhmatova asked me about the ordeal of London during the bombing: I answered as best I could, feeling acutely shy and constricted by her distant, somewhat regal manner."

Akhmatova was readmitted to Union of Writers in 1951 and after the death of Joseph Stalin she was allowed to publish her poetry. In 1956 Lev Gumilyov was allowed to return from Siberia. Akhmatova's Poems was published in 1958. This was followed by Poems: 1909–1960 (1961).

Isaiah Berlin met her again in Oxford in 1965: "Akhmatova described the details of the attack upon her by the authorities. She told me that Stalin was personally enraged by the fact that she, an apolitical, little-published writer, who owed her security largely to having contrived to live comparatively unnoticed during the early years of the Revolution, before the cultural battles which often ended in prison camps or execution, had committed the sin of seeing a foreigner without formal authorisation, and not just a foreigner, but an employee of a capitalist government... She knew, she said, that she had not long to live: the doctors had made it plain that her heart was weak, and therefore she was patiently waiting for the end; she detested the thought that she might be pitied; she had faced horrors and knew the most terrible depths of grief, and had exacted from her friends the promise that they would not allow the faintest gleam of pity to show itself, to suppress it instantly if it did; some had given way to this feeling, and with them she had been obliged to part; hatred, insults, contempt, misunderstanding, persecution, she could bear, but not sympathy if it was mingled with compassion."

Anna Akhmatova died on 5th March, 1966.

Primary Sources

(1) Michael Ignatieff, A Life of Isaiah Berlin (1998)

Isaiah had read Zoshchenko's Scenes from the Bathhouse, but as for Akhmatova's poetry, he had read nothing at all. She was just a fabled name from the vanished Czarist past, known to him because Maurice Bowra had translated some of her early poems and had included them in his war-time collection of Russian verse. Bowra did not even know whether she was still alive. So Isaiah asked, in all innocence, whether she was, and the critic Orlov replied, to his astonishment, "Why, yes of course, she lives not far from here on the Fontanka in Fontanny Dom".

"Would you like to meet her?" It was, Isaiah remembered, as if he had been invited to meet Christina Rossetti or some semi-mythological figure from the history of literature. In his excitement, he could only stammer that he would indeed like to meet her. There and then Orlov made a phone-call and returned to say that the poet would receive them that very afternoon at three o'clock. Isaiah returned Brenda Tripp to the Astoria and walked back to the bookshop.

In company with Orlov, he set off across the Anichkov Bridge, with its statues of rearing bronze horses, along the Fontanka Canal on a snowy, grey afternoon in failing light. Fontanny Dom was the eighteenth-century palace of the Sheremetiev family. Its baroque yellow and white plasterwork was pitted with shell fragments and in places worn away by neglect. They passed beneath the Sheremetiev crest over the baroque entrance, through rococo iron gates and into the interior courtyard. Berlin and Orlov went up a dark, steep staircase to a third-floor apartment - No. 44 - past five or six rooms ranged along a corridor. Most of the apartment was occupied by Akhmatova's ex-husband, Nikolai Punin, his wife and child. Akhmatova herself had a room looking over the courtyard at the end of the hall. It was bare and denuded: no carpets on the floor or curtains at the windows, just a small table, three chairs, a wooden chest, a sofa, and near the bed a drawing of Akhmatova - head bent, reclining on a couch - rapidly sketched by her friend Amedeo Modigliani during her visit to Paris in 1911. It was the only icon of a Europe she had last seen thirty-four years before. Now stately, grey-haired, with a white shawl around her shoulders, she rose to greet her first visitor from that lost continent. Isaiah bowed - it seemed appropriate - for she looked like a tragic queen.

She was twenty years older than he, once a famous beauty, now shabbily dressed, heavy, with shadows beneath her dark eyes, but of proud carriage and coolly dignified expression. As they sat down on rickety chairs at opposite ends of the room and began talking, Isaiah knew her only as the brilliant and beautiful member of the pre-revolutionary poetic circle known as the Acmeists; as the brightest star of St Petersburg's war-time avant-garde and its meeting place, the Stray Dog Cafe. But of what had befallen her after the revolution, he knew nothing.

There was nothing falsely melodramatic about her tragic air. Her first husband, Nikolai Gumilyov, had been executed in 1921 on trumped-up charges of plotting against Lenin. The years of terror had begun for her then, and not in 1937. Although she wrote continuously, she was not allowed to publish a line of her poetry between 1925 and 1940. During that time she had survived by working in the library of an agricultural institute, by translating and writing critical studies of Pushkin and Western writers like Benjamin Constant. As all contact with the outside world was severed, Akhmatova and her fellow-poet Osip Mandelstam kept alive a fierce conviction that the tyranny that had divided them from Paris, London and Berlin would not endure for ever....

Akhmatova had been there on the night in 1934 when Mandelstam was taken away for his first interrogation; and from then until his death in Magadan she stood by his wife, Nadezhda. But in March 1938 the weight of the terror fell upon her directly. Her son Lev Gumilyov was arrested. For seventeen months she had no idea whether he was alive or dead. As terror sealed the lips of those around her, she made herself the poet of despair and abandonment...

During her war-time evacuation to Tashkent between 1941 and 1944, Akhmatova lived in a airless top-floor room in the Hostel for Moscow Writers. Lydia Chukovskaya and Nadezhda Mandelstam lived there too, and for a time their conditions were eased. Akhmatova was allowed to publish a severely censored volume of Selected Poems and gave readings in hospitals for wounded soldiers. In May 1944 she was at last allowed to leave Tashkent. On her way home, she stopped in Moscow and gave a reading at the Polytechnic Museum, which ended with the audience rising and applauding her as a national figure, the incarnation of the victorious Russian language. She herself was terrified by this mark of respect and feared the attention it brought. She was right to do so, for, as Pasternak reported to her, Stalin himself supposedly asked Zhdanov, "Who organised this standing ovation?"

Akhmatova's return to Leningrad, in June 1944, proved to be desolate: the city was a 'horrible spectre'; so many of her friends were dead; her rooms in the Fontanny Dom had been looted and smashed. She had hopes of being reunited with Victor Garshin, a Leningrad coroner with whom she had become close after leaving Punin. He met her at the station and told her that he had decided to marry someone else." So, as she was meeting Isaiah, she was just coming to terms, at the age of fifty-six, with the prospect of living the rest of her life alone.

In the late summer of 1945 her son Lev, released earlier from Siberia to serve in the Soviet Army in Germany, at last returned home. She allowed herself to hope that her life might finally be about to improve. Certainly, without the fact of Lev's recent release - and thus the liberation of the hostage whose fate might have inclined her to caution - it is doubtful that she would have taken the risk of seeing a temporary First Secretary from the British Embassy in Moscow...

But she was categorical about the question of emigration. Salome Andronikova, Boris Anrep and others might choose the road of exile, but she would never leave Russia. Her place was with her people and with her native language. And so the night acquired another significance for her: it was a moment in which to re-affirm her sense of destiny as the all enduring Muse of her native tongue. Isaiah was quite sure he had never met anyone with such a genius for self-dramatisation - but, at the same time, he recognised that her claim to a tragic destiny was as genuine as that of anyone he had ever met...

She told him of her marriage to Gumilyov and how, despite their separation and divorce, she had always remembered the laconic and unquestioning way he had accepted her talent. When she described the circumstances of his execution in 1921, tears came to her eyes. Then she began to recite from Byron's Don Juan. Her pronunciation was unintelligible, but she delivered the lines with such intense emotion that Isaiah had to rise and look out of the window to conceal his feelings...

She confessed how lonely she was, how desolate her Leningrad had become. She spoke of her past loves, for Gumilyov, Shileiko and Punin, and, moved by her confessional mode - but also perhaps to forestall her erotic interest in him - Isaiah confessed that he was in love with someone himself. He was veiled, but it was clear that he was referring to Patricia Douglas. Akhmatova seems to have passed on a wildly garbled version of these remarks about his love-life to Korney Chukovsky, whose memoirs, published years later, referred to Berlin as a Don Juan disembarking in Leningrad to add Akhmatova to the list of his conquests." Akhmatova herself seems to have been responsible for this malentendu. It has hung over their encounter ever since. No Russian who reads Cinque, the poems she devoted to their evening together, has ever been able to believe that they did not sleep together.

In fact, they hardly touched. He remained on one side of the room, she on the other. Far from being a Don Juan, he was a sexual neophyte alone in the apartment of a fabled seductress, who had enjoyed deep romantic attachments with half a dozen supremely talented men. She was already investing their meeting with mystical historical and erotic significance, while he fought shy of these undercurrents and kept a safe intellectual distance. Besides, he was also aware of more quotidian needs. He had already been there six hours and he wanted to go to the lavatory. But it would have broken the mood to do so, and in any case, the communal toilet was down the dark hallway. So he remained and listened, smoking another of his Swiss cigars. As she poured out the story of her love-life, he compared her to Donna Anna in Don Giovanni and, moving his cigar hand to and fro - a gesture she was to capture in a line of verse - traced Mozart's melody in the air between them.

(2) Anna Akhmatova, Lev Gumiyov (1938)

For seventeen months I've been crying out,

Calling you home.

I've flung myself at the hangman's feet,

You are my son and my horror.

Everything is confused forever,

And it's not clear to me

Who is a beast now, who is a man,

How long before the execution.

(3) Michael Ignatieff, A Life of Isaiah Berlin (1998)

The last of Isaiah's encounters with the great figures of the Russian intelligentsia occurred in 1965, when he and Maurice Bowra managed to persuade their university to grant Anna Akhmatova an honorary degree. He had telephoned her in Moscow in 1956, and she had received the news of his marriage in icy silence. They had both decided it was not safe to meet. When she duly appeared in Oxford in June 1965, Isaiah was shocked to see how she had aged. She had gained weight and he thought, a little unkindly, that she resembled Catherine the Great. But she carried herself like an empress and delivered herself of her opinions with imperial force. When she arrived outside Headington House and surveyed the splendid garden, the three-storey Georgian house and Isaiah's new wife, she observed caustically: "So the bird is now in its golden cage." The spark that had leaped between them twenty years before was now extinguished. He could only secure her the recognition in the West that was her due; she could only acknowledge it with regal hauteur. He accompanied her as she stood in the Sheldonian and heard herself acclaimed in Latin as "an embodiment of the past, who can console the present and provide hope for the future". Afterwards he was in attendance at the Randolph Hotel when she received Russian visitors who had come from all over the world to pay court to her. He was there too when she read from her verse, intoning the deep and sonorous rhythms into a tape recorder. She departed for Paris and home, and Isaiah never saw her again. She died the following year. His anti-communism had always been a declaration of allegiance to the intelligentsia of whom she was the last surviving heroine. After her death, he exclaimed to a friend that he would always think of her as an "uncontaminated", "unbroken" and "morally impeccable" reproach to all the Marxist fellow-travellers who believed that individuals could never stand up to the march of history.

(4) Isaiah Berlin, Personal Impressions (1980)

Anna Andrecvna Akhmatova was immensely dignified, with unhurried gestures, a noble head, beautiful, somewhat severe features, and an expression of immense sadness. I bowed - it seemed appropriate, for she looked and moved like a tragic queen - thanked her for receiving me, and said that people in the West would be glad to know that she was in good health, for nothing had been heard of her for many years. "Oh, but an article on me has appeared in the Dublin Review," she said, "and a thesis is being written about my work, I am told, in Bologna." She had a friend with her, an academic lady of some sort, and there was polite conversation for some minutes. Then Akhmatova asked me about the ordeal of London during the bombing: I answered as best I could, feeling acutely shy and constricted by her distant, somewhat regal manner.

(5) Isaiah Berlin, Personal Impressions (1980)

When we met in Oxford in 1965, Akhmatova described the details of the attack upon her by the authorities. She told me that Stalin was personally enraged by the fact that she, an apolitical, little-published writer, who owed her security largely to having contrived to live comparatively unnoticed during the early years of the Revolution, before the cultural battles which often ended in prison camps or execution, had committed the sin of seeing a foreigner without formal authorisation, and not just a foreigner, but an employee of a capitalist government. "So our nun now receives visits from foreign spies," he remarked (so it is alleged), and followed this with obscenities which she could not at first bring herself to repeat to me. The fact that I had never worked in any intelligence organisation was irrelevant: all members of foreign embassies or missions were spies to Stalin. "Of course," she went on, "the old man was by then out of his mind. People who were there during this furious outbreak against me, one of whom told me of it, had no doubt that they were speaking to a man in the grip of pathological, unbridled persecution mania." On the day after I left Leningrad, on 6 January 1946, uniformed men had been placed outside the entrance to her staircase, and a microphone was screwed into the ceiling of her room, plainly not for intelligence purposes but to frighten her. She knew that she was doomed - and although official disgrace followed only some months later, after the formal anathema pronounced over her and Zoshchenko by Zhdanov, she attributed her misfortunes to Stalin's personal paranoia. When she told me this in Oxford, she added that in her view we - that is, she and I - inadvertently, by the mere fact of our meeting, had started the Cold War and thereby changed the history of mankind. She meant this quite literally; and, as Amanda Haight testifies in her book, was totally convinced of it, and saw herself and me as world-historical personages chosen by destiny to begin a cosmic conflict (this is indeed directly reflected in one of her poems). I could not protest that she had perhaps, even if the reality of Stalin's violent fit of anger and of its possible consequences were allowed for, somewhat overestimated the effect of our meeting on the destinies of the world, since she would have felt this as an insult...

She knew, she said, that she had not long to live: the doctors had made it plain that her heart was weak, and therefore she was patiently waiting for the end; she detested the thought that she might be pitied; she had faced horrors and knew the most terrible depths of grief, and had exacted from her friends the promise that they would not allow the faintest gleam of pity to show itself, to suppress it instantly if it did; some had given way to this feeling, and with them she had been obliged to part; hatred, insults, contempt, misunderstanding, persecution, she could bear, but not sympathy if it was mingled with compassion - would I give her my word of honour? I did, and have kept it. Her pride and dignity were very great.