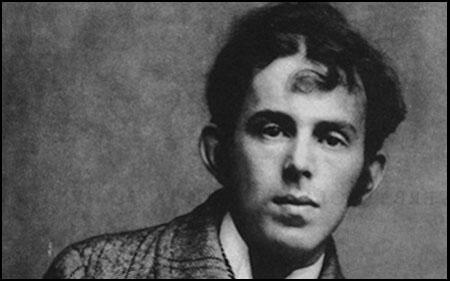

Osip Mandelstam

Osip Mandelstam, the son of wealthy Jewish parents, was born in Warsaw, on 3rd January, 1891. His father, a successful leather merchant, was able to receive a dispensation that enabled them to move to Saint Petersburg.

His first poems were printed in 1907 in the school's almanac.He studied at the University of St. Petersburg, the Sorbonne in France, and the University of Heidelberg in Germany.

Mandelstam's poems also appeared in the journal Apollon in 1910. The following year he joined with Nikolai Gumilev and Sergey Gorodetsky to form the Guild of Poets. Formed as a reaction to the Symbolist movement, the Acmeists, as they became known, called for a return to the use of clear, precise and concrete imagery.

His first volume of poetry, Stone, appeared in 1913. Mandelstam met Nadezhda Khazina in Kiev. in 1919. They married three years later. They moved to Petrograd in 1922 but later settled in Moscow. His books during this period included Tristia (1922), The Noise of Time (1925) and a collection of essays, The Egyptian Stamp (1928). Mandelstam also worked as a journalist. He also translated classic books into Russian.

Osip Mandelstam was hostile to the Communist government and his poetry never conformed to the official doctrine of Socialist Realism. His work became increasingly hostile to the government of Joseph Stalin. During a holiday in Crimea he witnessed the result of Stalin's collectivisation programme.

In 1934 Mandelstam wrote an epigram about Stalin: His fingers are fat as grubs and the words, final as lead weights, fall from his lips... His cockroach whiskers leer and his boot tops gleam... the murderer and peasant slayer". It has been described as as a "sixteen line death sentence." Mandelstam was arrested and exiled to Cherdyn.

Mandelstam was allowed to return to Moscow in May, 1937. During the Great Purge, Mandelstam was attacked for his unwillingness to adopt Socialist Realism and he was accused of holding anti-Soviet views. In 1938 he was arrested and and charged with "counter-revolutionary activities" and was sentenced to five years in correction camps.

Nadezhda Khazina later wrote: "The principles and aims of mass terror have nothing in common with ordinary police work or with security. The only purpose of terror is intimidation. To plunge the whole country into a state of chronic fear, the number of victims must be raised to astronomical levels, and on every floor of every building there must always be several apartments from which the tenants have suddenly been taken away. The remaining inhabitants will be model citizens for the rest of their lives - this was true for every street and every city through which the broom has swept. The only essential thing for those who rule by terror is not to overlook the new generations growing up without faith in their elders, and keep on repeating the process in systematic fashion."

Mandelstam wrote to his wife in October, 1938: "My health is very bad, I'm extremely exhausted and thin, almost unrecognizable, but I don't know whether there's any sense in sending clothes, food and money. You can try, all the same, I'm very cold without proper clothes." The Soviet government reported that Osip Mandelstam died at Vtoraya Rechka, on 27th December, 1938.

Primary Sources

(1) Osip Mandelstam's poem on Joseph Stalin (the Kremlin mountaineer) was written in November, 1933. Ossette was a reference to the rumour that Stalin was from a people of Iranian stock that lived in an area north of Georgia.

We live, deaf to the land beneath us,

Ten steps away no one hears our speeches,

All we hear is the Kremlin mountaineer,

The murderer and peasant-slayer.

His fingers are fat as grubs

And the words, final as lead weights, fall from his lips,

His cockroach whiskers leer

And his boot tops gleam.

Around him a rabble of thin-necked leaders -

fawning half-men for him to play with.

The whinny, purr or whine

As he prates and points a finger,

One by one forging his laws, to be flung

Like horseshoes at the head, to the eye or the groin.

And every killing is a treat

For the broad-chested Ossete.

(2) When Osip Mandelstam was being investigated by the Secret Police he went to see the short-story writer, Isaac Babel, a leading figure in the Union of Soviet Writers. The meeting was later recorded by Mandelstam's wife, Nadezhda Khazina.

The next person we consulted was Babel. We told him our troubles, and during the whole of our long conversation he listened with remarkable intentness. Everything about Babel gave an impression of all-consuming curiosity - the way he held his head, his mouth and chin, and particularly his eyes. It is not often that one sees such undisguised curiously in the eyes of a grown-up. I had the feeling that Babel's main driving force was the unbridled curiously with which he scrutinized life and people.

With his usual ability to size things up, he was quick to decide on the best course for us. "Go out to Kalinin," he said, "Nikolai Erdman is there - his old woman just love him." This was Babel's cryptic way of saying that all Erdman's female admirers would never have allowed him to settle in a bad place. He also thought we might be able to get some help from them - in finding a room there, for instance. Babel volunteered to get the money for our fare the next day.

(3) Osip Mandelstam managed to send this letter to his wife while waiting at a transit labour camp in October, 1937. It was the last letter that she received from him.

My darling Nadia - are you alive, my dear?

I was given five years for counter-revolutionary activity by the Special Tribunal. The transport left Butyrki on September 9, and we got here October 12. My health is very bad, I'm extremely exhausted and thin, almost unrecognizable, but I don't know whether there's any sense in sending clothes, food and money. You can try, all the same, I'm very cold without proper clothes.

I am in Vladivostok. This is a transit point. I've not been picked for Kolyma and may have to spend the winter here.

(4) After Osip Mandelstam's death, Nadezhda Khazina wrote about their experiences of living in the Soviet Union during the 1930s in her book, Hope Against Hope (1970)

In the period of the Yezhov terror - the mass arrests came in waves of varying intensity - there must sometimes have been no more room in the jails, and to those of us still free it looked as though the highest wave had passed and the terror was abating. After each show trial, people sighed, "Well, it's all over at last." What they meant was: "Thank God, it looks as though I've escaped. But then there would be a new wave, and the same people would rush to heap abuse on the "enemies of the people."

Wild inventions and monstrous accusations had become an end in themselves, and officials of the secret police applied all their ingenuity to them, as though reveling in the total arbitrariness of their power.

The principles and aims of mass terror have nothing in common with ordinary police work or with security. The only purpose of terror is intimidation. To plunge the whole country into a state of chronic fear, the number of victims must be raised to astronomical levels, and on every floor of every building there must always be several apartments from which the tenants have suddenly been taken away. The remaining inhabitants will be model citizens for the rest of their lives - this was true for every street and every city through which the broom has swept. The only essential thing for those who rule by terror is not to overlook the new generations growing up without faith in their elders, and keep on repeating the process in systematic fashion.

Stalin ruled for a long time and saw to it that the waves of terror recurred from time to time, always on even greater scale than before. But the champions of terror invariably leave one thing out of account - namely, that they can't kill everyone, and among their cowed, half-demented subjects there are always witnesses who survive to tell the tale.