Harold Ross

Harold Ross, the son of Irish immigrant George Ross and schoolteacher Ida Martin Ross, was born in Aspen, Colorado, on 6th November, 1892. When he was a child his family moved to Silverton before settling in Salt Lake City, Utah.

At the age of thirteen he became a reporter on the Salt Lake City Tribune . He also worked for The Denver Post, Marysville Appeal-Democrat in California, the Sacramento Union, the New Orleans Item-Tribune, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle and the San Francisco Call and Post. He also worked for several magazines. The journalist, Richard O'Connor, commented: "The unpolished but ambitious Ross, formerly a wandering newspaperman, Western-born, and determinedly anti-metropolitan, was rattling around the magazine world trying to find a footing."

During the First World War Ross enlisted in the U.S. Army Eighteenth Engineers Railway Regiment. He was later assigned to the recently established Stars and Stripes, a weekly newspaper by enlisted men for enlisted men. Ross was appointed editor and others working on the newspaper included Alexander Woollcott, Cyrus Leroy Baldridge, Grantland Rice, Adolf Shelby Ochs, Stephen Early and Guy Viskniskki. Another recruit was Franklin Pierce Adams whose main contribution was a column entitled "The Listening Post". Woollcott introduced Ross to Jane Grant and she later admitted she did the "sewing and mending" for all of the soldiers working on the newspaper. Grant became romantically involved with Ross. Although she later commented: "No one, not even his prejudiced mother, could deny that his body was badly put together."

Ross went to live in New York City after the war where he worked for the American Legion Weekly. Soon afterwards he became editor of Judge Magazine, a comic weekly. He took lunch with a group of writers, artists and actors in the dining room at the Algonquin Hotel. This included Robert E. Sherwood, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Alexander Woollcott, Heywood Broun, Donald Ogden Stewart, Edna Ferber, Ruth Hale, Franklin Pierce Adams, Jane Grant, Neysa McMein, Alice Duer Miller, Charles MacArthur, Marc Connelly, George S. Kaufman, Beatrice Kaufman , Frank Crowninshield, Ben Hecht, John Peter Toohey, Lynn Fontanne, Alfred Lunt and Ina Claire. This group eventually became known as the Algonquin Round Table.

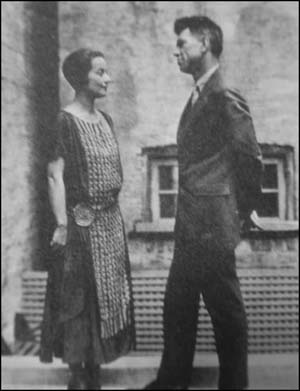

In 1920 Ross married Jane Grant in the Church of the Transfiguration in Manhattan. However, she refused to be known as Mrs. Grant. She later recalled: "Never for a moment had I considered the possibility of losing my name." Grant said she and Ross agreed to give each other complete independence. At the time Ross was working for the Judge Magazine and Grant the New York Times.

For a while Ross and Grant shared a house with the journalists, Heywood Broun and Ruth Hale. Whereas Broun was sympathetic to feminism, Ross was not. According to Howard Teichmann, Ross, particularly after drinking whiskey, told anyone who would listen, "I never had one damn meal at home at which the discussion wasn't of women's rights and the ruthlessness of men in trampling women. Grant and Ruth Hale had maiden-name phobias, and that was all they talked about, or damn near all."

Samuel Hopkins Adams, the author of Alexander Woollcott: His Life and His World (1946), has argued: "The Algonquin profited mightily by the literary atmosphere, and Frank Case evinced his gratitude by fitting out a workroom where Broun could hammer out his copy and Benchley could change into the dinner coat which he ceremonially wore to all openings. Woollcott and Franklin Pierce Adams enjoyed transient rights to these quarters. Later Case set aside a poker room for the whole membership." The poker players included Ross, Heywood Broun, Alexander Woollcott, Herbert Bayard Swope, Robert Benchley, George S. Kaufman, Deems Taylor, Laurence Stallings, Harpo Marx, Jerome Kern and Prince Antoine Bibesco.

On one occasion, Woollcott lost four thousand dollars in an evening, and protested: "My doctor says it's bad for my nerves to lose so much." It was also claimed that Harpo Marx "won thirty thousand dollars between dinner and dawn". Howard Teichmann, the author of George S. Kaufman: An Intimate Portrait (1972) has argued that Broun, Adams, Benchley, Ross and Woollcott were all inferior poker players, Swope and Marx were rated as "pretty good" and Kaufmann was "the best honest poker player in town."

Grant and Ross developed ideas about publishing their own magazine. In her book, Ross, The New Yorker and Me (1968) Grant argued: "Ross had great humility then. He assured me he'd try anything I decided upon, that he wanted to be anything I wanted him to be. I’m afraid I did a good deal of prodding. But I felt he really could accomplish what he set out to do - with his talent and his enormous drive - even though many people doubted his ability. He would have given up, I am sure, if I hadn’t encouraged him; fortunately I was able to influence him."

According to Beverly G. Merrick: "The couple agreed that they would attempt to live on her earnings, and save his salary of $10,000 for a magazine of his own invention. Grant said she persuaded Ross to put his ideas on paper. He reportedly had three in mind: a high-class tabloid, a shipping magazine and a weekly about life in Manhattan. Ross and Grant were opposites in the truest sense of the word. For instance, Ross was tone deaf and could not abide her dancing, singing or whistling around him. But as is often true in the case of opposites, it took that combination to make the magazine reach fruition. Grant had a good business sense. Ross had a unique sense of humor, the kind of humor that would come to characterize The New Yorker. Grant encouraged him to go with the third idea. She intuitively knew that it would best suit him, as well be a success in the marketplace. It apparently took them five years to raise the capital for the venture."

Ross approached Raoul Fleischmann in 1925 about funding a new magazine, The New Yorker. Fleischmann later recalled: "I wasn't at all impressed with Ross' knowledge of publishing, I had no reason to doubt his skill as an editor, nor any reason to believe in it." Despite these comments he agreed to invest $45,000 in the magazine. The first edition appeared on 21st February, 1925. Early editions were not very popular. Marion Meade has pointed out: "Five months after its birth, the magazine's original capital was depleted and it seemed unlikely to survive the summer season, customarily a slow period even for prosperous publications. Raoul Fleischmann had been advised that the wisest course would be to suspend publication until the fall, but Harold Ross and Jane Grant were convinced that this would mean ruin for the magazine. They had begun to seek capital elsewhere. In the midst of Adams's nuptial festivities, Fleischmann arrived with a miraculous last minute reprieve and announced that he had persuaded his mother to invest $100,000, enough to assure the summer issues at least."

Initially the magazine concentrated on the social and cultural life of New York City but eventually widened its scope and developed a reputation for publishing some of the best short-stories, cartoons, biographical profiles, foreign reports and arts reviews. Its contributors included Dorothy Parker (poems and short-stories), Robert Benchley (theatre critic), James Thurber (cartoons and short-stories), Elwyn Brooks White, John McNulty, Joseph Mitchell, Katharine S. White (also fiction editor), Sidney J. Perelman, Janet Flanner (correspondent based in Paris), Wolcott Gibbs (theatre critic), St. Clair McKelway and John O'Hara (over 200 of his short-stories appeared in the magazine).

In 1929 one of the most famous journalists in America, Alexander Woollcott, left the New York Times to join the New Yorker. Carr Van Anda, the managing director of the Times, was disappointed by this decision: "In spite of the brusqueness and other peculiarities of conduct developed with his rise in the world which amused or annoyed his friends, according to mood, he was by nature really a sensitive, sometimes almost a shrinking soul. What began as a defence mechanism led to the invention of the almost wholly artificial character, Alexander Woollcott, persistently enacted before the world until it became a profitable investment.... It is a matter of extreme regret to me, as an old friend, that his sacrifice of brilliant gifts and varied acquirements to the dramatization of himself as a personality has left him with a far less secure literary fame than he might well have achieved."

Soon afterwards Ross, and his wife Jane Grant, purchased with Woollcott purchased a large house on West Forty-Seventh Street. They were joined by Hawley Truax, Kate Oglebay and William Powell. She later wrote: "It was a mad, amusing ménage, made up of Aleck, Hawley Truax, Ross and myself as owners and at first there were two others, Kate Oglebay and William Powell, as tenants and participants on the top floor. It soon became the hangout for all the literary and musical crowd and I well remember that on one Sunday evening I had twenty-eight unexpected guests for supper... We all had separate apartments, sharing only the dining-room and kitchen."

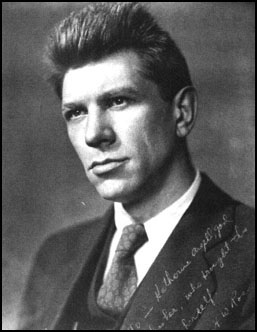

John Keats, the author of You Might as Well Live: The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1971) has commented: "Harold Ross was a young man who looked to be put together all wrong: he wore what looked, on him, to be a farmer's Sunday suit. His hair suggested a picket fence."

Harold Ross remained the controlling influence over the magazine until his death in Boston on 6th December, 1951, during an operation to remove a tumor.

Primary Sources

(1) John Keats, You Might as Well Live: The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1971)

Harold Ross was a young man who looked to be put together all wrong: he wore what looked, on him, to be a farmer's Sunday suit. His hair suggested a picket fence. He had been an itinerant newspaperman before the war; he was new to the city; he dreamed of founding a magazine, and he was regarded by his erstwhile colleagues on Stars and Stripes to be an editor of genius.

(2) Marc Connelly, Voices Offstage (1968)

After The New Yorker was solidly established, Ross, pretending ignorance, would often listen with an imbecilically gaping mouth to something being said by a crony of which he had more knowledge than the speaker. At the conclusion of an incorrect statement he would yell with make-believe fury. "That shows you're a God-damned ignoramus!" and then proceed with lordly politeness to state the facts. However, if a comparative stranger pretentiously said something inaccurate, Ross would merely grunt an acceptant "Uh huh" and walk away.

Sometimes Ross's highly articulate ability to express editorial opinion would be oddly demonstrated. Once when he was being shown an illustration submitted for publication, he was baffled by the perspective. He looked at the picture, running his fingers through his unruly hair. (George Kaufmann once said the jungle scenes in Chang were shot in Ross's pompadour.)

(3) Marion Meade, Dorothy Parker: What Fresh Hell is This? (1989)

Things were going badly when the Round Tablers and their friends gathered to attend Frank Adams's wedding to Esther Root on May 9. The ceremony was performed at the home of friends who lived near Greenwich, Connecticut. A number of the wedding guests arrived in extremely low spirits, because it looked as if The New Yorker would fold. Five months after its birth, the magazine's original capital was depleted and it seemed unlikely to survive the summer season, customarily a slow period even for prosperous publications. Raoul Fleischmann had been advised that the wisest course would be to suspend publication until the fall, but Harold Ross and Jane Grant were convinced that this would mean ruin for the magazine. They had begun to seek capital elsewhere. In the midst of Adams's nuptial festivities, Fleischmann arrived with a miraculous last minute reprieve and announced that he had persuaded his mother to invest $100,000, enough to assure the summer issues at least.

(4) Beverly G. Merrick, Jane Grant (1999)

The couple agreed that they would attempt to live on her earnings, and save his salary of $10,000 for a magazine of his own invention. Grant said she persuaded Ross to put his ideas on paper. He reportedly had three in mind: a high-class tabloid, a shipping magazine and a weekly about life in Manhattan.

Ross and Grant were opposites in the truest sense of the word. For instance, Ross was tone deaf and could not abide her dancing, singing or whistling around him. But as is often true in the case of opposites, it took that combination to make the magazine reach fruition. Grant had a good business sense. Ross had a unique sense of humor, the kind of humor that would come to characterize The New Yorker.

Grant encouraged him to go with the third idea. She intuitively knew that it would best suit him, as well be a success in the marketplace. It apparently took them five years to raise the capital for the venture.

(5) Jane Grant, Ross, The New Yorker and Me (1968)

Ross had great humility then. He assured me he'd try anything I decided upon, that he wanted to be anything I wanted him to be. I’m afraid I did a good deal of prodding. But I felt he really could accomplish what he set out to do - with his talent and his enormous drive - even though many people doubted his ability. He would have given up, I am sure, if I hadn’t encouraged him; fortunately I was able to influence him.

© John Simkin, April 2013