Neysa McMein

Marjorie (Neysa) McMein, the daughter of Harry McMein and Belle Parker, was born in Quincy, Illinois, on 24th January, 1888. Her father, a former reporter, worked for the family business, the McMein Publishing Company. It was a difficult marriage and the relationship was not helped by McMein's growing alcoholism.

McMein studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and in 1913 moved to New York City. Shortly after arriving she changed her name to Neysa. She briefly attempted to be an actress but in 1914 she began studying at the Art Students League. Later that year she sold her first illustration to Boston Star . In 1915 she did a portrait of Harry Horowitz (Gyp the Blood), the gunman about to be executed for the murder of Herman Rosenthal.

Brian Gallagher, the author of Anything Goes: The Jazz Age of Neysa McMein and her Extravagant Circle of Friends (1987), has pointed out that she was an ardent supporter of women's suffrage. "One of the things Neysa came to New York to be was a fully emancipated woman: socially, sexually, and economically. With her, the matter was more personal than ideological. If she was a feminist... Neysa was one only by example. It was not that she did not participate in some aspects of the women's movement - Neysa was an ardent suffragist... but that she seemed to participate in such things instinctively rather than intellectually."

In 1915 Neysa McMein began producing front covers for the Saturday Evening Post. Her pastel drawings of young women proved highly popular and brought her many commissions. During the First World War she travelled to France and produced posters for the United States and French governments. In the summer of 1918 she spent time on the Western Front. She later recalled: "Since I have lived through air bombing I never will be frightened by anything on earth. The terror of air raids cannot be imagined. They are heralded by the blowing of sirens and the ringing of church bells, and amid this din the lights are extinguished and then suddenly come the bombs, falling no one knows where. The noise they made is worse than that of the battles." While she was in Paris she became friends with Private Harold Ross and Sergeant Alexander Woollcott. Both men were working for the army newspaper, Stars and Stripes.

After the war McMein began taking lunch with a group of writers in the dining room at the Algonquin Hotel in New York City. Murdock Pemberton later recalled that he owner of the hotel, Frank Case, did what he could to encourage this gathering: "From then on we met there nearly every day, sitting in the south-west corner of the room. If more than four or six came, tables could be slid along to take care of the newcomers. we sat in that corner for a good many months... Frank Case, always astute, moved us over to a round table in the middle of the room and supplied free hors d'oeuvre. That, I might add, was no means cement for the gathering at any time... The table grew mainly because we then had common interests. We were all of the theatre or allied trades." Case admitted that he moved them to a central spot at a round table in the Rose Room, so others could watch them enjoy each other's company.

This group eventually became known as the Algonquin Round Table. Other regulars at these lunches included Robert E. Sherwood, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Alexander Woollcott, Heywood Broun, Harold Ross, Donald Ogden Stewart, Edna Ferber, Ruth Hale, Franklin Pierce Adams, Jane Grant, Alice Duer Miller, Charles MacArthur, Marc Connelly, George S. Kaufman, Beatrice Kaufman , Frank Crowninshield, Ben Hecht, John Peter Toohey, Lynn Fontanne, Alfred Lunt and Ina Claire.

Marc Connelly claims that the group spent a lot of time at the studio of Neysa McMein. "The world in which we moved was small, but it was churning with a dynamic group of young people who included Robert C. Benchley, Robert S. Sherwood, Ring Lardner, Dorothy Parker, Franklin. P. Adams, Heywood, Broun, Edna Ferber, Alice Duer Miller, Harold Ross, Jane Grant, Frank Sullivan, and Alexander Woollcott. We were together constantly. One of the habitual meeting places was the large studio of New York's preeminent magazine illustrator, Marjorie Moran McMein, of Muncie, Indiana. On the advice of a nurnerologist, she concocted a new first name when she became a student at the Chicago Art Institute. Neysa McMein. Neysa's studio on the northeast corner of Sixth Avenue and Fifty-seventh Street was crowded all day by friends who played games and chatted with their startlingly beautiful young hostess as one pretty girl model after another posed for the pastel head drawings that would soon delight the eyes of America on the covers of such periodicals as the Ladies' Home Journal, Cosmopolitan, The American and The Saturday Evening Post."

Herbert Bayard Swope, H. L. Mencken, Arthur Krock and Janet Flanner were regular visitors to McMein's studio. H. G. Wells was fascinated with McMein and went to see her everyday when he visited New York City. The writer, George Bernard Shaw was another admirer. The nineteen year-old, Anaïs Nin, went to her studio to pose for her: "I met many celebrities there... it was so enjoyable, so bright and lively". She even told McMein, "It was so wonderful, posing for you, I hate to take the money for it." Another visitor commented: "Neysa had the nearest thing to a salon this country has ever seen... She might be in her smock and serve bad port but everyone came and everyone loved it."

Alexander Woollcott was another regular visitor: "Over at the piano Jascha Heifetz and Arthur Samuels may be trying to find out what four hands can do in the syncopation of a composition never thus desecrated before. Irving Berlin is encouraging them. Squatted uncomfortably around an ottoman, Franklin P. Adams, Marc Connelly and Dorothy Parker will be playing cold hands to see who will buy the dinner that evening. At the bookshelf Robert C. Benchley and Edna Ferber are amusing themselves vastly by thoughtfully autographing her set of Mark Twain for her. In the corner, some jet-bedecked dowager from a statelier milieu is taking it all in, immensely diverted. Chaplin, Alice Duer Miller or Wild Bill Donovan, Father Duffy or Mary Pickford - any or all of them may be there... If you loiter in Neysa McMein's studio, the world will drift in and out. Standing at the easel itself, oblivious of all the ructions, incredibly serene and intent on her work, is the artist herself."

In 1920 her good friend, Dorothy Parker, left her husband and moved in with McMein for a brief period. According to As John Keats, the author of You Might as Well Live: The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1971): "She (Dorothy Parker) had taken an apartment in a building on West Fifty-seventh Street where the beautiful and somewhat Bohemian artist Neysa McMein had a studio. Miss Mcmein was a familiar of the Round Table, and her studio was a nocturnal headquarters for the Algonquin group. But Dorothy had taken the apartment because it was convenient to this meeting place of all her friends, and not for the purpose of sleeping with any of them."

In 1921 McMein, Ruth Hale and Jane Grant established the Lucy Stone League. The first list of members included Heywood Broun, Beatrice Kaufman, Franklin Pierce Adams, Belle LaFollette, Freda Kirchwey, Anita Loos, Zona Gale, Janet Flanner and Fannie Hurst. Its principles were forcefully expressed in a booklet written by Hale: "We are repeatedly asked why we resent taking one man's name instead of another's why, in other words, we object to taking a husband's name, when all we have anyhow is a father's name. Perhaps the shortest answer to that is that in the time since it was our father's name it has become our own that between birth and marriage a human being has grown up, with all the emotions, thoughts, activities, etc., of any new person. Sometimes it is helpful to reserve an image we have too long looked on, as a painter might turn his canvas to a mirror to catch, by a new alignment, faults he might have overlooked from growing used to them. What would any man answer if told that he should change his name when he married, because his original name was, after all, only his father's? Even aside from the fact that I am more truly described by the name of my father, whose flesh and blood I am, than I would be by that of my husband, who is merely a co-worker with me however loving in a certain social enterprise, am I myself not to be counted for anything."

Brian Gallagher, the author of Anything Goes: The Jazz Age of Neysa McMein and her Extravagant Circle of Friends (1987), has argued: "Neysa McMein, as much as any American of the time, typified this contradictory decade. She was charming and eager and sophisticated, but she could be disarmingly provincial. She was liberated and self-supporting and casual - a few would say notoriously caasual - in sexual matters, but she was generally apolitical and still clung, at least nominally, to the rather conservative political tenents of her Republican upbringing in western Illinois."

Marc Connelly claimed: "Neysa couldn't have been more popular. She couldn't have been lovelier. Everybody loved her. She was perfectly beautiful, a tall Amazonian sort of person, handsome as could be." According to George Abbott "every taxi-cab driver, every salesgirl, every reader of columns, knew about the fabulous Neysa." Harpo Marx described her as "the sexiest gal in town" and admitted that "the biggest love affair in New York City was between me - along with two dozen other guys - and Neysa McMein." The screenwriter, Charles Brackett, was another admirer: "Why the bare word hello from her lips, and the way she brushed back her tawny hair with her wrist, should be so luminous with charm was incomprehensible."

Another close friend was Anita Loos: "Neysa was a magnificent young creature, a Brünnhilde with a classic face, tawny hair that scorned a brush or comb, and a style of dress for which her inspiration could only have been a grabbag. But all New York knew she was the heroine of a succession of romances with extremely prominent men. When Neysa invited me to her studio I accepted, but I confess to being critical of her; to me Neysa's unkempt appearance seemed phony and even a little conceited; it was if Cinderella had purposely gone to the ball in rags, knowing they'd make her all the more a sensation."

Alexander Woollcott was strongly attracted to McMein. However, one of his friends suggested he "just wants somebody to talk to in bed." Samuel Hopkins Adams, the author of Alexander Woollcott: His Life and His World (1946) disagreed with this view and argued that Woollcott was very serious about her: "Neysa McMein was a reigning toast of the Algonquin Sophisticates and the object of unrequited passion to several... Woollcott, now cured of his disappointment over Jane Grant, had joined the court of Miss McMein's devotees, where the others never saw any occasion to be jealous of him."

Brian Gallagher, the author of Anything Goes: The Jazz Age of Neysa McMein and her Extravagant Circle of Friends (1987), has written in some detail about his relationship with Woollcott: "Alec constituted Neysa's longest and most constant 'extramarital' relationship... However, because of his stunted sexuality, there was often an unconsummated quality about Alec's quasi-sexual relationships, never more so than in the case of Neysa, who was the most overtly sensuous of all the women to whom he was close. Throughout their relationship the two often played at a coy sexual game based on, or at least allowed by, Alec's near eunuchhood.... Often Neysa was Alec's companion for opening nights. The tall, beautiful Neysa, usually dressed oddly or eccentrically, and the obese, plain Alec, in his dandified cloak and hat, made for a queer-looking couple. It is very doubtful that on such occasions Alec solicited Neysa's theatrical opinions - or that he even gave her sufficient chance to voice them, for Alec's great forte was monologue, not repartee, and Neysa was, apart from his large radio audience, among the most admiring and indulgent of his listeners. From time to time, but less frequently than with some other of his good and true friends, Alec would become overbearing and there would have to be, at Neysa's insistence, a trial separation of some weeks or months."

Dorothy Parker was a regular visitor to McMein's apartment. Parker later claimed that McMein made wine in the bathroom and was always entertaining friends such as Alice Duer Miller, Alexander Woollcott, Ruth Hale, Jane Grant, George Gershwin, Ethel Barrymore and F. Scott Fitzgerald. She added that her friends loved "playing Consequences, Shedding Light, Categories, or a kind of charades that was later called The Game." George Abbott claimed that Nesya was "the greatest party giver who ever lived". He also added that they played a game called Corks, a simplified version of strip poker.

Neysa McMein met Jack Baragwanath at a party at the home of Irene Castle. Baragwanath later recalled: "The party turned out to be great fun. There was dancing and a good deal of singing around the piano which was played by a girl - an artist, I was told - whose name was Neysa McMein. She was so striking that I could hardly take my eyes off her. Fairly tall, with a fine figure, she had a face whose high cheek-bones, greenish eyes, and heavy, dark lashes and eyebrows would have commanded attention and admiration anywhere.... She wasn't a beauty, she was just beautiful. She asked me to drop in at her studio the following Saturday afternoon."

In his autobiography, A Good Time was Had (1962), Baragwanath described the meeting in her studio: "I went to Neysa's studio that Saturday afternoon and was welcomed pleasantly but, I thought, rather blankly. Obviously, she had forgotten where she had met me but sensed that in some misguided moment she must have invited me. She grinned and casually waved an introduction to her other guests, none of whom even looked up, then she went back to her easel where she was putting the final touches to a pretty-girl cover job in pastels. She concentrated without any regard to the noise in the room, which was roughly that of a busy steel plant. There were two pianos, back-to-back, manned by two vigorous young men, one of whom turned out to be Arthur Samuels, a young advertising man, and the other Jascha Heifetz. Over in the corner, at a rickety table, four men, including Heywood Broun and George Kaufman, were playing poker, quite oblivious to the enveloping racket. On and around a sway-backed sofa were several aspiring actresses screaming at each other above the clamor in a frantic effort to convey their egocentric thoughts. Other and even more voluble guests arrived to add to the decibels of uproar. Neysa just stood at the easel through all this, her hair in disorder, her face and faded blue smock streaked and smudged with pastels, easily translating the tranquil beauty of her model into colored chalk on a sandboard."

A former mining engineer, according to Brian Gallagher Baragwanath was: "Six feet tall, broad-shouldered and lean, he wore his dark hair slicked back and sported a thin mustache. His close resemblance to some of the dashing male leads of the period's films could not be missed." After a bad start the relationship approved and they eventually got married in 1923. A daughter, Joan, was born the following year.

Like their friends, Ruth Hale and Heywood Broun and Jane Grant and Harold Ross, Neysa and John had an open marriage. Neysa had a long-term relationship with the Broadway director George Abbott and had affairs with several other high profile men, including Robert Benchley. Her biographer points out that although she was relatively discreet she acquired a considerable reputation for promiscuous behaviour. Her friend, Samuel Hopkins Adams, described her as: "Beautiful, grave, and slightly soiled... one hastens to add, is to be taken in a purely superficial sense as applicable to the illustrator's paint-smeared smock and fingers." Alexander Woollcott added: "She (Neysa) is beautiful, grave and slightly soiled."

Beatrice Hinkle wrote in The Nation about the changes that were taking place concerning human relationships: "The upheaval in sex morals particularly affects the feminine world and by many people can scarcely be considered calmly enough for an examination... It can be said that in the general disintegration of old standards, women are the active agents in the field of sexual morality and men the passive, almost bewildered accessories to the overthrow of their long and firmly organized control of women's sexual conduct.... Women are for the first time demanding to live the forbidden experience directly and draw conclusions on this basis."

Brian Gallagher, the author of Anything Goes: The Jazz Age of Neysa McMein and her Extravagant Circle of Friends (1987), has pointed out that Neysa had close relationships with "homosexuals or neuters" like Alexander Woollcott. "Neysa tended to maneuver round an actual admission of her sexual liaisons: she would hint much but confirm little... Neysa spent a fair amount of time with men who could be no more than good friends. Still, it is clear that both were able to acknowledge, tolerate, and absorb into their marriage a degree of infidelity."

Another lover was Ring Lardner. His biographer, Jonathan Yardley, argues in Ring: A Biography of Ring Lardner (1977): "Ring Lardner was willing to wink at peculiarities of behavior in some women he liked - Neysa McMein, a well-known artist of the time, was widely rumored to have had many prominent lovers - so long as they brought style, wit and class to the friendship."

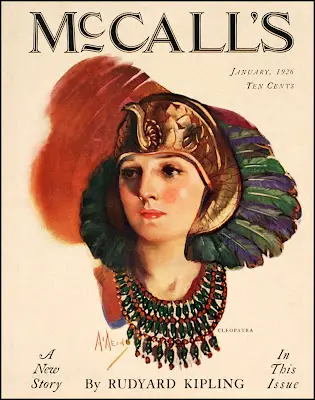

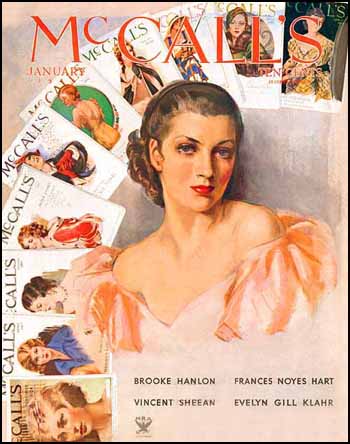

Neysa McMein was a highly successful artist and between 1923 and 1937 she created all of the covers of McCall's Magazine. In 1932-1933 she was also the magazine's film reviewer. McMein also produced illustrations for Collier's Magazine, McClure's Magazine, Liberty Magazine, Woman's Home Companion and Photoplay. She was also in great demand as the creator of advertising posters. McMein once commented that she could not draw even an egg without a model. McMein admitted that she only had a "facile talent, remarkable only for its fine sense of colour".

Marc Connelly believed she underestimated her talent: "Her fortune sprang up like a beautiful flower and at one time you couldn't pick up a magazine or see a magazine on a newsstand... that didn't have one of Neysa's pretty girls on the cover; the most popular illustrator, probably, the country ever saw." Jane Grant claimed that "beneath her apparent casualness" there was a "deep-seated desire for success".

Brian Gallagher pointed out that "McMein girl" became the most recognizable and the most distinctive, female magazine type since the "Gibson girl" of several decades earlier. "Neysa had, in her own fortunate and instinctive way, found the artistic means for making the most of her talents and for allowing her to create works so expressive of their period.... She was a model on which the young women of the times could style themselves.... While she was strikingly pretty, her beauty was at least of the possible type. And her smart, casual air was something young women could attain, even if they were not pretty."

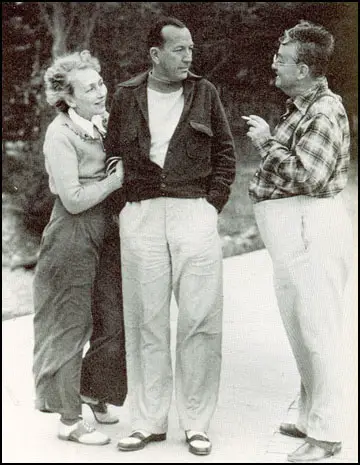

In 1925 Alexander Woollcott purchased most of Neshobe Island in Lake Bososeen. Other shareholders included Neysa McMein, Jack Baragwanath, Alice Duer Miller, Beatrice Kaufman, Marc Connelly, Raoul Fleischmann, Howard Dietz and Janet Flanner. Most weekends he invited friends to the island to play games. Vincent Sheean was a regular visitor to the island. He claimed that Dorothy Parker did not enjoy her time there: "She couldn't stand Alec and his goddamned games. We both drank, which Alec couldn't stand. We sat in a corner and drank whisky... Alec was simply furious. We were in disgrace. We were anathema. we ween't paying any attention to his witticisms and his goddamned games."

Joseph Hennessey, who ran the island for the visitors, later commented: "He ran the island like a benevolent monarchy, and he summoned both club members and other friends to appear at all seasons of the year; he turned the island into a crowded vacation ground where reservations must be made weeks in advance; the routine of life was completely remade to suit his wishes." Regular visitors included Dorothy Thompson, Rebecca West, Charles MacArthur, David Ogilvy, Harpo Marx, Lynn Fontanne, Alfred Lunt, Noël Coward, Laurence Olivier, Vivien Leigh and Ruth Gordon.

Jack Baragwanath later recalled that he never liked Alexander Woollcott: " Among all of Neysa's friends there was only one man I disliked: Alexander Woollcott. Unfortunately, he was one of Neysa's closest and oldest attachments and seemed to regard her as his personal property. I knew, too, that she was deeply fond of him, which made my problem much harder, for I imagined the consequences of the sort of open row which Alec often seemed bent on promoting. When he and I were alone he was disarmingly pleasant, but in a group he would sometimes go out of his way to make me feel small. I was no match for him at the kind of thrust and parry that was his forte, but after a while I found that if I could make him mad, he would drop his rapier and furiously attack with a heavy mace of anger, with which he would sometimes clumsily knock himself over the head. Then I would have him.... Close as Neysa and Alec were, and as much as he loved her, his uncontrollable tongue would get the better of him and he would say something so cruel and spiteful to her that she would refuse to see him for as long as six months at a time. And there were little incidents, not infrequent ones, when he would obviously try to hurt her."

Jack and Neysa also bought a home in Sands Point on the North Shore of Long Island. They loved entertaining friends such as Herbert Bayard Swope, Alice Duer Miller, Alexander Woollcott, Ruth Hale, Jane Grant, Charles MacArthur, Marc Connelly, George S. Kaufman, Beatrice Kaufman , Donald Ogden Stewart, George Abbott, George Gershwin, Ethel Barrymore and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Abbott claimed that Nesya was "the greatest party giver who ever lived". He also added that they played a game called Corks, a simplified version of strip poker.

Another close friend was Noël Coward. He recalled in his autobiography, Present Indicative (1937) that the relationship got off to a bad start: "I found several new friends, and together with them and some of my older ones I whirled through parties and trips to Harlem, and weekends in the country.... Among the new ones was Neysa McMein: beautiful, untidy, casual, and too difficult to know in a short month. I had actually met her during my first visit, and I think I found her rather tiresome. I was even more hasty in my judgments in those days than I am now, and as frequently inaccurate. I remembered having been taken to her studio a couple of times, where I had met a miscellaneous selection of models, journalists, actors and Vanderbilts, swimming round and in and out like rather puzzled fish in a dusty aquarium. Neysa paid little or no attention to anyone except when they arrived or left, when, with a sudden spurt of social conscience, she would ram a paint-brush into her mouth and shake hands with a kind of dishevelled politeness. I was too inexperienced and edgy then to appreciate properly her unique talent for living, but I can salute it now."

Ely Jacques Kahn, the author of The World of Swope (1965) has pointed out that McMein played croquet with Herbert Bayard Swope and his friends, Alice Duer Miller, Alexander Woollcott, George S. Kaufman, Beatrice Kaufman, Charles MacArthur, Robert E. Sherwood, Edna Ferber, Frank Sullivan, Marc Connelly, Jack Baragwanath, Averell Harriman, Harpo Marx, Raoul Fleischmann and Howard Dietz, on his garden lawn: "The croquet he played was a far cry from the juvenile garden variety, or back-lawn variety. In Swope's view, his kind of croquet combined, as he once put it, the thrills of tennis, the problems of golf, and the finesse of bridge. He added that the game attracted him because it was both vicious and benign." According to Kahn it was McMein who first suggested: "Let's play without any bounds at all." This enabled Swope to say: "It makes you want to cheat and kill... The game gives release to all the evil in you." Woollcott believed that McMein was the best player but Miller "brings to the game a certain low cunning." Woollcott wrote that the point of croquet was not merely to "excel your neighbour but to damage him."

Neysa McMein's contract with McCall's Magazine came to an end in April 1938. Changes in technology enabled magazines to be printed on four-colour machines. It was now possible to substitute much lower priced colour photographs for expensive cover sketches and McMein lost her job. McMein now concentrated on portrait painting. Among her subjects were Dorothy Parker, Warren G. Harding, Herbert Hoover, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Dorothy Thompson, Charlie Chaplin, Charles Evans Hughes, Ferdinand von Zeppelin, Anne Morrow Lindbergh, Janet Flanner, Katharine Cornell, Helen Hayes and Anatole France.

Unlike most of her friends, McMein was not very interested in politics. Most of her friends were strong supporters of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Her lover, George Abbott, claimed that she was "on the liberal side, but very, very vague". In 1940 she involved herself in political campaign of Wendell Willkie. Her biographer Brian Gallagher pointed out: "Willkie's liberal Republicanism and one world philosophy appealed rather neatly to her vague and sentimental political instincts. For the most part she personalized politics, favoring tolerant attitudes, because they reflected the politics of her origin."

In January 1942, while walking in her sleep, she had fallen downstairs and broken her back. When Alexander Woollcott heard the news he felt "as if someone were kneeling on my heart". Woollcott was also in poor health and McMein, who was recovering from a back and spine operation, which involved a piece of her hip being grafted to her spine, invited him to share a mutual convalescence at her home in Manhattan.

Samuel Hopkins Adams, the author of Smart Aleck, The Wit, World and Life of Alexander Woollcott (1976) has pointed out: "Neysa McMein's ability to attract visitors was a lifelong habit. Aleck's presence in her apartment compounded matters to the point where men and women were streaming in and out from early one morning until early the next... It proved to be too much for both of them" and Woollcott returned home.

Neysa McMein died of cancer in New York City on 12th May, 1949. John C. Baragwanath commented in his autobiography, A Good Time was Had (1962): "There could be no doubt that our marriage had been decidedly successful." He also admitted that it was a very unconventional relationship as it "was as much a deep friendship as a marriage".

© John Simkin, May 2013

Primary Sources

(1) Neysa McMein, interviewed on her return from her visit to the Western Front (1918)

Since I have lived through air bombing I never will be frightened at anything on earth. The terror of air raids cannot be imagined. They are heralded by the blowing of sirens and the ringing of church bells, and amid this din the lights are extinguished and then suddenly come the bombs, falling no one knows where. The noise they made is worse than that of the battles. The French immediately seek underground shelter - all over the cities places of safety are designated by signs - but the Americans prefer to stay above ground. When I was where there was a piano I rushed to it, and played as loudly as I could. The American boys in the hut would sit quietly in the dark. Once a building next to our hut was hit and totally demolished. Sometimes while riding on roads an enemy machine (a tank), which is always known by its peculiar trill, would come along and aim right at us. Trees were our only shelter.

(2) Marc Connelly, Voices Offstage (1968)

The world in which we moved was small, but it was churning with a dynamic group of young people who included Robert C. Benchley, Robert S. Sherwood, Ring Lardner, Dorothy Parker, Franklin. P. Adams, Heywood, Broun, Edna Ferber, Alice Duer Miller, Harold Ross, Jane Grant, Frank Sullivan, and Alexander Woollcott. We were together constantly. One of the habitual meeting places was the large studio of New York's preeminent magazine illustrator, Marjorie Moran McMein, of Muncie, Indiana. On the advice of a nurnerologist, she concocted a new first name when she became a student at the Chicago Art Institute. Neysa McMein. Neysa's studio on the northeast corner of Sixth Avenue and Fifty-seventh Street was crowded all day by friends who played games and chatted with their startlingly beautiful young hostess as one pretty girl model after another posed for the pastel head drawings that would soon delight the eyes of America on the covers of such periodicals as the Ladies' Home

Journal, Cosmopolitan, The American and The Saturday Evening Post.At times every newsstand sparkled with half a dozen of Neysa's beauties. Any afternoon at her studio you might encounter Jascha Heifetz, the violin prodigy, now grown up and beginning his adult career; Arthur Samuels, composer and wit who was soon to collaborate with Fritz Kreisler on the melodious operetta Apple Blossoms and a few years later became managing editor of The New Yorker; Janet Flanner, blazing with personality, later, over several decades, a journalistic legend as Genet, Paris correspondent of The New Yorker; and John Peter Toohey, a gentle free-lance press agent, deeply loved by everyone who ever crossed his path. Toohey wrote stories for The Saturday Evening Post and collaborated on a successful comedy entitled Swiftly. John was the acknowledged founder of the Thanatopsis Inside Straight Literary and Chowder Club and a target of many harmless practical jokes. One would also see Sally Farnham, the sculptress, whose studio was in the same building. Today one of her great works stands almost around the corner from her old workshop. It is the heroic equestrian statue of Simon Bolivar at the Sixth Avenue entrance to Central Park. Another habituee was the most photographed society beauty of that time, the beautiful Julia Hoyt. Among Neysa's noteworthy full-figure portraits in oil were those of Julia and Janet Flanner.

There was always a cluster of young actresses. Margalo and Ruth Gillmore, Winifred Lenihan, Tallulah Bankhead, Myra Hampton, and Lenore Ulric. Despite the near-bedlam about her, Neysa's eyes never left her work. At the end of a day and the completion of another delicately executed magazine cover, Neysa's smock and face would be smeared with chalk and paint. She would disappear and five minutes later rejoin us fresh as a flower, ready to listen, entertain, and be entertained. After five o'clock the big studio would be crowded with her cronies, many engaged in daily sessions of poker, crap, backgammon, and cribbage. Samuels or someone else would be at the piano.

(3) John Keats, You Might as Well Live: The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1971)

She (Dorothy Parker) had taken an apartment in a building on West Fifty-seventh Street where the beautiful and somewhat Bohemian artist Neysa McMein had a studio. Miss Mcmein was a familiar of the Round Table, and her studio was a nocturnal headquarters for the Algonquin group. But Dorothy had taken the apartment because it was convenient to this meeting place of all her friends, and not for the purpose of sleeping with any of them.

(4) Alexander Woollcott, Neysa McMein (1924)

Over at the piano Jascha Heifetz and Arthur Samuels may be trying to find out what four hands can do in the syncopation of a composition never thus desecrated before. Irving Berlin is encouraging them. Squatted uncomfortably around an ottoman, Franklin P. Adams, Marc Connelly and Dorothy Parker will be playing cold hands to see who will buy the dinner that evening. At the bookshelf Robert C. Benchley and Edna Ferber are amusing themselves vastly by thoughtfully autographing her set of Mark Twain for her. In the corner, some jet-bedecked dowager from a statelier milieu is taking it all in, immensely diverted. Chaplin, Alice Duer Miller or Wild Bill Donovan, Father Duffy or Mary Pickford - any or all of them may be there... If you loiter in Neysa McMein's studio, the world will drift in and out. Standing at the easel itself, oblivious of all the ructions, incredibly serene and intent on her work, is the artist herself. She is beautiful, grave and slightly soiled.

(5) Noël Coward, Present Indicative (1937)

I found several new friends, and together with them and some of my older ones I whirled through parties and trips to Harlem, and weekends in the country. There were the Janises, Eva Le Gallienne, Ethel Barrymore, the Kaufmans, Woollcott and many others. Among the new ones was Neysa McMein: beautiful, untidy, casual, and too difficult to know in a short month. I had actually met her during my first visit, and I think I found her rather tiresome. I was even more hasty in my judgments in those days than I am now, and as frequently inaccurate. I remembered having been taken to her studio a couple of times, where I had met a miscellaneous selection of models, journalists, actors and Vanderbilts, swimming round and in and out like rather puzzled fish in a dusty aquarium. Neysa paid little or no attention to anyone except when they arrived or left, when, with a sudden spurt of social conscience, she would ram a paint-brush into her mouth and shake hands with a kind of dishevelled politeness. I was too inexperienced and edgy then to appreciate properly her unique talent for living, but I can salute it now.

(6) Jack Baragwanath, A Good Time was Had ( 1962)

The party turned out to be great fun. There was dancing and a good deal of singing around the piano which was played by a girl-an artist, I was told-whose name was Neysa McMein. She was so striking that I could hardly take my eyes off her. Fairly tall, with a fine figure, she had a face whose high cheek-bones, greenish eyes, and heavy, dark lashes and eyebrows would have commanded attention and admiration anywhere. She had a tumbling mass of untidy, blond, I-can't-do-anything-with-it hair, and her dress was simply a dress. She wasn't a beauty, she was just beautiful. She asked me to drop in at her studio the following Saturday afternoon.

What now impresses me with that party of Irene Castle's was the number of young people there, roughly my age, who were to achieve great reputations in the arts - Bob Benchley, Marc Connelly, Sally Farnham, George Kaufman, Charlie MacArthur, Dorothy Parker, Bob Sherwood, Alec Woollcott, and several others. This group was an amazingly small nebula considering how many bright stars were to burst from it.

(7) Jack Baragwanath, A Good Time was Had ( 1962)

I went to Neysa's studio that Saturday afternoon and was welcomed pleasantly but, I thought, rather blankly. Obviously, she had forgotten where she had met me but sensed that in some misguided moment she must have invited me. She grinned and casually waved an introduction to her other guests, none of whom even looked up, then she went back to her easel where she was putting the final touches to a pretty-girl cover job in pastels. She concentrated without any regard to the noise in the room, which was roughly that of a busy steel plant. There were two pianos, back-to-back, manned by two vigorous young men, one of whom turned out to be Arthur Samuels, a young advertising man, and the other Jascha Heifetz. Over in the corner, at a rickety table, four men, including Heywood Broun and George Kaufman, were playing poker, quite oblivious to the enveloping racket. On and around a sway-backed sofa were several aspiring actresses screaming at each other above the clamor in a frantic effort to convey their egocentric thoughts. Other and even more voluble guests arrived to add to the decibels of uproar.

Neysa just stood at the easel through all this, her hair in disorder, her face and faded blue smock streaked and smudged with pastels, easily translating the tranquil beauty of her model into colored chalk on a sandboard. I sat there quietly and unnoticed, thinking what a damn fool I had been to trade the pleasure of Grace's company for this circus, but I treated myself to an occasional smile at Grace's conception of the dangers of Neysa's jungle studio.

(8) Beatrice Hinkle, The Nation (19th November 1924)

The upheaval in sex morals particularly affects the feminine world and by many people can scarcely be considered calmly enough for an examination... It can be said that in the general disintegration of old standards, women are the active agents in the field of sexual morality and men the passive, almost bewildered accessories to the overthrow of their long and firmly organized control of women's sexual conduct.... Women are for the first time demanding to live the forbidden experience directly and draw conclusions on this basis.

(9) Anita Loos, A Girl Like I (1966)

Neysa was a magnificent young creature, a Brünnhilde with a classic face, tawny hair that scorned a brush or comb, and a style of dress for which her inspiration could only have been a grabbag. But all New York knew she was the heroine of a succession of romances with extremely prominent men. When Neysa invited me to her studio I accepted, but I confess to being critical of her; to me Neysa's unkempt appearance seemed phony and even a little conceited; it was if Cinderella had purposely gone to the ball in rags, knowing they'd make her all the more a sensation.

(10) Samuel Hopkins Adams, Alexander Woollcott: His Life and His World (1946)

Neysa McMein was a reigning toast of the Algonquin Sophisticates and the object of unrequited passion to several. Christened Marjorie Moran McMein, she had changed her name at the instance of a numerological sibyl who promised her wealth, success, and happiness under a more suitable formula... Woollcott, now cured of his disappointment over Jane Grant, had joined the court of Miss McMein's devotees, where the others never saw any occasion to be jealous of him... Beautiful, grave, and slightly soiled... one hastens to add, is to be taken in a purely superficial sense as applicable to the illustrator's paint-smeared smock and fingers.

(11) Brian Gallagher, Anything Goes: The Jazz Age of Neysa McMein and her Extravagant Circle of Friends (1987)

Neysa's peculiar genius as a hostess, as many have attested, was that she most gloriously did not preside. Any guest who showed up in daylight hours would get the same democratic greeting: Neysa, disheveled, her hair and smock streaked by the drizzle of the pastel dust, would emerge enthusiastically from the chaos surrounding her easel, give the visitor a rousing, sticky handshake, and entrust his or her amusement to whatever group was already there and making merry. Instantly, she returned to her work-and kept at it steadily despite the convivial temptations near at hand and a noise level one visitor estimated as "roughly that of a busy steel plant." If a visitor left while she was still sketching, she would pause only long enough to offer another hearty handshake, thank the guest profusely for coming, and urge a return visit. Neysa's nonchalant stance as a hostess offended a few, and at first it puzzled the more direct Jack Baragwanath, but it captivated a great many more. On any given afternoon between 1920 and 1926 a fair share of the talented, witty, and interesting people in New York could be found in Neysa McMein's studio.

Perched on her stool, her eyes fixed on her drawing, and looking the more lovely for her physical disarray and air of detachment, Neysa very much created the impression of, in Helen Hayes's apt metaphor, "a tortoise shell cat who had gone to art school." No doubt there was something uncannily feline about her - as if at her bidding the noisy, surrounding world could impinge on her not at all, except at those moments when she would pause from her work to toss a casual remark its way. Anais Nin, who, as a young model, posed for Neysa, was one of several persons who found the blasé attitude Neysa exercised in her studio, her ultimate air of indifference, more a cause of vexation than charm.