Algonquin Round Table

Robert E. Sherwood, Dorothy Parker and Robert Benchley all worked at Vanity Fair during the First World War. They began taking lunch together in the dining room at the Algonquin Hotel. Sherwood was six feet eight inches tall and Benchley was around six feet tall, Parker, who was five feet four inches, once commented that when she, Sherwood and Benchley walked down the street together, they looked like "a walking pipe organ."

According to Harriet Hyman Alonso , the author of Robert E. Sherwood The Playwright in Peace and War (2007): "John Peter Toohey, a theater publicist, and Murdock Pemberton, a press agent, decided to throw a mock "welcome home from the war" celebration for the egotistical, sharp-tongued columnist Alexander Woollcott. The idea was really for theater journalists to roast Woollcott in revenge for his continual self-promotion and his refusal to boost the careers of potential rising stars on Broadway. On the designated day, the Algonquin dining room was festooned with banners. On each table was a program which misspelled Woollcott's name and poked fun at the fact that he and fellow writers Franklin Pierce Adams (F.P.A.) and Harold Ross had sat out the war in Paris as staff members of the army's weekly newspaper, the Stars and Stripes, which Bob had read in the trenches. But it is difficult to embarrass someone who thinks well of himself, and Woollcott beamed at all the attention he received. The guests enjoyed themselves so much that John Toohey suggested they meet again, and so the custom was born that a group of regulars would lunch together every day at the Algonquin Hotel."

Howard Teichmann has pointed out: "That the Algonquin should have been brought to such prominence by press agents was no more surprising than the fact that Broadway was beginning to make more and more use of those ever-ready friends of the Fourth Estate. Actually, the Algonquin was the first of many restaurants to gain postwar attention through the efforts of press agents." Murdock Pemberton later recalled that he owner of the hotel, Frank Case, did what he could to encourage this gathering: "From then on we met there nearly every day, sitting in the south-west corner of the room. If more than four or six came, tables could be slid along to take care of the newcomers. We sat in that corner for a good many months... Frank Case, always astute, moved us over to a round table in the middle of the room and supplied free hors d'oeuvre. The table grew mainly because we then had common interests. We were all of the theatre or allied trades." Case admitted that he moved them to a central spot at a round table in the Rose Room, so others could watch them enjoy each other's company.

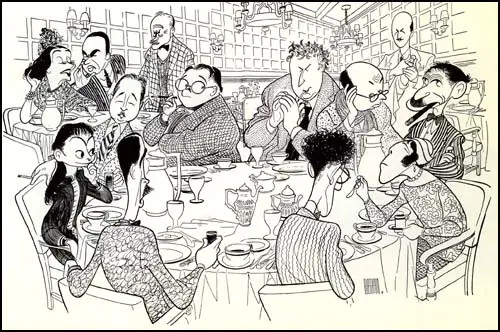

The people who attended these lunches included Robert E. Sherwood, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Alexander Woollcott, Heywood Broun, Harold Ross, Donald Ogden Stewart, Edna Ferber, Ruth Hale, Franklin Pierce Adams, Jane Grant, Neysa McMein, Alice Duer Miller, Charles MacArthur, Marc Connelly, George S. Kaufman, Beatrice Kaufman , Frank Crowninshield, Ben Hecht, Frank Sullivan, Jack Baragwanath, John Peter Toohey, Lynn Fontanne, Alfred Lunt and Ina Claire. This group eventually became known as the Algonquin Round Table.

According to Brian Gallagher, the author of Anything Goes: The Jazz Age of Neysa McMein and her Extravagant Circle of Friends (1987) "the Algonquin group was at the center of a social revolution". Gallagher quotes Alice Duer Miller, as saying the First World War was partly responsible for the creation of the Algonquin Round Table: "Alice Duer Miller, the eldest member of the Round Table set, noted, the war broke up the old social crowds in New York and allowed new ones to form, and she threw her patrician lot in with a younger group of writers and wits. New kinds of elites were forming: often less rich and less grand than the older elites, but also more numerous and more varied. Over the next two decades the members of the Algonquin group would go far, usually under self-propulsion, on the group's reputation as an intellectual elite."

The group played games while they were at the hotel. One of the most popular was "I can give you a sentence". This involved each member taking a multi syllabic word and turning it into a pun within ten seconds. Dorothy Parker was the best at this game. For "horticulture" she came up with, "You can lead a whore to culture, but you can't make her think." Another contribution was "The penis is mightier than the sword." They also played other guessing games such as "Murder" and "Twenty Questions". A fellow member, Alexander Woollcott, called Parker "a combination of Little Nell and Lady Macbeth." Arthur Krock, who worked for the New York Times, commented that "their wit was on perpetual display."

Edna Ferber wrote about her membership of the group in her book, A Peculiar Treasure (1939): "The contention was that this gifted group engaged in a log-rolling; that they gave one another good notices, praise-filled reviews and the like. I can't imagine how any belief so erroneous ever was born. Far from boosting one another they actually were merciless if they disapproved. I never have encountered a more hard-bitten crew. But if they liked what you had done they did say so, publicly and wholeheartedly. Their standards were high, their vocabulary fluent, fresh, astringent and very, very tough. Theirs was a tonic influence, one on the other, and all on the world of American letters. The people they could not and would not stand were the bores, hypocrites, sentimentalists, and the socially pretentious. They were ruthless towards charlatans, towards the pompous and the mentally and artistically dishonest. Casual, incisive, they had a terrible integrity about their work and a boundless ambition."

The literary critic, Edmund Wilson, was not so impressed with the group: "I was sometimes invited to join them, but I did not find them particularly interesting. They all came from the suburbs and provinces, and a sort of tone was set - mainly by Benchley, I think - deriving from a provincial upbringing of people who had been taught a certain kind of gentility, who had played the same games and who had read the same children's books - all of which they were now able to mock from a level of New York sophistication."

Marc Connelly, was an important figure in the early days of the group: "We all lived rather excitedly and passionately. In those days, everything was of vast importance or only worthy of quick dismissal. We accepted each other - the whole crowd of us. I suppose there was a corps of about twenty or so who were intimate. We all ate our meals together, and lived in a very happy microcosm.... We all shared one another's love for bright talk, contempt for banality, and the dedication to the use of whatever talents we had to their best employment." Another regular member was George S. Kaufman. Connelly and Kaufman wrote five successful comedies, Dulcy (1921), To the Ladies (1922), Merton of the Movies (1922), The Deep Tangled Wildwood (1923) and Beggar on Horseback (1924).

Samuel Hopkins Adams, the author of Alexander Woollcott: His Life and His World (1946), has argued: "The Algonquin profited mightily by the literary atmosphere, and Frank Case evinced his gratitude by fitting out a workroom where Broun could hammer out his copy and Benchley could change into the dinner coat which he ceremonially wore to all openings. Woollcott and Franklin Pierce Adams enjoyed transient rights to these quarters. Later Case set aside a poker room for the whole membership." The poker players included Heywood Broun, Alexander Woollcott, Herbert Bayard Swope, Robert Benchley, George S. Kaufman, Harold Ross, Deems Taylor, Laurence Stallings, Harpo Marx, Jerome Kern and Prince Antoine Bibesco.

On one occasion, Woollcott lost four thousand dollars in an evening, and protested: "My doctor says it's bad for my nerves to lose so much." It was also claimed that Harpo Marx "won thirty thousand dollars between dinner and dawn". Howard Teichmann, the author of George S. Kaufman: An Intimate Portrait (1972) has argued that Broun, Adams, Benchley, Ross and Woollcott were all inferior poker players, Swope and Marx were rated as "pretty good" and Kaufmann was "the best honest poker player in town."

On 30th April 1922, the Algonquin Round Tablers produced their own one-night vaudeville review, No Siree!: An Anonymous Entertainment by the Vicious Circle of the Hotel Algonquin . It was opened by Heywood Broun who appeared before the curtain "looking much like a dancing bear who had escaped from his trainer". He was followed by a monologue by Robert Benchley, entitled The Treasurer's Report . Marc Connelly and George S. Kaufman contributed a three-act mini-play, Big Casino Is Little Casino, that featured Robert E. Sherwood. The show also included several musical numbers, some written by Irving Berlin. One of the most loved aspects of the show was the Dorothy Parker penned musical numbers that were sang by Tallulah Bankhead, Helen Hayes, June Walker and Mary Brandon.

New York Times assigned the actress, Laurette Taylor, to review the show. She suggested that the lot of them to give up any theatrical ambitions, but if they persisted in placing themselves on public view, "I would advise a course of voice culture for Marc Connelly, a new vest and pants for Heywood Broun, a course with Yvette Guilbert for Alexander Woollcott... I suppose there must have been some suppressed indignation in my heart to see the critics maligning my stage, just as there will be at my daring to sit and judge as a critic."

John Keats, the author of You Might as Well Live: Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1975) has argued that Heywood Broun, who was popular columnist, with national syndication, greatly helped in spreading the influence of the Algonquin Round Table. "His friends thought coloured Mr. Broun's own thinking. When he therefore spoke to his several million readers, Mr. Broun was not giving them just an Eastern seaboard point of view, but a specifically Round Table point of view... The Algonquinites could cause to be published, and could comment on, such new writing as, for example, that of the Paris group, and thereby help to create a climate in which it would find acceptance."

Marc Connelly claims that the group spent a lot of time at the studio of Neysa McMein. "The world in which we moved was small, but it was churning with a dynamic group of young people who included Robert C. Benchley, Robert S. Sherwood, Ring Lardner, Dorothy Parker, Franklin. P. Adams, Heywood, Broun, Edna Ferber, Alice Duer Miller, Harold Ross, Jane Grant, Frank Sullivan, and Alexander Woollcott. We were together constantly. One of the habitual meeting places was the large studio of New York's preeminent magazine illustrator, Marjorie Moran McMein, of Muncie, Indiana. On the advice of a nurnerologist, she concocted a new first name when she became a student at the Chicago Art Institute. Neysa McMein. Neysa's studio on the northeast corner of Sixth Avenue and Fifty-seventh Street was crowded all day by friends who played games and chatted with their startlingly beautiful young hostess as one pretty girl model after another posed for the pastel head drawings that would soon delight the eyes of America on the covers of such periodicals as the Ladies' Home Journal, Cosmopolitan, The American and The Saturday Evening Post."

Some members of the Algonquin Round Table began to complain about the nastiness of some of the humour as it gained the reputation for being the "Vicious Circle". Donald Ogden Stewart commented: "It wasn't much fun to go there, with everybody on stage. Everybody was waiting his chance to say the bright remark so that it would be in Franklin Pierce Adams' column the next day... it wasn't friendly... Woollcott, for instance, did some awfully nice things for me. There was a terrible sentimental streak in Alec, but at the same time, there was a streak of hate that was malicious."

Anita Loos commented that on arriving in New York City: "I soon found out that the most literary envirament in New York is the Algonquin Hotel, where all the literary geniuses eat their luncheon. Because every literary genius who eats his luncheon at the Algonquin Hotel is always writing that that is the place where all the great literary geniuses eat their luncheon."

Dorothy Parker eventually became disillusioned with the Algonquin Round Table: "The only group I have ever been affiliated with is that not especially brave little band that hid its nakedness of heart and mind under the out-of-date garment of a sense of humor... I know that ridicule may be a shield, but it is not a weapon." Parker eventually left because of a disagreement over the Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco case: "Those people at the Round Table didn't know a bloody thing. They thought we were fools to go up and demonstrate for Sacco and Vanzetti." She claimed they were ignorant because "they didn't know and they just didn't think about anything but the theater." Parker added: "At first I was in awe of them because they were being published. But then I came to realize I wasn't hearing anything very stimulating. The one man of real stature who ever went there was Heywood Broun. He and Robert Benchley were the only people who took any cognizance of the world around them. George Kaufman was a nuisance and rather disagreeable. Harold Ross, the New Yorker editor, was a complete lunatic; I suppose he was a good editor, but his ignorance was profound."

Richard O'Connor, the author of Heywood Broun: A Biography (1975) argued that the Algonquin Round Table went into decline at the beginning of the 1930s. "All those satirical darts hurled around the table were bound, sooner or later, to leave their marks on the more sensitive spirits. Some members, as the joy went out of the twenties and curdled into the despair of the thirties, thought they should occupy themselves with something more serious than chitchat. Others had moved to Hollywood or had been dislodged from their corner in the marketplace; failure was never viewed with sympathy by members of the Round Table." Those who went to Hollywood included Robert E. Sherwood, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Donald Ogden Stewart, Charles MacArthur and Ben Hecht.

Heywood Broun stopped going to the Algonquin Hotel after complaining that some members of the Round Table, including George S. Kaufman and Ina Claire, had undermined a strike by filling in as waiters in the dining room. Margaret Chase Harriman, the author of The Vicious Circle The Story of the Algonquin Round Table (1951), has pointed out: "The emotional lives of many of them had grown so complex as to interfere with their gags... Perhaps it was politics, and a broadening sense of public issues, that helped to break up the Round Table... As the small, independent worlds we all used to live in gradually expanded and fused into One World with its one vast headache, there was no longer any room for cozy little sheltered cliques of specialists... The day of the purely literary or artistic group was over, and so was the small, perfect democracy of the Algonquin Round Table."

Primary Sources

(1) Harriet Hyman Alonso, Robert E. Sherwood The Playwright in Peace and War (2007)

The place where Parker, Benchley, and Bob lunched together each workday thereafter was the dining room at the Algonquin Hotel. Located close to their office, the hotel had been founded in 1902 as a temperance establishment called the Puritan, but in 1919 its manager, Frank Case, renamed it the Algonquin in honor of the Native Americans who had originally lived in the area. Unfortunately for Case, the name change did not alter the hotel's temperance history, for in that same year the nation adopted the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution, making the production, sale, and transportation of alcoholic beverages illegal in the United States. Initially, the three writers dined alone on hors d'oeuvres or scrambled eggs and coffee, the only items they could afford on their meager Vanity Fair salaries. Soon after, however, an event took place at the Algonquin Hotel which changed all their lives, especially Bob's. John Peter Toohey, a theater publicist, and Murdock Pemberton, a press agent, decided to throw a mock "welcome home from the war" celebration for the egotistical, sharp-tongued columnist Alexander Woollcott. The idea was really for theater journalists to roast Woollcott in revenge for his continual self-promotion and his refusal to boost the careers of potential rising stars on Broadway. On the designated day, the Algonquin dining room was festooned with banners. On each table was a program which misspelled Woollcott's name and poked fun at the fact that he and fellow writers Franklin Pierce Adams (F.P.A.) and Harold Ross had sat out the war in Paris as staff members of the army's weekly newspaper, the Stars and Stripes, which Bob had read in the trenches. But it is difficult to embarrass someone who thinks well of himself, and Woollcott beamed at all the attention he received.

The guests enjoyed themselves so much that John Toohey suggested they meet again, and so the custom was born that a group of regulars would lunch together every day at the Algonquin Hotel. In addition to Bob, Benchley, Parker, Woollcott, F.P.A, and Ross, others who joined as the weeks passed included the journalist Heywood Broun, the play-writing team of Marc Connelly and George S. Kaufman, the playwright Howard Dietz, and authors Edna Ferber and Alice Duer Miller. Once in a while the writer Ring Lardner or Bob's songwriter hero Irving Berlin would drop by. Aspiring actresses Helen Hayes, Peggy Wood, Tallulah Bankhead, and Ruth Gordon sat in from time to time, as did innumerable young showgirls and chorus boys hoping to latch onto either a rising star or one already in the magic circle of fame on Broadway or in Hollywood. Mary Brandon was one such young woman whose rising star became Bob Sherwood. For Frank Case, the opportunity to cultivate a group of journalists, writers, and actors who might bring more customers to the hotel was a godsend, and he decided to make them a feature of his establishment. After several months of catering to them at a long side table, he moved the group to a central spot at a round table in the Rose Room, where tourists and other diners could stare and pretend to be sharing in the making of cultural history along with the Algonquin Round Table.

(2) Edna Ferber, A Peculiar Treasure (1939)

Outsiders took a kind of resentful dislike to the group. They called them the Algonquin crowd. I was astonished to find myself included in this designation. The contention was that this gifted group engaged in a log-rolling; that they gave one another good notices, praise-filled reviews and the like. I can't imagine how any belief so erroneous ever was born. Far from boosting one another they actually were merciless if they disapproved. I never have encountered a more hard-bitten crew. But if they liked what you had done they did say so, publicly and wholeheartedly. Their standards were high, their vocabulary fluent, fresh, astringent and very, very tough. Theirs was a tonic influence, one on the other, and all on the world of American letters. The people they could not and would not stand were the bores, hypocrites, sentimentalists, and the socially pretentious. They were ruthless towards charlatans, towards the pompous and the mentally and artistically dishonest. Casual, incisive, they had a terrible integrity about their work and a boundless ambition.

(3) Margaret Chase Harriman, The Vicious Circle The Story of the Algonquin Round Table (1951)

The emotional lives of many of them had grown so complex as to interfere with their gags... Perhaps it was politics, and a broadening sense of public issues, that helped to break up the Round Table... As the small, independent worlds we all used to live in gradually expanded and fused into One World with its one vast headache, there was no longer any room for cozy little sheltered cliques of specialists... The day of the purely literary or artistic group was over, and so was the small, perfect democracy of the Algonquin Round Table.

(4) Marc Connelly, Voices Offstage (1968)

The world in which we moved was small, but it was churning with a dynamic group of young people who included Robert C. Benchley, Robert S. Sherwood, Ring Lardner, Dorothy Parker, Franklin. P. Adams, Heywood, Broun, Edna Ferber, Alice Duer Miller, Harold Ross, Jane Grant, Frank Sullivan, and Alexander Woollcott. We were together constantly. One of the habitual meeting places was the large studio of New York's preeminent magazine illustrator, Marjorie Moran McMein, of Muncie, Indiana. On the advice of a nurnerologist, she concocted a new first name when she became a student at the Chicago Art Institute. Neysa McMein. Neysa's studio on the northeast corner of Sixth Avenue and Fifty-seventh Street was crowded all day by friends who played games and chatted with their startlingly beautiful young hostess as one pretty girl model after another posed for the pastel head drawings that would soon delight the eyes of America on the covers of such periodicals as the Ladies' Home Journal, Cosmopolitan, The American and The Saturday Evening Post.

At times every newsstand sparkled with half a dozen of Neysa's beauties. Any afternoon at her studio you might encounter Jascha Heifetz, the violin prodigy, now grown up and beginning his adult career; Arthur Samuels, composer and wit who was soon to collaborate with Fritz Kreisler on the melodious operetta Apple Blossoms and a few years later became managing editor of The New Yorker; Janet Flanner, blazing with personality, later, over several decades, a journalistic legend as Genet, Paris correspondent of The New Yorker; and John Peter Toohey, a gentle free-lance press agent, deeply loved by everyone who ever crossed his path. Toohey wrote stories for The Saturday Evening Post and collaborated on a successful comedy entitled Swiftly. John was the acknowledged founder of the Thanatopsis Inside Straight Literary and Chowder Club and a target of many harmless practical jokes. One would also see Sally Farnham, the sculptress, whose studio was in the same building. Today one of her great works stands almost around the corner from her old workshop. It is the heroic equestrian statue of Simon Bolivar at the Sixth Avenue entrance to Central Park. Another habituee was the most photographed society beauty of that time, the beautiful Julia Hoyt. Among Neysa's noteworthy full-figure portraits in oil were those of Julia and Janet Flanner.

(5) Edmund Wilson, The Twenties: From Notebooks and Diaries of the Period (1975)

I was sometimes invited to join them, but I did not find them particularly interesting. They all came from the suburbs and provinces, and a sort of tone was set - mainly by Benchley, I think - deriving from a provincial upbringing of people who had been taught a certain kind of gentility, who had played the same games and who had read the same children's books - all of which they were now able to mock from a level of New York sophistication.

© John Simkin, March 2013