Jack Baragwanath

Baragwanath studied geology and engineering at Columbia University (1906-1910). "During my last term, I took a course in archaeology under Professor Marshall Saville. I was fascinated by his lectures on the pre-Colombian peoples of Mexico, Central America, and the West Coast of South America. Near the close of the course, Saville asked me whether I would like to join an expedition to Ecuador sponsored by a gentleman named George Heye. He was leaving in about a month, he said, with a small party to study the pre-Incan civilization of that then remote country. He needed a geologist. Would I go for six months at a salary of twenty-five dollars a month and expenses."

When the expedition came to an end in August 1910 Baragwanath told Marshall Howatd Saville that he wished to stay in Ecuador. "I began to toy with the idea of becoming not only a geologist but a mining engineer. I had felt the terrific excitement of mining, of creating new wealth by digging ore from the ground. I had seen many men blasting out fortunes for themselves. I had already taken courses in the theory of mining, a lot of chemistry, surveying, assaying, mapping, and even a course in mining camp hygiene. Yes, I would be a mining engineer, leaning particularly on geology."

Baragwanath eventually got a job in a gold mine in Portovelo. "My first job was night-shift boss in the cyanide plant, a place full of vats, pipes, and zinc-boxes where the ground-up ore, after leaving the stamp mill, was leached in a highly poisonous solution of sodium cyanide, and the gold that was thus dissolved was deposited as a black slime on zinc shavings. The plant was a silent, eerie area, an Avernus where nothing moved but bats and big moths. My only duty was to turn certain valves at widely spaced intervals. The rest of the twelve-hour stretch I spent fighting to stay awake. In desperation I began to collect the moths that flocked, in large numbers and great variety and beauty, around two bright lights. If I had stayed there long enough, I would have become either an accomplished lepidopterist or a manic-depressive. But before long they must have recognized my technical genius for they transferred me to the Engineering Department."

This involved spending a lot of time underground: " J. Ward Williams... taught me the technique of mining wide and narrow quartz veins, driving drifts and cross-cuts, running raises, and sinking shafts. He made me learn to timber, lay track and hang pipe, to point blast-holes and how to space them. I was made dynamiter for one awful period during which, with one assistant, I had to load and shoot all the drill-holes in every stope at the end of each shift. Night after night I would stagger home with a 'powder-headache' so severe that no aspirin, Anacin, or Bufferin could have given me any relief even had such compounds been available. I am one of those unfortunates who are allergic to nitroglycerin."

On 28th January, 1912, a group of pro-Catholic soldiers killed recently imprisoned President Eloy Alfaro. "A mob had broken into his dungeon and dragged the old gentleman out. In the street the mob had tied ropes to his arms and legs and literally pulled him apart... Down in Guayaquil the crowd had beheaded a general of the Alfaristas and publicly burned his body in the main square. After this, they had put his head in a kerosene tin and sent it to his wife in Quito." Baragwanath, fearing for his own life, decided to return home.

A few months later Baragwanath obtained work with Morococha Mining Company in Peru. "My salary was $3,000 a year, most of it clear, as there were no expenses to speak of... I was soon made General Mine Captain, in charge of all the mines." By 1915 he was General Manager of the "whole Cerro de Pasco enterprise". He recorded in his autobiography, A Good Time was Had (1962): "The next four years I spent in exploring mine possibilities throughout the length and breadth in Peru, principally silver, copper, and lead mines."

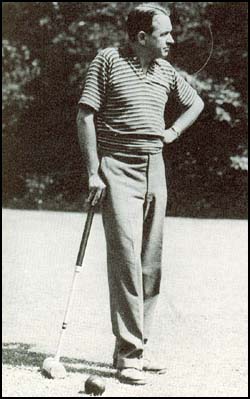

In October, 1919, Baragwanath established his own company in New York City. This mainly involved advising companies such as the Ludlum Steel Company. During this period he developed a reputation as a playboy. Women found Baragwanath very attractive and was known as "Handsome Jack". According to Brian Gallagher he was: "Six feet tall, broad-shouldered and lean, he wore his dark hair slicked back and sported a thin mustache. His close resemblance to some of the dashing male leads of the period's films could not be missed."

Baragwanath met the artist, Neysa McMein, at a party at the home of Irene Castle. Baragwanath later recalled: "The party turned out to be great fun. There was dancing and a good deal of singing around the piano which was played by a girl - an artist, I was told - whose name was Neysa McMein. She was so striking that I could hardly take my eyes off her. Fairly tall, with a fine figure, she had a face whose high cheek-bones, greenish eyes, and heavy, dark lashes and eyebrows would have commanded attention and admiration anywhere.... She wasn't a beauty, she was just beautiful. She asked me to drop in at her studio the following Saturday afternoon."

McMein was considered to be one of the most attractive women living in New York City. The writer, Marc Connelly claimed: "Neysa couldn't have been more popular. She couldn't have been lovelier. Everybody loved her. She was perfectly beautiful, a tall Amazonian sort of person, handsome as could be." Harpo Marx described her as "the sexiest gal in town" and admitted that "the biggest love affair in New York City was between me - along with two dozen other guys - and Neysa McMein."

In his autobiography, A Good Time was Had (1962), Baragwanath described the meeting in her studio: "I went to Neysa's studio that Saturday afternoon and was welcomed pleasantly but, I thought, rather blankly. Obviously, she had forgotten where she had met me but sensed that in some misguided moment she must have invited me. She grinned and casually waved an introduction to her other guests, none of whom even looked up, then she went back to her easel where she was putting the final touches to a pretty-girl cover job in pastels. She concentrated without any regard to the noise in the room, which was roughly that of a busy steel plant. There were two pianos, back-to-back, manned by two vigorous young men, one of whom turned out to be Arthur Samuels, a young advertising man, and the other Jascha Heifetz. Over in the corner, at a rickety table, four men, including Heywood Broun and George Kaufman, were playing poker, quite oblivious to the enveloping racket. On and around a sway-backed sofa were several aspiring actresses screaming at each other above the clamor in a frantic effort to convey their egocentric thoughts. Other and even more voluble guests arrived to add to the decibels of uproar. Neysa just stood at the easel through all this, her hair in disorder, her face and faded blue smock streaked and smudged with pastels, easily translating the tranquil beauty of her model into colored chalk on a sandboard."

Marc Connelly claimed: "Neysa couldn't have been more popular. She couldn't have been lovelier. Everybody loved her. She was perfectly beautiful, a tall Amazonian sort of person, handsome as could be." Harpo Marx described her as "the sexiest gal in town" and admitted that "the biggest love affair in New York City was between me - along with two dozen other guys - and Neysa McMein."

Baragwanath's relationship gradually improved and they married in 1923. A daughter, Joan, was born the following year. Like their friends, Ruth Hale and Heywood Broun and Jane Grant and Harold Ross, Neysa and John had an open marriage. Neysa had a long-term relationship with the Broadway director George Abbott and had affairs with several other high profile men, including Robert Benchley. Her biographer points out that although she was relatively discreet she acquired a considerable reputation for promiscuous behaviour. Her friend, Samuel Hopkins Adams, described her as: "Beautiful, grave, and slightly soiled... one hastens to add, is to be taken in a purely superficial sense as applicable to the illustrator's paint-smeared smock and fingers."

Brian Gallagher, the author of Anything Goes: The Jazz Age of Neysa McMein and her Extravagant Circle of Friends (1987), has pointed out that Neysa had close relationships with "homosexuals or neuters" like Alexander Woollcott. "Neysa tended to maneuver round an actual admission of her sexual liaisons: she would hint much but confirm little... Neysa spent a fair amount of time with men who could be no more than good friends. Still, it is clear that both were able to acknowledge, tolerate, and absorb into their marriage a degree of infidelity."

Another of Neysa's lovers was Ring Lardner. His biographer, Jonathan Yardley, argues in Ring: A Biography of Ring Lardner (1977): "Ring Lardner was willing to wink at peculiarities of behavior in some women he liked - Neysa McMein, a well-known artist of the time, was widely rumored to have had many prominent lovers - so long as they brought style, wit and class to the friendship."

Jack Baragwanath had a long-term relationship with a chorus girl, Ellen June Hovick. She confessed to him that when out of Broadway work she had sometimes worked as a striptease artist. Hovick swore him to secrecy and even refused to tell him the name under which she appeared. He eventually discovered it was "Gypsy Rose Lee" and eventually she became one of the biggest stars of Minsky's Burlesque. Later she made five films in Hollywood.

In 1925 Alexander Woollcott purchased most of Neshobe Island in Lake Bososeen. Other shareholders included Baragwanath, Alice Duer Miller, Beatrice Kaufman, Marc Connelly, Raoul Fleischmann, Howard Dietz and Janet Flanner. Most weekends he invited friends to the island to play games. Vincent Sheean was a regular visitor to the island. He claimed that Dorothy Parker did not enjoy her time there: "She couldn't stand Alec and his goddamned games. We both drank, which Alec couldn't stand. We sat in a corner and drank whisky... Alec was simply furious. We were in disgrace. We were anathema. We were not paying any attention to his witticisms and his goddamned games."

Joseph Hennessey, who ran the island for the visitors, later commented: "He ran the island like a benevolent monarchy, and he summoned both club members and other friends to appear at all seasons of the year; he turned the island into a crowded vacation ground where reservations must be made weeks in advance; the routine of life was completely remade to suit his wishes." Regular visitors included Dorothy Thompson, Rebecca West, Charles MacArthur, David Ogilvy, Harpo Marx, Lynn Fontanne, Alfred Lunt, Noël Coward, Laurence Olivier, Vivien Leigh and Ruth Gordon.

Jack and Neysa loved giving parties. Dorothy Parker was a regular visitor to their apartment in New York City and to their home in Sands Point on the North Shore of Long Island. One visitor Dorothy Parker later claimed that McMein made wine in the bathroom and was always entertaining friends such as Herbert Bayard Swope, Alice Duer Miller, Alexander Woollcott, Ruth Hale, Jane Grant, Charles MacArthur, Marc Connelly, George S. Kaufman, Beatrice Kaufman , Donald Ogden Stewart, George Gershwin, Ethel Barrymore and F. Scott Fitzgerald. She added that her friends loved "playing Consequences, Shedding Light, Categories, or a kind of charades that was later called The Game." George Abbott claimed that Nesya was "the greatest party giver who ever lived". He also added that they played a game called Corks, a simplified version of strip poker.

Baragwanath later recalled that he never liked Alexander Woollcott: "Among all of Neysa's friends there was only one man I disliked: Alexander Woollcott. Unfortunately, he was one of Neysa's closest and oldest attachments and seemed to regard her as his personal property. I knew, too, that she was deeply fond of him, which made my problem much harder, for I imagined the consequences of the sort of open row which Alec often seemed bent on promoting. When he and I were alone he was disarmingly pleasant, but in a group he would sometimes go out of his way to make me feel small. I was no match for him at the kind of thrust and parry that was his forte, but after a while I found that if I could make him mad, he would drop his rapier and furiously attack with a heavy mace of anger, with which he would sometimes clumsily knock himself over the head. Then I would have him.... Close as Neysa and Alec were, and as much as he loved her, his uncontrollable tongue would get the better of him and he would say something so cruel and spiteful to her that she would refuse to see him for as long as six months at a time. And there were little incidents, not infrequent ones, when he would obviously try to hurt her."

Neysa allowed Jack to hold something he called "Freedom Week" at Sands Point. This was a week every summer where Neysa agreed to be absent. The men entertained a group of women each night. These groups were loosely organized and recruited by theme: there was Models' Night, Actresses' Night, Salesladies' Night, Chorus Girls' Night and Neurotic Women's Night. One of the most popular visitors was Maria McFeeters, who later obtained Hollywood fame as Maria Montez.

In 1940 Jack Baragwanath went to Cuba where he became general manager for a nickel-mining operation encouraged by a United States government anxious to find replacement sources for the valuable metal. His efforts resulted in Cuba becoming the world's second largest nickel producer. While in the country he became close friends with Ernest Hemingway.

Neysa McMein died of cancer in New York City on 12th May, 1949. Jack Baragwanath commented in his autobiography, A Good Time was Had (1962): "There could be no doubt that our marriage had been decidedly successful." He also admitted that it was a very unconventional relationship as it "was as much a deep friendship as a marriage".

Jack Baragwanath published his autobiography, A Good Time was Had, in 1962.

© John Simkin, May 2013

Primary Sources

(1) Jack Baragwanath, A Good Time was Had ( 1962)

During my last term, I took a course in archaeology under Professor Marshall Saville. I was fascinated by his lectures on the pre-Colombian peoples of Mexico, Central America, and the West Coast of South America. Near the close of the course, Saville asked me whether I would like to join an expedition to Ecuador sponsored by a gentleman named George Heye. He was leaving in about a month, he said, with a small party to study the pre-Incan civilization of that then remote country. He needed a geologist. Would I go for six months at a salary of twenty-five dollars a month and expenses.

(2) Jack Baragwanath, A Good Time was Had ( 1962)

My first job was night-shift boss in the cyanide plant, a place full of vats, pipes, and zinc-boxes where the ground-up ore, after leaving the stamp mill, was leached in a highly poisonous solution of sodium cyanide, and the gold that was thus dissolved was deposited as a black slime on zinc shavings. The plant was a silent, eerie area, an Avernus where nothing moved but bats and big moths. My only duty was to turn certain valves at widely spaced intervals. The rest of the twelve-hour stretch I spent fighting to stay awake. In desperation I began to collect the moths that flocked, in large numbers and great variety and beauty, around two bright lights. If I had stayed there long enough, I would have become either an accomplished lepidopterist or a manic-depressive. But before long they must have recognized my technical genius for they transferred me to the Engineering Department. Around a mine there is always a faceless, nameless thing called THEY, whose Godlike decisions govern the activities of the individual and control his personal life....

As soon as I had got my coveted job underground, J. Ward Williams had begun to ride me. A lousy, lily-fingered college boy - he'd show me. And he did. With whip and spur interlarded - if one can interlard a spur-with obscene curses, he taught me the technique of mining wide and narrow quartz veins, driving drifts and cross-cuts, running raises, and sinking shafts. He made me learn to timber, lay track and hang pipe, to point blast-holes and how to space them. I was made dynamiter for one awful period during which, with one assistant, I had to load and shoot all the drill-holes in every stope at the end of each shift. Night after night I would stagger home with a"powder-headache" so severe that no aspirin, Anacin, or Bufferin could have given me any relief even had such compounds been available. I am one of those unfortunates who are allergic to nitroglycerin.

(3) Jack Baragwanath, A Good Time was Had ( 1962)

The party turned out to be great fun. There was dancing and a good deal of singing around the piano which was played by a girl-an artist, I was told-whose name was Neysa McMein. She was so striking that I could hardly take my eyes off her. Fairly tall, with a fine figure, she had a face whose high cheek-bones, greenish eyes, and heavy, dark lashes and eyebrows would have commanded attention and admiration anywhere. She had a tumbling mass of untidy, blond, I-can't-do-anything-with-it hair, and her dress was simply a dress. She wasn't a beauty, she was just beautiful. She asked me to drop in at her studio the following Saturday afternoon.

What now impresses me with that party of Irene Castle's was the number of young people there, roughly my age, who were to achieve great reputations in the arts - Bob Benchley, Marc Connelly, Sally Farnham, George Kaufman, Charlie MacArthur, Dorothy Parker, Bob Sherwood, Alec Woollcott, and several others. This group was an amazingly small nebula considering how many bright stars were to burst from it.

(4) Jack Baragwanath, A Good Time was Had ( 1962)

I went to Neysa's studio that Saturday afternoon and was welcomed pleasantly but, I thought, rather blankly. Obviously, she had forgotten where she had met me but sensed that in some misguided moment she must have invited me. She grinned and casually waved an introduction to her other guests, none of whom even looked up, then she went back to her easel where she was putting the final touches to a pretty-girl cover job in pastels. She concentrated without any regard to the noise in the room, which was roughly that of a busy steel plant. There were two pianos, back-to-back, manned by two vigorous young men, one of whom turned out to be Arthur Samuels, a young advertising man, and the other Jascha Heifetz. Over in the corner, at a rickety table, four men, including Heywood Broun and George Kaufman, were playing poker, quite oblivious to the enveloping racket. On and around a sway-backed sofa were several aspiring actresses screaming at each other above the clamor in a frantic effort to convey their egocentric thoughts. Other and even more voluble guests arrived to add to the decibels of uproar.

Neysa just stood at the easel through all this, her hair in disorder, her face and faded blue smock streaked and smudged with pastels, easily translating the tranquil beauty of her model into colored chalk on a sandboard. I sat there quietly and unnoticed, thinking what a damn fool I had been to trade the pleasure of Grace's company for this circus, but I treated myself to an occasional smile at Grace's conception of the dangers of Neysa's jungle studio.

(5) Jack Baragwanath, A Good Time was Had ( 1962)

Among all of Neysa's friends there was only one man I disliked: Alexander Woollcott. Unfortunately, he was one of Neysa's closest and oldest attachments and seemed to regard her as his personal property. I knew, too, that she was deeply fond of him, which made my problem much harder, for I imagined the consequences of the sort of open row which Alec often seemed bent on promoting. When he and I were alone he was disarmingly pleasant, but in a group he would sometimes go out of his way to make me feel small. I was no match for him at the kind of thrust and parry that was his forte, but after a while I found that if I could make him mad, he would drop his rapier and furiously attack with a heavy mace of anger, with which he would sometimes clumsily knock himself over the head. Then I would have him.

Once, after one of these melees I said to Neysa when we were alone, "You know, one of these days I may have to really go to town on our friend Alec and give him a good kick in the pants." She just looked at me quietly and said, "Perhaps some day you had better do just that."Close as Neysa and Alec were, and as much as he loved her, his uncontrollable tongue would get the better of him and he would say something so cruel and spiteful to her that she would refuse to see him for as long as six months at a time. And there were little incidents, not infrequent ones, when he would obviously try to hurt her.

(6) Brian Gallagher, Anything Goes: The Jazz Age of Neysa McMein and her Extravagant Circle of Friends (1987)

North Shore social life, even for persons as accustomed to associating with the famous and rich as Neysa and Jack were, could be rather fantastic - probably never more so, on a regular basis, than at Herbert Swope's mansion. If Neysa was more famous than rich, and people like the Whitneys were more rich than famous, Herbert Bayard Swope was both in equal, and very full, measure. His enormous, lavish parties, with their variegated lists of guests, were a great magnification of the lively entertaining Neysa and Jack did at Sands Point: everyone eventually came to Swope's, and usually had a very good time there. At one of these gatherings, Neysa was standing in a group when one member, seeing their tall, red-haired host stride majestically through his "Swope-filled room," remarked in admiration, "He has the face of some old emperor." To which FPA could not resist adding, "And I have the face of an old Greek coin," an over-assessment which Neysa immediately, and quite accurately, amended to "You have the face of an old Greek waiter."

Neysa, for the most part, shared in the general sentiment that Swope, in some mysterious way, embodied a sort of ancient nobility, even as he played his part as master of the modern revels. But she also found one of Swope's habits - his chronic, cavalier tardiness - infuriating. With his unbounded energy and nearly unbounded egotism, the powerful and influential Swope simply held to his own expansive daily schedule and could be quite oblivious to the hours his more regular friends kept. He once called George Kaufman at ten o'clock in the evening to ask what the playwright was doing about dinner and received the reply he probably deserved, namely, "digesting it." When Swope and his wife showed up a full two hours late for a dinner at Sands Point and the meal was ruined, their hostess made the best of the following few hours, but quite firmly told the Swopes as they were leaving that she would never invite them to dinner again. Apparently, she never did, although she continued to see the Swopes as part of her North Shore rounds.

Of course, in a practical social sense, Neysa could not have completely cut off someone as powerful on the North Shore scene as the editor of the New York World. Besides, Herbert Bayard Swope was probably the leading figure of an inner circle of North Shore croquet devotees among whom Neysa counted herself. Swope's estate, in fact, boasted one of the finest, and probably the most often used, croquet grounds in the area. To the extent that this prime area of the North Shore was its own little nation in summer, croquet was the national game-and virtually everyone had either to be a player or a fan. Since Neysa greatly preferred to play in the sun rather than sit in the shade watching and drinking, it was necessary, in some measure, to stay on Swope's good side, for he dominated the arrangement and progress of the matches as surely, and by the same means, as he dominated many another thing: through the sheer force of his personality.

(7) Brian Gallagher, Anything Goes: The Jazz Age of Neysa McMein and her Extravagant Circle of Friends (1987)

In June 1937, Jack, on his business travels, stopped a week at the Sherwoods' home in England. (The Algonquin crowd had by then dispersed itself as far afield as Britain and Hollywood.) During the visit, Jack was introduced to an old "historical" party game: a group is divided into two teams and a referee, with the latter picking a list of ten historical events ("Hannibal Crossing the Alps," "The Beheading of Charles I," etc. ). The captain of each team gets the first event and then must, through a series of rapid sketches which provoke "yes-no" questions, induce a teammate to guess it. The correct guesser then rushes up to the referee, gets the next event, begins "drawing" it and so on, until one team gets all ten events.

What was amusing in England proved bland and dull in New York: as Jack remembered his initial American foray with the game, "no one died laughing." Then Neysa and Howard Dietz, the lyricist and publicist, hit upon a series of modifications. First, phrases need not refer only to historical events: they could be book and song titles, mottoes, slogans, proverbs, or just about anything else. Second, teams would be put in separate rooms-with an observer from the opposing team in attendance if bets had been placed-so players might carry on boisterously and frantically without disturbing their opponents or giving away their correct choices. Third, and most importantly, clues could be conveyed either by drawing or pantomime, with a combination of the two being preferable. The result of these modifications was an instant, contagious hilarity. Clifton Webb wriggled across the floor in his white pique waistcoat doing "The Tortoise and the Hare"; players yelled and screamed their guesses as their prompter frantically alternated between outsized mime and rough sketches. The non-artists, according to Jane Grant, "quickly executed something crude but effective," while "Neysa and her artists friends ... were too taken up with line" and so usually lagged behind.

When someone guessed correctly, he or she would dash from the room in search of the referee and the next phrase. Since this was no simple game - e.g., players were forbidden to use letters or numbers in their drawings - it often went on for fifty minutes or an hour or longer, always at a frenzied pace. Early on, some conservative souls tried to insist that phrases should either be drawn or mimed, but it was Neysa's free-for¬all version-she did pause long enough to write down the rules of the variation she and Howard had devised-that quickly won out. That this version was soon prompted, almost glorified, in the pages of The New Yorker, where Jack declared George Abbott the best of its players, did not hurt in imparting a sense of madcap glamour and a distinct aura of being "in" to "The Game."

"The Game, in Jack's words, "spread like a disease. The whole country was soon playing it" - a rank overestimation only if one insists on including in the tally those millions of citizens who did not inhabit one or another of the interlocking circles in which Jack and Neysa moved. In any case, Algonquin stalwarts immediately transplanted "The Game" to Hollywood, where many of them were then working. In Hollywood, like that earlier Algonquin export, croquet, it quickly became and remained the rage. Robert Montgomery, Fredric March (once a model for Neysa), and Charlie Chaplin, not surprisingly accounted the best "actor-outer," were among its first partisans and enthusiasts. Marc Connelly was such a devotee that he would rehearse his team all afternoon in his rooms at the Garden of Allah. Nor did "The Game" prove a passing Hollywood fancy: its hold on the movie community persisted over two decades, long enough to make enthusiastic players of the likes of Gene Kelly, Grace Kelly, and, rather unexpectedly, Marlon Brando.

Some indication of how thoroughly Neysa came to be identified with "The Game" is the assertion of her good friend Jane Grant that Neysa "invented from scratch The Game"-a claim Grant might not have made had she relied strictly on her memory and not just on her impressions. A decade after Neysa's death, Cleveland Amory proclaimed "The Game" to be "the most durable American contribution to the history of parlor games." As with her drawing, so too with her games: Neysa McMein had an acute sense of what would be popular, a sense derived from her willingness to expend her mental energies on things some thought inconsequential, but which her friends found relaxing, engaging, even compelling.