Charles Macarthur

Charles Gordon MacArthur, the second youngest of seven children born to William Telfer MacArthur and Georgiana Welsted MacArthur, was born in Scranton, Pennsylvania, on 5th November, 1895. As a child he took a keen interest in reading and had ambitions to become a writer.

MacArthur moved to Chicago and found work as a journalist for the Chicago Tribune and Chicago Daily News. He also wrote short-stories and two of them, Hang It All (1921) and Rope (1923) were published by H. L. Mencken in his Smart Set magazine.

Brian Gallagher, the author of Anything Goes: The Jazz Age of Neysa McMein and her Extravagant Circle of Friends (1987), has pointed out that "Charlie MacArthur, whose smiling, curly-haired good looks and easy, bantering way with women made him a most attractive figure - and one admired, without envy, by men. Any number of women, including a thoroughly (almost suicidally) infatuated Dorothy Parker, were mad for Charlie."

MacArthur moved to New York City where he associated with members of the Algonquin Round Table. This included Robert E. Sherwood, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Alexander Woollcott, Heywood Broun, Harold Ross, Donald Ogden Stewart, Edna Ferber, Ruth Hale, Franklin Pierce Adams, Jane Grant, Neysa McMein, Marc Connelly, George S. Kaufman, Alice Duer Miller, Frank Crowninshield, Beatrice Kaufman , Samuel Behrman, John Peter Toohey, Lynn Fontanne, Alfred Lunt and Ina Claire.

Dorothy Parker fell in love with MacArthur in 1922. Her friend, Donald Ogden Stewart, remembers: "Charley was something else... Charley was marvellous. He was something all his own, and she was so in love it was really a serious, desperate thing. When Dottie fell in love, my God, it was really the works. She was madly in love. She was not a slave to love, exactly; it wasn't a game, exactly; it was really for keeps. She fell in love so deeply: she was wide open to Charley."

John Keats, the author of You Might as Well Live: The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1971) pointed out: "Charles MacArthur was a tall, handsome, talented, and altogether charming member of the Algonquin group. In 1922, he was a young newspaperman who dreamed of becoming a playwright and Dorothy Parker adored him... MacArthur, at that time, was a womanizer, which is a bit different from being simply an extremely eligible bachelor." The relationship eventually came to an end and Dorothy went through a period of depression. Stewart recalled: "I was sorry for her about Charley because she did love him terribly... She was suffering. She was having a hell of a time."

Ely Jacques Kahn, the author of The World of Swope (1965) has pointed out that MacArthur played croquet with Herbert Bayard Swope and his friends, Alice Duer Miller, Alexander Woollcott, Beatrice Kaufman, Neysa McMein, Averell Harriman, Harpo Marx and Howard Dietz, on his garden lawn: "The croquet he played was a far cry from the juvenile garden variety, or back-lawn variety. In Swope's view, his kind of croquet combined, as he once put it, the thrills of tennis, the problems of golf, and the finesse of bridge. He added that the game attracted him because it was both vicious and benign." According to Kahn it was McMein who first suggested: "Let's play without any bounds at all." This enabled Swope to say: "It makes you want to cheat and kill... The game gives release to all the evil in you." Woollcott believed that McMein was the best player but Miller "brings to the game a certain low cunning."

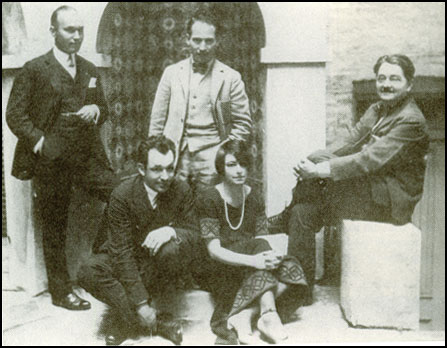

Harpo Marx and Alexander Woollcott (1924)

In 1926 MacArthur joined forces with Edward Sheldon, to write the play, Lulu Belle. The play was very controversial as it featured a prostitute played by Lenore Ulric, who bewitched powerful men in New Orleans. The theatre critic, Robert Rusie, has pointed out: "A new era, a new arena and a new appreciation for black talent were established. Cracks were appearing in a barrier once thought impervious, and the first small drops of a new social order were seeping through. It must be remembered that the barrier wasn't broken, only cracked. In 1926, the title role of Lulu Belle, a play about a black prostitute, was played by Lenore Ulric in blackface. To paraphrase Ethan Morrden, theater opens the mind, which is true, but it also reflects the society that produces and supports it. Hastened by the changes brought on by World War I, the Victorian social order was losing control, and changes were afoot. It would be another fifty years before America realized the harvest of these few small seeds."

MacArthur's next play was written with Ben Hecht, who he had worked with on the Chicago Daily News. The play was produced by Jed Harris. However, he insisted that the play needed editing and gave the job to George S. Kaufman. As Howard Teichmann, the author of George S. Kaufman: An Intimate Portrait (1972), has pointed out: "The best cutter and the fastest rewriter in the theatre was George Kaufman. He took care of the gangsters. Futhermore, Hecht and MacArthur were newspapermen and so was Kaufman; the three of them spoke a common language. He finally joked and cajoled them into writing a better, tighter, funnier script." Kaufman was also recruited as director of the play.

The play, The Front Page, was a comedy about tabloid newspaper reporters covering the execution of Earl Williams, a white man and a suspected member of the American Communist Party who had been convicted of killing a black policeman. Williams is based on the case of Tommy O'Connor, who escaped from a Chicago courthouse in 1923. It opened at the Times Square Theatre on 14th August, 1928. The play was a smash hit, running 278 performances before closing in April 1929.

MacArthur and Hecht developed a reputation for hard-drinking. Howard Teichmann argues that this caused problems with the director of the play: "Stories of the wonderful wildness of Hecht and MacArthur persist in theatrical circles to this day. Kaufman, with his built-in sense of discipline, almost left the show. When he found them in a speakeasy, they would offer him a drink. Kaufman who took whiskey as though it were medicine managed to go through a lifetime of cocktail parties by quietly pouring his drinks into convenient receptacles."

MacArthur met the actress, Helen Hayes, at the home of Neysa McMein. According to Brian Gallagher: "It was at Neysa's studio that Charlie found the woman he was to love. It seemed, at the time, a highly unlikely and distinctly unsuitable choice for the high-spirited, urbane newspaperman and playwright. By 1925, when she met Charlie, Helen Hayes was long on stage experience but short on life experience. As natural, charming, and smart as she was on stage, she was awkward and tongue-tied off stage, most particularly when confronted with the challenging wit and social niceties of the Algonquin circle. When she managed to say something, it was often the wrong thing - in a group that put a premium on saying the right thing (by its own strict, if idiosyncratic, standards). Charlie, who blithely ignored the inconvenience of already having a wife off some where, was surprisingly taken with the petite, beautiful Helen. 'He saw the woman lurking in the girl,' as she later put it, and he was determined, in his own fun-loving way, to bring the woman out."

MacArthur now moved to Hollywood and wrote the screenplays for The Girl Said No (1930), Billy the Kid (1930), Way for a Sailor (1930), The Front Page (1930), New Adventures of Get Rich Quick Wallingford (1931), Hell Divers (1931), The Unholy Garden (1931), Rasputin the Mad Monk (1932), Crime Without Passion (1934), Once in a Blue Moon (1935), Barbary Coast (1935), The Scoundrel (1935), Soak the Rich (1936), Gunga Din (1939), Wuthering Heights (1939) and His Girl Friday (1940).

MacArthur married Helen Hayes and established a home in Nyack. Their adopted son, James MacArthur, became a successful actor. In 1949 their nineteen-year old daughter Mary MacArthur died of polio. His writing partner, Ben Hecht, later commented: "Charlie was more than a man of talent. He was himself a great piece of writing. His gaiety, wildness and kindness, his love for his bride Helen, and his two children, and for his clan of brothers and sisters - his wit and his adventures will live a long, long while".

Charles Gordon MacArthur died on 21st April, 1956.

Primary Sources

(1) John Keats, You Might as Well Live: The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1971)

Charles MacArthur was a tall, handsome, talented, and altogether charming member of the Algonquin group. In 1922, he was a young newspaperman who dreamed of becoming a playwright and Dorothy Parker adored him... MacArthur, at that time, was a womanizer, which is a bit different from being simply an extremely eligible bachelor.

(2) Howard Teichmann, George S. Kaufman: An Intimate Portrait (1972)

Sometime during the rehearsals and the try-outs of The Royal Family, Jed Harris took an option on a play written by two Chicago newspapermen about two Chicago newspapermen. Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur had come up with The Front Page. It was good, but in the unchallenged opinion of Harris it needed cutting and rewriting. Of equal importance was the fact that no matter how many times the play was rewritten, gangsters invariably turned up in the third act.

The best cutter and the fastest rewriter in the theatre was George Kaufman. He took care of the gangsters. Futhermore, Hecht and MacArthur were newspapermen and so was Kaufman; the three of them spoke a common language. He finally joked and cajoled them into writing a better, tighter, funnier script.

Harris then convinced him, as only Harris could, to take on the directorial assignment. According to Harris' general manager at that time, Herman Shumlin, who later became one of the theatre's most accomplished producer-directors, Kaufman had already done a few jobs of directing, but never with his name on the program. The Front Page was his first time out officially.

Stories of the wonderful wildness of Hecht and MacArthur persist in theatrical circles to this day. Kaufman, with his built-in sense of discipline, almost left the show. When he found them in a speakeasy, they would offer him a drink. Kaufman who took whiskey as though it were medicine managed to go

through a lifetime of cocktail parties by quietly pouring his drinks into convenient receptacles. "I happen to know," he once told Ben Hecht, "that rubber plant over there has been drunk four times this week on my drinks alone."Casting a play is one of the director's most important tasks. Kaufman the newspaperman made it his business to see almost every play that opened on Broadway. Kaufman the playwright was keenly knowledgeable as to the exact talent of almost every available actor. Kaufman the director, therefore, cast The Front Page almost perfectly. Osgood Perkins and Lee Tracy headed the players. They were supported by actors whose names or faces became nationally and internationally known or recognized via stage and film for thirty years: Allen Jenkins, William Foran, Tammany Young, Joseph Spurin-Calleia, Walter Baldwin, Eduardo Cianelli, Frances Fuller, George Barbier.

As the play went into rehearsal, it soon became apparent that Kaufman's casting was found lacking in a single role. George S. Kaufman had been unable to pick a good prostitute. At the end of five days, the actress, whoever she was, was fired. For a replacement he got Dorothy Stickney. Miss Stickney, who had been married just under a year to Kaufman's friend and first director, Howard Lindsay, created the role of Molly Malloy, the Clark Street tart. Her entrance line on bursting into a roomful of drinking, smoking, and classically cursing reporters was, "I've been looking for you bastards!"

Born in Dickinson, North Dakota, educated at St. Catherine's College, and married to a man who at one time had seriously considered becoming an ordained minister, Miss Stickney at first found that line definitely objectionable. After some hassling, Kaufman took the basically timid, gentle, very ladylike lady aside and explained that "I've been looking for you bastards!" was a line inserted solely for the purpose of arousing sympathy from the audience for the character she was playing. After that, he had no trouble with her.

(3) Brian Gallagher, Anything Goes: The Jazz Age of Neysa McMein and her Extravagant Circle of Friends (1987)

One of the men ranked highest must have been Charlie MacArthur, whose smiling, curly-haired good looks and easy, bantering way with women made him a most attractive figure - and one admired, without envy, by men. Any number of women, including a thoroughly (almost suicidally) infatuated Dorothy Parker, were mad for Charlie; but it was at Neysa's studio that Charlie found the woman he was to love. It seemed, at the time, a highly unlikely and distinctly unsuitable choice for the high-spirited, urbane newspaperman and playwright.

By 1925, when she met Charlie, Helen Hayes was long on stage experience but short on life experience. As natural, charming, and smart as she was on stage, she was awkward and tongue-tied off stage, most particularly when confronted with the challenging wit and social niceties of the Algonquin circle. When she managed to say something, it was often the wrong thing-in a group that put a premium on saying the right thing (by its own strict, if idiosyncratic, standards). Charlie, who blithely ignored the inconvenience of already having a wife off some where, was surprisingly taken with the petite, beautiful Helen. "He saw the woman lurking in the girl," as she later put it, and he was determined, in his own fun-loving way, to bring the woman out.