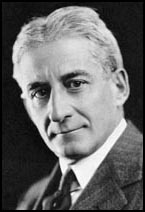

Herbert Bayard Swope

Herbert Bayard Swope, the son of German immigrants Ida Cohn and Isaac Swope, was born in St. Louis, Missouri on 5th January, 1882. Swope became a reporter with the New York World. During the First World War a series of articles entitled "Inside the German Empire" won him the Pulitizer Prize for reporting. A book of these articles, German Empire: In the Third Year of the War, was published in 1917.

Richard O'Connor has argued that not since Richard Harding Davis had any newspaperman possessed the quality of Swope: "Not since the salad days of Richard Harding Davis had any newspaperman possessed the persuasive quality of Herbert Bayard Swope. Red-haired, with a prowlike jaw and a jaunty, well-tailored figure, a man of cyclonic energies, he had battled his way up through the reportorial ranks to the city desk, had imposed a field marshal's presence on World War I as something more than a correspondent and less than a plenipotentiary, and had published the first account of the Versailles Treaty and the League of Nations covenant." Swope was willing to tackle controversial subjects. He once said that: "I can't give you a sure-fire formula for success, but I can give you a formula for failure: try to please everybody all the time." He told his friend, Heywood Broun: "What I try to do in my paper is to give the public part of what it wants and part of what it ought to have whether it wants it or not."

After the war Swope was appointed editor of the newspaper, New York World. Swope later recalled: "The secret of a successful newspaper is to take one story each day and bang the hell out of it. Give the public what it wants to have and part of what it ought to have whether it wants it or not." He added: "I cannot give you the formula for success, but I can give you the formula for failure - which is: Try to please everybody."

Swope recruited a significant number of columnists, most of them on a three-times-a-week basis. This included Alexander Woollcott, Heywood Broun, William Bolitho, Franklin Pierce Adams, Clare Sheridan, Deems Taylor, Samuel Chotzinoff, Laurence Stallings, Harry Hansen and St. John Greer Ervine. Swope's biographer, Ely Jacques Kahn, has argued: "Its contributors were encouraged by Swope, who never wrote a line for it himself, to say whatever they liked, restricted only by the laws of libel and the dictates of taste. To keep their stuff from sounding stale, moreover, he refused to build up a bank of ready-to-print columns; everybody wrote his copy for the following day's paper."

In 1920 the young journalist, Briton Hadden, wanted to work under Swope. Hadden marched into Swope's office unannounced. Swope yelled: "Who are you." He replied: "My name is Briton Hadden, and I want a job." When the editor told him to get out, he commented: "Mr. Swope, you're interfering with my destiny." Intrigued, Swope asked Hadden what his destiny entailed. He then gave him a detailed account of his plans to publish a news magazine but first he felt he had to learn his craft under Swope. Impressed by his answer, Swope gave him a job on his newspaper. Hadden's reports soon became appearing on the front page. Swope liked Hadden's conservational style of writing and began giving him the top stories to cover. One of his fellow reporters suggested that Hadden had an "intelligent brain, with baby thoughts". Swope also invited him to his house for dinner and became attending his legendry parties, where he met the writer, F. Scott Fitzgerald, who later used these experiences for his masterpiece, The Great Gatsby (1925).

Stanley Walker, the city editor of the New York Herald Tribune, wrote: "He (Swope) is as easy to ignore as a cyclone. His gift of gab is a torrential and terrifying thing. He is probably the most charming extrovert in the western world. His brain is crammed with a million oddments of information, and only a dolt would make a bet with him on an issue concerning facts... In the days when he was a dynamic practicing journalist in New York, many other newspapermen were distinguished by their gall and brass, but the man who stood out among his fellows... was Herbert Bayard Swope." Swope told his journalists: "Don't forget that the only two things people read in a story are the first and last sentences. Give them blood in the eye on the first one."

Clare Sheridan found Swope a stimulating companion. She told her friend, Maxine Elliott. "I asked him, when I was able to get a word in edgeways, how he managed to revitalize, he seemed to me to expend so much energy. He said he got it back from me, from everyone, that what he gives out he gets back; it is a sort of circle. He was so vibrant that I found my heart thumping with excitement, as though I had drunk champagne, which I hadn't! He talks a lot, but talks well; is never dull."

The actress, Helen Hayes, agreed: "Never have I heard a man talk so much and say-so much." The writer Abe Burrows, added: "He never wobbled. If he told you a fact or a piece of political information, he said it as though it were about to be carved in granite. I can't think of anyone who would question or doubt anything Swope had to say while he was saving it, or for at least an hour after he had said it. After a while you might disagree with what he had said or find some other flaw in his logic. But while he was talking to you his impact was overwhelming."

In October 1921 Swope started a 21-day crusade against the Ku Klux Klan in October 1921 which won the newspaper the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service in 1922. It has been claimed that this was one of the most important examples of investigative journalism in American history. The KKK activities continued and in 1924, Swope's star columnist, Heywood Broun, took up the attack and denounced the KKK as a cowardly and un-American organization. On 4th July, Broun found a burning cross outside his home in Connecticut, but he refused to stop writing about this issue. Broun wrote: "We must bring ourselves to realize that it is necessary to support free speech for the things we hate in order to ensure it for the things in which we believe with all our heart."

In 1927 Ralph Pulitzer came into conflict with Heywood Broun, one of his main columnists. For several years Broun had campaigned for the release of Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco after they were convicted for murdering Frederick Parmenter and Alessandro Berardelli during a robbery. In 1927 Governor Alvan T. Fuller appointed a three-member panel of Harvard President Abbott Lawrence Lowell, the President of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Samuel W. Stratton, and the novelist, Robert Grant to conduct a complete review of the case and determine if the trials were fair. The committee reported that no new trial was called for and based on that assessment Governor Fuller refused to delay their executions or grant clemency. It now became clear that Sacco and Vanzetti would be executed.

Broun was furious and on 5th August he wrote in New York World: "Alvan T. Fuller never had any intention in all his investigation but to put a new and higher polish upon the proceedings. The justice of the business was not his concern. He hoped to make it respectable. He called old men from high places to stand behind his chair so that he might seem to speak with all the authority of a high priest or a Pilate. What more can these immigrants from Italy expect? It is not every prisoner who has a President of Harvard University throw on the switch for him. And Robert Grant is not only a former Judge but one of the most popular dinner guests in Boston. If this is a lynching, at least the fish peddler and his friend the factory hand may take unction to their souls that they will die at the hands of men in dinner coats or academic gowns, according to the conventionalities required by the hour of execution."

The following day Broun returned to the attack. He argued that Governor Alvan T. Fuller had vindicated Judge Webster Thayer "of prejudice wholly upon the testimony of the record". Broun had pointed out that Fuller had "overlooked entirely the large amount of testimony from reliable witnesses that the Judge spoke bitterly of the prisoners while the trial was on." Broun added: "It is just as important to consider Thayer's mood during the proceedings as to look over the words which he uttered. Since the denial of the last appeal, Thayer has been most reticent, and has declared that it is his practice never to make public statements concerning any judicial matters which come before him. Possibly he never did make public statements, but certainly there is a mass of testimony from unimpeachable persons that he was not so careful in locker rooms and trains and club lounges."

However, it was his comments on Abbott Lawrence Lowell that caused the most controversy: "From now on, I want to know, will the institution of learning in Cambridge which once we called Harvard be known as Hangman's House?" The New York Times complained in an editorial that Broun's "educated sneer at the President of Harvard for having undertaken a great civic duty shows better than an explosion the wild and irresponsible spirit which is abroad".

Herbert Bayard Swope was on holiday and Ralph Pulitzer decided to stop Heywood Broun writing about the case after a board meeting on 11th August. As Richard O'Connor, the author of Heywood Broun: A Biography (1975) has pointed out: "The editorial board's decision certainly was defensible if one takes into account the climate of the twenties... The country was acutely aware of what some newspapers termed the Red Menace, now that all hope that the Bolshevik dictatorship in Moscow might crumble or be overthrown had vanished."

On 12th August 1927 Pulitzer published a statement in the newspaper: "The New York World has always believed in allowing the fullest possible expression of individual opinion to those of its special writers who write under their own names. Straining its interpretation of this privilege, the New York World allowed Mr. Heywood Brown to write two articles on the Sacco-Vanzetti case, in which he expressed his personal opinion with the utmost extravagance. The New York World then instructed him, now that he had made his own position clear, to select other subjects for his next articles. Mr. Broun, however, continued to write on the Sacco-Vanzetti case. The New York World, thereupon, exercising its right of final decision as to what it will publish in its columns, has omitted all articles submitted by Mr. Broun."

Heywood Broun was not willing to be censored and asked for his contract to be terminated. Pulitzer refused and reminded him that his contract contained a passage that meant he could not work for any other newspaper for the next three years. Broun now went on strike. On the 27th August, 1927, Pulitzer wrote: "Mr. Broun's temperately reasoned argument does not alter the basic fact that it is the function of a writer to write and the function of an editor to edit. Ninety-nine times out of a hundred I publish Mr. Broun's articles with pleasure and read them with delight; but the hundredth time is altogether different. Then something arises like the Sacco-Vanzetti case. Here Mr. Broun's unmeasured invective against Gov. Fuller and his committee seemed to the New York World to be inflammatory, and to encourage those revolutionists who care nothing for the fate of Sacco and Vanzetti, nor for the vindication of justice, but are using this case as a vehicle of their propaganda. The New York World, for these reasons, judged Mr. Broun's writings on the case to be disastrous to the attempt, in which the New York World was engaged, of trying to save the two condemned men from the electric chair. The New York World could not conscientiously accept the responsibility for continuing to publish such articles... The New York World still considers Mr. Broun a brilliant member of its staff, albeit taking a witch's Sabbatical. It will regard it as a pleasure to print future contributions from him. But it will never abdicate its right to edit them."

Broun was not allowed to write for a newspaper Oswald Garrison Villard to write a weekly page of comment and opinion for The Nation. While he was away the circulation of the New York World dropped dramatically. Samuel Hopkins Adams blamed the crisis on the inexperienced Ralph Pulitzer: "Joseph Pulitzer had made a disastrous will, taking control of the paper from two sons (Joseph II and Herbert) who were able and devoted journalists, and vested it in the cadet of the family, an amiable playboy."

Herbert Bayard Swope managed to persuade Broun to return and his first column was on 2nd January 1928. The dispute changed the image of the New York World. As Ely Jacques Kahn, the author of The World of Swope (1965) pointed out: "the shining integrity of the op ed page seemed to have been irreparably, if not fatally, tarnished" by the temporary silencing of Broun and the suspicion would linger that the columnists weren't absolutely free to speak their minds.

Heywood Broun was a strong supporter of birth-control. These views were not shared by Ralph Pulitzer who was frightened by the power of the Roman Catholic Church in New York City. Fearing that he would be censored, Broun wrote an article about the subject in The Nation. He argued: "In the mind of the New York World there is something dirty about birth control. In a quiet way the paper may even approve of the movement, but it is not the sort of thing one likes to talk about in print... There is not a single New York editor who does not live in mortal terror of the power of this group (Roman Catholic Church). It is not a case of numbers but of organization."

Pulitzer was furious with Broun for exposing the censorship concerning the discussion of birth-control and on 3rd May, 1928, Broun's column was missing from the New York World. Instead it included the following statement: "The New York World has decided to dispense with the services of Heywood Broun. His disloyalty to this newspaper makes any further association impossible."

Swope bought a home in Sands Point on the North Shore of Long Island. He loved entertaining friends such as Neysa McMein, Jack Baragwanath, Alice Duer Miller, Alexander Woollcott, Ruth Hale, Jane Grant, Charles MacArthur, Marc Connelly, George S. Kaufman, Beatrice Kaufman , Donald Ogden Stewart, Averell Harriman, Harpo Marx, Howard Dietz, George Abbott, George Gershwin, Ethel Barrymore and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Abbott claimed that Nesya was "the greatest party giver who ever lived". He also added that they played a game called Corks, a simplified version of strip poker.

Ely Jacques Kahn, the author of The World of Swope (1965) has pointed out that Herbert Bayard Swope played croquet with his friends, Miller, McMein, Woollcott, Kaufman, MacArthur, Harriman, Marx and Dietz, on his garden lawn: "The croquet he played was a far cry from the juvenile garden variety, or back-lawn variety. In Swope's view, his kind of croquet combined, as he once put it, the thrills of tennis, the problems of golf, and the finesse of bridge. He added that the game attracted him because it was both vicious and benign." According to Kahn it was McMein who first suggested: "Let's play without any bounds at all." This enabled Swope to say: "It makes you want to cheat and kill... The game gives release to all the evil in you." Woollcott believed that McMein was the best player but Miller "brings to the game a certain low cunning."

Brian Gallagher, the author of Anything Goes: The Jazz Age of Neysa McMein and her Extravagant Circle of Friends (1987), claims that Swope became very close to the artist, Neysa McMein, and her husband, Jack Baragwanath, who also lived in Sands Point: "North Shore social life, even for persons as accustomed to associating with the famous and rich as Neysa and Jack were, could be rather fantastic - probably never more so, on a regular basis, than at Herbert Swope's mansion. If Neysa was more famous than rich, and people like the Whitneys were more rich than famous, Herbert Bayard Swope was both in equal, and very full, measure. His enormous, lavish parties, with their variegated lists of guests, were a great magnification of the lively entertaining Neysa and Jack did at Sands Point: everyone eventually came to Swope's, and usually had a very good time there.... Neysa, for the most part, shared in the general sentiment that Swope, in some mysterious way, embodied a sort of ancient nobility, even as he played his part as master of the modern revels. But she also found one of Swope's habits - his chronic, cavalier tardiness - infuriating. With his unbounded energy and nearly unbounded egotism, the powerful and influential Swope simply held to his own expansive daily schedule and could be quite oblivious to the hours his more regular friends kept... When Swope and his wife showed up a full two hours late for a dinner at Sands Point and the meal was ruined, their hostess made the best of the following few hours, but quite firmly told the Swopes as they were leaving that she would never invite them to dinner again. Apparently, she never did, although she continued to see the Swopes as part of her North Shore rounds."

Herbert Bayard Swope died on 20th June, 1958.

Primary Sources

(1) Richard O'Connor, Heywood Broun: A Biography (1975)

Not since the salad days of Richard Harding Davis had any newspaperman possessed the persuasive quality of Herbert Bayard Swope. Red-haired, with a prowlike jaw and a jaunty, well-tailored figure, a man of cyclonic energies, he had battled his way up through the reportorial ranks to the city desk, had imposed a field marshal's presence on World War I as something more than a correspondent and less than a plenipotentiary, and had published the first account of the Versailles Treaty and the League of Nations covenant.

(2) Stanley Walker, Saturday Evening Post (4th June, 1938)

He (Swope) is as easy to ignore as a cyclone. His gift of gab is a torrential and terrifying thing. He is probably the most charming extrovert in the western world. His brain is crammed with a million oddments of information, and only a dolt would make a bet with him on an issue concerning facts... In the days when he was a dynamic practicing journalist in New York, many other newspapermen were distinguished by their gall and brass, but the man who stood out among his fellows... was Herbert Bayard Swope.

He met all the big men of that momentous time, and he met them as an equal. He played golf with Lord Northcliffe. He captivated Queen Marie of Rumania. He put his hand to limericks to please President Wilson. This, then was history, and Herbert Bayard Swope was in the middle of it, helping make it.

(3) Ely Jacques Kahn, The World of Swope (1965)

At times it (New York World) was flat and at other times excessive cute, but for a daily commodity it was consistently good. And it was fresh in both senses of the word. Its contributors were encouraged by Swope, who never wrote a line for it himself, to say whatever they liked, restricted only by the laws of libel and the dictates of taste. To keep their stuff from sounding stale, moreover, he refused to build up a bank of ready-to-print columns; everybody wrote his copy for the following day's paper.

(4) Brian Gallagher, Anything Goes: The Jazz Age of Neysa McMein and her Extravagant Circle of Friends (1987)

North Shore social life, even for persons as accustomed to associating with the famous and rich as Neysa and Jack were, could be rather fantastic - probably never more so, on a regular basis, than at Herbert Swope's mansion. If Neysa was more famous than rich, and people like the Whitneys were more rich than famous, Herbert Bayard Swope was both in equal, and very full, measure. His enormous, lavish parties, with their variegated lists of guests, were a great magnification of the lively entertaining Neysa and Jack did at Sands Point: everyone eventually came to Swope's, and usually had a very good time there. At one of these gatherings, Neysa was standing in a group when one member, seeing their tall, red-haired host stride majestically through his "Swope-filled room," remarked in admiration, "He has the face of some old emperor." To which FPA could not resist adding, "And I have the face of an old Greek coin," an over-assessment which Neysa immediately, and quite accurately, amended to "You have the face of an old Greek waiter."

Neysa, for the most part, shared in the general sentiment that Swope, in some mysterious way, embodied a sort of ancient nobility, even as he played his part as master of the modern revels. But she also found one of Swope's habits - his chronic, cavalier tardiness - infuriating. With his unbounded energy and nearly unbounded egotism, the powerful and influential Swope simply held to his own expansive daily schedule and could be quite oblivious to the hours his more regular friends kept. He once called George Kaufman at ten o'clock in the evening to ask what the playwright was doing about dinner and received the reply he probably deserved, namely, "digesting it." When Swope and his wife showed up a full two hours late for a dinner at Sands Point and the meal was ruined, their hostess made the best of the following few hours, but quite firmly told the Swopes as they were leaving that she would never invite them to dinner again. Apparently, she never did, although she continued to see the Swopes as part of her North Shore rounds.

Of course, in a practical social sense, Neysa could not have completely cut off someone as powerful on the North Shore scene as the editor of the New York World. Besides, Herbert Bayard Swope was probably the leading figure of an inner circle of North Shore croquet devotees among whom Neysa counted herself. Swope's estate, in fact, boasted one of the finest, and probably the most often used, croquet grounds in the area. To the extent that this prime area of the North Shore was its own little nation in summer, croquet was the national game-and virtually everyone had either to be a player or a fan. Since Neysa greatly preferred to play in the sun rather than sit in the shade watching and drinking, it was necessary, in some measure, to stay on Swope's good side, for he dominated the arrangement and progress of the matches as surely, and by the same means, as he dominated many another thing: through the sheer force of his personality.