Birth Control

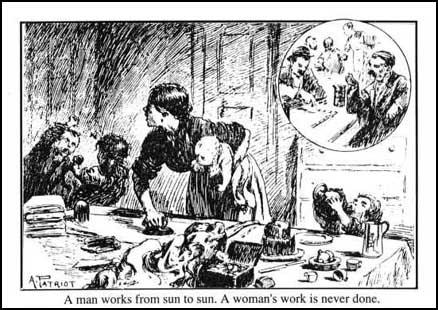

Working class women were expected to work until they had children. These women tended to have more children than upper and middle class wives. In the middle of the 19th century, the average married woman gave birth to six children. Over 35% of all married women had eight or more children.

The Church was totally opposed to the use of contraception to control family size. Several people, including Richard Carlile had been sent to prison for publishing books on the subject. In 1877 Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh decided to publish The Fruits of Philosophy, written by Charles Knowlton, a book that advocated birth control. Besant and Bradlaugh were charged with publishing material that was "likely to deprave or corrupt those whose minds are open to immoral influences". In court they argued that "we think it more moral to prevent conception of children than, after they are born, to murder them by want of food, air and clothing." Besant and Bradlaugh were both found guilty of publishing an "obscene libel" and sentenced to six months in prison. At the Court of Appeal the sentence was quashed.

Mary Gladstone married Harry Drew, the curate of Hawarden in Westminster Abbey on 2nd February 1886. In August 1886 she miscarried a son and was dangerously ill for five months. Mary now became involved in a debate with her father, William Ewart Gladstone, the prime minister, on the subject of birth-control. Mary discovered that her father had been sent a copy of The Ethics of Marriage by Hiram Sterling Pomeroy. She wrote to her father about the book on 27th October, 1887: "Dearest Father: I saw that a book called Ethics of Marriage was sent to you, & I am writing this to ask you to lend it me. You may think it an unfitting book to lend, but perhaps you do not know of the great battle we of this generation have to fight, on behalf of morality in marriage. If I did not know that this book deals with what I am referring to, I should not open the subject at all, as I think it sad & useless for any one to know of these horrors unless the, are obliged to try & counteract them. For when one once knows of an evil in our midst, one is partly responsible for it. I do not wish to speak to Mama about it, because when I did, she in her innocence, thought that by ignoring it, the evil would cease to exist."

In the letter Mary pointed out that it was becoming clear that society was changing. "What is called the American sin is now almost universally practised in the upper classes; one sign of it easily seen is the Peerage, where you will see that among those married in the last 15 years, the children of the large majority are under 5 in number, & it is spreading even among the clergy, & from them to the poorer classes. The Church of England Purity Society has been driven to take up the question, & it was openly dealt with at tile Church Congress. As a clergyman's wife, I have been a good deal consulted, & have found myself almost alone amongst my friends & contemporaries, in the line I have taken ... everything that hacks up this line strengthens this line, is of inestimable value to me, & therefore this book will be a help to me ... It is almost impossible to make people see it is a sin against nature as well as against God."

After the court-case Annie Besant wrote and published her own book advocating birth control entitled The Laws of Population. The idea of a woman advocating birth-control received wide-publicity. Newspapers like The Times accused Besant of writing "an indecent, lewd, filthy, bawdy and obscene book".

In 1918 Marie Stopes wrote a concise guide to contraception called Wise Parenthood. Marie Stopes' book upset the leaders of the Church of England who believed it was wrong to advocate the use of birth control. Roman Catholics were especially angry, as the Pope had made it clear that he condemned all forms of contraception. Despite this opposition, Marie continued her campaign and in 1921 founded the Society for Constructive Birth Control. With financial help from her rich second husband, Humphrey Roe, Marie also opened the first of her birth-control clinics in Holloway on 17th March 1921.

The 1923 Dora Russell along with John Maynard Keynes, paid for the legal costs to obtain the freedom of Guy Aldred and Rose Witcop after they had been found guilty of selling pamphlets on contraception. The following year, Dora, with the support of Katharine Glasier, Susamn Lawrence, Margaret Bonfield, Dorothy Jewson and H. G. Wells founded the Workers' Birth Control Group. Dora also campaigned within the Labour Party for birth-control clinics but this was rejected as they feared losing the Roman Catholic vote.

Primary Sources

(1) In 1832 Dr. Charles Knowlton of Ashfield, Massachusetts was sentenced to three months hard labour for writing and publishing The Fruits of Philosophy, a book the provided details of different methods of birth control. Although constantly prosecuted, over the next forty years Knowlton sold 40,000 copies of his book.

In how many instances does the hard-working father, and more especially the mother, of a poor family remain slaves throughout their lives… toiling to live, and living to toil; when, if their offspring had been limited to two or three only, they might have enjoyed comfort and comparative affluence? How often is the health of the mother, giving birth every year to an infant and compelled to toil on… how often is the mother's comfort, health, nay, even her life thus sacrificed? Many women cannot give birth to healthy, living children. Is it desirable - is it moral, that such women should become pregnant?

(2) In 1877 Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh attempted to publish The Fruits of Philosophy in Britain. The couple were immediately arrested and charged with publishing an 'obscene' book. Hardinge Gifford, the public prosecutor, explained why Besant and Bradlaugh were on trial.

I say that this is a dirty, filthy book, and the test of it is that no human being would allow that book on his table, no decently educated English husband would allow even his wife to have it…the object of it is to enable a person to have sexual intercourse, and not to have that which in the order of providence is the natural result of that sexual intercourse. That is the only purpose of the book and all the instruction in the other parts of the book leads up to that proposition.

(3) Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh were both found guilty and sentenced to six months imprisonment, and fined £200. However in February 1878, the Court of Appeal reversed the judgement and the sentence was quashed. Annie Besant responded to this decision by writing her own book on birth control. She explained in her autobiography her reasons for this.

I wrote a pamphlet entitled The Law of Population giving the arguments which had convinced me of its truth, the terrible distress and degradation entailed on families by overcrowding and the lack of necessaries of life, pleading for early marriages that prostitution might be destroyed, and limitation of the family that pauperism might be avoided, finally giving the information which rendered early marriage without these evils possible. This pamphlet was put in circulation as representing our views on the subject.

We continued the sale of Knowlton's Fruits of Philosophy for some time until we received an intimation that no further prosecution would be attempted, and on this we at once dropped its publication, substituting for it my Law of Population.

(4) Annie Besant, The Law of Population (1878)

War, infanticide, hardship, famine, disease, murder of the aged, all these are among the positive checks which keep down the increase of population among savage tribes. War carries off the young men, full of vigour, the warriors in their prime of life, the strongest, the most robust, the most fiery - those in fact, who, from their physical strength and energy would be most likely to add largely to the number of the tribe. Infanticide, most prevalent where means of existence are most restricted, is largely practised among barbarous nations, the custom being due, to a large extent, to the difficulty of providing food for a large family.

Men, women, and children, who would be doomed to death in the savage state, have their lives prolonged by civilization; the sickly, whom the hardships of the savage struggle for existence would kill off, are carefully tended in hospitals, and saved by medical skill; the parents, whose thread of life would be cut short, are cherished on into prolonged old age; the feeble, who would be left to starve, are tenderly shielded from hardship, and life's road is made the smoother for the lame; the average life is lengthened, and more and more thought is brought to bear on the causes of preventable disease; better drainage, better homes, better food, better clothing, all these, among the more comfortable classes, remove many of the natural checks to population.

In England our population is growing rapidly enough to cause anxiety… England has almost doubled her population during the last fifty years. In 1810 the population of England and Wales was about 10,000,000, and in 1860 it was about 20,000,000. "At the present time" writes Professor Henry Fawcett, "it is growing at the rate of 200,000 every year, which is almost equivalent to the population of the country of Northampton… it is possible that the population of England will be 80 millions in 1960."

(5) Annie Besant, The Law of Population (1878)

One of the earliest signs of too rapidly increasing population is the overcrowding of the poor. Just as the overcrowded seedlings spoil each other's growth, so do the overcrowded poor injure each other morally, mentally and physically. Whether we study town or country the result of our enquiries is the same - the houses are too small and the families are too large. Can there be any doubt that it is the large families so common among the English poor that is the root of this overcrowding? For not only would the "model-lodging house" have been less crowded if the parents, instead of having ten children, had only two, but with fewer children less money would be needed for food and clothing, and more could be spared for rent.

It is clearly useless to preach the limitation of the family and to conceal the means whereby such limitation may be effected. If the limitation be a duty it cannot be wrong to afford such information as shall enable people to discharge it… At present all one can do is to lay before the public the various checks suggested by doctors.

(6) Selina Cooper built up a library of books that she made available to other women in the textile factory where they worked in the 1890s. One of her books was Dr. Thomas Allison's Book for Married Women (1894).

Women have rights as well as men, and to force a woman to have more children than her constitution will bear, or is her desire to have, is an act of cruelty that no upright man would sanction. It is against the true dignity of a woman to become a mere childbearing drudge. From a health standpoint, it is better to use preventative means.

(7) Selina Cooper's daughter remembers how her mother Selina Cooper gave advice to friends and neighbours on birth control.

Birth control wasn't much talked about then, but my mother used to give a talk to the women that came here to our house about it… She used to meet with a lot of opposition, because there was quite a lot of Catholics. But she used to talk about things - and elementary hygiene and elementary science and biology, and things we never got before.

(8) Mary Gladstone Drew, letter of William Ewart Gladstone (27th October, 1886)

Dearest Father: I saw that a book called Ethics of Marriage was sent to you, & I am writing this to ask you to lend it me. You may think it an unfitting book to lend, but perhaps you do not know of the great battle we of this generation have to fight, on behalf of morality in marriage. If I did not know that this book deals with what I am referring to, I should not open the subject at all, as I think it sad & useless for any one to know of these horrors unless the, are obliged to try & counteract them.

For when one once knows of an evil in our midst, one is partly responsible for it. I do not wish to speak to Mama about it, because when I did, she in her innocence, thought that by ignoring it, the evil would cease to exist. What is called the 'American sin' is now almost universally practised in the upper classes; one sign of it easily seen is the Peerage, where you will see that among those married in the last 15 years, the children of the large majority are under 5 in number, & it is spreading even among the clergy, & from them to the poorer classes. The Church of England Purity Society has been driven to take up the question, & it was openly dealt with at tile Church Congress. As a clergyman's wife, I have been a good deal consulted, & have found myself almost alone amongst my friends & contemporaries, in the line I have taken ... everything that hacks up this line strengthens this line, is of inestimable value to me, & therefore this book will be a help to me ... It is almost impossible to make people see it is a sin against nature as well as against God. But it is possible to impress them on the physical side. Dr. Matthews Duncan, Sir Andrew Clark & Sir James Paget utterly condemn the practice, & declare the physical consequences to be extremely bad. But they have little influence. If you quote them, the answer always is "They belong to the past generation. They cannot judge of the difficulties of this one."

I would not have dreamed of opening the subject, only that as you are reading the book, you cannot help becoming aware of the present sad state of things. It is what frightens me about England's future.

(9) Margaret Sanger, An Autobiography (1938)

During these years in New York more and more my calls began to come from the Lower East Side, as though I were being magnetically drawn there by some force outside my control. I hated the wretchedness and hopelessness of the poor, and never experienced that satisfaction in working among them that so many noble women have found. My concern for my patients was now quite different from my earlier hospital attitude. I could see that much was wrong with them that did not appear in the physiological or medical diagnosis. A woman in childbirth was not merely a woman in childbirth. My expanded outlook included a view other background, her potentialities as a human being, the kind of children she was bearing, and what was going to happen to them.

As soon as the neighbors learned that a nurse was in the building they came in a friendly way to visit, often carrying fruit, jellies, or fish made after a cherished recipe. It was infinitely pathetic to me that they, so poor themselves, should bring me food. Later they drifted in again with the excuse of getting the plate, and sat down for a nice talk; there was no hurry. Always back of the little gift was the question, "I am pregnant (or my daughter, or my sister is). Tell me something to keep from having another baby. We cannot afford another yet."

I tried to explain the only two methods I had ever heard of among the middle classes, both of which were invariably brushed aside as unacceptable.. They were of no certain avail to the wife because they placed the burden of responsibility solely upon the husband - a burden which he seldom assumed. What she was seeking was self-protection she could herself use, and there was none.

Pregnancy was a chronic condition among the women of this class. Suggestions as to what to do for a girl who was "in trouble" or a married woman who was "caught" passed from mouth to mouth - herb teas, turpentine, steaming, rolling downstairs, inserting slippery elm, knitting needles, shoe-hooks.

(10) It was the death of Sadie Sachs that convinced Margaret Sanger to devote her life to making reliable contraceptive information available to women. She wrote about the death of this woman in her autobiography published in 1938.

Then one stifling mid-July day of 1912 I was summoned to a Grand Street tenement. My patient was a small, slight Russian Jewess, about twenty-eight years old, of the special cast of feature to which suffering lends a madonna-like expression. The cramped three-room apartment was in a sorry state of turmoil. Jake Sachs, a truck driver scarcely older than his wife, had come home to find the three children crying and her unconscious from the effects of a self-induced abortion. He had called the nearest doctor, who in turn had sent for me. Jake's earnings were trifling, and most of them had gone to keep the none-too-strong children clean and properly fed. But his wife's ingenuity had helped them to save a little, and this he was glad to spend on a nurse rather than have her go to a hospital.

The doctor and I settled ourselves to the task of fighting the septicemia. Never had I worked so fast, never so concentratedly.

Jake was more kind and thoughtful than many of the husbands I had encountered. He loved his children, and had always helped his wife wash and dress them. He had brought water up and carried garbage down before he left in the morning, and did as much as he could for me while he anxiously watched her progress.

After a fortnight Mrs. Sachs' recovery was in sight. As I was preparing to leave the fragile patient to take up her difficult life once more, she finally voiced her fears, "Another baby will finish me, I suppose?"

"It's too early to talk about that," I temporized.

But when the doctor came to make his last call, I drew him aside. "Mrs. Sachs is terribly worried about having another baby."

"She well may be," replied the doctor, and then he stood before her and said, "Any more such capers, young woman, and there'll be no need to send for me."

"I know, doctor," she replied timidly, "but," and she hesitated as though it took all her courage to say it, "what can I do to prevent it?"

The doctor was a kindly man, and he had worked hard to save her, but such incidents had become so familiar to him

that he-had long since lost whatever delicacy he might once have had. He laughed good-naturedly. "You want to have your cake and eat it too, do you? Well, it can't be done."

Then picking up his hat and bag to depart he said, "Tell Jake to sleep on the roof."

I glanced quickly to Mrs. Sachs. Even through my sudden tears I could see stamped on her face an expression of absolute despair. We simply looked at each other, saying no word until the door had closed behind the doctor. Then she lifted her thin, blue-veined hands and clasped them beseechingly. "He can't understand. He's only a man. But you do, don't you? Please tell me the secret, and I'll never breathe it to a soul. Please!"

What was I to do? I could not speak the conventionally comforting phrases which would be of no comfort. Instead, I made her as physically easy as I could and promised to come back in a few days to talk with her again.

Night after night the wistful image of Mrs. Sachs appeared before me. I made all sorts of excuses to myself for not going back. I was busy on other cases; I really did not know what to say to her or how to convince her of my own ignorance; I was helpless to avert such monstrous atrocities. Time rolled by and I did nothing.

The telephone rang one evening three months later, and Jake Sachs' agitated voice begged me to come at once; his wife was sick again and from the same cause. For a wild moment I thought of sending someone else, but actually, of course, I hurried into my uniform, caught up my bag, and started out. All the way I longed for a subway wreck, an explosion, anything to keep me from having to enter that home again. But nothing happened, even to delay me. I turned into the dingy doorway and climbed the familiar stairs once more. The children were there, young little things.

Mrs. Sachs was in a coma and died within ten minutes. I folded,her still hands across her breast, remembering how they had pleaded with me, begging so humbly for the knowledge which was her right. I drew a sheet over her pallid face. Jake was sobbing, running his hands through his hair and pulling it out like an insane person. Over and over again he wailed, "My God! My God! My God!"

I left him pacing desperately back and forth, and for hours I myself walked and walked and walked through the hushed streets. When I finally arrived home and let myself quietly in, all the household was sleeping. I looked out my window and down upon the dimly lighted city. Its pains and griefs crowded in upon me, a moving picture rolled before my eyes with photographic clearness: women writhing in travail to bring forth little babies; the babies themselves naked and hungry, wrapped in newspaper to keep them from the cold; six-year-old children with pinched, pale, wrinkled faces, old in concentrated wretchedness, pushed into gray and fetid cellars, crouching on stone floors, their small scrawny hands scuttling through rags, making lamp shades, artificial flowers; white coffins, black coffins, coffins, coffins interminably passing in never-ending succession. The scenes piled one upon another on another. I could bear it no longer.

As I stood there the darkness faded. The sun came up and threw its reflection over the house tops. It was the dawn of a new day in my life also. The doubt and questioning, the experimenting and trying, were now to be put behind me. I knew I could not go back merely to keeping people alive.

I went to bed, knowing that no matter what it might cost, I was finished with palliatives and superficial cures; I was resolved to seek out the root of evil, to do something to change the destiny of mothers whose miseries were vast as the sky.

(11) Crystal Eastman, Birth Control Review (January, 1918)

Whether other feminists would agree with me that the economic is the fundamental aspect of feminism, I don't know. But on this we are surely agreed, that Birth Control is an elementary essential in all aspects of feminism. Whether we are the special followers of Alice Paul, or Ruth Law, or Ellen Key, or Olive Schreiner, we must all be followers of Margaret Sanger. Feminists are not nuns. That should be established. We want to love and to be loved, and most of us want children, one or two at least. But we want our love to be joyous and free - not clouded with ignorance and fear. And we want our children to be deliberately, eagerly called into being, when we are at our best, not crowded upon us in times of poverty and weakness. We want this precious sex knowledge not just for ourselves, the conscious feminists; we want it for all the millions of unconscious feminists that swarm the earth, - we want it for all women.

(12) In July 1915, the American birth-control campaigner, Margaret Sanger, met Marie Stopes in London. She wrote about their meeting in her book My Fight for Birth Control (1931)

Marie Stopes was then writing a book, Married Love, which was to deal with the plain facts of marriage. She expected it to "electrify" England. She then explained to me that, owing to her previous unfortunate marriage she had no experience in matters of contraception nor any occasion to inform herself of their use. Could I tell her exactly what methods were used? I replied that it would give me the greatest pleasure to bring to her home such devices as I had in my possession. Accordingly, we met again the following week for dinner in her home, and inspected and discussed the French pessary which she stated she then saw for the first time. I gave her my own pamphlets, all of which contained contraceptive information.

(13) Sidney Clift, wrote a letter of protest to Marie Stopes about her suggestion in Married Love the married couple should consider using contraception.

Do you really think that my wife and I and our poverty-stricken friends (though none of us can afford to have more than two or three children) are sadly in need of such dirty advice as you offer? Is it a desire to put bank notes in your pocket that you wrote such stuff as Married Love?

(14) On 1st May 1924, a twenty-seven year old wife of a farm labourer wrote to Marie Stopes asking advice on how to stop having children. The woman was expecting her fourth child and her family had an income of £1 7s a week.

My children do not have enough to eat and I cannot buy boots for them to wear… I have got into trouble with the school, because my boy did not go, as I had no boots for him to wear. I wrote and told my mother but she cannot help me because my father has died and left her with three children still going to school. She says I must stop having children… Do you think it would be best if I leave my husband and go into the workhouse… so we don't have any more children? I have gone without food and have tried to win money but everything I try fails. If you can kindly advise me I would be very grateful.

(15) Dora Russell, The Tamarisk Tree (1975)

Marie Stopes had established the first birth control clinic in Britain; the whole question of informing women, especially those who were poor, about methods of contraception, began to be discussed. Early in 1923, Rose Witcop and Guy Aldred, both on the left politically, were selling cheaply a pamphlet by Margaret Sanger explaining about sex and contraception in terms which, it was thought, uneducated women could understand. The police seized the pamphlet for destruction as obscene. The report of this made me exceedingly angry, for I could not see why information which a middle-class woman could get from her doctor should be withheld from a poorer woman who might need it far more. Bertie agreed with me that we should take some action; I contacted Maynard Keynes, who agreed to go surety with me for an appeal.