Nicola Sacco

Nicola Sacco was born in the Italian town of Torremaggiore on 22nd April, 1891. He emigrated to the United States when he was seventeen. Sacco found work in a shoe factory in Stoughton, Massachusetts. He got married and started a family. Sacco also became involved in left-wing politics and at one anarchist gathering met Bartolomeo Vanzetti, an Italian immigrant working as a fish peddler in Plymouth. The two men became friends and often attended the same political meetings together.

Like many left-wing radicals, Sacco and Vanzetti were opposed to the First World War. They took part in protest meetings and in 1917, when the United States entered the war, they fled together to Mexico in order to avoid being conscripted into the United States Army. When the war was over the two men returned to the United States.

On 5th May, 1920, Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were arrested and interviewed about the murders of Frederick Parmenter and Alessandro Berardelli, in South Braintree. The men had been killed while carrying two boxes containing the payroll of a shoe factory. After Parmenter and Berardelli were shot dead, the two robbers took the $15,000 and got into a car containing several other men, and driven away.

Several eyewitnesses claimed that the robbers looked Italian. A large number of Italian immigrants were questioned but eventually the authorities decided to charge Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti with the murders. Although the two men did not have criminal records, it was argued that they had committed the robbery to acquire funds for their anarchist political campaign.

Fred H. Moore, a socialist lawyer, agreed to defend the two men. Eugene Lyons, a young journalist, carried out research for Moore. Lyons later recalled: "Fred Moore, by the time I left for Italy, was in full command of an obscure case in Boston involving a fishmonger named Bartolomeo Vanzetti and a shoemaker named Nicola Sacco. He had given me explicit instructions to arouse all of Italy to the significance of the Massachusetts murder case, and to hunt up certain witnesses and evidence. The Italian labor movement, however, had other things to worry about. An ex-socialist named Benito Mussolini and a locust plague of blackshirts, for instance. Somehow I did get pieces about Sacco and Vanzetti into Avanti!, which Mussolini had once edited, and into one or two other papers. I even managed to stir up a few socialist onorevoles, like Deputy Mucci from Sacco's native village in Puglia, and Deputy Misiano, a Sicilian firebrand at the extreme Left. Mucci brought the Sacco-Vanzetti affair to the floor of the Chamber of Deputies, the first jet of foreign protest in what was eventually to become a pounding international flood."

The trial started on 21st May, 1921. The main evidence against the men was that they were both carrying a gun when arrested. Some people who saw the crime taking place identified Vanzetti and Sacco as the robbers. Others disagreed and both men had good alibis. Vanzetti was selling fish in Plymouth while Sacco was in Boston with his wife having his photograph taken. The prosecution made a great deal of the fact that all those called to provide evidence to support these alibis were Italian immigrants.

Boston on the day the murders took place.

Vanzetti and Sacco were disadvantaged by not having a full grasp of the English language. Webster Thayer, the judge was clearly prejudiced against anarchists. The previous year, he rebuked a jury for acquitting anarchist Sergie Zuboff of violating the criminal anarchy statute. It was clear from some of the answers Vanzetti and Sacco gave in court that they had misunderstood the question. During the trial the prosecution emphasized the men's radical political beliefs. Vanzetti and Sacco were also accused of unpatriotic behaviour by fleeing to Mexico during the First World War.

Eugene Lyons has argued in his autobiography, Assignment in Utopia (1937): "Fred Moore was at heart an artist. Instinctively he recognized the materials of a world issue in what appeared to others a routine matter... When the case grew into a historical tussle, these men were utterly bewildered. But Moore saw its magnitude from the first. His legal tactics have been the subject of dispute and recrimination. I think that there is some color of truth, indeed, to the charge that he sometimes subordinated the literal needs of legalistic procedure to the larger needs of the case as a symbol of class struggle. If he had not done so, Sacco and Vanzetti would have died six years earlier, without the solace of martyrdom. With the deliberation of a composer evolving the details of a symphony which he senses in its rounded entirety, Moore proceeded to clarify and deepen the elements implicit in the case. And first of all he aimed to delineate the class character of the automatic prejudices that were operating against Sacco and Vanzetti. Sometimes over the protests of the men themselves he cut through legalistic conventions to reveal underlying motives. Small wonder that the pinched, dyspeptic judge and the pettifogging lawyers came to hate Moore with a hatred that was admiration turned inside out."

In court Sacco claimed: "I know the sentence will be between two classes, the oppressed class and the rich class, and there will be always collision between one and the other. We fraternize the people with the books, with the literature. You persecute the people, tyrannize them and kill them. We try the education of people always. You try to put a path between us and some other nationality that hates each other. That is why I am here today on this bench, for having been of the oppressed class. Well, you are the oppressor." The trial lasted seven weeks and on 14th July, 1921, both men were found guilty of first degree murder and sentenced to death.

The Sacco and Vanzetti Case received a great deal of publicity. Many observers believed that their conviction resulted from prejudice against them as Italian immigrants and because they held radical political beliefs. The case resulted in anti-US demonstrations in several European countries and at one of these in Paris, a bomb exploded killing twenty people.

In 1925 Celestino Madeiros, a Portuguese immigrant, confessed to being a member of the gang that killed Frederick Parmenter and Alessandro Berardelli. He also named the four other men, Joe, Fred, Pasquale and Mike Morelli, who had taken part in the robbery. The Morelli brothers were well-known criminals who had carried out similar robberies in area of Massachusetts. However, the authorities refused to investigate the confession made by Madeiros.

Many leading writers and artists such as John Dos Passos, Alice Hamilton, Paul Kellog, Jane Addams, Upton Sinclair, Dorothy Parker, Ben Shahn, Edna St. Vincent Millay, John Howard Lawson, Floyd Dell, George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells became involved in a campaign to obtain a retrial. Although Webster Thayer, the original judge, was officially criticised for his conduct at the trial, the authorities refused to overrule the decision to execute the men.

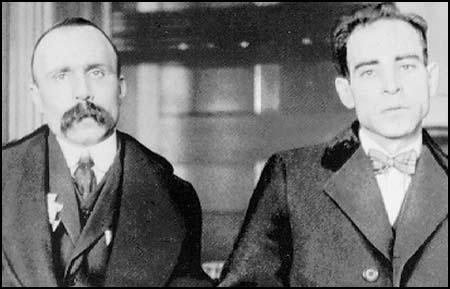

Eugene Lyons was a regular visitor to see Sacco in prison: "Sacco was the Latin at his most impetuous, a man of emotion rather than logic, driven literally to madness on at least two occasions by the ordeal of imprisonment and waiting. The separation from his pretty red-headed wife and his two children, from friends and work, consumed his flesh and shook his reason. A week of incarceration for a man like Sacco was more terrible than a year for the more phlegmatic and contemplative Vanzetti. Sacco was a caged and raging animal; Vanzetti seemed a monk in calm seclusion. Under the ferocious Italian mustaches which gave him a look of fierceness in the eyes of the ordinary American, the fishmonger from Piemonte had ascetic features and eyes of a tenderness that haunted one."

By the summer of 1927 it became clear that Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti would be executed. Vanzetti commented to a journalist: "If it had not been for this thing, I might have lived out my life talking at street corners to scorning men. I might have died, unmarked, unknown, a failure. Now we are not a failure. This is our career and our triumph. Never in our full life can we hope to do such work for tolerance, justice, for man's understanding of man, as now we do by accident. Our words - our lives - our pains - nothing! The taking of our lives - lives of a good shoemaker and a poor fish peddler - all! That last moment belong to us - that agony is our triumph. On 23rd August 1927, the day of execution, over 250,000 people took part in a silent demonstration in Boston.

Soon after the executions Eugene Lyons published his book, The Life and Death of Sacco and Vanzetti (1927): "It was not a frame-up in the ordinary sense of the word. It was a far more terrible conspiracy: the almost automatic clicking of the machinery of government spelling out death for two men with the utmost serenity. No more laws were stretched or violated than in most other criminal cases. No more stool-pigeons were used. No more prosecution tricks were played. Only in this case every trick worked with a deadly precision. The rigid mechanism of legal procedure was at its most unbending. The human beings who operated the mechanism were guided by dim, vague, deep-seated motives of fear and self-interest. It was a frame-up implicit in the social structure. It was a perfect example of the functioning of class justice, in which every judge, juror, police officer, editor, governor and college president played his appointed role easily and without undue violence to his conscience. A few even played it with an exalted sense of their own patriotism and nobility."

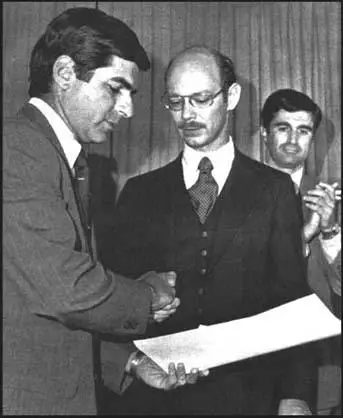

Fifty years later, on 23rd August, 1977, Michael Dukakis, the Governor of Massachusetts, issued a proclamation, effectively absolving the two men of the crime."Today is the Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti Memorial Day. The atmosphere of their trial and appeals were permeated by prejudice against foreigners and hostility toward unorthodox political views. The conduct of many of the officials involved in the case shed serious doubt on their willingness and ability to conduct the prosecution and trial fairly and impartially. Simple decency and compassion, as well as respect for truth and an enduring commitment to our nation's highest ideals, require that the fate of Sacco and Vanzetti be pondered by all who cherish tolerance, justice and human understanding."

Primary Sources

(1) Nicola Sacco, statement to court after being sentenced to death (9th April, 1927)

I am no orator. It is not very familiar with me the English language, and as I know, as my friend has told me, my comrade Vanzetti will speak more long, so I thought to give him the chance.

I never knew, never heard, even read in history anything so cruel as this Court. After seven years prosecuting they still consider us guilty. And these gentle people here are arrayed with us in this court today.

I know the sentence will be between two classes, the oppressed class and the rich class, and there will be always collision between one and the other. We fraternize the people with the books, with the literature. You persecute the people, tyrannize them and kill them. We try the education of people always. You try to put a path between us and some other nationality that hates each other. That is why I am here today on this bench, for having been of the oppressed class. Well, you are the oppressor.

You know it, Judge Thayer - you know all my life, you know why I have been here, and after seven years that you have been persecuting me and my poor wife, and you still today sentence us to death. I would like to tell all my life, but what is the use? You know all about what I say before, that is, my comrade, will be talking, because he is more familiar with the language, and I will give him a chance.

You forget all this population that has been with us for seven years, to sympathize and give us all their energy and all their kindness. You do not care for them. Among that peoples and the comrades and the working class there is a big legion of intellectual people which have been with us for seven years, to not commit the iniquitous sentence, but still the Court goes ahead. And I want to thank you all, you peoples, my comrades who have been with me for seven years, with the Sacco Vanzetti case, and I will give my friend a chance.

(2) Bartolomeo Vanzetti, comments about Nicola Sacco (9th April, 1927)

Sacco is a worker from his boyhood, a skilled worker lover of work, with a good job and pay, a bank account, a good and lovely wife, two beautiful children and a neat little home at the verge of a wood, near a brook. Sacco is a heart, a faith, a character, a man; a man lover of nature and of mankind. A man who gave all, who sacrifice all to the cause of Liberty and to his love for mankind; money, rest, mundane ambitions, his own wife, his children, himself and his own life. Sacco has never dreamt to steal, never to assassinate. He and I have never brought a morsel of bread to our mouths, from our childhood to today--which has not been gained by the sweat of our brows. Never. His people also are in good position and of good reputation.

Oh, yes, I may be more witfull, as some have put it, I am a better babbler than he is, but many, many times in hearing his heartful voice ringing a faith sublime, in considering his supreme sacrifice, remembering his heroism I felt small small at the presence of his greatness and found myself compelled to fight back from my eyes the tears, and quench my heart troubling to my throat to not weep before him--this man called thief and assassin and doomed. But Sacco's name will live in the hearts of the people and in their gratitude when Katzmann's and yours bones will be dispersed by time, when your name, his name, your laws, institutions, and your false god are but a deem remembering of a cursed past in which man was wolf to the man.

(3) Eugene Lyons, Assignment in Utopia (1937)

Sacco was the Latin at his most impetuous, a man of emotion rather than logic, driven literally to madness on at least two occasions by the ordeal of imprisonment and waiting. The separation from his pretty red-headed wife and his two children, from friends and work, consumed his flesh and shook his reason. A week of incarceration for a man like Sacco was more terrible than a year for the more phlegmatic and contemplative Vanzetti. Sacco was a caged and raging animal; Vanzetti seemed a monk in calm seclusion. Under the ferocious Italian mustaches which gave him a look of fierceness in the eyes of the ordinary American, the fishmonger from Piemonte had ascetic features and eyes of a tenderness that haunted one.

(4) Michael Dukakis, Governor of Massachusetts, proclamation on the Sacco and Vanzetti case (23rd August, 1977)

Today is the Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti Memorial Day. The atmosphere of their trial and appeals were permeated by prejudice against foreigners and hostility toward unorthodox political views. The conduct of many of the officials involved in the case shed serious doubt on their willingness and ability to conduct the prosecution and trial fairly and impartially. Simple decency and compassion, as well as respect for truth and an enduring commitment to our nation's highest ideals, require that the fate of Sacco and Vanzetti be pondered by all who cherish tolerance, justice and human understanding.