Anarchism

Anarchism is the political belief that society should have no government, laws, police, or other authority, but should be a free association of all its members. William Godwin, an important anarchist philosopher in Britain during the late 18th century, believed that the "euthanasia of government" would be achieved through "individual moral reformation".

In 1840 Pierre-Joseph Proudhon published What is Property? In the book Proudhon attacks the injustices of inequality and coined the phrase, "property is theft". Proudhon contrasted the right of property with the rights of liberty, equality, and security, saying: "The liberty and security of the rich do not suffer from the liberty and security of the poor; far from that, they mutually strengthen and sustain each other. The rich man’s right of property, on the contrary, has to be continually defended against the poor man’s desire for property."

In 1842 Proudhon was arrested for his radical political views but was acquitted in court. The following year he joined the Lyons Mutualists, a secret society of working men. The group discussed ways of achieving a more egalitarian society and during this period Proudhon developed the theory of Mutualism where small groups worked together and credit was made available through a People's Bank.

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon published his most important work, System of Economic Contradictions, was published in 1846. Karl Marx responded to Proudhon's book by writing The Poverty of Philosophy (1847). This was the beginning of the long-term struggle of ideas between the two men. Proudhon was opposed to Marx's authoritarianism and his main influence was on the libertarian socialist movement.

After the 1848 French Revolution in France, Proudhon was elected to the National Assembly. This experience resulted in the publication of Confessions of a Revolutionary (1849) and the General Idea of the Revolution in the 19th Century (1851). In these books Proudhon criticized representative democracy and argued that in reality political authority is exercised by only a small number of people. In 1854 Proudhon contracted cholera. He survived but he never fully recovered his health. Over the next few years Michael Bakunin became the most important anarchist writer.

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon published the Principle of Federation in 1863. In the book he argued that nationalism inevitably leads to war. To reduce the power of nationalism Proudhon called for a Federal Europe. Proudhon believed that Federalism was "the supreme guarantee of all liberty and of all law, and must, without soldiers or priests, replace both feudal and Christian society." Proudhon went on to predict that "the twentieth century will open the era of federations, or humanity will begin again a purgatory of a thousand years."

The ideas of Proudhon and Bakunin spread to the United States. William Greene, a former officer in the Union Army, joined with Ezra Heywood and Josiah Warren to develop America's first anarchist movement. Greene became increasingly involved in the struggle for trade union rights and became president of the Massachusetts Labor Union.

The International Working Men's Association was established in 1864. The IWMA (also known as the First International) was federation of radical political parties that hoped to overthrow capitalism and create a socialist commonwealth. In the organization Proudhon's followers clashed with those of Karl Marx and Mikhail Bakunin. Proudhon, unlike the other two men, believed socialism was possible without the need for a violent revolution.

In March 1869 Michael Bakunin met Sergi Nechayev Soon afterwards Bakunin wrote to James Guillaume that: "I have here with me one of those young fanatics who know no doubts, who fear nothing, and who realize that many of them will perish at the hands of the government but who nevertheless have decided that they will not relent until the people rise. They are magnificent, these young fanatics, believers without God, heroes without rhetoric."

In 1869 Bakunin and Nechayev co-wrote Catechism of a Revolutionist. It included the famous passage: "The Revolutionist is a doomed man. He has no private interests, no affairs, sentiments, ties, property nor even a name of his own. His entire being is devoured by one purpose, one thought, one passion - the revolution. Heart and soul, not merely by word but by deed, he has severed every link with the social order and with the entire civilized world; with the laws, good manners, conventions, and morality of that world. He is its merciless enemy and continues to inhabit it with only one purpose - to destroy it."

In August, 1869, Sergi Nechayev returned to Russia and settled in Moscow where he set up a secret terrorist organization, People's Retribution. When one of its members, Ivan Ivanovich Ivanov, questioned Nechayev's political ideas, he murdered him. The body was weighted down with stones and dumped through an ice hole in a nearby pond. He told the rest of the group, "the ends justify the means".

Nechayev escaped from Moscow but after discovering the body, some three hundred revolutionaries were arrested and imprisoned. Nechayev arrived in Locarno, where Michael Bakunin was living, in January 1870. At first Bakunin was pleased to see Nechayev but the relationship soon deteriorated. According to Z.K. Ralli, Nechayev no longer showed any deference to his mentor. Nechayev told friends that Bakunin had lost the "level of energy and self-abnegation" required to be a true revolutionary. Bakunin wrote that: "If you introduce him to a friend, he will immediately proceed to sow dissension, scandal, and intrigue between you and your friend and make you quarrel. If your friend has a wife or a daughter, he will try to seduce her and get her with child in order to snatch her from the power of conventional morality and plunge her despite herself into revolutionary protest against society."

German Lopatin arrived from Russia with news that Sergi Nechayev was responsible for the murder of Ivan Ivanovich Ivanov. Mikhail Bakunin wrote to Nechayev: "I had complete faith in you, while you duped me. I turned out to be a complete fool. This is painful and shameful for a man of my experience and age. Worse than this, I spoilt my situation with regard to the Russian and International causes."

Bakunin completely disagreed with Nechayev's approach to anarchism which he called his "false Jesuit system". He argued that the popular revolution must be "invisibly led, not by an official dictatorship, but by a nameless and collective one, composed of those in favour of total people's liberation from all oppression, firmly united in a secret society and always and everywhere acting in support of a common aim and in accordance with a common program." He added: "The true revolutionary organization does not foist upon the people any new regulations, orders, styles of life, but merely unleashes their will and gives wide scope to their self-determination and their economic and social organization, which must be created by themselves from below and not from above.... The revolutionary organization must make impossible after the popular victory the establishment of any state power over the people - even the most revolutionary, even your power - because any power, whatever it calls itself, would inevitably subject the people to old slavery in new form."

Mikhail Bakunin told Sergi Nechayev: "You are a passionate and dedicated man. This is your strength, your valor, and your justification. If you alter your methods, I would wish not only to remain allied with you, but to make this union even closer and firmer." He wrote to N. P. Ogarev that: "The main thing for the moment is to save our erring and confused friend. In spite of all, he remains a valuable man, and there are few valuable men in the world.... We love him, we believe in him, we foresee that his future activity will be of immense benefit to the people. That is why we must divert him from his false and disastrous path."

Nechayev rejected Bakunin's views and in the summer of 1870 he moved to London where he published a new journal called The Commune. This venture ended in failure and he eventually returned to Switzerland where he found work as a sign-painter. On 14th August, 1872, Nechayev was arrested in Zurich and was extradited to Russia. Nechayev was tried for the murder of Ivan Ivanovich Ivanov. He said in court "I refuse to be a slave of your tyrannical government. I do not recognize the Emperor and the laws of this country." He would not answer any questions and was finally dragged from the dock shouting: "Down with despotism!" He was found guilty and sentenced to twenty years' hard labour and sent to the Peter and Paul Fortress in St. Petersburg.

Mikhail Bakunin was accused of anarchism and in 1872 he was expelled from the First International. The following year Bakunin published his major work, Statism and Anarchy. In the book Bakunin advocated the abolition of hereditary property, equality for women and free education for all children. He also argued for the transfer of land to agricultural communities and factories to labour associations.

In 1872 Peter Kropotkin joined a group that was spreading revolutionary propaganda among the workers and peasants of Moscow and St. Petersburg. In 1874 he was arrested and imprisoned. Two years later he escaped and fled to Switzerland. After the assassination of Tsar Alexander II his radical socialist views made him unwelcome in the country and in 1881 he moved to France where he became a member of the International Working Men's Association. Kropotkin became interested in the work of Charles Darwin. He had profound respect for Darwin's discoveries and regarded the theory of natural selection as "perhaps the most brilliant scientific generalization of the century". Kropotkin accepted that the "struggle for existence" played an important role in the evolution of species. He argued that "life is struggle; and in that struggle the fittest survive". However, Kropotkin rejected the ideas of Thomas Huxley who placed great emphasis on competition and conflict in the evolutionary process.

William Greene introduced Benjamin Tucker to Ezra Heywood and Josiah Warren. All three men were supporters of Mikhail Bakunin who at that time was living in Switzerland. Tucker became a convert and wrote: "We are willing to hazard the judgment that coming history will yet place him (Bakunin) in the very front ranks of the world's great social saviours. The grand head and face speak for themselves regarding the immense energy, lofty character, and innate nobility of the man. We should have esteemed it among the chief honors of our life to have known him personally, and should account it a great piece of good fortune to talk with one who was personally intimate with him and the essence and full meaning of his thought and aspiration."

Benjamin Tucker spoke several languages and was an accomplished translator. After reading the work of Pierre Joseph Proudhon he published the first English edition of What is Property. Over the next few years he translated the work of Mikhail Bakunin, Peter Kropotkin, Victor Hugo, Nikolai Chernyshevsky and Leo Tolstoy.

In 1880 Peter Kropotkin read an article by Karl Kessler, a Russian zoologist, entitled On the Law of Mutual Aid. Kessler's argued that cooperation rather than conflict was the chief factor in the process of evolution. He pointed out "the more individuals keep together, the more they mutually support each other, and the more are the chances of the species for surviving, as well as for making further progress in its intellectual development." Kessler died the following year and Kropotkin decided to spend time developing his theories.

Kropotkin published An Appeal to the Young in 1880. Anna Strunsky wrote that "hundreds of thousands had read that pamphlet and had responded to it as to nothing else in the literature of revolutionary socialism". Elizabeth Gurley Flynn later claimed that the message "struck home to me personally, as if he were speaking to us there in our shabby poverty-stricken Bronx flat."

Benjamin Tucker founded the anarchist journal, Liberty in 1881. In the first edition Tucker praised Sophie Perovskaya, the Russian revolutionary who had just been executed for taking part in the assassination of Tsar Alexander II. He was also the author of State Socialism and Anarchism (1899). Paul Avrich has argued: "It (Liberty) was meticulously designed and edited, with brilliant galaxy of contributors, not least among them Tucker himself. Its debut in 1881 was a milestone in the history of the anarchist movement, and it won an audience wherever English was read. As a publisher, moreover, Tucker issued a steady stream of books and pamphlets on anarchism and related subjects over a period of nearly thirty years."

In 1883 Peter Kropotkin was arrested by the French authorities. He tried at Lyon, and sentenced, under a special law passed on the fall of the Paris Commune, to five years' imprisonment, on the ground that he had belonged to the International Working Men's Association. While in prison Kropotkin's first ideas on anarchism were published. His ideas spread all over the world.

Anarchists were blamed for the Haymarket Bombing in Chicago on 4th May, 1886. The authorities were unable to identify the person who threw the bomb but a group of anarchists, Albert Parsons, August Spies, Adolph Fisher, Louis Lingg and George Engel, who helped organized the meeting, were sentenced to death for "conspiracy to murder".

Peter Kropotkin continued to develop his ideas on evolution. In 1888 Thomas Huxley published an article entitled The Struggle for Existence. He completely rejected Huxley's argument that competition among individuals of the same species is not merely a law of nature but the driving force of progress. Kropotkin replied to Huxley in a series of articles where he documented his theory of mutual aid with illustrations from animal and human life. Paul Avrich has argued: "Among animals he shows how mutual cooperation is practiced in hunting, in migration, and in the propagation of species. He draws examples from the elaborate social behavior of ants and bees, from wild horses that form a ring when attacked by wolves, from the wolves themselves that form a pack for hunting, from migrating deer that, scattered over a wide territory, come together in herds to cross a river. From these and many similar illustrations Kropotkin demonstrates that sociability is a prevalent feature at every level of the animal world. Moreover, he finds that among humans too mutual aid has been the rule rather than the exception. With a wealth of data he traces the evolution of voluntary cooperation from the primitive tribe, peasant village, and medieval commune to a variety of modern associations that have continued to practice Mutual support despite the rise of the coercive bureaucratic state. His thesis, in short, is a refutation of the doctrine that competition and brute force are the sole - or even the principal - determinants of social progress."

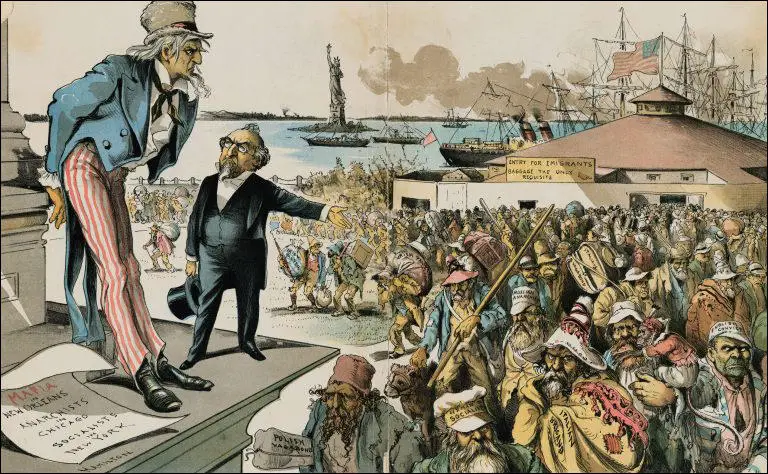

would no longer be troubled with Anarchy, Socialism, the Mafia and such kindred evils!” (1891)

.

In 1892 the Russian anarchist, Alexander Berkman, attempted to murder William Frick. Another immigrant, Gaetano Bresci, returned to Italy and assassinated King Umberto. Soon afterwards, another anarchist Leon Czolgosz, assassinated President William McKinley.

Other anarchists like Kropotkin were totally against the use of violence. In 1892 published Conquest of Bread. It is generally agreed that the book is Kropotkin's clearest statement of his anarchist social doctrines. As Paul Avrich has pointed out: "Written for the ordinary worker, it possesses a lucidity of style not often found in books on social themes." Emile Zola said that it was so well-written that it was a "true poem".

Kropotkin argued that the wage system, which presumes to measure the work of each individual in capitalism, must be abolished in favour of a system of equal rewards for all. Kropotkin suggested a system of "anarchist communism" by which private property and inequality of income would give place to the free distribution of goods and services. The author of Anarchist Portraits (1995) argued: "It was impossible to assess each person's contribution to the production of social wealth because millions of human beings had toiled to create the present riches of the world. Every acre of soil had been watered with the sweat of generations, every mile of railroad had received its share of human blood. Indeed, there was not a thought or an invention that was not the common inheritance of all mankind... Starting from this premise, Kropotkin argues that the wage system, which presumes to measure the work of each individual, must be abolished in favor of a system of equal rewards for all. This was a major step in the evolution of anarchist economic thought."

In Conquest of Bread Kropotkin argued that in an anarchist society no one would be compelled to work. He insisted that work is "a psychological necessity, a necessity of spending accumulated body energy, a necessity which is health and life itself. If so many) branches of useful work are reluctantly done now, it is merely because they mean overwork or they are improperly organized."

Peter Kropotkin rejected the idea of a secret revolutionary party that had been suggested by Mikhail Bakunin. He also criticized the views of Sergi Nechayev. He insisted that social emancipation must be attained by libertarian rather than dictatorial means. Kropotkin rejected the idea of revolution put forward by Bakunin and Nechayev in Catechism of a Revolutionist (1869): "The Revolutionist is a doomed man. He has no private interests, no affairs, sentiments, ties, property nor even a name of his own. His entire being is devoured by one purpose, one thought, one passion - the revolution. Heart and soul, not merely by word but by deed, he has severed every link with the social order and with the entire civilized world; with the laws, good manners, conventions, and morality of that world. He is its merciless enemy and continues to inhabit it with only one purpose - to destroy it." For Kropotkin the ends and the means were inseparable.

In October 1897, Peter Kropotkin crossed the border into the United States to meet fellow anarchist, Johann Most. Although they had disagreed in the past about politics, Kropotkin argued that "with a few more Mosts, our movement would be much stronger". Writing in the Freiheit Most described Kropotkin as the "celebrated philosopher of modern anarchism" and that it had been a pleasure "to look into his eyes and shake his hand".

At Jersey City he was asked by a group of journalists for a statement on his political beliefs: "I am an anarchist and am trying to work out the ideal society, which I believe will be communistic in economics, but will leave full and free scope for the development of the individual. As to its organization, I believe in the formation of federated groups for production and consumption.... The social democrats are endeavoring to attain the same end, but the difference is that they start from the centre - the State and work toward the circumference, while we endeavor to work out the ideal society from the simple elements to the complex."

The New York Herald reported: "Prince Kropotkin is anything but the typical anarchist. In appearance he is patriarchal, and while his dress is careless it is the carelessness of the man who is engrossed in science rather than that of the man who is in revolt against the usages of society. His manners are those of the polished gentleman, and he has none of the bitterness and dogmatism of the anarchist whom we are accustomed to see here."

After the overthrow of the Tsar Nicholas II in 1917, Peter Kropotkin returned home to Russia expecting the development of "anarchist communism". When the Bolsheviks seized power he remarked to a friend that "this buries the revolution" and described government members as "state socialists". In June 1918, Kropotkin had a meeting with Nestor Makhno, the leader of the anarchists in the Ukraine. He told him about a conversation he had with Lenin in the Kremlin. Lenin explained his opposition to anarchists. "The majority of anarchists think and write about the future without understanding the present. That is what divides us Communists from them... But I think that you, comrade, have a realistic attitude towards the burning evils of the time. If only one-third of the anarchist-communists were like you, we Communists would be ready, under certain well-known conditions, to join with them in working towards a free organization of producers."

Kropotkin disliked the developments that took place over the next few months and in March 1920 he sent a letter to Lenin that claimed Russia was a "Soviet Republic only in name" and "at present it is not the soviets which rule in Russia but party committees".

In 1919 Woodrow Wilson appointed A. Mitchell Palmer as his attorney general. Soon after taking office, a government list of 62 people believed to hold "dangerous, destructive and anarchistic sentiments" was leaked to the press. It was also revealed that these people had been under government surveillance for many years. Worried by the revolution that had taken place in Russia, Palmer became convinced that Communist agents were planning to overthrow the American government. Palmer recruited John Edgar Hoover as his special assistant and together they used the Espionage Act (1917) and the Sedition Act (1918) to launch a campaign against radicals and left-wing organizations.

Palmer claimed that Communist agents from Russia were planning to overthrow the American government. On 7th November, 1919, the second anniversary of the Russian Revolution, over 10,000 suspected communists and anarchists were arrested. Palmer and Hoover found no evidence of a proposed revolution but large number of these suspects were held without trial for a long time. The vast majority were eventually released but Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, Mollie Steimer, and 245 other people, were deported to Russia.

In January 1920 Berkman and Goldman toured Russia collecting material for the Museum of the Revolution in Petrograd. However, Lenin was a strong opponent of anarchism. He told Nestor Makhno, the most important anarchist in Russia: "The majority of anarchists think and write about the future without understanding the present. That is what divides us Communists from them."

A pact with the anarchists for joint military action against General Anton Denikin and his White Army was signed in March 1919. However, the Bolsheviks did not trust the anarchists and two months later two Cheka agents sent to assassinate Nestor Makhno were caught and executed. Leon Trotsky, commander-in-chief of the Bolsheviks forces, ordered the arrest of Makhno and sent in troops to Hulyai-Pole dissolve the agricultural communes set up by the Makhnovists. With Makhno's power undermined, a few days later, Denikin forces arrived and completed the job, liquidating the local soviets as well. In September, 1919, the Red Army was able to force Denikin's army to retreat to the shores of the Black Sea.

Leon Trotsky now turned to dealing with the anarchists and outlawed the Makhnovists. According to the author of Anarchist Portraits (1995): "There ensued eight months of bitter struggle, with losses heavy on both sides. A severe typhus epidemic augmented the toll of victims. Badly outnumbered, Makhno's partisans avoided pitched battles and relied on the guerrilla tactics they had perfected in more than two years of civil war."

Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, who had already been appalled by the way that Lenin and Trotsky had dealt with the Kronstadt Uprising decided to leave Russia. Berkman wrote: "Grey are the passing days. One by one the embers of hope have died out. Terror and despotism have crushed the life born in October. The slogans of the Revolution are forsworn, its ideals stifled in the blood of the people. The breath of yesterday is dooming millions to death; the shadow of today hangs like a black pall over the country. Dictatorship is trampling the masses under foot. The Revolution is dead; its spirit cries in the wilderness.... I have decided to leave Russia." After a brief stay in Stockholm, he lived in Berlin, where he published several pamphlets and books on the Bolshevik government, including The Bolshevik Myth (1925).

Emma Goldman's books, My Disillusionment in Russia (1923) and My Further Disillusionment in Russia (1924) helped to turn a large number of socialists against the Bolshevik government. Lincoln Steffens, who had famously said on arriving back from Russia after the revolution: "I have been over into the future, and it works." He admitted that "it was harder on the real reds than it was on us liberals. Emma Goldman, the anarchist who was deported to that socialist heaven, came out and said it was hell. And the socialists, the American, English, the European socialists, they did not recognize their own heaven. As some will put it, the trouble with them was that they were waiting at a station for a local train, and an express tore by and left them there. My summary of all our experiences was that it showed that heaven and hell are one place, and we all go there. To those who are prepared, it is heaven; to those who are not fit and ready, it is hell."

In 1926 Nestor Makhno joined forces broke with Peter Arshinov to publish their controversial Organizational Platform, which called for a General Union of Anarchists. This was opposed by Emma Goldman, Vsevolod Volin, Alexander Berkman, Sébastien Faure and Rudolf Rocker, who argued that the idea of a central committee clashed with the basic anarchist principle of local organisation.

In the first few weeks of the Spanish Civil War an estimated 100,000 men joined Anarcho-Syndicalists militias. Anarchists also established the Iron Column, many of whose 3,000 members were former prisoners. In Guadalajara, Cipriano Mera, leader of the CNT construction workers in Madrid, formed the Rosal Column. The most important anarchist leader of this period was Buenaventura Durruti who was killed while fighting in Madrid on 20th November 1936. Durruti's supporters in the CNT claimed that he had been murdered by members of the Communist Party (PCE).

In September 1936, President Manuel Azaña appointed the left-wing socialist, Francisco Largo Caballero as prime minister. Largo Caballero also took over the important role of war minister. Largo Caballero brought into his government four anarchist leaders, Juan Garcia Oliver (Justice), Juan López (Commerce), Federica Montseny (Health) and Juan Peiró (Industry). Montseny was the first woman in Spanish history to be a cabinet minister. Over the next few months Montseny accomplished a series of reforms that included the introduction of sex education, family planning and the legalization of abortion.

Anarchism enjoyed a mild revival in the United States after the Second World War. This included writers such as Dorothy Day, who published The Catholic Worker, and Dwight Macdonald, the editor of Politics. Paul Goodman also had considerable success with Growing Up Absurd (1961).

Murray Bookchin was probably the most most important anarchist writing in the second-half of the 20th century. Bookchin published a series of books on social ecology including Post-Scarcity Anarchism (1971), The Limits of the City (1973) and Toward an Ecological Society (1980). In The Ecology of Freedom: The Emergence and Dissolution of Hierarchy (1982), Bookchin argues that "If we do not do the impossible, we shall be faced with the unthinkable."

Bookchin argued that capitalism had to be overthrown: "The notion that man must dominate nature emerges directly from the domination of man by man… But it was not until organic community relation… dissolved into market relationships that the planet itself was reduced to a resource for exploitation. This centuries-long tendency finds its most exacerbating development in modern capitalism. Owing to its inherently competitive nature, bourgeois society not only pits humans against each other, it also pits the mass of humanity against the natural world. Just as men are converted into commodities, so every aspect of nature is converted into a commodity, a resource to be manufactured and merchandised wantonly.… The plundering of the human spirit by the market place is paralleled by the plundering of the earth by capital."

According to John P. Clark, the author of The Anarchist Moment: Reflections on Culture, Nature and Power (1984): "Bookchin's work continued to evolve in the 1980s. He developed a theory of libertarian municipalism, a full-scale critique of nature philosophy, and the defense of radical ecology within the Green movement." Other books on social ecology included The Modern Crisis (1986) and The Rise of Urbanization and the Decline of Citizenship (1987). In Remaking Society (1990) Bookchin argues that capitalism cannot solve these environmental problems. He attacks the idea of green capitalism and points out that "capitalism can no more be persuaded to limit growth than a human being can be persuaded to stop breathing."

In his later life Murray Bookchin became increasingly disillusioned with anarchism. In the 1990s he began to argue that social ecology was a new form of libertarian socialism and was part of the framework of communalism. According to Janet Biehl in a 2002 essay "he rejected anarchism altogether in favor of communalism, an equally anti-statist doctrine that he felt to be more explicitly oriented than anarchism to social rather than to individual liberation."

Primary Sources

(1) Mikhail Bakunin and Sergi Nechayev, Catechism of a Revolutionist (1869)

The Revolutionist is a doomed man. He has no private interests, no affairs, sentiments, ties, property nor even a name of his own. His entire being is devoured by one purpose, one thought, one passion - the revolution. Heart and soul, not merely by word but by deed, he has severed every link with the social order and with the entire civilized world; with the laws, good manners, conventions, and morality of that world. He is its merciless enemy and continues to inhabit it with only one purpose - to destroy it.

He despises public opinion. He hates and despises the social morality of his time, its motives and manifestations. Everything which promotes the success of the revolution is moral, everything which hinders it is immoral. The nature of the true revolutionist excludes all romanticism, all tenderness, all ecstasy, all love.

(2) Mikhail Bakunin, Marxism, Freedom and the State (1871)

I am a passionate seeker after Truth and a not less passionate enemy of the malignant fictions used by the "Party of Order", the official representatives of all turpitudes, religious, metaphysical, political, judicial, economic, and social, present and past, to brutalise and enslave the world; I am a fanatical lover of Liberty; considering it as the only medium in which can develop intelligence, dignity, and the happiness of man; not official "Liberty", licensed, measured and regulated by the State, a falsehood representing the privileges of a few resting on the slavery of everybody else; not the individual liberty, selfish, mean, and fictitious advanced by the school of Rousseau and all other schools of bourgeois Liberalism, which considers the rights of the individual as limited by the rights of the State, and therefore necessarily results in the reduction of the rights of the individual to zero.

No, I mean the only liberty which is truly worthy of the name, the liberty which consists in the full development of all the material, intellectual and moral powers which are to be found as faculties latent in everybody, the liberty which recognises no other restrictions than those which are traced for us by the laws of our own nature; so that properly speaking there are no restrictions, since these laws are not imposed on us by some outside legislator, beside us or above us; they are immanent in us, inherent, constituting the very basis of our being, material as well as intellectual and moral; instead, therefore, of finding them a limit, we must consider them as the real conditions and effective reason for our liberty.

(3) Statement issued at an Anarchist Congress at Pittsburgh (1883)

All laws are directed against the working people. Even the school serves only the purpose of furnishing the offspring of the wealthy with those qualities necessary to uphold their class domination. The children of the poor get scarcely a formal elementary training, and this, too, is mainly directed to such branches as tend to producing prejudices, arrogance, and servility; in short, want of sense. The Church finally seeks to make complete idiots out of the mass and to make them forego the paradise on earth by promising a fictitious heaven. The capitalist press, on the other hand, takes care of the confusion of spirits in public life. The workers can therefore expect no help from any capitalistic party in their struggle against the existing system. They must achieve their liberation by their own efforts. As in former times, a privileged class never surrenders its tyranny, neither can it be expected that the capitalists of this age will give up their rulership without being forced to do it.

(4) Michael Schwab, speech at his trial for the Haymarket Bombing (September, 1887)

According to our vocabulary Anarchy is a state of society in which the only government is reason; a state of society in which all human beings do right for the simple reason that it is right, and hate wrong because it is wrong. In such a society no compulsion will be necessary. Anarchy is a dream, but only in the present. It is entirely wrong to use the word Anarchy as synonymous with violence. Violence is something, and Anarchy is another. In the present state of society violence is used on all sides, and therefore we advocated the use of violence against violence, but against violence only as a necessary means of defense.

(5) George Engel, speech at his trial (September, 1887)

Anarchism and Socialism are, according to my opinion, as like as one egg is to another. Only the tactics are different. Therefore, I say to the working classes, do not believe any longer in the ballot-box and in those ways and means that are open to you; but rather think about ways and means when the time comes, when the burden of the people becomes intolerable. And that is our crime. Because we have named to the people the ways and means by which they could free themselves in the fight against Capitalism, by reason of that, Anarchism is hated and persecuted in every state.

(6) Samuel Jones, the successful businessman and four-term mayor of Toledo, Ohio, was one of the first to try and introduce socialist ideas to local government. In his article, The New Patriotism: A Golden-Rule Government for Cities, he quoted Henry Demarest Lloyd on the subject of anarchy.

The ethics of the wild beast, the survival of the strongest, shrewdest, and meanest, have been the inspiration of our materialistic lives during the last quarter or half century. The fact in our national history has brought us today face to face with the inevitable result. We have cities in which a few are wealthy, a few are in what may be called comfortable circumstances, vast numbers are propertyless, and thousands are in pauperism and crime. Certainly, no reasonable person will contend that this is the goal that we have been struggling for; that the inequalities that characterize our rich and poor represent the idea that the founders of this republic saw when they wrote that "All men are created equal."

The competitive idea at present dominant is most of our political and business life is, of course, the seed root of all the trouble. The people are beginning to understand that we have been pursuing a policy of plundering ourselves, that in the foolish scramble to make individuals rich we have been making all poor. "For a hundred years or so," says Henry Demarest Lloyd, "our economic theory has been one of industrial government by the self-interest of the individual; political government by the self-interest of the individual we call anarchy." It is one of the paradoxes of public opinion that the people of America, least tolerant of this theory of anarchy in political government, lead in practicing it in industry.

(7) Lyman Abbott, The Cause and Cure of Anarchism (Outlook, 22nd February, 1902)

Anarchism is defined by E. V. Zenker as: "the perfect, unfettered self-government of the individual, and consequently the absence of any kind of external government." It rests upon the doctrine that no man has a right to control by force the action of any other man. Anarchism is defended on historic grounds: the evils are recited which have been wrought in human history by the employment of force compelling obedience by one will to another will, as they are seen in political and religious despotism and in the subjugation of women.

Anarchism is defended on religious grounds. Jesus Christ is cited as the first of anarchists; for did he not say, "Resist not evil: if one take away thy coat, give him thy cloak also; and if one smite thee upon the one cheek, turn to him the other also? What is this, we are asked, but a denial of the right to use force even in defense of one's simplest and plainest rights?

Socialism, which is curiously confounded by the indiscriminating with anarchism, is its exact opposite. Anarchy is the doctrine that there should be no government control; socialism is the doctrine that the government should control everything.

The place in which to attack anarchism is where the offences grow which alone make anarchism possible. Let us secure the just, speedy, and impartial administration of law; let us elect legislators who seek honestly to conform human legislation to the divine laws of the social order, without fear or favour. The way to counteract hostility to law is to make laws which deserve to be respected.

(8) H. G. Wells, New Worlds for Old (1908)

That Anarchist world, I admit, is our dream; we do believe - well, I, at any rate, believe this present world, this planet, will some day bear a race beyond our most exalted and temerarious dreams, a race begotten of our wills and the substance of our bodies, a race, so I have said it, 'who will stand upon the earth as one stands upon a footstool, and laugh and reach out their hands amidst the stars,' but the way to that is through education and discipline and law. Socialism is the preparation for that higher Anarchism; painfully, laboriously we mean to destroy false ideas of property and self, eliminate unjust laws and poisonous and hateful suggestions and prejudices, create a system of social right-dealing and a tradition of right-feeling and action. Socialism is the schoolroom of true and noble Anarchism, wherein by training and

restraint we shall make free men.

(9) Alice Hamilton, Exploring the Dangerous Trades (1943)

Prince Peter Kropotkin was one of the most lovable persons I have ever met. He was a typical revolutionist of the early Russian type, an aristocrat who threw himself into the movement for emancipation of the masses out of a passionate love for his fellow man, and a longing for justice.

He stayed some time with us at Hull House, and we all came to love him, not only we who lived under the same roof but the crowds of Russian refugees who came to see him. No matter how down-and-out, how squalid even, a caller would be., Prince Kropotkin would give him a joyful welcome and kiss him on both cheeks.

It was most unfortunate that his visit to us came just a short time before the assassination of McKinley. That event woke up the dormant terror of anarchists which always lay close under the surface of Chicago's thinking and feeling, ever since the Haymarket riot. It was known that Czolgosz, the assassin, had been in Chicago at the time when both Emma Goldman and Kropotkin were there, and a rumor started that he had met them and the plot had been of their making - Czolgosz had been their tool. Then the story came to involve Hull House, which had been the scene of these secret, murderous meetings.

(10) Charles Fickert, during the trial of Tom Mooney (January 1917)

This defendant and his fellow-anarchists, in the time of peace, murdered ten men and women because these anarchists were bent on destroying the very government which Lincoln preserved and defended. The question which concerns you, gentlemen, here, as well as every other citizen of this great republic, is either to destroy anarchy or the anarchists will destroy the State.

If the moral fibre of the people of this nation has been so weakened; if the seeds of anarchy have been so implanted in the body politic that we refuse or neglect to defend our citizens at home or abroad; when helpless women and children can be ruthlessly slain on the streets of our city, and those who murder them go unpunished, because those who have been sworn to enforce the laws have tailed through neglect or fear to do their duty - we can then say farewell to the greatness of our nation; our boasted civilization is then only a self-delusion resting on the edge of a political abyss.

(11) Molly Steimer, speech made in court during her trial under the Espionage Act (October, 1918)

Anarchism is a new social order where no group shall be governed by another group of people. Individual freedom shall prevail in the full sense of the word. Private ownership shall be abolished. Every person shall have an equal opportunity to develop himself well, both mentally and physically. We shall not have to struggle for our daily existence as we do now. No one shall live on the product of others. Every person shall produce as much as he can, and enjoy as much as he needs - receive according to his need. Instead of striving to get money, we shall strive towards education, towards knowledge.

While at present the people of the world are divided into various groups, calling themselves nations, while one nation defies another - in most cases considers the others as competitive - we, the workers of the world, shall stretch out our hands towards each other with brotherly love. To the fulfillment of this idea I shall devote all my energy, and, if necessary, render my life for it.

(12) Cyril Connolly, New Statesman (21st November 1936)

It is in Barcelona that the full force of the anarchist revolution becomes apparent. Their initials, CNT and FAI, are everywhere. They have taken over all the hotels, restaurants, cafes, trains, taxis, and means of communication, as well as all theatres, cinemas, and places of amusement. Their first act was to abolish the tip as being incompatible with the dignity of those who receive it, and to attempt to give one is the only act, short of making the Fascist salute, that a foreigner can be disliked for.

Spanish anarchism is a doctrine which has gone through three stages. The first was the conception of pure anarchy which grew out of the writings of Rousseau, Proudhon, Godwin, and to a lesser extent, Diderot and Tolstoy. The essence of this anarchist faith is that there exists in mankind a natural trend towards nobility and dignity; human relations based on a love of liberty combined with a desire to help each other (as shown for instance in the mutual generosity of the poor in slum districts in cases of sickness and distress) should in themselves be enough, given education and the right economic conditions, to provide a working basis for people to live on; State interference, armies, property, would be as superfluous as they were to the early Christians. The anarchist paradise would be one in which the instincts towards freedom, justice, intelligence and "bondad" in the human race develop gradually to the exclusion of all thoughts of personal gain, envy, and malice. But there exist two stumbling blocks to this ideal - the desire to make money and the desire to acquire power. Everybody who makes money or acquires power, according to the anarchists, does so to the detriment of himself and at the expense of other people, and as long as these instincts are allowed free run there will always be war, tyranny, and exploitation. Power and money must therefore be abolished altogether. At this point the second stage of anarchism begins, that which arises from the thought of Bakunin, the contemporary of Marx. He added the rider that the only way to abolish power and money was by direct action on the bourgeoisie in whom these instincts were incurably ingrained, and who took advantage of all liberal legislation, all concessions from the workers, to get more power and more money for themselves. "The rich will do everything for the poor but get off their backs," Tolstoy has said. "Then they must be blown off," might have been Bakunin's corollary. From this time (the Eighties) dates militant anarchism with its crimes of violence and assassination. In most of its strongholds, Italy, Germany, Russia, it was either destroyed by Fascism or absorbed by Communism, which has usually seemed more practical, realisable, and adaptable to industrial countries; but in Spain the innate love of individual freedom, a personal dignity of the people, made them prefer it to Russian Communism, and the persecution which it underwent was never sufficient to blot it out.

Finally, in the last few years it has gone through a third transformation; in spite of its mystical appeal to the heart anarchism has always been an elastic and adaptable faith, and looking round for a suitable machinery to replace State centralisation it found syndicalism, to which it is now united. Syndicalism is a system of vertical rather than horizontal Trade Unions, by which, for instance, all the workers on this paper, editors, reviewers, printers and distributors, would delegate members to a syndicate which would negotiate with other syndicates for the housing, feeding, amusements, etc., of all the body. This anarcho-syndicalism through its organ, the CNT, has been able to get control of all the industries and agriculture of Catalonia and much of that in Andalusia, Valencia and Murcia, forming a more or less solid block from Malaga to the French frontier with considerable power also in the Asturias and Madrid. The executive militant spearhead of the body is the Federacion Anarquistica Iberica, usually pronounced as one word, FAI, which partly owing to acts of terrorism, partly to its former illegality, is clothed in mystery today. It is almost impossible to find out who and how many belong to it.

The ideal of the CNT and the FAI is libertarian Communism, a Spain in which the work and wealth is shared by all, about three hours' work a day being enough to entitle anyone to sufficient food, clothing, education, amusement, transport, and medical attention. It differs from Communism because there must be no centralisation, no bureaucracy, and no leaders; if somebody does not want to do something, the anarchists argue, no good will come of making them do it. They point to Stalin's dictatorship as an example of the evils inherent in Communism. The danger of anarchism, one might argue, is that it has become such a revolutionary weapon that it may never know what to do with the golden age when it has it, and may exhaust itself in a perpetual series of counter-revolutions. Yet it should be an ideal not unsympathetic to the English, who have always honoured freedom and individual eccentricity and whose liberalism and whiggery might well have turned to something very similar had they been harassed for centuries, like the Spanish proletariat, by absolute monarchs, militant clergy, army dictatorships and absentee landlords.