Johann Most

Johann Most, the illegitimate son of a clerk and governess, was born in Augsburg, Germany, in 1846. his mother died when he was a child and he was brought up by a stepmother who treated him badly. He also suffered from a disease that badly disfigured his face.

In 1867 he moved to Vienna where he joined the International Working Men's Association (the First International). A committed socialist he became a well-known street orator. Most was jailed three times for his political activities and in 1871 he was deported from Austria. Most returned to Germany where he worked as a journalist. In 1874 he was elected to the German Reichstag but after the passing of anti-socialist laws he was forced to flee the country.

In 1878 Most arrived in London where he converted to anarchism. The following year he began publishing Die Freiheit. When Most published an article in 1881 praising the assassination of Tsar Alexander II of Russia, he was arrested and sent to prison for 18 months.

When Most was released from prison in 1882 he emigrated to the United States and settled in Chicago. Most continued to publish Die Freiheit and soon became the best known anarchist in America. He argued that the state should be ruled by a collective group of citizens. He believed that before this could happen that people would have to use violence to overthrow the government. Most's notoriety grew with the publication of his book The Science of Revolutionary Warfare (1885).

The young Emma Goldman heard him lecture on anarchism in 1889: "My first impression of Most was one of revulsion. He was of medium height, with a large head crowned with greyish bushy hair: but his face was twisted out of form by an apparent dislocation of the left jaw. Only his eyes were soothing; they were blue and sympathetic." They soon began a close relationship: "Most took me to the Grand Central in a cab. On the way he moved close to me. Something mysterious stirred me. It was infinite tenderness for the great man-child at my side. As he sat there, he suggested a rugged tree bent by winds and storm, making one supreme last effort to stretch itself toward the sun. The fighter next to me had already given all for the cause. But who had given all for him? He was hungry for affection, for understanding. I would give him both."

Most and Goldman travelled the country making speeches on politics. They also co-authored the book Anarchy Defended by Anarchists (1896). However the two fell out over Most's criticism of her companion, Alexander Berkman, after he attempted to murder the industrialist, Henry Frick.

Johann Most continued to publish Die Freiheit and books and pamphlets on anarchism until his death in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1906.

Primary Sources

(1) Emma Goldman, Living My Life (1931)

My first impression of Most was one of revulsion. He was of medium height, with a large head crowned with greyish bushy hair: but his face was twisted out of form by an apparent dislocation of the left jaw. Only his eyes were soothing; they were blue and sympathetic.

Most took me to the Grand Central in a cab. On the way he moved close to me. Something mysterious stirred me. It was infinite tenderness for the great man-child at my side. As he sat there, he suggested a rugged tree bent by winds and storm, making one supreme last effort to stretch itself toward the sun. The fighter next to me had already given all for the cause. But who had given all for him? He was hungry for affection, for understanding. I would give him both.

(2) Emma Goldman, Living My Life (1931)

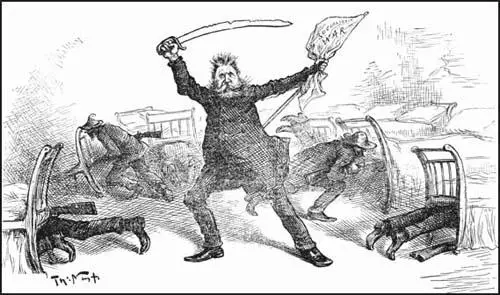

Hardly a week passed without some slur in Die Freiheit against Sasha (Alexander Berkman) or myself. It was painful enough to be called vile names by the man who had once loved me, but it was beyond endurance to have Sasha slandered and maligned. Most, whom I had heard scores of times call for acts of violence, who had gone to prison in England for his glorification of tyrannicide. Most, the incarnation of defiance and revolt, now deliberately repudiated the deed.

At Most's next lecture I sat in the front row, close to the platform. My hand was on the whip under my long grey cloak. When he got up and faced the audience, I rose and declared in a a loud voice: "I've come to demand proof of your insinuations against Alexander Berkman. There was instant silence, then Most mumbled something about "hysterical woman," but nothing else. I then pulled out my whip and leaped towards him. Repeatedly I lashed him across the face and neck, then broke the whip over my knee and three the pieces at him. It was done so quickly that no one had time to interfere.