Bill Shankly

William (Bill) Shankly, the son of John and Barbara Shankly, was born at the mining village of Glenbuck in Scotland on 2nd September, 1913. Bill had four brothers (John, Bob, Jimmy and Alec) and five sisters (Netta, Elizabeth, Isobel, Barbara and Jean).

Although most of the men living in the village worked as miners, John Shankly was a tailor. People living in Glenbuck were strong trade unionists and during his youth Bill Shankly developed socialist beliefs. "The socialism I believe in is not really politics. It is a way of living. It is humanity. I believe the only way to live and to be truly successful is by collective effort, with everyone working for each other, everyone helping each other, and everyone having a share of the rewards at the end of the day."

Bill Shankly's mother was very interested in football. Her two brothers, Robert Blyth and and William Blyth, both moved to England to play professional football. Both became involved in the administration of football with Robert being appointed chairman of Portsmouth and William was director of Carlisle United for many years.

Bill Shankly attended the local village school: "We played football in the playground, of course, and sometimes we got a game with another school, but we never had an organized school team. It was too small a school. If we played another school we managed to get some kind of strip together, but we played in our shoes."

Bill Shankly - Glenbuck Colliery

Bill Shankly left school at 14 and like the other boys in the village went to work at the Glenbuck Colliery. As he later recalled: "My wages would be no more than two shillings and sixpence a day. My job was to empty the trucks when they came up full of coal and send them back down the pit again and to sort out the stones from the coal on a conveyer-belt... After about six months working at the pit top, a job that was active but not heavy, I went down to the pit bottom. The coal mines and pits were the first places to have electricity, before people had it in their houses, and the pit was like Piccadilly Circus. First I would shift full trucks and put them into the cages and then take out the empty trucks and run them along to where they were loaded."

Shankly played junior football for for Cronberry Eglinton. In 1932 a scout working for Carlisle United, saw Shankly play and arranged for him to join the club. Like his four brothers, John Shankly, Bob Shankly, Jimmy Shankly and Alec Shankly, Bill was now a professional footballer. As he later pointed out in his autobiography, Shankly: "All the boys became professional footballers and once, when we were all at our peaks, we could have beaten any five brothers in the world." In fact, despite only having a population of less than a 1,000 people, the village produced near fifty professional footballers in a sixty year period.

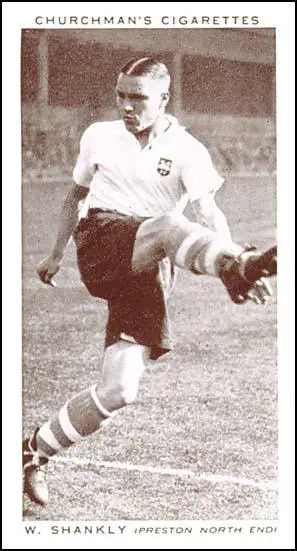

Preston North End

Bill Shankly was transferred to Preston North End for £500 in 1933. A teetotaler, non-smoker and fitness fanatic, this very energetic 20 year old, formed a great partnership with former English international, Robert Kelly. In the 1933-34 season Kelly and Shankly helped the club win promotion to the First Division.

Kelly, now aged 41, was considered too old for First Division football and was allowed to become player manager at Carlisle United. Preston signed another veteran, Ted Critchley, to replace Kelly. Other players brought in that year included Jimmy Maxwell (Kilmarnock) and Jimmy Dougal (Falkirk). In the 1934-35 season Preston finished 11th in the league. Maxwell, who played at centre-forward, was the club's leading scorer with 26 league and cup goals.

The following season Preston North End persuaded the Scottish international, Tom Smith, to join the club. Other signings that year included the brothers, Hugh O'Donnell and Francis O'Donnell, from Celtic.

In the 1935-36 season, Preston finished 7th in the league. Jimmy Maxwell was again top scorer with 19 goals in all competitions. Shankly, a powerful wing half, had emerged as the most important player in the team. He rarely missed a game and helped Preston North End reach the 1937 FA Cup Final against Sunderland at Wembley. Francis O'Donnell scored in the first-half but with Raich Carter in top form, Sunderland responded by scoring three in reply.

At the beginning of the next season, Preston made two important signings. In September, 1937, Preston purchased the high scoring George Mutch, from Manchester United for £5,000. The following month, Robert Beattie a skillful inside forward, arrived from Kilmarnock for a fee of £2,500. They joined fellow Scotsmen, Bill Shankly, Jimmy Dougal, Andrew Beattie, Jimmy Maxwell, Tom Smith, Hugh O'Donnell, Francis O'Donnell and Andrew McLaren.

In the 1937-38 season Preston North End (49 points) finished 3rd in the First Division of the Football League behind Arsenal (52) and Wolverhampton Wanderers (51). Preston also had another successful run in the 1937-38 FA Cup. Preston beat West Ham United in the 3rd round with George Mutch scored a hat trick. Mutch also scored goals in the 4th round against Leicester City and in the semi-final when Preston beat Aston Villa 2-1.

In the FA Cup Final Preston played Huddersfield Town. This was the first time that a whole match was shown live on television. Even so, far more people watched the game in the stadium as only around 10,000 people at the time owned television sets. No goals were scored during the first 90 minutes and so extra-time was played. In the last minute of extra-time, Bill Shankly put George Mutch through on goal. Alf Young, Huddersfield's centre-half, brought him down from behind and the referee had no hesitation in pointing to the penalty spot. Mutch was injured in the tackle but after receiving treatment he got up and scored via the crossbar. It was the only goal in the game and Shankly won a cup winners' medal.

Scottish International

Shankly had a magnificent season and on 9th April, 1938 he won his first international cap when he played for Scotland against England at Wembley. Also in the Scottish team were Preston colleagues, George Mutch, Andrew Beattie, Tom Smith and Francis O'Donnell. Scotland won 1-0 with Mutch scoring the only goal of the game. Later that season, two other Preston players, Jimmy Dougal and Robert Beattie, were called up to play for Scotland.

Shankly also played for Scotland against Northern Ireland (October, 1938), Wales (November, 1938), Hungary (December, 1938) and England (April, 1939). Shankly's international career was interrupted by the outbreak of the Second World War. Games in the Football League were brought to an end as the government imposed a fifty mile travelling limit. However, the clubs were divided into seven regional areas where games could take place. In the 1940-1941 season Preston North End needed to win their last game against Liverpool to win the North Regional League title. The nineteen year old Andrew McLaren scored all six goals in the 6-1 victory.

Preston North End also took part in the 1941 Football League War Cup. The teenage Andrew McLaren scored five of the goals in Preston's 12-1 victory over Tranmere. He also scored a hat-trick in the fourth-round tie against Manchester City. Preston reached the final by beating Newcastle United 2-0. The Preston team that faced Arsenal at Wembley on 31st May was: Jack Fairbrother, Frank Gallimore, William Scott, Bill Shankly, Tom Smith, Andrew Beattie, Tom Finney, Andrew McLaren, Jimmy Dougal, Robert Beattie and Hugh O'Donnell.

The game took place in front of a 60,000 crowd. Arsenal was awarded a penalty after only three minutes but Leslie Compton hit the foot of the post with the spot kick. Soon afterwards Andrew McLaren scored from a pass from Tom Finney. Preston dominated the rest of the match but Dennis Compton managed to get the equaliser just before the end of full-time.

The replay took place at Ewood Park, the ground of Blackburn Rovers. The first goal was as a result of a move that included Tom Finney and Jimmy Dougal before Robert Beattie put the ball in the net. Frank Gallimore put through his own goal but from the next attack, Beattie scored again. It was the final goal of the game and Preston ended up the winners of the cup.

Bill Shankly retired from playing football in 1948. During his time at Preston North End he scored 14 goals in 337 league and cup games. This included a record 43 successive FA Cup ties.

Shankly became the coach of Preston's reserve team but in March, 1949 he agreed to become manager of Carlisle United. The club finished 3rd in the Third Division (North) league in 1950-51. Carlisle had little money to spend and in 1951 he resigned complaining about a lack of resources. It was a similar story at Grimsby Town (1951-54) and Workington (1954-55).

In 1956 Shankly became assistant manager under Andrew Beattie at Huddersfield Town, a club that had just been relegated from the First Division of the Football League. Soon after joining the club, Shankly signed the 15 year old Dennis Law. Over the next three years Shankly was involved in keeping Law at the club. This included an offer of £45,000 from Everton.

Bill Shankly - Liverpool

Shankly did not manage to get Huddersfield Town back into the First Division finishing 12th (1956-57), 9th (1957-58) and 14th (1958-59). In December 1959, Shankly became manager of Liverpool, another Second Division club trying to get promotion to the top league. Shankly got them into 3rd place in 1959-60. He repeated this in 1960-61, but the following year won the championship with 62 points.

George Scott, Alfie Arrowsmith, Ron Yeats, Tommy Lawrence, Jim Furnell,

Fred Molyneaux, Alex Totten, Alan A'Court and Brian Halliday.

Wilf Mannion was a great advocate of Shankly's man-management: "What I like about Bill is that he never panics. Even when things weren't going so well, he stuck to the same team and gave them a chance to settle down. 'Panic and all is lost,' is one of the Shankly maxims. Everything Bill does is done to plan. Even training is scheduled to a strict timetable. But that doesn't make him a strict disciplinarian. Far from it. He is one of the easiest-going characters I have met. Ask the players. He's always 'Bill' to them. There's no 'Mr' or 'Boss' when he's around. 'Let the players regard you as an equal,' says Bill, 'and you gain just as much respect.' I couldn't agree more."

Liverpool finished in a respectable 8th place in their first season back in the First Division. The following season (1963-64) they won the league with their arch-rivals, Everton, finishing in 3rd place. Over the next ten years Liverpool won the league on two more occasions: 1965-66 and 1972-73. They also won the FA Cup in 1974.

Shankly remained interested in politics and once said: "The socialism I believe in is everybody working for the same goal and everybody having a share in the rewards. That's how I see football, that's how I see life."

In July, 1974, Shankly, now 60 years old, decided to retire. He later commented: "It was the most difficult thing in the world, when I went to tell the chairman. It was like walking to the electric chair." He was replaced by Bob Paisley. Soon after he retired Shankly was awarded the OBE.

Bill Shankly died of a heart attack on 28th September, 1981.

Primary Sources

(1) Bill Shankly, Shankly (1977)

I was born in a little coal-mining village called Glenbuck, about a mile from the Ayrshire-Lanarkshire border, where the Ayrshire road was white and the Lanarkshire road was red shingle. We were not far from the racecourses at Ayr, Lanark, Hamilton Park and Bogside.

Ours was like many other mining villages in Scotland in 1913. By the time I was born the population had decreased to seven hundred, perhaps less. People would move to other villages, four or five miles away, where the mines were possibly better...

There was the village council school and a higher-grade school in the village of Muirkirk three miles away. I just went to the village school. We played football in the playground, of course, and sometimes we got a game with another school, but we never had an organized school team. It was too small a school. If we played another school we managed to get some kind of strip together, but we played in our shoes.

(2) Bill Shankly, Shankly (1977)

When I left school I went to work at the pit, which was the usual thing in the village. I worked a section with my brother Bob for a time. Occasionally a boy would take a job on a farm, but we were not farm-minded people really.

There were plenty of mines, into which you could walk down an incline, and plenty of pits, where you had to go down by cage. There was no unemployment in the village at that time.

I went to a pit and spent the first six months working at the pit top. My wages would be no more than two shillings and sixpence a day. My job was to empty the trucks when they came up full of coal and send them back down the pit again and to sort out the stones from the coal on a conveyer-belt.

On Sunday you could make extra money emptying wagons of the fine coal we called dross, which was fed into about six big Lancashire boilers. You got sixpence a ton and each wagon contained maybe eight to ten tons. I've been in on a Sunday, just me and my shovel - as big as the wagon - and emptied two wagons, twenty tons, on my own. It was light stuff and nothing to us.

After about six months working at the pit top, a job that was active but not heavy, I went down to the pit bottom. The coal mines and pits were the first places to have electricity, before people had it in their houses, and the pit was like Piccadilly Circus. First I would shift full trucks and put them into the cages and then take out the empty trucks and run them along to where they were loaded. I did more running than lifting and at the end of an eight-hour shift I had probably run ten or twelve miles. This might have done me good - marathon-running!

Then I went into the back of the pit itself, where they were digging the coals and where they had the stables in which the ponies were kept. I felt sorry for the animals. When they were lowered down to the bottom of the pit, below the cage, it looked like cruelty, but it wasn't really. I've seen them in their stables, eating their straw. They could be there for months at a time. Then they took a break. They were blind then, but they recovered their sight. They used to pull a dozen of the trucks on the rails from the back end of the pit to the pit bottom.

At the back of the pit you realized what it was all about: the smell of damp, fungus all over the place, seams that had been worked out and had left big gaps, and the stench - not the best of air, though possibly better ventilated in mines and pits now. There was a ventilation system which diverted the air through channels with doors, canvas and all kinds of things. You were supposed to get air but I'm sure there were some places it did not reach. People got silicosis because they had no decent air to breathe.

In one part of the pit you went up an incline with the water gushing down it, and if the trucks went off the rails there, what an operation it was to put them back on again!

You would be down there eight hours and you would have your grub to eat there and a tea can wrapped up in a big, thick newspaper to keep it warm for a couple of hours, perhaps even less. You had to drink your tea maybe an hour after you'd started, otherwise it would probably be cold. You had to eat where you were working and there was no place to wash your hands. It was really primitive. The longest break you would get for anything would be half an hour, but if a man was digging coal on piece-work he could stop to eat anytime. If there were six men doing a job, three would take a break while three worked.

We would see a lot of rats in a mine, though not as many in a pit. In a mine the rats could go down the incline. But they did not frighten the men. Not at all. I have seen rats sitting on men's laps eating.

I went to the coal-face, but I didn't actually dig any coal. I was too young. I saw the firing of shots to bring down the coal - men boring the big holes, stabbing them up with powder or gelignite and then... whoof!

And men putting up props before they could go in and waiting for the smoke to clear. A lot of men went in before the smoke had cleared, and they would get severe headaches.

We were filthy most of the time and never really clean. It was unbelievable how we survived. You could not clean all the parts of your body properly. Going home to wash in a tub was the biggest thing. The first time I was in a bath was when I was fifteen...

After about two years in the pit I was unemployed. The old, old story. The pits closed. All of them. Men had to travel to other villages where the mines and pits were still working. I remember two men, James and Will McLatchie, who walked seven miles to a place appropriately called Coalburn, did a shift, and walked seven miles back. The pits started at seven o'clock in the morning, so if you were not at the pit-head then, when they started winding up coal, you didn't get down.

(3) David P. Worthington, Bill Shankly: The Glenbuck Years (1997)

It was said that any Scottish town or village that didn’t have a decent football team had got its civic priorities wrong. Glenbuck was certainly no exception to this rule, the club had its beginnings in the late 1870`s and was founded by Edward Bone, William Brown and others. It was originally called Glenbuck Athletic and wore club colours of white shirts and black shorts. The Glenbuck team had two earlier grounds before finally settling at Burnside Park. It was at the turn of the century that the team changed its name to that of Glenbuck Cherrypickers. Initially a nickname, Cherrypickers was soon adopted as the clubs official name, something that continued to the end. Over the years The Cherrypickers won numerous local cups including the Ayrshire Junior Challenge Cup, the Cumnock Cup, and the Mauchline Cup. Despite all their honours the real place of Glenbuck in footballing history was as a nursery of footballers. It is thought that Glenbuck had provided around fifty players who plied their trade in senior football at least half-a-dozen who played for Scotland - not bad for a village whose population never exceeded twelve hundred.

(4) Stephen F. Kelly, Bill Shankly (1997)

In 1933, Preston North End were a club with a rich history but a gloomy-looking future... When Bill Shankly landed on their doorstep, they were little more than a moderate Second Division side. They had been relegated in 1925 along with Nottingham Forest and had struggled ever since to escape the anonymity of Second Division soccer. In the season before Shankly arrived, they had finished ninth in the table, fourteen points adrift of champions Stoke City.

Like so many other industrial cities, Preston suffered appallingly during the thirties. The Depression hit Lancashire hard. Across the country, the number of unemployed rose to 2.9 million, a staggering 20% of the working population and, if those who were unregistered were included, the total was nearer three-and-a-half million. Everywhere, the unemployed protested.

In Lancashire, they marched to Preston and in Scotland they descended on Glasgow, while those from Jarrow in the North-east marched bravely to London, pricking the conscience of the nation. The politicians called the unemployed regions Distressed Areas. It somehow sounded better. Unemployment benefit was basic if not downright miserable. The Means Test, with its crippling rules, ensured that money was only forthcoming if certain stringent criteria were met. And, when money was paid out, it was done so begrudgingly and in small amounts. Few claimants met the criteria; most survived thanks only to family and friends.

In some areas of Lancashire, unemployment topped the 25% mark. Preston was a cotton-spinning town and like all the cotton towns of Lancashire had been severely shaken by the Depression. Almost half a million cotton workers were on the dole. Exports to India had crashed. Looms lay idle; mills were closing. Unemployment in Preston, even though it hit an all-time high, may not have been as bad as some parts of Lancashire, like Mersyside and Blackburn, but there were still more than 15% on the dole...

Shankly was as aware as anyone of the problems of unemployment: he'd seen it all before. In Ayrshire, his family and friends had suffered as the mines closed and it was little better in Carlisle. He'd spent a couple of months on the dole himself and was well aware of the humiliations that unemployment brought. But in case he had forgotten, he was to be rudely awoken by what he saw in Preston.

Shankly was lucky. At the end of his first season, his wages had risen to £8 with £6 in summer, a small fortune in a place like Preston. It allowed for the luxury of going out occasionally though, as ever, much of his money was sent home to his family in Ayrshire. But it would get better. Shankly arrived at the peak of unemployment and, as the thirties unwound, jobs were beginning to return and with them wealth creation. Even the fortunes of Preston North End began to look up...

It was a learning process and Shankly was developing as rapidly as anyone. By December, he had made the first team. He made his debut against newly promoted Hull City on Saturday 9 December. Ironically, Shankly had played against Hull just a few months earlier when he was with Carlisle and had been on the wrong end of a 6-1 drubbing. This time, the boot was on the other foot. Preston won 5-0. Preston were three goals up within half an hour with Shankly having a hand in the second goal. His arrival did not go unnoticed in the press. 'Shankly passed the ball cleverly,' reported the Sporting Chronicle without going into further detail. It was probably the first time his name had appeared in a national paper.

By the end of the season, Preston had clinched promotion as runners-up to champions Grimsby. It was to be the start of a famous period in Preston's history. They had begun the season confidently and after a couple of games were topping the table. By October however, they had slipped and by early December they were down to seventh place. But then the inclusion of Shankly seemed to revive them. Their win over Hull hoisted them into sixth spot, some way behind Grimsby who were runaway leaders almost the entire season.

Preston were not always obvious promotion candidates. One week, they would shoot up the table and, overtake their promotion rivals, only to lose their next game and slither back the following one. Grimsby had clinched promotion by early April, but the second promotion place remained in doubt until the final day of the season.

It was neck and neck between Bolton Wanderers and Preston, two of Lancashire's most famous clubs. Both teams had 50 points from 41 games: Bolton looked to have the easier final fixture with a visit to Lincoln, while Preston were at Southampton. But much to everyone's surprise, Bolton could manage only a draw while Preston won 1-0 and were into the First Division. After making his debut in December, Shankly had gone on to play all season. Once he was in the side, he was there to stay and undoubtedly became an important influence on Preston's promotion challenge.

(5) Bill Shankly, Shankly (1977)

I was a hard player, but I played the ball, and if you play the ball you'll win the ball and you'll have the man too. But if you play the man, that's wrong. Wilf Copping played for England that day, and he was a well-known hard man. The grass was short, the ground was quick, and I was playing the ball. The next thing I knew, Copping had done me down the front of my right leg. He had burst my stocking - the shin-pad was out - and cut my leg. That was after about ten minutes, and it was my first impression of Copping. He was at left half and we came into contact in the middle of the field. I think the pitch was more responsible for what happened than anything, but I was surprised that he would do what he did to me in an international match. He was older than me and had a reputation. He didn't need to be playing at home to kick you -he would have kicked you in your own backyard or in your own chair. He had no fear at all. But while we were fighting for Scotland that day, we didn't go round trying to cripple people.

What Copping did stung me, but I didn't complain about him. I said to him, "Oh, you're making the game a little more important." Frank O'Donnell, who could look after himself, was annoyed at Copping and told him what he thought about it.

Copping had been after me and had caught me and I never contacted him again during the match. But he also hurt me when I played against him for Preston at Highbury on a Christmas Day. One of our players pulled out of a tackle for the ball and I had to go in to fight for it, and Copping caught me on my right ankle.

I was due to play another match the following day, but my ankle had blown up to an awful size. We went from London up to Fleetwood and Bill Scott said, "We'll have a try-out in the morning."

"What do you mean, a try-out?" I asked him, and I soon found out. Next morning my ankle was still badly swollen, and Bill got me a bigger boot to wear on my right foot. My normal size was six and a half, but I put on a size seven and a half or eight that day.

For years afterwards I played with my ankle bandaged and wore a gaiter over my right boot for extra support, and to this day my right ankle is bigger than my left because of what Copping did. My one regret is that he retired from the game before I had a chance to get my own back.

(6) Barney Ronay, The Guardian (25th April, 2007)

Bill Shankly is probably still British football's most celebrated socialist. Wisecracking, dapper and a charismatic orator, Shankly was a hugely successful manager of Liverpool through the 60s and early 70s. What seems most remarkable about him now is his insistence on talking politics, even while talking football: "The socialism I believe in is everyone working for each other, everyone having a share of the rewards. It's the way I see football, the way I see life."

Shankly traced his political beliefs to his upbringing in the Ayrshire mining village of Glenbuck. A childhood spent in areas dominated by heavy industry and trade union influence has been a common theme among football's senior socialists. Sir Alex Ferguson was a Govan shipyard shop steward before he became a player with Rangers. His backing for the Blair Labour leadership is well documented. At the last general election he posted a message on the government's website praising "two brilliant barnstorming speeches from Tony and Gordon". Ferguson, with his fine wines and his multi-million pound racehorse ownership disputes, has frequently been subjected to the familiar jibe of "champagne socialism". Football is fond of this kind of reasoning, based on the idea that those with socialist beliefs are expected to live exemplary altruistic lives, whereas rightwingers can pretty much do whatever they want. Nottingham Forest legend Brian Clough, a sponsor of the anti-Nazi League and a regular on picket lines during the miners' strike, had his own riposte. "For me, socialism comes from the heart. I don't see why certain sections of the community should have the franchise on champagne and big houses."

(7) Dean Hayes, Who's Who of Preston North End (2006)

At Deepdale his skills were honed to perfection among a growing contingent of Scotsmen. Always fiercely enthusiastic, Shankly's brash, competitive nature made him a key figure in helping his new club to promotion from Division Two at the end of his first season. A teetotaller, non-smoker and fitness fanatic, he was instrumental in helping North End reach two successive FA Cup finals, picking up a winners' medal in 1938. In his first eight seasons at Deepdale, Shankly missed only 28 out of a maximum 319 games and stood down only once through injury.

(8) Tom Finney, My Autobiography (2003)

It might have been watered-down fare, but regional wartime football was fine by me. I very much doubt that in normal circumstances I would have started the first game of the 1940-41 season playing for the Preston first team against Liverpool at Anfield.

Also in our team that day was a man who, many years later, was to become a Liverpool legend - the Liverpool legend - the great Bill Shankly. If my father was my guiding light in life, Bill Shankly was my football mentor. Has there been anyone with a greater love for the game? If there has, I have yet to meet him.

Shanks was unique, a complete one-off: He caused a great stir when he described football as more important than life or death and, what is more, he meant it. He was the best pal in the world to anyone prepared to eat, sleep and drink football, but a man with no time for those who failed to meet his standards. Extremely fit, his enthusiasm was infectious and the word defeat didn't have a place in his vocabulary. Bill influenced so many and so much, and his contribution to the game cannot be exaggerated - unlike many of the tales about him and his antics.

Shanks first set foot in Deepdale in 1933 and within months, at just 19, he was in the first team. As you may imagine, he wasn't a guy to give up his shirt without a fight and he followed his debut by playing 85 games in a row. He stayed for 17 seasons, eventually returning to Carlisle as manager. During his time at Preston, he won an FA Cup winner's medal, in 1938, and was capped by Scotland; he was also a member of our double-winning wartime side.

He was an established player when I first encountered him during my days as a junior. He invariably popped along to our matches - Bill would stop off anywhere a game of football was being played and, even at that early stage of his career, you knew he would go into coaching and management and make a damn good job of it.

A much better all-round player than some might have you believe, Shanks worked tirelessly to improve. After morning training he was always asking if anyone fancied going back for an extra session or a game of head tennis in the afternoon.

(9) Bill Shankly, Quotations, Education Forum (April, 2007)

1. "Some people believe football is a matter of life and death, I am very disappointed with that attitude. I can assure you it is much, much more important than that."

2. "If Everton were playing at the bottom of the garden, I'd pull the curtains."

3. "The trouble with referees is that they know the rules, but they don't know the game."

4. "A lot of football success is in the mind. You must believe that you are the best and then make sure that you are. In my time at Liverpool we always said we had the best two teams in Merseyside, Liverpool and Liverpool reserves."

5. "Liverpool was made for me and I was made for Liverpool."

6. "Of course I didn't take my wife to see Rochdale as an anniversary present, it was her birthday. Would I have got married in the football season? Anyway, it was Rochdale reserves."

7. "If you are first you are first. If you are second you are nothing."

8. "With him in defence, we could play Arthur Askey in goal." (Bill Shankly talking about Ron Yeats.)

9. "The difference between Everton and the Queen Mary is that Everton carry more passengers!"

10. "At a football club, there's a holy trinity - the players, the manager and the supporters. Directors don't come into it. They are only there to sign the cheques". (Bill Shankly on boardroom meetings.)

11. "I'm just one of the people who stands on the kop. They think the same as I do, and I think the same as they do. It's a kind of marriage of people who like each other."

12 "It was the most difficult thing in the world, when I went to tell the chairman. It was like walking to the electric chair. That's the way it felt." (Bill Shankly on the leaving of Liverpool.)

13. "If you can't make decisions in life, you're a bloody menace. You'd be better becoming an MP!"

14. "My idea was to build Liverpool into a bastion of invincibility. Napoleon had that idea. He wanted to conquer the bloody world. I wanted Liverpool to be untouchable. My idea was to build Liverpool up and up until eventually everyone would have to submit and give in."

15. "I don't think I was in a bath until I was 15 years old. I used to use a tub to wash myself. But out of poverty with a lot of people living in the same house, you get humour."

16. "It's there to remind our lads who they're playing for, and to remind the opposition who they're playing against."

17. "I know this is a sad occasion but I think that Dixie would be amazed to know that even in death he could draw a bigger crowd than Everton can on a Saturday afternoon." (Comment made at Dixie Dean's funeral.)

18. "The problem with you, son, is that all your brains are in your head." (Comment made to a Liverpool trainee.)

19. "I was the best manager in Britain because I was never devious or cheated anyone. I'd break my wife's legs if I played against her, but I'd never cheat her."

20. "No one was asked to do more than anyone else... we were a team. We shared the ball, we shared the game, we shared the worries."

21. "Football is a simple game based on the giving and taking of passes, of controlling the ball and of making yourself available to receive a pass. It is terribly simple."

22. During one match, Tommy Lawrence, the Liverpool goalkeeper, let the ball go through his legs. "Sorry, boss, I should have kept my legs together," said Lawrence. "No, Tommy, your mother should have kept her legs together!," replied Shankly.

23. "Son, you'll do well here as long as you remember two things. Don't over-eat and don't lose your accent." (Comment made to Ian St John on the day he signed him.)

24. "He's worse than the rain in Manchester. At least God stops the rain in Manchester occasionally." (Comment made on Brian Clough.)

25. "I've been a slave to football. It follows you home, it follows you everywhere, and eats into your family life. But every working man misses out on some things because of his job."

26. "A football team is like a piano. You need eight men to carry it and three who can play the damn thing."

27. "The socialism I believe in is everybody working for the same goal and everybody having a share in the rewards. That's how I see football, that's how I see life."

(10) Barney Ronay, The Guardian (16th August, 2007)

Liverpool manager Bill Shankly was the first to make an impression as a "personality" outside of the narrow confines of football. Shankly's success in the 60s and early 70s was soundtracked by his own apparently endless repertoire of quips and wisecracks, as the hitherto rather stilted and secretive world of football management acquired a public voice for the first time. A dapper, sharp-suited Scot, Shankly took his inspiration from American entertainers. His delivery was a cross between James Cagney and Groucho Marx, and he borrowed his defining epigram - the one about football not being a matter of life and death, but actually something much more important than that - from the gridiron coach, Vince Lombardi.

(11) Hugh McIlvanney is a football journalist from Scotland. He was interviewed by Rick Glanvill for his book Sir Matt Busby: A Tribute.

It was utterly extraordinary that three great managers, Matt Busby, Jock Stein and Bill Shankly, came from the same area of Scotland, and it was, I think, very significant. These people absorbed the best of the true ethos of that working-class environment. There was a richness of spirit bred into people from mining areas.

I'm likely to see it that way because my father worked in the pits for a while, but there is no question that there was a camaraderie. Stein said that he would never work with better men than he It was utterly extraordinary that three great managers, Matt Busby, Jock Stein and Bill Shankly, came from the same area of Scotland, and it was, I think, very significant. These people absorbed the best of the true ethos of that working-class environment. There was a richness of spirit bred into people from mining areas. I'm likely to see it that way because my father worked in the pits for a while, but there is no question that there was a camaraderie. Stein said that he would never work with better men than he did when he was a miner, that the guys who got carried away with football were never going to impress him much, and although Shankly was completely potty about the game and was the great warrior/poet of football, he nevertheless retained that sense of what real men should do, the sense of dignity, the sense of pride.

(12) Martin Kelner, The Guardian (12th January, 2009)

I love football stories from the old days but normally you have to eat a seafood starter, chicken breast with duchesse potatoes and garden peas, and watch some comedian do his Geoffrey Boycott impression to enjoy them. Now, though, Sky Sports has had the smart idea of bringing the best of the after-dinner circuit into the comfort of our own living rooms in Time Of Our Lives, a six-part nostalgia-fest featuring legends of the game.

The term legend, of course, is a fairly flexible one in sports broadcasting, but The Shankly Years, the first in the series, boasted a font of great anecdotes about the eponymous genuine article.

Ian St John, Chris Lawler and Ron Yeats, who between them played 1,200 games for Bill Shankly's Liverpool in the 1960s and early 1970s, gathered in a studio under the tutelage of Jeff Stelling to share memories of the great man (Shanks, that is, not Stelling), only occasionally straying into Monty Python Four Yorkshiremen territory, mainly on the topic of the former Liverpool boss's cavalier attitude to health and safety.

Yeats told the story of the defender Gerry Byrne, who had to be careful not to take throw-ins after he appeared in the second half of a cup final with a broken collarbone (you tell the youngsters that these days, they'll crash their Ferraris), and all three guests agreed that Shankly's attitude to injuries was what you might call a touch old-school.

He feared any player carrying an injury might infect the others, so his solution was to banish him to the far corner of the training field adjacent, apparently, to a pigsty. If Shanks saw a player on the treatment table — even one of his trusted lieutenants — he would shun him.

This might explain why Lawler missed only three games in seven seasons. When Shankly once saw Lawler wearing a crepe bandage on the advice of a physiotherapist, the manager barked: "What's wrong with the malingerer?" The full-back was pretty sure he was not joking.

There was little more to the programme than the three former players sitting in armchairs telling their stories — no archive footage, no expert views and only a brief clip of Shankly himself — and yet the hour flew by for those of us not overly familiar with the material. If the current Liverpool manager, Rafael Benítez, may appear mildly paranoid of late, he has nothing on his illustrious predecessor, who believed all foreigners were "cheats and liars" according to St John.

When Liverpool played at Internazionale in the semi-final of the 1965 European Cup, said St John, they stayed by Lake Como. Shankly was so convinced the bells at the little church up the hill were being deliberately rung to keep his players awake that he walked to the church with his assistant Bob Paisley, and asked if the ringing could be stopped.

When the Monsignor told him they had rung like that for centuries, Shankly asked if Paisley could muffle them. "He wanted Bob to climb up into the tower and bandage the bells," chuckled St John. Shankly was also deeply suspicious of coaching manuals, said St John — "He said if you need to read a book to know about football, you shouldn't be in the game" — and yet, according to the former Liverpool forward, he introduced the flat back four to British football.

To say Shankly was singleminded is rather like saying Oscar Wilde was a little flamboyant. He would turn up at the training ground for five-a-side games (Shankly, that is, not Oscar Wilde) even after his retirement in 1974, when Paisley took over. Eventually he had to be asked to stay away to avoid confusing the players as to who was the boss.

(13) George Scott, Bill Shankly (August, 2010)In January 1960 at the age of 15 I travelled to Liverpool from Aberdeen to sign for Bill Shankly as one of his first young players.

I remember getting off of the train at Lime Street Station and being met by Joe Fagan who was then the youth team coach. We got in a taxi and drove up the famous Scotland Road where Joe told me there was a pub on every corner and not to visit any of them ever.

We soon arrived at 258 Anfield Road where I was to share lodgings with two other apprentices, Bobby Graham and Gordon Wallace, both of whom later went on to play in the first team.

My first wage as an apprentice professional was £7.50 per week of which I gave £3.50 to my landlady for my lodgings and sent £2.00 per week home to my Mum in an envelope to help the family out. I was left with £1.50 per week which was enough in those days for a young man to have a great time for a week in Liverpool, including being able to watch the Beatles start their career playing live in the Cavern in Mathew Street.

In May 1961 outside the secretary’s office I found a complete record of the week’s wages to be paid in to Barclays Bank in Walton Vale for every player and member of staff at Anfield. Unbelievably the total wage bill for every player and all of the coaching and managerial staff in the Liverpool Football Club was five hundred and thirteen pounds, thirteen shillings, and two pence old money.

As Apprentice professionals, after cleaning the first team’s boots, painting the stands and clearing the rubbish from the Kop we used to play 5-a-sides in the car park behind the main stand every Monday morning. The opposition in these games was usually Bill Shankly, Bob Paisley, Joe Fagan, Ronnie Moran and Reuben Bennett. Our side was Bobby Graham, Gordon Wallace, Tommy Smith, Chris Lawler, and me. We never ever won those games because Shanks and company would have played until dark to make sure they got the result.

It was from one of these games that the famous true story has been passed down to generations of Liverpool fans.

We were playing the usual hard fought match and Chris Lawler was injured and watching from the sidelines. As we only had four men to their five, Shankly tried a long range effort to the unguarded goal which went over the shoe that we had layed down as a goalpost. He immediately shouted “Goal we have won, time up, get showered boys”.

Led by Tommy Smith we all hotly disputed the goal. Shankly saw that Chris Lawler was watching from the sidelines and shouted to him. ”You are in the perfect position son was that a goal?” Chris was a very quiet boy of few words and replied with one word “No” Shankly shouted at him in all seriousness” Son we have waited a year for you to speak and your first word is a lie”.

One of my first memories of Bill Shankly was in January 1960 when we were standing in the centre circle on the pitch while he was showing my father and me around a rather dilapidated Anfield. Liverpool at the time was in the second division and he had just taken over as Manager. He said that I should look around and be grateful that I had signed for the club at this time because this place was going to become a “Bastion of Invincibility and the most famous football club in the world”

My father worked at the time as a gardener for the Aberdeen City Council and during the conversation Bill asked him the question “Who are you with Mr Scott”? My Dad replied “I work for the City Mr Shankly” whereupon Bill responded by saying in his best James Cagney voice “What league do they play in?

After a two year apprenticeship, I signed full time professional forms on my 17th birthday on October 25th 1961. I made my reserve team debut along with Tommy Smith, Chris Lawler, Bobby Graham and Gordon Wallace as part of a very young Liverpool reserve team in the semi-final of the Lancashire Senior Cup against Manchester United reserves at Old Trafford in 1962 playing against some great old united players such as Albert Quixall, David Herd, Jimmy Nicholson, David Gaskell, Barry Fry, and Noel Cantwell.

During the next three years 1963, 1964, and 1965 I went on to make 138 appearances in the reserve team at Anfield scoring 34 goals.

In 1964/65 I was easily the top scorer in the Liverpool reserve team, and although I moved in to the first team squad, I never made my first team debut, as they only used 13 players in total that year, and the substitute rule only became effective in 1966/67, after I had left the club.

It was so different then from the Liverpool of the modern era. When reporters asked Bill Shankly what the team was, he used to reply “Same as last season”

During my time at Liverpool as a young player, I saw at first hand the fantastic charisma and motivational powers of Bill Shankly, and I was a witness to the authenticity of many of the stories of this amazing man that have found their way in to the folk lore of British football.

I was there when he ordered the building of the famous shooting boards and sweat boxes at the Melwood training ground, where the training and coaching methods instilled by Bill Shankly and Bob Paisley were ultimately copied all over the world.

There were three full sized pitches at Melwood but the main pitch in front of the dressing rooms at Melwood was his pride and joy, and over one weekend he had the turf re-laid to ensure it was as good as Wembley Stadium.

When we arrived at Melwood for training on the Monday morning Shankly had jokingly put a notice on the notice board which said “In future only players with a minimum of 5 caps are allowed on the big pitch.” By order of the Manager.

In the 1964-65 season first team beat Leeds United to win the FA Cup at Wembley. This was the first time that Liverpool had ever won the Cup, and it was a fabulous occasion, and the greatest day in the clubs history at that time.

I remember walking up the Wembley pitch with Bill Shankly, Bob Paisley and Peter Thompson an hour and a half before the game. Bill looked at the masses of Liverpool fans behind the goal and said to Bob Paisley. “Bob we can’t lose for these fans, it is not an option” The hairs still stand up on the back of my neck today when I think about it.

I remember Ian St John’s great headed winning goal in extra time, and the winner’s reception at the Grosvenor House Hotel in London.

On the train journey home we drank champagne from the FA Cup, and once we passed Crewe you could not see the buildings for flags and bunting.

When we arrived at Lime Street station there must have been over 500,000 people in the streets as we made our way to the town hall for the official reception.

I stood behind Shankly on the town hall balcony as he made his speech to the thousands of supporters congested in to Water Street below, and it was absolutely electrifying. At the time I was in digs with the great Liverpool winger Peter Thompson and when we eventually got home to our digs that evening I found a letter from the club waiting for me from Mr Shankly. I opened it thinking that I had been permanently promoted to the first team squad and that 1966 would be my big breakthrough year.

I was brought right back to reality when I saw that the letter stated that at a board meeting of the Directors of Liverpool FC it had been decided to place me on the transfer list.

On the Monday morning I went in to see the great man as I was very upset. He then proceeded to make the most wonderful sacking any manager has ever implemented.

He said to me “George son there are five good reasons why you should leave Anfield now.” I was puzzled and asked what they were. “Callaghan, Hunt, St John, Smith, and Thompson” he replied “The first team forward line, they are all internationals”.

I was in tears by now, and it was then that he showed his motivational powers, humanity and greatness when he said the words I will never forget. “George son always remember that at this moment in history you are the twelfth best player in the world” When I asked what he meant by this outrageous statement he replied “The first team here at Anfield son is the greatest team in the world and you are the leading goalscorer in the reserves. I have sold you to Aberdeen go back home and prove me right”

As I was leaving his office very upset, he made his final comment. ”Son remember this, you were one of the first players to come here and sign for me so I want you to think of yourself like the foundation stone of the Liverpool Cathedral. “Nobody ever sees it but it has to be there otherwise the cathedral does not get built.”

He also gave me a written reference that day which is still my proudest possession and which says the following.

"Dear People, George Scott played for my football club for five years from 1960 to 1965 and during that time he caused no trouble to anybody. I would stake my life on his character. Bill Shankly".