Football Association Challenge Cup

In 1871, Charles W. Alcock, the Secretary of the Football Association, announced the introduction of the Football Association Challenge Cup. It was the first knockout competition of its type in the world. Only 12 clubs took part in the competition: Wanderers, Royal Engineers, Queens Park, Hitchin, Barnes, Civil Service, Crystal Palace, Hampstead Heathens, Great Marlow, Upton Park, Maidenhead and Clapham Rovers.

Many clubs did not enter for financial reasons. All ties had to be played in London. Clubs based in places such as Nottingham and Sheffield found it difficult to find the money to travel to the capital. Each club also had to contribute one guinea towards the cost of the £20 silver trophy.

In the 1872 final, the Wanderers beat the Royal Engineers 1-0 at the Kennington Oval. They also won it the following season with with Arthur Kinnaird getting one of the goals.

Other winners of the competition included Oxford University (1874), Royal Engineers (1875), Old Etonians (1879 and 1882) and Old Carthusians (1881).

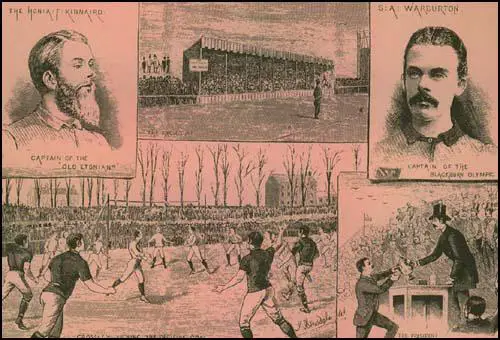

In 1882, Blackburn Rovers became the first provincial team to reach the final of the FA Cup. Their opponents was Old Etonians who had reached the final on five previous occasions. However, Blackburn had gone through the season unbeaten and was expected to become the first northern team to win win the game. Doctor Greenwood was injured the team included five players who had won international caps, Jimmy Douglas, Fred Hargreaves, John Hargreaves, Hugh McIntyre and Jimmy Brown.

The Old Etonians scored after eight minutes and despite creating a great number of chances, Blackburn was unable to obtain an equalizer in the first-half. Early in the second-half George Avery was seriously injured and Blackburn Rovers was reduced to ten men. Despite good efforts by Jimmy Brown, Jack Hargreaves and John Duckworth, Rovers were unable to score.

The following year Blackburn Rovers were in favourites to win the FA Cup. However, an injury hit Rovers were beaten 1-0 in the second round by local rivals Darwen. The Blackburn Times reported that this was a major surprise as the "play was so much in the Rovers' favour that Howorth (the goalkeeper) never handled the ball throughout the match."

Blackburn Olympic decided to enter the FA Cup in 1882-83. Coached by former England player, Jack Hunter, Blackburn beat Lower Darwen 9-1 in the second round of the competition. This was followed by victories against Darwen Ramblers (8-0), Church (2-0) and Druids (4-0). Hunter, who also played at centre-half for Olympic, led his team to a 4-0 victory over Old Carthusians in the semi-final of the competition.

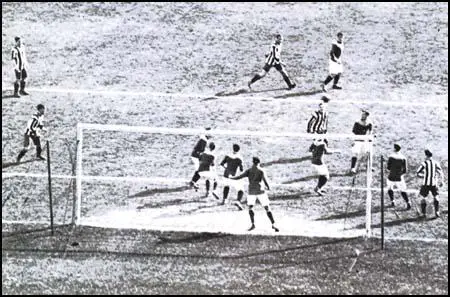

Over 8,000 people arrived at the Oval to watch Blackburn Olympic play Old Etonians in the final. Blackburn selected the following team: Thomas Hacking (dental assistant), James Ward (cotton machine operator), Albert Warburton (master plumber and pub landlord), Thomas Gibson (iron foundry worker), William Astley (weaver), John Hunter (pub landlord), Thomas Dewhurst (weaver), Arthur Matthews (picture framer), George Wilson (clerk), Jimmy Costley (spinner) and John Yates (weaver).

Old Etonians were appearing in their third successive FA Cup Final. Their captain, Arthur Kinnaird, was playing in his ninth final and his side were hot favourites to win. Goodhart gave the public school side a 1-0 lead at half-time. The fitter Blackburn Olympic began to take control of the game in the second-half and Arthur Matthews scored a well-deserved equalizer. Despite being the much better team Olympic was unable to score a winning goal during normal time. After 17 minutes of extra time, Thomas Dewhurst ran at the defence, centred the ball to Jimmy Costley, who volleyed the ball past the goalkeeper. Blackburn Olympic had become the first northern team to win the FA Cup. No amateur club was to win the trophy again.

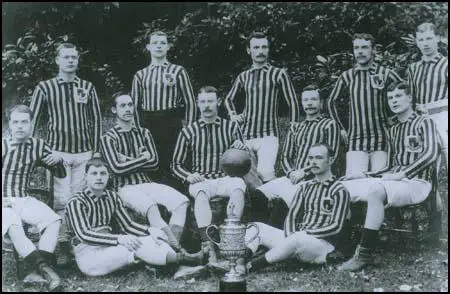

In the 1883-84 FA Cup Blackburn Rovers beat Padium (3-0), Staveley (5-0), Upton Park (3-0), and Notts County (1-0) to reach the final. After Blackburn beat Notts County the club made an official complaint to the Football Association that John Inglis was a professional player. The FA carried out an investigation into the case discovered that Inglis was working as a mechanic in Glasgow and was not earning a living playing football for Blackburn Rovers.

John Inglis played in the final against Queens Park at outside left. Other Scots in the team included Jimmy Douglas (outside right) Fergie Suter (left-back) and Hugh McIntyre (centre-half). The Scottish club scored the first goal but Blackburn Rovers won the game with goals from Blackburn lads, James Forrest and Joe Sowerbutts.

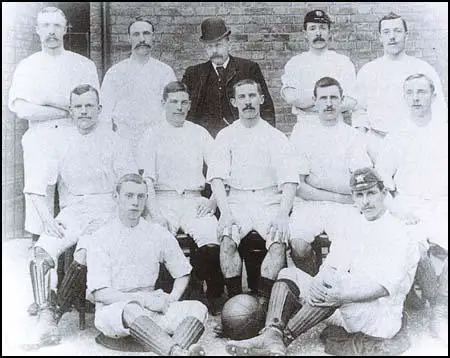

Cup that they won in 1883-84 season. Back row, left to right: Joseph Lofthouse,

Hugh McIntyre, Joe Beverley, Herbie Arthur, Fergie Suter, James Forrest,

Richard Birtwistle, Front row: Jimmy Douglas, Joe Sowerbutts, Jimmy Brown,

George Avery and John Hargreaves.

In January, 1884, Preston North End played the London side, Upton Park, in the FA Cup. After the game Upton Park complained to the Football Association that Preston was a professional, rather than an amateur team. Major William Sudell, the secretary/manager of Preston North End, admitted that his players were being paid but argued that this was common practice and did not breach regulations. However, the Football Association disagreed and expelled them from the competition.

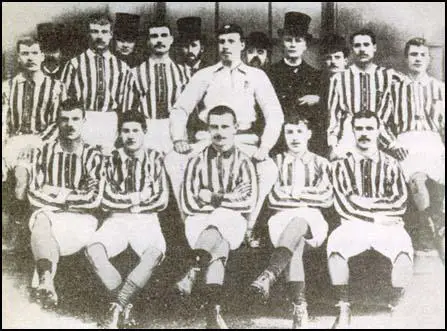

Blackburn Rovers, who denied they were paying their players, beat Witton (6-1), Romford (8-0), West Bromwich Albion (2-0) and Old Carthusians (5-0) to reach the final. Once again they had to play Queens Park. Blackburn Rovers was now a team full of internationals. This included James Forrest, Herbie Arthur, Joseph Lofthouse, Hugh McIntyre, Jimmy Brown and Jimmy Douglas. A crowd in excess of 12,000 arrived at the Oval to see the what most people believed were the best two clubs in England and Scotland. With goals from Brown and Forrest, Blackburn Rovers won 2-0.

In the 1885-86 season West Bromwich Albion beat Wolverhampton Wanderers (3-1), Old Carthusians (1-0), Old Westminsters (6-0) and Small Heath Alliance (4-0) to reach the final of the competition. Their opponents were Blackburn Rovers, who were appearing in their third successive final. Four of the players, Fergie Suter, Hugh McIntyre, Jimmy Brown and Jimmy Douglas were playing in their fourth final in five season. The game at the Kennington Oval ended in a 0-0 draw.

The replay took place at the Racecourse Ground, Derby. A goal by Joe Sowerbutts gave Blackburn Rovers an early lead. In the second-half James Brown collected the ball in his own area, took the ball past several WBA players, ran the length of the field and scored one of the best goals scored in a FA Cup final. Blackburn now joined the Wanderers in achieving three successive cup final victories.

West Bromwich Albion had done very well to reach the final. Seven members of the team that reached the 1886 FA Cup Final still worked at Salter's Spring Factory. This included Bob Roberts, Charlie Perry, George Woodhall, George Timmins, George Bell, Harry Bell and Ezra Horton. All eleven players were born within a six-mile radius of West Bromwich.

Aston Villa did very well in the 1886-87 season. They lost very few games and scored over 130 goals in the process. Stars of the team included Archie Hunter, Richmond Davis, Albert Brown, Arthur Brown, Dennis Hodgetts and Howard Vaughton. Aston Villa also had a good run in the 1886-87 FA Cup. They beat Wolverhampton Wanderers (2-0), Horncastle (5-0), Darwen (3-2) and Glasgow Rangers (3-1) to reach the final for the first time. Their local rivals, West Bromwich Albion, also reached the final.

The final was to be played at the Kennington Oval. The experienced Archie Hunter believed that this ground would be to the advantage of Aston Villa: "Our style of play is suited to a big ground, and the Albion with their long passing have the advantage on a small field. On the Oval we both shall have an equal chance, and where things are equal the short passing game is always the best. These are my reasons for thinking we will win on Saturday."

West Bromwich Albion was the better team in the first-half. However, in the second-half Aston Villa took control and it was no surprise when Richmond Davis, the team's outside-right, crossed for Dennis Hodgetts to sidefoot the ball in the net. WBA players claimed that Hodgetts was offside but the referee, Francis Marindin, who was also president of the Football Association, refused to change his mind.

In the 89th minute Archie Hunter raced through the West Bromwich Albion defence. He appeared to have pushed the ball too far ahead of him and the WBA goalkeeper, Bob Roberts, dashed forward but Hunter, stretching to the full, managed to get one final touch on the ball. As Hunter and Roberts collided the ball trickled over the line. Hunter was the first player to score in every round of the FA Cup competition.

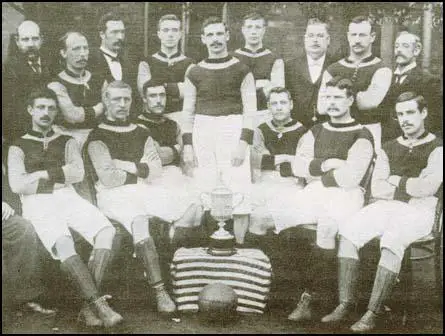

James Warner, Fred Dawson, Joe Simmonds, Albert Allen. Middle row: (left to right):

Richmond Davis, Albert Brown, Archie Hunter, Howard Vaughton, Dennis Hodgetts.

Harry Yates and John Burton are seated on the floor.

In 1887 Sunderland beat Middlesbrough 4-2 in an early round of the FA Cup. Middlesbrough protested that three of Sunderland's players (Monaghan, Hastings and Richardson) were living in Scotland and was lodged at the Royal Hotel at the club's expense. In January 1888, the Football Association examined the Sunderland books and discovered "a payment of thirty shillings in the cash book to Hastings, Monaghan and Richardson for train fares from Dumfries to Sunderland". Sunderland was kicked out of the FA Cup and ordered to pay the expenses of the inquiry. The three players concerned were each suspended from football in England for three months.

West Bromwich Albion was in great form in the 1887-88 season, scoring 195 goals in 58 first-team matches. The club also enjoyed another good run in the FA Cup beating Stoke City (4-1), Old Carthusians (4-2) and Derby Junction (3-0) to reach the final against Preston North End.

A crowd of nearly 20,000 watched the final at the Kennington Oval on 24th March, 1888. The 19-year-old Billy Bassett was the star of the game and after one long dribble he passed to Jem Bayliss who scored the opening goal. Fred Dewhurst scored an equalizer early in the second-half but WBA gradually got the upper-hand. According to Philip Gibbons in Association Football in Victorian England: "Bassett tormented their defence". He eventually provided the cross for George Woodhall to score the winning-goal ten minutes from time.

Albert Aldridge, Charlie Perry, Ezra Horton, Bob Roberts, George Timmins, Harry Green;

front row, George Woodhall, Billy Bassett, Jem Bayliss, Tom Pearson, Joe Wilson.

In his book, The Essential History of West Bromwich Albion, Gavin McOwan argues: "He (Bassett) would bewilder defenders by suddenly stopping the ball dead in the middle of a sprint, leaving his marker to carry on running while he had already changed tack or delivered his cross." Ernest Needham, the English international, described Bassett as "without doubt, the best outside right in the British Isles".

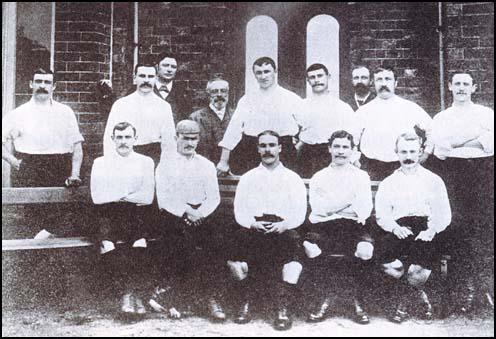

The first season of the Football League began in September, 1888. Preston North End won the first championship that year without losing a single match and acquired the name the "Invincibles". Eighteen wins and four draws gave them a 11 point lead at the top of the table. Preston also beat Wolverhampton Wanderers 3-0 to win the 1889 FA Cup Final. The goals were scored by Jimmy Ross, Fred Dewhurst and Samuel Thompson. Preston won the competition without conceding a single goal.

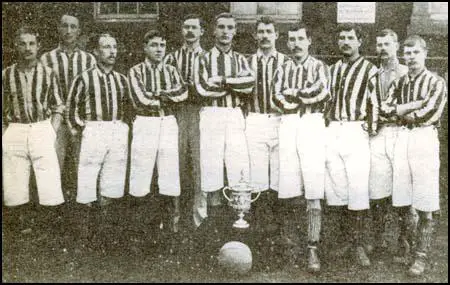

Bob Holmes, Robert Howarth, William Sudell, John Graham and Robert Mills-Roberts are in the

back row. John Gordon, Jimmy Ross, John Goodall, Fred Dewhurst and Samuel Thompson

are sitting on the bench.

In the 1889-90 season Blackburn Rovers were odds-on favourites to win the cup against Sheffield Wednesday, who played in the Football Alliance league. Blackburn selected the following players: (G) John Horne, (2) Johnny Forbes, (3) James Southworth, (4) John Barton, (5) George Dewar, (6) James Forrest, (7) Joseph Lofthouse, (8) Harry Campbell, (9) Jack Southworth, (10) Nathan Walton and (11) Billy Townley.

Blackburn Rovers took the lead in the 6th minute when a shot from Townley was deflected past the Sheffield Wednesday goalkeeper. Campbell hit the post before Walton converted a pass from Townley. Blackburn scored a third before half-time when Southworth scored from another of Townley's dangerous crosses from the wing.

Townley scored his second, and Blackburn's fourth goal in the 50th minute. Bennett got one back for the Sheffield side when Bennett headed past the advancing Horne. Townley completed his hat-trick when he converted a pass from Lofthouse. Ten minutes before the end of the game, Lofthouse completed the scoring and Blackburn had won the cup 6-1. As Philip Gibbons pointed out in his book Association Football in Victorian England: "The Blackburn side had given one of the finest exhibitions of attacking football in an FA Cup Final, with England internationals, Walton, Townley, Lofthouse and John Southworth at the peak of their form."

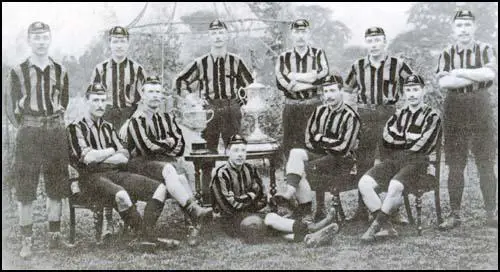

James Southworth, Jack Southworth, Richard Birtwistle, John Horne, George Dewar

Middle row: Joseph Lofthouse, Harry Campbell, Johnny Forbes, Nathan Walton,

Billy Townley. Front row: John Barton and James Forrest.

Blackburn had another good run in the FA Cup and beat Middlesborough Ironopolis (3-0), Chester (7-0), Wolverhampton Wanderers (2-0), West Bromwich Albion (3-2) to reach their second successive final.

Notts County were their opponents. Blackburn selected the following players: (G) Rowland Pennington, (2) Tom Brandon, (3) Johnny Forbes, (4) John Barton, (5) George Dewar, (6) James Forrest, (7) Joseph Lofthouse, (8) Nathan Walton, (9) Jack Southworth, (10) Coombe Hall and (11) Billy Townley.

Birtwistle, Tom Brandon, Rowland Pennington, John Barton, Jack Southworth,

George Dewar, James Forrest, E. Murray. Front row: Joseph Lofthouse,

Nathan Walton, Johnny Forbes, Coombe Hall and Billy Townley.

Blackburn Rovers put Notts County under pressure from the beginning and in the 8th minute, centre-half Dewar scored from a Townley corner. Before the end of the first-half, Southworth and Townley added further goals. Jimmy Oswald of Notts County did score a late consolation goal but Blackburn finished comfortable 3-1 winners and won the FA Cup for the 5th time in 8 years.

West Bromwich Albion struggled in the Football League in the 1891-92 season. However, they did well in the FA Cup beating Old Westminsters (3-2), Blackburn Rovers (3-1), Sheffield Wednesday (2-1), Nottingham Forest (6-2) to reach the final against Aston Villa.

Mark Nicholson, Jack Reynolds, Roddie McLeod, Joe Reader, Sammy Nicholls,

Charlie Perry, Tom Pearson, Willie Groves, Alf Geddes, Thomas McCulloch.

In his book, Association Football in Victorian England, Philip Gibbons argues that: "Villa dominated the early proceedings, with Athersmith and John Devey exerting pressure on the Albion fullbacks. However, the West Bromwich side soon responded as Billy Bassett passed to Roddy McLeod, who crossed the ball to the waiting Geddes. He shot towards the Villa goal and Warner failed to collect the ball clearly. It rolled between the Villa goalposts to secure a surprising one-goal lead for the Albion team."

Billy Bassett was also involved in WBA's second goal. He won the ball on the halfway line and after running at the Aston Villa defence he passed to Alf Geddes. His shot was saved but the goalkeeper could not hold onto the ball and Sammy Nicholls had the simple task of scoring from the rebound. Jack Reynolds scored the third with a shot from 25-yards.

Wolverhampton Wanderers played Everton at the Fallowfield Ground in Manchester in the 1893 FA Cup Final. Nine of the Wolves team were locally born players. Everton on the other hand fielded six players from Scotland. Over 40,000 people turned up to see the game. Wolves won the game with the only goal scored by Harry Allen.

Howard Spencer, John Devey, Albert Wilkes, James Welford; front row, Charlie Athersmith,

Robert Chatt, James Cowan, George Russell, Dennis Hodgetts and Stephen Smith.

Aston Villa had victories over Derby County (2-1), Newcastle United (7-1), Nottingham Forest (6-2), Sunderland (2-1) to reach the 1895 FA Cup Final against West Bromwich Albion. The Villa outside-left, Robert Chatt, scored the only goal of the game after 39 seconds.

Aston Villa won the First Division title in 1896-97. Second-place Sheffield United finished an amazing 11 points behind Villa. The club scored 73 goals in the league that season. The main contributors included George Wheldon (18), John Devey (17), Johnny Campbell (13), Charlie Athersmith (8), John Cowan (7) Stephen Smith (3) and Jack Reynolds (2).

On 30th January, 1897, Aston Villa beat Newcastle United 5-0 in the third round of the FA Cup. Aston Villa went onto beat Notts County (2-0), Preston North End (3-2) and Liverpool (3-0) to reach the final against Everton. A crowd of 60,000 arrived at Crystal Palace to watch the final. Charlie Athersmith scored the opening goal but Everton hit back with goals from Jack Bell and Richard Boyle. Aston Villa continued to dominate the game and added two more from George Wheldon and Jimmy Crabtree. That finished the scoring and therefore Aston Villa had emulated the great Preston North End side that had achieved the FA Cup and Football League double in 1888-89 season.

Aston Villa also reached the 1905 FA Cup Final. Over 100,000 people watched Villa beat Newcastle United 2-0. Both goals were scored by Harry Hampton.

In 1923 the FA Cup was moved to Wembley. The ground had been built for the British Empire Exhibition and had excellent railway links. Over 270,000 people travelled in 145 special services to the final that featured West Ham United and Bolton.

Primary Sources

(1) Archie Hunter, described Aston Villa's victory over West Bromwich Albion in the 1887 FA Cup Final in his book, Triumphs of the Football Field (1890)

The teams engaged to play in the match were as follows:

Aston Villa: James Warner, goal; F. Coulton and J. Simmonds, backs; H. Yates, F. Dawson and ,J. Burton, half-backs; Albert Brown and Richard Davis, right wing; Howard Vaughton and Dennis Hodgetts, left wing; Archie Hunter, centre (captain) forwards.

West Bromwich: R. Roberts, goal; H. Green and A. T. Aldridge, backs; E. Horton, G. Timmins and C. Perry, half-backs; G. Woodhall and T. Green, right wing; T. Pearson and W. Paddock, left wing; W. Bayliss, centre (captain), forwards.

We started for London on Friday and took up our quarters at Charterhouse Square. In the evening we had a short stroll and then retired at ten o'clock. We were up betimes in the morning, all in good spirits and happily all in good health. We met our committee and a few friends and proceeded to Kennington Oval, where presently we were joined by the members of the Albion, who were also in excellent form and very sanguine as to the result of the match. All the well-known supporters of both clubs were present in good force, including Mr. Hundly, our genial host at Holt Fleet and early in the morning heavily laden trains poured into the stations and discharged their living freight of football enthusiasts. Our chocolate-and-blue colours could be seen everywhere in the morning, especially along the Strand and all the principal thoroughfares. At half-past two there was a general stampede towards Kennington Oval and cabs, cars, carriages, traps and a thick line of pedestrians could be seen moving down the road. Arriving on the ground, it was at once manifest how great an interest the encounter had awakened. There was a dense multitude of from fifteen to twenty thousand, many familiar faces being among the number. At the last moment,5-to-4 on the Albion could be obtained and the betting in their favour was very brisk.

A few minutes before three we entered the field and were greeted with a hearty round of cheering. I had given the Villa team special instructions how to play this match; briefly they were these - every man was to stick to his position and look after the opponent he was facing. This, of course, does not give such opportunities of brilliant play, but it is a measure of safety which I strongly commend. Let every player single out his man and determine to beat him and if he is equal to the effort the game is won. This course demands an amount of unselfishness on the part of the players which is very hard to exercise, but I have so often seen brilliance and danger combined that on such an occasion as the one I speak of we could not afford to run any such risk. Consequently the match from beginning to end was less scientific than the match with the Rangers. In this respect it was doubtless disappointing. But as a hard, fierce struggle it is not to be surpassed.

Bayliss won the toss and I kicked off exactly at half-past three. As I did so a subdued hum of excitement could be heard and we knew that everybody's nerves were strung to the utmost. I don't know whether I am equal to describing all the details of the match. So far as play went I was coot enough, but so intent upon the game that when it was all over I could only remember a confused multitude of incidents in no particular order, but all warm, vigorous and exciting. I remember how we scampered up and down the field, what wild rushes were made, how the ball bounded here and there, the desperate charges that followed, the frenzied scrimmages, the impulsive shooting, the grand work of the goalkeepers, the attack and defence, the dangers and the relief, the terrific and prolonged struggle and yet, up to half-time, not a single goal! I recall with a thrill how we saw at one point that the Albion were getting the better of us and how we saw them with dismay closing round our citadel. Then how exhilarating it was to see the danger past, to know that the attack had been unavailing and to find ourselves racing away with the ball towards the opposite goal. How often Warner and Roberts saved I cannot tell. Time after time the shots went in scorching hot and always the men between the timbers were equal to the emergency and this was why when half the game was over there was no score.

Changing ends, the Albion cut out the work and Hodgetts and Vaughton on our side commenced putting in an immense amount of good work. A determined attack by them was repelled by Tom Green, who got away up the field and was stopped by Coulton, who returned. From this kick Davis with a long shot centred to Hodgetts, who was close in goal and he with consummate ease, put the ball through, completely baffling Roberts. Then what a cheer arose! The Villa had scored and the jubilation of our supporters was boundless. By the time they had settled down again we were in the midst of a fast and dashing game. It seemed, however, as if no further points would be gained. Both sides were playing desperately and every man was working as if his life depended upon the victory. We were constantly in front of goal and a foul being given to the Albion there, matters looked dangerous. But it was only at the end of the game that the finishing stroke was to be given to our victory. I got possession of the ball and eluding the backs got right in front; but the ball was going at such a furious pace that I perceived I could not reach it. Roberts saw reach the ball and give it the necessary push. If I had not adopted this expedient I could not possibly have scored. The cheers had scarcely subsided when the whistle blew and the Villa had won the Cup by two goals to none.

Major Marindin, President of the Football Association, who acted as referee, was good enough to say that the match was not won be science but "by Archie Hunter's captaincy." As soon as the whistle blew I was surrounded by the enthusiastic crowd and for a few moments I thought I should be torn in pieces. They nearly wrung my hand off and those who could not get near enough put all the heart they could into shouting "Bravo, Archie" and "Well done, Villa." Finally, I was lifted shoulder-high and amid the wildest demonstrations carried all round the field, nor would my zealous friends release me until the moment came when I was called upon to receive the Cup.

(2) James Walvin, The People's Game (1975)

The progress of the FA Cup mirrored the changing social progress of football. The decade of dominance by the public school teams was ended at the 1881 final between Old Carthusians and Old Etonians. In the following year the Old Etonians were back again, this time to face Blackburn Rovers. In 1883 another Blackburn team, Olympic, travelled to the London final, taking the trophy north for the first time. Blackburn Olympic, under the control of Jack Hunter, their player-manager, had trained for the final at the booming seaside town of Blackpool and when they stepped out to meet Lord Kinnaird's Old Etonians, the social contrast could not have been greater. Among the Blackburn players were three weavers, a spinner, a dental assistant, a plumber, a cotton operative and an iron-foundry worker. Having won 1-0 in extra time, the Blackburn team was welcomed home by huge crowds headed by yet another manifestation of the new working-class social life - a brass band. Blackburn Olympic had approached the game in a most professional manner. Financed by a local iron-foundry owner, they had trained carefully for a week and had stuck to a suitable diet.

(3) Gavin McOwan, The Essential History of West Bromwich Albion (2002)

Although football had been around for Centuries, it was the great Victorian public schools and Cambridge University which first codified and popularized the game around the 1860s, so it was natural that these teams dominated 'modern football' in its infancy. But by the 1880s the game had spread rapidly through the expanding industrial heartlands of the Midlands and Lancashire. If the demographic map of Britain changed dramatically over the course of the 19th century, as the population expanded to the new industrial centres of the North and Midlands, the footballing map changed shape over an even shorter period. When Blackburn Olympic beat the Old Etonians in the FA Cup final in 1883, they made history by becoming the first provincial team to win the trophy. The die had been cast and never again was an old boys' team from the south to reach a final. And once professionalism was legalized in England two years later tile heyday of the ex-public school teams was over. From then on football has remained a working-class game all over the world in which clubs from large cities - often industrial centres or ports - have dominated. The middle and upper classes have been left largely to administer the game and run the clubs.

Along with their new ground and new professional status, Albion had also gained some important new additions to their playing squad in this period. The splendid Charlie Perry had played in the second team for two seasons before making his full debut in 1884, as did the powerful, Tipton-born striker Jem Bayliss and outside right George 'Spry' Woodhall, all of whom would become key members of Albion's great FA Cup sides of the late 1880s. These three future Albion greats were among the first batch of professionals, along with other pioneers such as captain George Bell, Bob Roberts, Harry Green and George Timmins.

(4) Philip Gibbons, Association Football in Victorian England (2001)

Having won the toss, Nick Ross, the Preston captain, decided to play with the sun on their backs, which resulted in difficulties for the Albion defence as the Preston forwards mounted early attacks. However, excellent defending by Perry and Aldridge, together with fine goalkeeping by Bob Roberts, kept the Preston forwards at bay.

Fred Dewhurst and John Goodall had a number of chances to score the game's opening goal, but were again thwarted by Bob Roberts when it seemed easy to score. Against the run of play, Billy Bassett dribbled the ball down the Preston left flank, prior to crossing to Jem Bayliss, who secured a one-goal lead for the West Bromwich side. As the game headed towards half-time, Jimmy Ross and Fred Dewhurst forced excellent saves out of Bob Roberts, and Albion ended the half one goal to the good.

Little changed during the second period of play as Preston sought the equalising goal, which eventually arrived after ten minutes of play when Preston's efforts were rewarded with a goal by Fred Dewhurst. The Lancashire side now began to play their finest football of the game as they continued to put pressure on the Albion fullbacks. However, with Aldridge and Green outstanding, they were unable to secure a second goal.

Up to the halfway stage of the second half, Albion's occasional attacks were efficiently dealt with by Nick Ross and Bob Howarth. As the half progressed, the Midlands side came more into the game. Bassett and Woodhall took on the Preston defence, while at the other end of the field, John Goodall saw a shot rebound from the Albion upright to safety. As the game reached the final stages, Albion looked the fresher side. The Preston defence had begun to tire, with only Nick Ross preventing the West Bromwich side from scoring a second goal as Bassett tormented their defence. However, with a little more than ten minutes remaining, Albion took the lead when a centre from Bassett found Woodhall, who turned sharply to steer the ball between the Preston goalposts. Preston rallied in pursuit of an equaliser, but to no avail, as the final whistle sounded with Albion the victors by two goals to one in one of the most competitively fought FA Cup Finals to date.

(5) Stan Mortensen, Football is My Game (1949)

I cried after the Cup Final of 1948... but it wasn't because I had been on the losing side at Wembley. We had lost the last great round ; had failed to win the Cup, yet I walked off that marvellous pitch in that wonderful stadium with tears of real happiness in my eyes.

The picture will remain with me while memory lasts. The game was over, the medals had been presented to both sides, and the Cup itself to Johnny Carey, the Manchester United captain. The Black¬pool players had stood in a group, talking of this and that, while the victorious team walked up to the Royal Box to receive their mementoes and handshakes from the King and Queen. Then our turn had come, and we had filed past the Royal Family with their warm smiles, their words of sympathy for the losers coming just as sincerely as their earlier words of congratulation for the winners.

In accordance with tradition, the United players had chaired their captain off the pitch, all the way to the dressing-room.

We Blackpool players walked off slowly behind our victors. We had lost-lost after twice leading, a record of its kind at Wembley - yet I don't think we were too dispirited. Sorry, yes, but still excited from the heat of the struggle, with our thoughts in a tangle.

We walked off the turf, on to the track which surrounds the finest playing pitch in the British Isles. I happened to glance up to the crowd, loath to go away, staying on to see the curtain rung down on the drama of the Cup Final.

There, standing over the tunnels which led to the dressing-rooms, was a party of Blackpool supporters. Beribboned and bedecked in our famous tangerine, with caps, streamers, rosettes, scarves, ail telling of their loyal support for the Bloomfield Road club, they stood, silently surveying the last moments of the last incidents of a memorable day.

In the spring sunshine I could see almost every individual plainly. They stood there, mute in their disappointment, gazing down as their favourite team walked off-without the Cup which they had hoped we would carry back to the seaside.

Their silent sympathy with us, their regret at the result, was obvious ; and across the intervening space, from crowd to players, there seemed some link, some bond of fellowship. Hardly thinking what I was doing, I waved to that silent crowd.

The effect was magical. They responded with a shout which seemed as mighty as anything we had heard during the pulsating struggle of the match itself. With a thunderous roar they let loose all their hot fanaticism for us and for the game of soccer.

I thought, as though in a dream lasting only a second or two, of the path to Wembley: how the Blackpool team had been reshaped after the war, how we had started this one great season with such high hopes ; how we had won first one game and then another; how we had knocked out the giant-killing Colchester United ; how we had gone to the semi-final against Tottenham Hotspur ; how we had struggled against an unlucky one-goal deficit; how we had won equality in the last minutes of the match; how we had scored two more in extra time to earn the match at Wembley.

I thought of the scramble for tickets; and I thought, too, of the patience and keenness of those cheering supporters, many of whom had travelled all through the night to get to Wembley. And above all, I thought of the greatness of a game that could develop such sportsmanship, such warm support, such loyalty, and, at the end of a losing match, such spontaneous comradeship with the beaten team.

All these thoughts flashed through my mind as I walked those last few yards to the darkness under the Wembley terraces. As I passed from the view of the cheering throng, I waved again. They could still see me, but I could not see them. My eyes were filled with tears.