West Bromwich Albion: 1879-1900

The West Bromwich Strollers club was formed in 1879 by a group of young men from the Salter's Spring Factory in West Bromwich. Initially they played cricket at Dartmouth Park but in 1882 they decided to form the West Bromwich Albion football club. That year they moved to the Four Acres ground.

The star of the original team was Bob Roberts. He played in virtually every outfield position before eventually becoming the team goalkeeper.In his book, The Essential History of West Bromwich Albion, Gavin McOwan points out: "The 6ft 4in tall, 13-stone Roberts became known as the Prince of Goalkeepers... His hefty physique (he wore size 13 boots) was a huge asset in the days when forwards would try to steamroller keepers through the goal - with or without the ball."

WBA entered the FA Cup in the 1883-84 season but lost in the first round to Wednesbury Town. The following year they played Aston Villa away in the 3rd round. Over 22,000 people saw WBA beat their local rivals 3-0. After beating Druids they faced the mighty Blackburn Rovers in the 5th round. A record home attendance of 16,393 saw Blackburn win 2-0.

In the 1885-86 season WBA beat Wolverhampton Wanderers (3-1), Old Carthusians (1-0), Old Westminsters (6-0) and Small Heath Alliance (4-0) to reach the final of the competition to be played at the Kennington Oval. Fred Bunn was WBA's first-team centre-half at the time. However, he got injured and Charlie Perry replaced him for the final.

WBA's opponents were Blackburn Rovers, who were appearing in their third successive final. Four of the players, Fergie Suter, Hugh McIntyre, Jimmy Brown and Jimmy Douglas were playing in their fourth final in five season. WBA dominated the match but Herbie Arthur, the Blackburn goalkeeper, made several good saves and the game ended in a 0-0 draw.

The replay took place at the Racecourse Ground, Derby. A goal by Joe Sowerbutts gave Blackburn Rovers an early lead. In the second-half James Brown collected the ball in his own area, took the ball past several WBA players, ran the length of the field and scored one of the best goals scored in a FA Cup final. Blackburn now joined the Wanderers in achieving three successive cup final victories.

This was a magnificent achievement for a team of amateurs. Seven members of the team that reached the 1886 FA Cup Final still worked at Salter's Spring Factory. This included Bob Roberts, Charlie Perry, George Woodhall, George Timmins, Ezra Horton, George Bell, and Harry Bell. All eleven players were born within a six-mile radius of West Bromwich. At the time the town had a population of 56,000 people.

Bob Roberts was WBA's star player in these early years. A local newspaper commented: "There is no player who has done more to make the Albion the club what it is than Bob Roberts. It is not only his cleverness between the uprights, but the coolness and direction of others."

In the 1886-87 season they beat Burton Wanderers (6-0), Derby Junction (2-1), Mitchell's St George (1-0), Lockwood Brothers (2-1), Notts County (4-1), Preston North End (3-1) to reach the final against Aston Villa. For the second successive year WBA lost the final 2-0 and Woodhall was denied a second cup-winning medal.

WBA was in great form in the 1887-88 season, scoring 195 goals in 58 first-team matches. The club also enjoyed another good run in the FA Cup beating Stoke City (4-1), Old Carthusians (4-2) and Derby Junction (3-0) to reach the final against Preston North End.

A crowd of nearly 20,000 watched the final at the Kennington Oval on 24th March, 1888. The 19-year-old Billy Bassett was the star of the game and after one long dribble he passed to Jem Bayliss who scored the opening goal. Fred Dewhurst scored an equalizer early in the second-half but WBA gradually got the upper-hand. According to Philip Gibbons in Association Football in Victorian England: "Bassett tormented their defence". He eventually provided the cross for George Woodhall to score the winning-goal ten minutes from time.

In his book, The Essential History of West Bromwich Albion, Gavin McOwan argues: "He (Bassett) would bewilder defenders by suddenly stopping the ball dead in the middle of a sprint, leaving his marker to carry on running while he had already changed tack or delivered his cross." Ernest Needham, the English international, described Bassett as "without doubt, the best outside right in the British Isles".

WBA was clearly one of the best football teams in England. Five members of the team, Billy Bassett, Bob Roberts, Jem Bayliss, Charlie Perry, and George Woodhall were selected to play for England in the Home Championship against Scotland, Wales and Ireland.

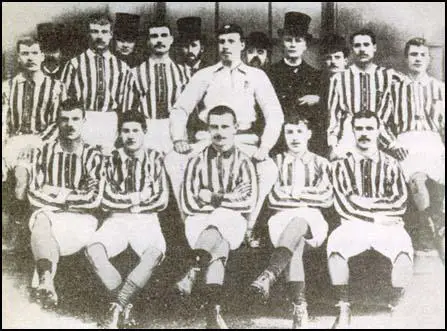

Albert Aldridge, Charlie Perry, Ezra Horton, Bob Roberts, George Timmins, Harry Green;

front row, George Woodhall, Billy Bassett, Jem Bayliss, Tom Pearson, Joe Wilson.

On 2nd March, 1888, William McGregorcirculated a letter to Aston Villa, Blackburn Rovers, Bolton Wanderers, Preston North End, and West Bromwich Albion suggesting that "ten or twelve of the most prominent clubs in England combine to arrange home and away fixtures each season." John J. Bentley of Bolton Wanderers and Tom Mitchell of Blackburn Rovers responded very positively to the suggestion. They suggested that other clubs should be invited to the meeting being held on 23rd March, 1888.

The following month the Football League was formed. It consisted of six clubs from Lancashire (Preston North End, Accrington, Blackburn Rovers, Burnley, Bolton Wanderers and Everton) and six from the Midlands (Aston Villa, Derby County, Notts County, Stoke, West Bromwich Albion and Wolverhampton Wanderers).

The first season of the Football League began in September, 1888. WBA's professional players received 10 shillings a week, with no bonuses or expenses. Preston North End won the first championship without losing a single match and acquired the name the "invincibles". West Bromwich Albion finished in 6th place with Billy Bassett ending up as the club's top scorer with 14 goals in 25 games. Second in the list was Tom Pearson who scored 12 in 26.

Preston North End also won the First Division title in the 1889-90 season. WBA finished in 5th place. Top scorer for the club that season was Tom Pearson with 17 goals in 24 games.

When England international Bob Roberts left the club in 1889 Joe Reader replaced him as WBA's first-team goalkeeper. Reader went on to play for England and the Football League. In his book, The Essential History of West Bromwich Albion, Gavin McOwan describes a game Reader played against the Irish League: "With Reader's defence caught out by a counter attack, he rushed 50 yards out of his goal to thwart the Irish charge. But rather than merely booting the ball away, Reader coolly controlled it, beat his man and then played the ball forward to a team-mate."

In 1891 Charlie Perry replaced Jem Bayliss as captain of West Bromwich Albion. In his book, The Essential History of West Bromwich Albion, Gavin McOwan argues: "Charlie Perry was the heart of the defence... He was cool under pressure and a great marshal of his troops, yet despite the physical nature of the game in this time, he was never cautioned."

WBA struggled in the Football League in the 1891-92 season. However, they did enjoy a 12-0 victory over Darwen. It is still the record score of a match played in the First Division of the Football League. Goalscorers that day included Tom Pearson (4), Billy Bassett (3) and Jack Reynolds (2).

WBA had another good run in the FA Cup beating Old Westminsters (3-2), Blackburn Rovers (3-1), Sheffield Wednesday (2-1), Nottingham Forest (6-2) to reach the final against Aston Villa. In his book, Association Football in Victorian England, Philip Gibbons argues that: "Villa dominated the early proceedings, with Athersmith and John Devey exerting pressure on the Albion fullbacks. However, the West Bromwich side soon responded as Billy Bassett passed to Roddy McLeod, who crossed the ball to the waiting Geddes. He shot towards the Villa goal and Warner failed to collect the ball clearly. It rolled between the Villa goalposts to secure a surprising one-goal lead for the Albion team."

Billy Bassett was also involved in WBA's second goal. He won the ball on the halfway line and after running at the Aston Villa defence he passed to Alf Geddes. His shot was saved but the goalkeeper could not hold onto the ball and Sammy Nicholls had the simple task of scoring from the rebound. Jack Reynolds scored the third with a shot from 25-yards.

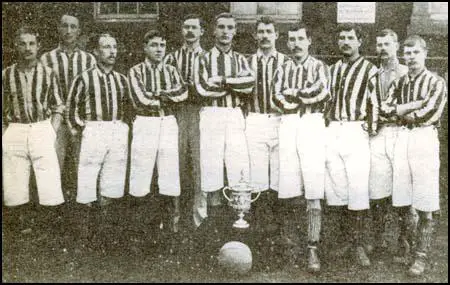

Mark Nicholson, Jack Reynolds, Roddy McLeod, Joe Reader, Sammy Nicholls,

Charlie Perry, Tom Pearson, Willie Groves, Alf Geddes, Thomas McCulloch.

In 1893 Jack Reynolds and Willie Groves joined local rivals Aston Villa. WBA was furious about what they considered to be the poaching of two of their best players. WBA appealed to the Football Association and Villa was eventually fined £25 for approaching Reynolds and Groves without the consent of WBA. They were also forced to pay £50 for the transfer of Reynolds. Tony Matthews described Reynolds in his book, Who's Who of Aston Villa as "a marvellously competitive player, Reynolds mastered every trick in the book and, aided by some remarkable ball skills, his footwork was, at times, exceptionally brilliant."

On 28th April 1894, Billy Bassett became the first ever WBA player to be sent off. According to the referee he was dismissed for using "unparliamentary language" in a match against Millwall.

Over the next few years WBA had only moderate success in the Football League. However, WBA continued to do well in the FA Cup. In the 1894-95 season they had victories over Small Heath (2-1), Sheffield United (2-1) and Wolverhampton Wanderers (1-0). WBA beat Sheffield Wednesday 2-0 in the semi-final but Charlie Perry suffered a serious injury and missed the final against Aston Villa. The Villa outside-left, Robert Chatt, scored the only goal of the game after 39 seconds.

In the 1895-96 season WBA finished bottom. Relegation and promotion was decided by a series of Test Matches in which the top two teams in the Second Division played against the bottom two in the First Division. WBA maintained their position in the top league by beating Liverpool and Manchester City.

WBA continued to struggle in the Football League and over the next few years finished 16th (1895-96), 12th (1896-97), 7th (1897-98) and 14th (1898-99). This lack of success had financial implications for the club. At the end of the 1898-99 season the club was overdrawn at the bank and there was no money to pay the players' summer wages. A business consortium of local publicans and traders agreed to invest £2,500 in WBA.

Part of the deal involved building a new ground on the Hawthorns Estate just outside West Bromwich. On 14th May 1900 the club signed a 14 year, £70 per annum lease with the Sandwell Park Colliery Company, the owners of the site. The ground cost £3,000 to build. The first game at the new ground was watched by 20,104 people. However, five days later, 35,417 fans watched the game against local rivals, Aston Villa. The game brought in record receipts of £1,021 16s 9d.

WBA did not play well that year and the average attendance at the Hawthorns was only 12,000. At the end of the season they were relegated to the Second Division.

Primary Sources

(1) John Gaunt, West Bromwich Albion (1965)

The smoking factory chimneys of the Industrial Revolution gave this corner of Staffordshire the name of the Black Country. The hard-working citizens were craftsmen; their products were made to last and to be appreciated. In their leisure - what there was of it then - they turned to their football clubs with the same pride. They had then, as now, little time for the pretentious or the shoddy. In this atmosphere rose the West Bromwich Albion.

(2) Gavin McOwan, The Essential History of West Bromwich Albion (2002)

Although football had been around for Centuries, it was the great Victorian public schools and Cambridge University which first codified and popularized the game around the 1860s, so it was natural that these teams dominated 'modern football' in its infancy. But by the 1880s the game had spread rapidly through the expanding industrial heartlands of the Midlands and Lancashire. If the demographic map of Britain changed dramatically over the course of the 19th century, as the population expanded to the new industrial centres of the North and Midlands, the footballing map changed shape over an even shorter period. When Blackburn Olympic beat the Old Etonians in the FA Cup final in 1883, they made history by becoming the first provincial team to win the trophy. The die had been cast and never again was an old boys' team from the south to reach a final. And once professionalism was legalized in England two years later tile heyday of the ex-public school teams was over. From then on football has remained a working-class game all over the world in which clubs from large cities - often industrial centres or ports - have dominated. The middle and upper classes have been left largely to administer the game and run the clubs.

Along with their new ground and new professional status, Albion had also gained some important new additions to their playing squad in this period. The splendid Charlie Perry had played in the second team for two seasons before making his full debut in 1884, as did the powerful, Tipton-born striker Jem Bayliss and outside right George 'Spry' Woodhall, all of whom would become key members of Albion's great FA Cup sides of the late 1880s. These three future Albion greats were among the first batch of professionals, along with other pioneers such as captain George Bell, Bob Roberts, Harry Green and George Timmins.

Then came a lively incident. I sent the ball into the hands of Roberts and while he was in the act of stooping to pick it up Albert Brown rushed forward and sent him and the leather through the timbers. Poor Roberts received a kick which rendered him hors de combat for a time, though the occurrence was purely accidental.

With a score of three against our opponents' none we resumed play with a good heart, but the tide turned and Bayliss, one of the forwards, scored for the Albion. But now, if I may say it, came the sensation of the day by my executing one of those "famous runs" which people speak of to this day. I took the ball the whole length of the field, passed four men and eluding all opponents, kicked and scored. This achievement is added to the list of 'Archie's big runs' which it seems footballers are in the habit of recalling whenever they meet to talk of Villa victories.

Against such a team as the Albion the performance was considered almost phenomenal. Thus the game ended and at last we had had the satisfaction of defeating our tough opponents by four to one.

(3) Archie Hunter, described a game against West Bromwich Albion in the 1884-85 season, in his book, Triumphs of the Football Field (1890)

We were drawn against the Albion in the tie for the Mayor of Birmingham's Charity Cup and great local interest centred in the match.

The match was played at the Oval, Wood Green, Wednesbury and it is said that more than 12,000 spectators were present. All the week the Villa team had gone into strict training, for we felt that the encounter would have to be decisive.

The game began evenly, but unfortunately, before many minutes had passed Horton, the captain of the Albion, was hurt and play had to be stopped for a time. On resuming, the Albion began to attack and a free kick to the West Bromwich then nearly proved disastrous. A good run by Eli Davis, Vaughton and myself then won a round of applause from the crowd and I finished with a shot into the opposing citadel which Roberts, the Albion goalkeeper, cleverly saved. The Albion then retaliated, but no score was gained.

Albert Brown next dashed off with the ball and passing it smartly to me gave me a chance of putting it through the posts, the registration of the first point for the Villa calling forth cheers from our supporters. The Albion now began to press us hard and in turn were encouraged by the plaudits of their followers. Vaughton, however, raised the siege and before half-time was called Whateley scored a second point for us. This thoroughly roused our opponents, who began to play a desperately hard game, but we still had several attempts at scoring and Roberts was deservedly applauded for the skilful and dexterous manner in which he repelled our charges.

(4) Philip Gibbons, Association Football in Victorian England (2001)

Having won the toss, Nick Ross, the Preston captain, decided to play with the sun on their backs, which resulted in difficulties for the Albion defence as the Preston forwards mounted early attacks. However, excellent defending by Perry and Aldridge, together with fine goalkeeping by Bob Roberts, kept the Preston forwards at bay.

Fred Dewhurst and John Goodall had a number of chances to score the game's opening goal, but were again thwarted by Bob Roberts when it seemed easy to score. Against the run of play, Billy Bassett dribbled the ball down the Preston left flank, prior to crossing to Jem Bayliss, who secured a one-goal lead for the West Bromwich side. As the game headed towards half-time, Jimmy Ross and Fred Dewhurst forced excellent saves out of Bob Roberts, and Albion ended the half one goal to the good.

Little changed during the second period of play as Preston sought the equalising goal, which eventually arrived after ten minutes of play when Preston's efforts were rewarded with a goal by Fred Dewhurst. The Lancashire side now began to play their finest football of the game as they continued to put pressure on the Albion fullbacks. However, with Aldridge and Green outstanding, they were unable to secure a second goal.

Up to the halfway stage of the second half, Albion's occasional attacks were efficiently dealt with by Nick Ross and Bob Howarth. As the half progressed, the Midlands side came more into the game. Bassett and Woodhall took on the Preston defence, while at the other end of the field, John Goodall saw a shot rebound from the Albion upright to safety. As the game reached the final stages, Albion looked the fresher side. The Preston defence had begun to tire, with only Nick Ross preventing the West Bromwich side from scoring a second goal as Bassett tormented their defence. However, with a little more than ten minutes remaining, Albion took the lead when a centre from Bassett found Woodhall, who turned sharply to steer the ball between the Preston goalposts. Preston rallied in pursuit of an equaliser, but to no avail, as the final whistle sounded with Albion the victors by two goals to one in one of the most competitively fought FA Cup Finals to date.

(5) Archie Hunter, described Aston Villa's victory over West Bromwich Albion in the 1887 FA Cup Final in his book, Triumphs of the Football Field (1890)

The teams engaged to play in the match were as follows:

Aston Villa: James Warner, goal; F. Coulton and J. Simmonds, backs; H. Yates, F. Dawson and ,J. Burton, half-backs; Albert Brown and Richard Davis, right wing; Howard Vaughton and Dennis Hodgetts, left wing; Archie Hunter, centre (captain) forwards.

West Bromwich: R. Roberts, goal; H. Green and A. T. Aldridge, backs; E. Horton, G. Timmins and C. Perry, half-backs; G. Woodhall and T. Green, right wing; T. Pearson and W. Paddock, left wing; W. Bayliss, centre (captain), forwards.

We started for London on Friday and took up our quarters at Charterhouse Square. In the evening we had a short stroll and then retired at ten o'clock. We were up betimes in the morning, all in good spirits and happily all in good health. We met our committee and a few friends and proceeded to Kennington Oval, where presently we were joined by the members of the Albion, who were also in excellent form and very sanguine as to the result of the match. All the well-known supporters of both clubs were present in good force, including Mr. Hundly, our genial host at Holt Fleet and early in the morning heavily laden trains poured into the stations and discharged their living freight of football enthusiasts. Our chocolate-and-blue colours could be seen everywhere in the morning, especially along the Strand and all the principal thoroughfares. At half-past two there was a general stampede towards Kennington Oval and cabs, cars, carriages, traps and a thick line of pedestrians could be seen moving down the road. Arriving on the ground, it was at once manifest how great an interest the encounter had awakened. There was a dense multitude of from fifteen to twenty thousand, many familiar faces being among the number. At the last moment,5-to-4 on the Albion could be obtained and the betting in their favour was very brisk.

A few minutes before three we entered the field and were greeted with a hearty round of cheering. I had given the Villa team special instructions how to play this match; briefly they were these - every man was to stick to his position and look after the opponent he was facing. This, of course, does not give such opportunities of brilliant play, but it is a measure of safety which I strongly commend. Let every player single out his man and determine to beat him and if he is equal to the effort the game is won. This course demands an amount of unselfishness on the part of the players which is very hard to exercise, but I have so often seen brilliance and danger combined that on such an occasion as the one I speak of we could not afford to run any such risk. Consequently the match from beginning to end was less scientific than the match with the Rangers. In this respect it was doubtless disappointing. But as a hard, fierce struggle it is not to be surpassed.

Bayliss won the toss and I kicked off exactly at half-past three. As I did so a subdued hum of excitement could be heard and we knew that everybody's nerves were strung to the utmost. I don't know whether I am equal to describing all the details of the match. So far as play went I was coot enough, but so intent upon the game that when it was all over I could only remember a confused multitude of incidents in no particular order, but all warm, vigorous and exciting. I remember how we scampered up and down the field, what wild rushes were made, how the ball bounded here and there, the desperate charges that followed, the frenzied scrimmages, the impulsive shooting, the grand work of the goalkeepers, the attack and defence, the dangers and the relief, the terrific and prolonged struggle and yet, up to half-time, not a single goal! I recall with a thrill how we saw at one point that the Albion were getting the better of us and how we saw them with dismay closing round our citadel. Then how exhilarating it was to see the danger past, to know that the attack had been unavailing and to find ourselves racing away with the ball towards the opposite goal. How often Warner and Roberts saved I cannot tell. Time after time the shots went in scorching hot and always the men between the timbers were equal to the emergency and this was why when half the game was over there was no score.

Changing ends, the Albion cut out the work and Hodgetts and Vaughton on our side commenced putting in an immense amount of good work. A determined attack by them was repelled by Tom Green, who got away up the field and was stopped by Coulton, who returned. From this kick Davis with a long shot centred to Hodgetts, who was close in goal and he with consummate ease, put the ball through, completely baffling Roberts. Then what a cheer arose! The Villa had scored and the jubilation of our supporters was boundless. By the time they had settled down again we were in the midst of a fast and dashing game. It seemed, however, as if no further points would be gained. Both sides were playing desperately and every man was working as if his life depended upon the victory. We were constantly in front of goal and a foul being given to the Albion there, matters looked dangerous. But it was only at the end of the game that the finishing stroke was to be given to our victory. I got possession of the ball and eluding the backs got right in front; but the ball was going at such a furious pace that I perceived I could not reach it. Roberts saw reach the ball and give it the necessary push. If I had not adopted this expedient I could not possibly have scored. The cheers had scarcely subsided when the whistle blew and the Villa had won the Cup by two goals to none.

Major Marindin, President of the Football Association, who acted as referee, was good enough to say that the match was not won be science but "by Archie Hunter's captaincy." As soon as the whistle blew I was surrounded by the enthusiastic crowd and for a few moments I thought I should be torn in pieces. They nearly wrung my hand off and those who could not get near enough put all the heart they could into shouting "Bravo, Archie" and "Well done, Villa." Finally, I was lifted shoulder-high and amid the wildest demonstrations carried all round the field, nor would my zealous friends release me until the moment came when I was called upon to receive the Cup.

(6) Ernest Needham, Association Football (1901)

Another great forward who plays the same game as Spikesley and Athersmith is Bassett, of West Bromwich. Bassett is getting a little stale, but in his day he was, without doubt, the best outside right in the British Isles. Many of my readers will have seen him play, for it is well known that a great many spectators went to see Bassett, and Bassett alone. Athersmith's name has been coupled with his; but whilst one is in his prime, the other is going back; at all events, they are both of International calibre.

(7) Gavin McOwan, The Essential History of West Bromwich Albion (2002)

The Albion side of the mid-1880s was a good one, but there was still one piece of the jigsaw missing. At the back Charlie Perry had become a masterful centre half, the coolest of customers under pressure who, having made his full team debut in the 1886 final, was already a fine captain of the side a year later. In attack the side possessed able goalscorers in the form of Bayliss and Woodhall, and in goal Bob Roberts was still one of the best keepers in the Country.

But it was the arrival of one William Isaiah Bassett at the start of the 1887-88 season that made this side a great one, perhaps the best in the country at that time, and finally enabled them to bring the FA Cup back to West Bromwich. Standing just five feet, five inches tall, Bassett was born in the town and had played for various local clubs before joining Albion in 1886. At first it was thought that he was too lightweight to become a successful professional, but When Aston Villa poached Albion's inside right, Tom Green, Bassett took his chance, making his full debut against Wednesbury Old Athletic in the glorious Cup campaign of 1887-88. The combination of the peerless Bassett and George Woodhall on the right wing, along with Jem Bayliss at centre forward, was prolific, and that season Albion hit a tally of 195 goals in 58 first-team matches. Prolific, that is, once the more experienced Woodhall had ended his childish behaviour of refusing to pass to the young pretender, who was already laying claim to his position as tile club's star player...

Bassett was the inspiration for Albion's first Cup final win, making both goals in the 2-1 will on what was an eventful weekend for both him and the club. The young winger had played so well that after the game he was selected to play for England.

(8) J. A. H. Catton, The Story of Association Football (1926)

I will jump to 1892 when Arthur Dunn led on to the field at Ibrox an eleven which were supposed to be ready prey for the Scots even if they had to recall Wattie Arnott, who was then not only beyond his prime but short of practice and training. This English team was called "The Old Crocks." I suppose that was because Arthur Dunn, the Old Etonian, who was one of the two centre forwards against Ireland in 1884, was at last re-called, and came in as a full-back, if you please.

"The Old Crocks" consisted of George Toone, of Notts County, in goal, Arthur Dunn and "Bob" Holmes, of Preston, as backs, John Reynolds (then of West Bromwich), Johnny Holt, that "little devil of Everton" as Sam Widdowson called him, Alfred Shelton (Notts County) as halfbacks, with "Billy" Bassett and Johnnie Goodall on the right wing, Jack Southworth ("Skimmy") in the centre, and Edgar Chadwick and Dennis Hodgetts on the left wing. Why did the Scotsmen and the critics call this lot "the Old Crocks"? The Scottish journalists labelled them in this manner, and the triumph of Scotland was assured.

The evening before the match the players of both teams fraternised. They were not kept in separate camps, or hotels, in those days. Oh yes, these Scotsmen openly boasted what they were going to do with these English "veterans" (vide Bassett, then about twenty-three years of age).

Their confidence was boundless. Sandy McMahon was going to sand-dance round Johnny Holt, carry the ball on his head from the half-way line, and pop it into goal, and do all sorts of wonderful juggling. William Sellar was to score again and again, and Kelly of the Celts, was to put Southworth in his pocket and button it up.

What did Bobby Burns say about the best laid schemes of mice and men? That "little devil" Johnny Holt was "all over" McMahon; he climbed up him and over him, brought him down to earth and sand-danced on him.

For twenty minutes the Scots never touched the ball, and in seventeen minutes the "old crocks" of England had scored four goals, so completely outwitted were Kelly, Dan Doyle, and Wattie Arnott.

Within ten seconds England had scored. John Southworth kicked off, and Goodall tipped the ball to Bassett, who swung a pass towards the left, Chadwick gained possession, dribbled round Arnott, and drove past McLeod, of Dumbarton, the goalkeeper. The trick was done and the Scots had never played the ball.

The "Old Crocks" gave a display such as I have never seen-either before or since. That was not the only goal which was perfect in conception, combination, and execution.

This was a far more wonderful exhibition of the game than that of the following year at Richmond, when England won by 5-2. The Surrey Cricket Club felt compelled to refuse the use of The Oval as part of the cricket ground had been re-laid, and the match was taken to an athletic ground at Richmond, which was well known as a Rugby rendezvous. The match furnished a splendid "gate."

But it also furnished what is far more important-a splendid match. The issue was in doubt in the second half, and I thought that the Scots would win. As a rule, my interest in the issue of a match is negligible, but I do like to see England triumph in this great match. The feeling is only natural in an Englishman.

The match was, however, won by rare combination and enviable endurance. The unity of the team was not really developed until after the interval, when Bassett cross-kicked to the left wing again and again, and Spiksley (by the way, he writes his name without an "e" in the centre) scored three goals in succession in about ten minutes! I cannot remember any other Englishman performing "the hat trick" against Scotland. These goals were brilliants.

The Scots protested on the ground of off-side to the referee, who I think was Mr. J.C. Clegg, but he was against them every time. It seemed to me that the Caledonians were not allowing for the speed of Spiksley, who was much faster than he looked, and a player worthy to rank with Mosforth, Hodgetts, or any other outside-left.

Spiksley's control of the ball, his individuality, and his pluck for a man of modest stature, without much weight, were amazing. Like Hodgetts, Fred Spiksley did his ball work with the outside of the right foot. In fact, Fred Spiksley could do almost anything he wanted with either foot, and was a sure marksman. Spiksley as a football player was a wonder.

(9) Frederick Wall, 50 Years of Football (1935)

The Football Association have spared no effort to encourage and develop the playing of the game. The first official team sent over the English Channel went to Berlin in 1899. I did not go, but when the players returned, no tale caused so much merriment as the experience of William Bassett on the Tempelhofer Field. A halfback was told never to leave Herr Bassett, to be with him wherever he went. Bassett soon discovered these instructions, and just to see if he was right, he went off the playing area, ran behind one of the goals and re-entered the arena on the other side of the net. The half-back went with him and never left him. Naturally Bassett, now the chairman of West Bromwich Albion, laughed and led his close companion many a merry dance.