Wolverhampton Wanderers : 1877-1918

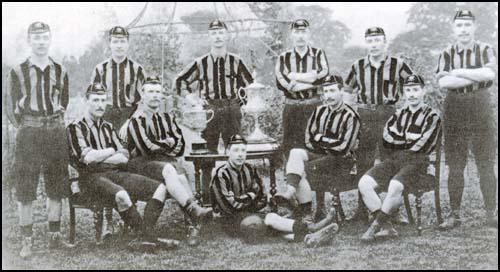

Wolverhampton Wanderers were formed in 1877 by John Baynton and John Brodie. The team was made up of former students at St Luke's school in Blakenhall. On two occasions they reached the final of the Birmingham Cup, only to lose to Wednesbury Old Athletic. Wolves won their first cup in 1884 when they defeated Hadley in the final of the Wrekin Trophy by 15-0.

Wolverhampton Wanders entered the Football Association Challenge Cup for the first-time in the 1886-87 season. However, they were knocked out in the 3rd round by Aston Villa.

The decision to pay players increased club's wage bills. It was therefore necessary to arrange more matches that could be played in front of large crowds. On 2nd March, 1888, William McGregorcirculated a letter to Aston Villa, Blackburn Rovers, Bolton Wanderers, Preston North End, and West Bromwich Albion suggesting that "ten or twelve of the most prominent clubs in England combine to arrange home and away fixtures each season."

J. J. Bentley of Bolton Wanderers and Tom Mitchell of Blackburn Rovers responded very positively to the suggestion. They suggested that other clubs should be invited to the meeting being held on 23rd March, 1888. This included Accrington, Burnley, Derby County, Notts County, Stoke, Wolverhampton Wanderers, Old Carthusians, and Everton should be invited to the meeting.

The following month the Football League was formed. It consisted of six clubs from Lancashire (Preston North End, Accrington, Blackburn Rovers, Burnley, Bolton Wanderers and Everton) and six from the Midlands (Aston Villa, Derby County, Notts County, Stoke, West Bromwich Albion and Wolverhampton Wanderers). The main reason Sunderland was excluded was because the other clubs in the league objected to the costs of travelling to the North-East. McGregor also wanted to restrict the league to twelve clubs. Therefore, the applications of Sheffield Wednesday, Nottingham Forest, Darwen and Bootle were rejected.

The first season of the Football League began in September, 1888. Preston North End won the first championship that year without losing a single match and acquired the name the "Invincibles". Eighteen wins and four draws gave them a 11 point lead at the top of the table. Wolves finished in third place with 28 points. Wolves had a great defensive record with half-backs, Alfred Fletcher, Arthur Lowder and Harry Allen representing England in the 1889 international games.

Wolves did even better in the FA Cup. They beat Old Carthusians (4-3), Walsall Town Swifts (6-1), Sheffield Wednesday (5-0) and Blackburn Rovers (3-1). Preston beat Preston North End 3-0 in the final. The goals were scored by Jimmy Ross, Fred Dewhurst and Samuel Thompson. Preston won the competition without conceding a single goal.

Wolves continued to do well finishing in 4th (1889-90), 4th (1890-91) and 6th (1891-92). Wolves finished a disappointing 11th in 1892-93 but had a very successful cup run beating Bolton Wanderers (2-1), Middlesbrough (2-1), Darwen (5-0) and Blackburn Rovers (2-1).

Wolves played Everton at the Fallowfield Ground in Manchester in the 1893 FA Cup Final. Nine of the Wolves team were locally born players. Everton on the other hand fielded six players from Scotland. Over 40,000 people turned up to see the game. Wolves won the game with the only goal scored by Harry Allen.

Wolves finished in bottom place in the 1905-06 season and the club was relegated to the Second Division. The club failed to win promotion in 1906-07 (6th) and 1907-08 (9th). They did enjoy a good run in the FA Cup in 1908. They beat Bury (2-0), Swindon Town (2-0), Stoke City (1-0) and Southampton (2-0) to reach the final against Newcastle United. Newcastle had just finished 4th in the First Division during this season, and after two successive league titles they were hot favourites to win the cup against their Second Division opponents. It was also Newcastle's third FA Cup final appearance in 4 years.

Newcastle United had the vast majority of the possession but couldn't penetrate the Wolves defence. After 40 minutes a poor clearance went straight to Kenneth Hunt, the Wolves right-half. Jim Lawrence, the Newcastle goalkeeper, got a hand the Hunt's tremendous shot but could not keep it out of the net. Soon afterwards George Hedley scored a second. In the second-half, Newcastle's constant pressure resulted in a goal for Jimmy Howie. Just before the end, Wolves broke away and Billy Harrison added a third.

Despite their good FA Cup form Wolves found it impossible to get out of the Second Division finishing in 7th (1908-09), 8th (1909-10), 9th (1910-11), 5th (1911-12), 10th (1912-13), 9th (1913-14) and 4th (1914-15). After the First World War Wolves continued to struggle: 19th (1919-20), 15th (1920-21) and 17th (1921-22). The following season they finished last and the club was relegated to the Third Division.

William Caddick, Wolves' centre-half, was appointed as captain. The club won the Third Division North championship in the 1923-24 season. In the 1924-25 season Wolves finished 6th in the 1924-25 season. The following year it was 4th but after slipping to 15th, the club decided to appoint Major Frank Buckley as manager. As Patrick A. Quirke, the author of The Major: The Life and Times of Frank Buckley pointed out: "His experience at both Blackpool and Norwich of acquiring skilled and talented players at little or no cost and then selling them on at a healthy profit was extremely appealing to those concerned with club finances."

As at Blackpool he introduced a new football strip. He designed the shirts himself. They were deep gold with black trimmings. He also brought in new training methods he had used at Blackpool. This included exercises with Indian clubs and weight training.

Frank Buckley gave each of his players a small pocket book in which was printed details of the conduct he expected from them. As well as advice on not smoking, he insisted that they did not go out socialising for a least two days prior to a match. Buckley also informed the Wolverhampton public of these regulations and asked them to contact him if they saw a player breaking the rules.

Over the years Buckley had built up a network of football scouts who attempted to discover talented young players. In 1927 he purchased Dai Richards from Merthyr Town. This was followed by Reg Hollingsworth, a centre-half from Sutton Junction, Billy Barraclough from Hull City, Billy Hartill a centre-forward who was playing for the Royal Horse Artillery and Charlie Phillips from Ebbw Vale.

Noel George, the club goalkeeper, was diagnosed as being terminally ill with a disease of the gums and died in 1929. He had played in 292 games for Wolves. Buckley was convinced that George's death was due to ill-fitting dentures. From that time on he made sure that all his players who wore dentures were examined by a dentist every six months.

Wolves lost to lowly Mansfield Town 1-0 in the FA Cup in 1929. Frank Buckley was so upset with the performance of his players that he organized a training-run through Wolverhampton town centre for the first-team players on a market-day during the following week.

In 1929 Frank Buckley signed Mark Crook, a talented winger from Blackpool. That season Billy Hartill scored 33 goals in 36 games. This included all five against Notts County at Molineaux. Despite these goals Wolves could only finish in 9th place in the league.

The following season Wolves finished 4th in the Second Division. Billy Hartill was again top scorer with 30 goals in 39 appearances. Major Frank Buckley added Tom Smalley for his first-team squad in 1931. He was a coalminer who had been playing his football for South Kirkby Colliery. Smalley was to develop into an important member of the team. He also signed Gordon Clayton, a young centre-forward from Shotton Colliery.

Billy Hartill scored 30 goals with hat-tricks against Plymouth Argyle, Bristol City, Southampton and Oldham Athletic, in the 1931-32 season and helped the club win the Second Division championship. Charlie Phillips was also in great form adding 18. The club scored 118 goals that season.

The championship winning team that season included only one player that had not been signed by Frank Buckley. The Wolverhampton Express and Star report on the success included the following tribute: "By his splendid work with the Wolves he has built up a reputation as a football manager second to none in the country... At the Molineux Ground he has proved himself a splendid judge of a player. His ability to find a young talent is unequalled and despite the handicaps with which he is faced when joining the club he has discovered a whole team, which has taken Wolves into the highest flight."

In August, 1933, Frank Buckley purchased Bryn Jones from Aberaman for a fee of £1,500. In his first season at Wolves he scored 10 goals in 27 appearances. Although very popular with the fans, Jones was unable to immediately turn Wolves into a successful side.

Billy Hartill remained in good form scoring 33 goals. This included four against Huddersfield Town and hat-tricks against Blackburn Rovers and Derby County. In the 1933-34 season they finished in 15th place in the First Division. However, crowd attendances had doubled and the board declared profits of £7,610.

Stan Cullisjoined Wolves in 1934. Cullis later recalled: "Major Buckley, apparently, decided very quickly that I might make a captain." When Cullis was only 18 years old and in the "A" team he was told by Buckley: "Cullis, if you listen and do as you are told, I will make you captain of Wolves one day."

1934 also saw the arrival of Jimmy Utterson, a goalkeeper from Glenavon in the Irish League. Unfortunately, he only played in 12 games before he died from head injuries he had received in a game against Middlesbrough.

Major Frank Buckley continued to search for new talent and in 1934 he signed Billy Wrigglesworth, a winger from Chesterfield, David Martin from Belfast Celtic and Tom Galley, a midfielder, from Notts County. In the 1934-35 season Wolves finished in 17th place in the First Division winning only 15 of their 42 games. Billy Hartill was again top scorer with 33 goals.

In 1935 Buckley signed Alex Scott, a goalkeeper, for a fee of £1,250 from Burnley. However, he upset the Wolves' fans by selling Billy Hartill to Everton. A few months later he sold Charlie Phillips to Aston Villa for £9,000. It seemed that Buckley and the Wolves board were more concerned with making a profit than winning the First Division championship. Wolves again struggled in the 1935-36 season finishing in 15th place, only five points above the relegated teams, Aston Villa and Blackburn Rovers.

Wolves started the 1936-37 season badly. They won only four games out of their first 14 and after a 2-1 defeat at home to Chelsea the crowd invaded the pitch from the South Bank and called for the resignation of Major Frank Buckley. The crowd uprooted the goalposts before police reinforcements restored order. Buckley was offered police protection but he refused and walked home alone. Newspaper reports suggest that over 2,000 people were involved in the demonstration against Buckley.

Buckley later recalled that the main cause of this hostility was his policy of selling established players in order to balance the books. However, he argued this enabled him to play, younger, more talented players who became known as the "Buckley Babes".

In January 1937, Frank Buckley again upset the Wolves' fans by selling Billy Wrigglesworth to Manchester United, who had the very good record for a winger, scoring 21 goals in 50 games for the club. However, Wolves had a good run in the league after Christmas and eventually finished in 5th place behind champions Manchester City.

At the beginning of the next season Buckley appointed Stan Cullis as captain of Wolves in 1937. In his autobiography, All for the Wolves (1960), Cullis claimed: "Buckley spent many hours drilling me in the precious art of captaincy, telling me in no ambiguous terms that I was to be the boss on the field. No youngster of eighteen could ask for a better instructor than the major, who laid the foundations of the modern Wolves during his sixteen years at Molineux".

Patrick A. Quirke, the author of The Major: The Life and Times of Frank Buckley argues that Buckley developed a unique style of management: "At whichever club he was at, to his players Major Buckley was not only their manager; he was their coach and trainer.... Buckley used training methods that might now be seen as crude forms of psychological behaviour modification."

For example, Gordon Clayton, the Wolves centre-forward, went through a barren period when he was unable to score. He got barracked by the Molineux crowd so badly that he considered giving up the game. Major Frank Buckley considered him a "grand centre-forward" and argued that it would be a "football tragedy" if this happened. Buckley's wife suggested that Clayton should have a "course of psychology" with a local doctor. This was a great success and Clayton went on to score 14 goals in the next 15 matches.

After finishing the course of treatment Gordon Clayton wrote to Dorothy Buckley: "I just learnt that it was you who was actually responsible for my treatment. I am very pleased with my success so far and I know you will be equally pleased. I cannot really thank you enough for what you have done... As you no doubt know the very name of Wolverhampton Wanderers was a nightmare to me. I detested the place. I do not think I was liked or respected by a single person with the exception of Major Buckley, who I have no doubt was always interested in my welfare, even though I must have exasperated him often."

Frank Buckley did not like the idea of football players being married. He thought that wives might "get in the way" of players concentrating on developing their skills. He also thought that a wife's anxiety about her husband's safety might affect him and his performance. Buckley had forty players in his 1937 squad and all were bachelors.

In the 1930s football teams travelled to away grounds on the day of the match. Buckley observed that players often arrived tired and fatigued. He therefore arranged for players to stay overnight in hotels when playing distant away fixtures. Buckley even argued "that where possible players should be ferried to games by air" and predicted that in future every top club would have its own helicopter to do this.

Major Frank Buckley developed a more direct style of playing football. "It was simply the task of the defenders to get the ball forward as quickly as possible and not to over-elaborate their roles. The wingers were to take opposition defenders on and cross the ball to the central attackers whose job it was to put the ball in the net... He wanted fewer dribbling moves and more passing." Stan Cullis said that players were expected to do exactly as Major Buckley ordered otherwise "you'd very soon be on your bicycle to another club."

Major Frank Buckley wanted to take his team on a tour of Europe before the start of the 1937-38 season. However, the Football Association refused permission for this to go-ahead due to "the numerous reports of misconduct by players of the Wolverhampton Wanderers Club during the past two seasons." There had been seven sendings-off while Buckley was manager of the club. However, as Buckley pointed out, four of these were accounted for by two players, Charlie Phillips and Alex Scott.

Stan Cullis and his teammates wrote to the FA claiming: "We would like to state that far from advocating the rough play we are accused of, Major Buckley is constantly reminding us of the importance of playing good, clean and honest football, and we as a team consider you have been most unjust in administering this caution to our manager."

In the summer of 1937 Frank Buckley was approached by a chemist called Menzies Sharp. He claimed he had a "secret remedy that would give the players confidence". It is believed that Sharp's ideas were based on the experiments of Serge Voronoff, a French doctor, who had been born in Russia. Between 1917 and 1926, Voronoff carried out over five hundred transplantations on sheep and goats, and also on a bull, grafting testicles from younger animals to older ones. Voronoff's observations indicated that the transplantations caused the older animals to regain the vigor of younger animals.

Sharp's "gland treatment" involved a course of twelve injections. Frank Buckley later explained: "To be honest, I was rather sceptical about this treatment and thought it best to try it out on myself first. The treatment lasted three or four months. Long before it was over I felt so much benefit that I asked the players if they would be willing to undergo it and that is how the gland treatment became general at Molineux."

Two Wolves players, Dicky Dorsett and Don Bilton, refused to undergo the "gland treatment". According to Patrick A. Quirke, the author of The Major: The Life and Times of Frank Buckley (2007): "Dorsett, a well-established and experienced footballer, had stood up to Major Buckley's insistence (some might say bullying) on a number of occasions."

Don Bilton recalls that he was signed by Major Buckley from York City. On his arrival at the club he was instructed by Buckley to report to the medical room for gland injections. Bilton replied: "I'm sorry Sir, but I am only seventeen and still under my father's guidance. He will not want me to have injections." Buckley told him that he was under contract and had to do as he was told. Bilton's father went to see Buckley the following day and after a heated row the manager backed-down. However, Bilton claimed that: "Buckley was not at all pleased by this and I never did much good at Wolves after that!"

Rumours circulated that Wolves players were being injected with "gland extracts from animals". Tommy Lawton, who was a member of the Everton team that lost 7-0 to Wolves, believed that these injections were improving the performance of the players. He claimed that before the game he tried to speak to Stan Cullis but "he walked past me with glazed eyes".

On 9th April, 1938, Dicky Dorsett and Dennis Westcott both scored four goals when Wolves beat Leicester City 10-1. After this defeat the club complained to Montague Lyons, the Leicester member of the House of Commons that the Wolves players were being injected with monkey glands. Lyons demanded that the government instigate an investigation into this treatment. When Walter Elliot, the Minister of Health, rejected this request, Emanuel Shinwell, the Labour MP, suggested that considering Wolves' impressive form, ministers of the Conservative government should be put on a course of these injections.

The Football League carried out an investigation into the "monkey gland" treatment. However, it refused to ban these injections but they did arrange for a circular to be posted in the dressing rooms of every club in England and Wales. This declared that players could take monkey glands but only on a voluntary basis.

Major Frank Buckley was gradually building up a very good squad that included Stan Cullis, Gordon Clayton, Bill Morris, Dennis Westcott, George Ashall, Alex Scott, Jack Taylor, Tom Galley, Dicky Dorsett, Bill Parker, Bryn Jones, Joe Gardiner and Teddy Maguire.

Buckley sold Gordon Clayton to Aston Villa in October 1937. Dennis Westcott replaced Clayton as centre-forward and scored his first hat-trick against Swansea City. In the 1937-38 season Wolves finished second to the mighty Arsenal in the First Division. Westcott finished the season as top scorer with 22 goals in 28 appearances.

At the time, Arsenal dominated the First Division championship, having won it four times in six years. Alex James, their creative inside-forward, had recently retired. The club was looking for a replacement and Buckley decided to sell his star player, Bryn Jones for the world record fee of £14,000 (£6.9 million in today's money). Politicians were outraged by the money spent on Jones and the subject was debated in the House of Commons. Buckley later recalled that people would spit at him and his wife as they walked around Wolverhampton after he sold Jones.

As Stan Cullis pointed out: "Throughout the middle years of the 1930s, Major Buckley steadily built up the team he believed would capture most of the honours in England. From the large numbers of lads he brought to Molineux for trials, he signed enough professionals both to form his team and to bring in a fortune from the transfer market. At a time when a five-figure transfer fee still astounded the football public, Major Buckley earned £130,000 for Wolves in five years before the 1939-45 war. This spell established Wolves as one of the wealthiest football clubs in Britain."

In 1938 Major Frank Buckley agreed a new ten-year contract with Wolves. He told the local newspaper: "Since coming to Wolverhampton ten years ago I have become so bitten by the Wanderers bug that no other club could ever interest me. It has been a pleasure to work in the town and, while we have had our differences, they have been plainly stated. I shall be happy to spend my football life with the club I so love."

George Ashall, Alex Scott, Jack Taylor, Tom Galley. Front row:Dicky Dorsett,

Bill Parker, Bryn Jones, Joe Gardiner andTeddy Maguire

In the 1938-39 season Wolves finished second to Everton. The centre-forward Dennis Westcott scored 43 goals in 43 appearances. His fellow striker, Dicky Dorsett managed 26 goals that season. The captain of the side, Stan Cullis, was generally acknowledged as the best centre-half in the Football League. That season also saw the arrival of teenagers, Billy Wright, Joe Rooney and Jimmy Mullen, in the side.

Wolves also enjoyed a good run in the FA Cup and beat Leicester City (5-1), Liverpool (4-1), Everton (2-0), Grimsby Town (5-0) to reach the final against Portsmouth at Wembley. Wolves lost the final 4-1 with Dicky Dorsett scoring their only goal. Major Buckley's Wolves became the first team in the history of English football to be runners-up in the sport's two major competitions in the same year. Afterwards, it was discovered that the Portsmouth players, like those of Wolves, had also been injected with monkey glands.

The outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 brought an end to the Football League. Major Frank Buckley attempted to re-join the British Army but at the age of 56 he was considered too old. However, he did encourage all his players to join and according to the Football Association publication, Victory Was The Goal (1945), between 3 September 1939 and the end of the war, 91 men joined the armed forces from the club.

In 1940 Major Frank Buckley took command of a Home Guard unit in Wolverhampton. Buckley held nightly meetings at the local Territorial Army Hall that was situated near his home at St Jude's Court. According to Patrick A. Quirke, the author of The Major: The Life and Times of Frank Buckley: "Being totally dedicated to individual physical fitness, Major Buckley would often march his men to the Molineux where they would use the club's exercising facilities and the pitch itself as a training ground."

The government imposed a fifty mile travelling limit on all football teams and the Football League divided all the clubs into seven regional areas where games could take place. Wolves joined the Midland League with West Bromwich Albion, Birmingham City, Coventry City, Luton Town, Northampton Town, Leicester City and Walsall. Wolves won the 1939-40 championship. Top scorers were Dennis Westcott (26), Dicky Dorsett (16) Jimmy Mullen (7) and Billy Wright (5).

Wolves also reached the final of the Football League War Cup. The team included Eric Robinson, Tom Galley, Dicky Dorsett, Jack Taylor, Frank Broome, Dennis Westcott, Jack Rowley and Jimmy Mullen. Wolves drew 2-2 with Sunderland in the first leg but won the second game 4-1 with goals from Rowley (2) Westcott and Broome.

Sergeant Eric Robinson tragically drowned on 20th September 1942 while taking part in military exercises in the River Derwent. Joe Rooney was killed in action in 1943. Bill Shorthouse was badly wounded during the D-Day landings but survived to play for Wolves after the war.

Frank Buckley retained his belief in youth and in September 1942 he gave a debut to Cameron Buchanan. At the age of fourteen years and fifty-seven days he was probably the youngest teenager to play for a Football League club. He played in a further 11 games before joining Bournemouth before the end of the war. Buckley also played Emilo Aldecoa, a political refugee who had been forced out of his own country by the Spanish Civil War.

Frank Buckley resigned as manager of Wolves on 8th February 1944. This shocked the directors as they had given him a ten-year contract in 1938. During his 18 years at the helm, Buckley made £100,000 for Wolves in transfer dealings. The following month he joined Notts County in the Third Division on the extraordinary wage of £4,500 a year.

After receiving over a hundred applications the board appinted Ted Vizard as the new manager. Wolves finished 3rd behind Liverpool in the 1946-47 season. Dennis Westcott scored an amazing 38 league goals in only 35 games, a club record. Other regular scorers included Jesse Pye (20), Jimmy Mullen (11) and Johnny Hancocks (10).

The following season Dennis Westcott suffered from a series of injuries but still scored 11 goals in 22 games before Ted Vizard surprisingly sold him to Blackburn Rovers in April 1948. Wolves finished in 5th place. Top scorers that season were Jesse Pye (16) Johnny Hancocks (16) Jimmy Dunn (9) and Jimmy Mullen (8).

Ted Vizard was replaced by his assistant Stan Cullis in June 1948. Cullis insisted that his team should play at a higher tempo than the opposition. He believed that this would pressure them into making mistakes during the game. For this strategy to work, the Wolves players had to be fitter than other clubs. Cullis introduced a new training regime that involved tackling commando-like assault courses. Each player was given specific targets. Minimum times were set for 100 yards, 220 yards, 440 yards, 880 yards, 1 mile and 3 miles. All the players had to be able to jump a height of 4 feet 9 inches. Cullis gave his players 18 months to reach these targets.

Wolves finished in 6th place in the 1948-49 season. Top scorers were Jesse Pye (17), Sammy Smythe (16), Johnny Hancocks (12), Jimmy Mullen (12) and Dennis Wilshaw (10).

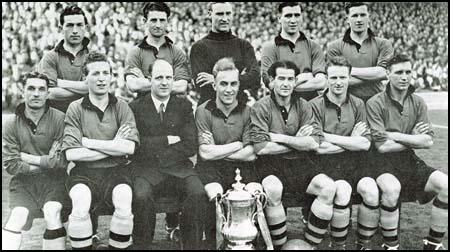

The club also had a good run in the FA Cup beating Sheffield United (3-0), Liverpool (3-1), West Bromwich Albion (1-0) and Manchester United (1-0) to reach the final against Leicester City. The team for the final included Johnny Hancocks, Sammy Smyth, Jesse Pye, Jimmy Dunn, Jimmy Mullen, Billy Crook, Roy Pritchard, Billy Wright, Bert Williams, Bill Shorthouse and Terry Springthorpe. Wolves won the game 3-1 with Pye scoring two goals in the first-half and Smythe netting a third in the 68th minute.

Back row (left to right): Billy Crook, Roy Pritchard, Bert Williams, Bill Shorthouse,

Terry Springthorpe. Front row: Johnny Hancocks, Sammy Smyth, Stan Cullis,

Jesse Pye, Jimmy Dunn and Jimmy Mullen.

In the 1949-50 season Roy Swinbourne emerged as a very promising player. As Stan Cullis pointed out in his autobiography, All For the Wolves: "Tall and strong, Swinbourne could gain possession of the ball on the ground and, in the air, he could beat most defenders. As he learned, and removed the rough edges from his game, he developed into a first-class centre-forward for Wolves" That season Wolves finished in second place to Portsmouth. Top scorer was Jesse Pye with 18 goals. However, Swinbourne who came into the side after Christmas, managed to score seven goals.

In May 1950, Stan Cullis signed Peter Broadbent from Brentford for a fee of £10,000. As Cullis later pointed out: "The club paid a big fee to Brentford for the transfer of Peter Broadbent, a 17-year-old inside-forward from Dover, who, I thought, could well develop into one of the outstanding inside-forwards of his day. Broadbent, in addition to the normal qualities of an inside-forward, also had considerable pace, and a flair for going past a defender in the fashion of a winger."

Peter Broadbent made his debut against Portsmouth in March 1951. He joined a team that included Johnny Hancocks, Sammy Smyth, Jesse Pye, Jimmy Dunn, Dennis Wilshaw, Jimmy Mullen, Billy Crook, Roy Swinbourne, Roy Pritchard, Billy Wright, Bert Williams, Bill Shorthouse and Terry Springthorpe. Wolves only finished in 14th place in the First Division in the 1950-51. The top goalscorers were Swinbourne (20) and Hancocks (19).

In the 1952-53 season Wolves finished in 3rd place in the First Division. Peter Broadbent formed a great partnership with Johnny Hancocks. As the manager, Stan Cullis, pointed out in his autobiography, All For the Wolves (1960): "We often used him (Broadbent) as an advanced winger lying on the touchline twenty yards or more ahead of Hancocks. When the ball came out of defence to Hancocks, he was able to chip it accurately to Broadbent who was frequently clear on his own. This stratagem, designed to make the fullest use of the best qualities of both players, was also extremely successful, for the full-back marking Hancocks was caught between two men and played out of the game." That season the top goalscorers were Roy Swinbourne (21), Dennis Wilshaw (17), Jimmy Mullen (11) and Johnny Hancocks (10).

Wolves won the First Division championship in the 1953-54 season with four more points than their nearest challenger, West Bromwich Albion. They scored an impressive 96 goals. The top goalscorers were Johnny Hancocks (25), Dennis Wilshaw (25), Roy Swinbourne (24), Jimmy Mullen (17) and Peter Broadbent (12). Wilshaw did not enjoy a good relationship with Stan Cullis. However, he claimed that the club's team spirit was good "because we all hated his guts".

In the 1954-55 season lost the services of Roy Swinbourne who was injured early in the season. Despite the goals of Johnny Hancocks (26) and Dennis Wilshaw (20) Wolves could only finish second to Chelsea. Swinbourne also struggled with injuries the following season and once again could only play in 14 league games. His place in the side was taken by Jimmy Murray who scored 11 goals that season. Wolves finished in 3rd place that season.

Roy Swinbourne was forced into retirement at the end of the 1955-56 season. As Stan Cullis pointed out "although he tried for nearly two years to find his old speed, Swinbourne never recovered from that accident and... football lost a potentially great centre-forward."

In March 1956 Stan Cullis signed Harry Hooper from West Ham United for a club record fee of £25,000. Cullis wanted him as a replacement for Johnny Hancocks. Cullis later commented that: "Like Hancocks, Hooper was fast, direct, able to play on either wing and was both accurate and powerful in his use of the ball with either foot. In short, he was an ideal winger."

Harry Hooper joined a team that included Peter Broadbent, Eddie Clamp, Ron Flowers, Johnny Hancocks, Jimmy Mullen, Roy Pritchard, Bill Shorthouse, Bill Slater, Roy Swinbourne, Dennis Wilshaw, Billy Wright, Bert Williams, Eddie Clamp, Norman Deeley, Eddie Stuart, Jimmy Murray and Bobby Mason.

In the opening game of the 1956-57 season, Jimmy Murray scored 4 goals in a 5-1 defeat of Manchester City and ended the season with 17 goals in 33 games. However, it was Harry Hooper who ended up as top scorer with 19 goals in 39 games.

In 1957 Norman Deeley replaced Harry Hooper on the right-wing. Cullis argued that: "At Molineux, Hooper found it extremely difficult to adapt himself to our style. He played several outstanding games for us but there was no doubt that he did not carry out our tactical principles to the extent I considered was essential." Deeley joined a forward-line that included Jimmy Mullen, Jimmy Murray, Peter Broadbent and Bobby Mason. As Ivan Ponting pointed out: "He compensated amply in skill, determination and bravery for what he lacked in physical stature."

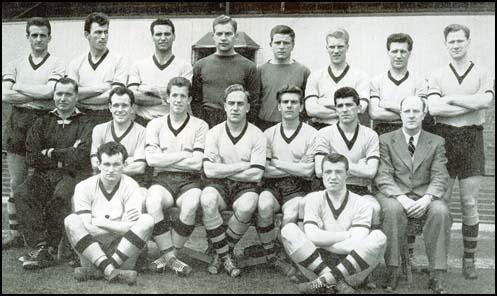

back row: Jerry Harris, Eddie Clamp, Eddie Stuart, Malcolm Finlayson, Noel Dwyer,

Ron Flowers, Jimmy Mullen and Bill Slater. Middle row: Joe Gardiner (trainer),

Norman Deeley, Peter Broadbent, Billy Wright, Bobby Mason, Colin Booth and

Stan Cullis (manager). Front row: Jimmy Murray and George Showell.

Wolves won the League Championship in 1957-58 by 5 points from Preston North End. The club scored an amazing 103 league goals that season. Jimmy Murray was the club's leading scorer with 32 goals in 45 games. This included hat-tricks against Birmingham City (5-1) Nottingham Forest (4-1) and Darlington in the FA Cup ( 6-1). Norman Deeley scored 23 goals in 41 appearances that season. This included a spell of 13 in 15 outings during the autumn. Other scorers included Peter Broadbent (17), Eddie Clamp (10), Bobby Mason (7), Dennis Wilshaw (4), Jimmy Mullen (4), Des Horne (3) and Ron Flowers (3).

Wolves also won the title in the 1958-59 season with 28 wins in 42 games. Once again the forwards were in great form scoring 110 goals. This was seven more than Manchester United and 22 more than third placed Arsenal. Jimmy Murray was the club's leading scorer with 21 goals in 28 games. He was followed by Peter Broadbent (20), Norman Deeley (17) and Bobby Mason (13).

In the 1959-60 season the club was beaten into second placed by Burnley. Once again Wolves were the top scorers in the league with 106 goals. This was 21 more than the champions who won the title by only one point. Top scorers were Jimmy Murray (29), Peter Broadbent (14), Norman Deeley (14), Bobby Mason (13), Des Horne (9), Eddie Clamp (8) and Ron Flowers (4).

Wolves also won the FA Cup in 1960 with Norman Deeley scoring two of the goals in the 3-0 victory over Blackburn Rovers. Deeley later recalled he could have had a hat-trick: "Barry Stobart made a good run down the left and got to the byline and whipped a cross in. I'd charged down the middle and Mick McGrath, the Rovers left-half, went with me. He actually reached the ball just before I did by stretching and sliding. With their keeper coming out to collect the cross I watched as the ball beat the keeper and rebounded off McGrath and into the net. It didn't really matter as I would have scored anyway."

In the 1960-61 season Wolves finished in 3rd place behind Tottenham Hotspur. The following season they finished 5th. Stan Cullis was surprisingly sacked in September 1964 after Wolves finished in 16th place in the league.

Primary Sources

(1) William McGregor, letter (2nd March, 1888)

Every year it is becoming more and more difficult for football clubs of any standing to meet their friendly engagements and even arrange friendly matches. The consequence is that at the last moment, through cup-tie interference, clubs are compelled to take on teams who will not attract the public.

I beg to tender the following suggestion as a means of getting over the difficulty: that ten or twelve of the most prominent clubs in England combine to arrange home-and-away fixtures each season, the said fixtures to be arranged at a friendly conference about the same time as the International Conference.

This combination might be known as the Association Football Union, and could be managed by representative from each club. Of course, this is in no way to interfere with the National Association; even the suggested matches might be played under cup-tie rules. However, this is a detail.

My object in writing to you at present is merely to draw your attention to the subject, and to suggest a friendly conference to discuss the matter more fully. I would take it as a favour if you would kindly think the matter over, and make whatever suggestions you deem necessary.

I am only writing to the following - Blackburn Rovers, Bolton Wanderers, Preston North End, West Bromwich Albion, and Aston Villa, and would like to hear what other clubs you would suggest.

I am, yours very truly, William McGregor (Aston Villa F.C.)

(2) Wolverhampton Express and Star (10th April 1932)

By his splendid work with the Wolves he has built up a reputation as a football manager second to none in the country. The Major created a big impression as the manager of Blackpool when he came to the Wolves. At the Molineux Ground he has proved himself a splendid judge of a player. His ability to find a young talent is unequalled and despite the handicaps with which he is faced when joining the club he has discovered a whole team, which has taken Wolves into the highest flight.

(3) Stan Cullis, All For the Wolves (1960)

Buckley spent many hours drilling me in the precious art of captaincy, telling me in no ambiguous terms that I was to be the boss on the field. No youngster of eighteen could ask for a better instructor than the major, who laid the foundations of the modern Wolves during his sixteen years at Molineux...

Throughout the middle years of the 1930s, Major Buckley steadily built up the team he believed would capture most of the honours in England. From the large numbers of lads he brought to Molineux for trials, he signed enough professionals both to form his team and to bring in a fortune from the transfer market. At a time when a five-figure transfer fee still astounded the football public, Major Buckley earned £130,000 for Wolves in five years before the 1939-45 war. This spell established Wolves as one of the wealthiest football clubs in Britain.

(4) Ron Flowers, For Wolves and England (1962)

Mr. Cullis, as our chief, and the mainspring on the playing side, possesses a tenacity and drive few other men can equal. As I remarked earlier, I do not always agree with him, but there is no disputing he has in every way proved himself to be one of the most successful managers in modern football. The Stanley Cullis approach to the problems of modern football always makes interesting hearing, and reading, for he thinks most seriously about all aspects of the game and his reactions often intrigue me.

Many managers, when a team is passing through a lean spell, would prefer to sit down and talk over the current problems with his players. But not our chief. As a former player of distinction, he realizes that a player knows when he is playing badly and must be worried.

He never adds to our worries at such a time by large-scale inquests, and I for one deeply appreciate this

approach. Our manager, on the other hand, has very thorough and searching tactical talks when we're doing well, which over the past ten years means we've had plenty of discussions.

One of the great qualities of Stanley Cullis as a manager is that he knows what he wants. The "boss" likes to hear our ideas, and encourages us to air our views. But as our manager he'll tell us when he disagrees, and straight from the shoulder say what he requires from us all.

On a Saturday, if we have not had a team talk, he will always come to the dressing-room before the match to have a word with certain players to discuss the men opposing them. Mr. Cullis's advice is always on target.

During the course of a season our manager spends as much time as possible watching the teams we will oppose. He makes a mental note of the players we will be meeting and he has what I can only term a photographic mind. If Stanley Cullis tells you that your opponent has certain strong qualities, and weaknesses, you can be certain he is giving you the right advice.

In setting out to achieve success on the field for Wolverhampton Wanderers our manager never sets out to copy the tactics of any other club. He has his own individual approach to the game. It is an outlook that has brought with it success to his teams, and, briefly, I think his basic plan is to split the field into three parts. One third of the pitch contains our goalmouth; one third is mid-field; the final third is our opponents' section of the field.

The Wolves plan is a simple one to follow. The idea is to get the ball as often as possible into the third of the field defended by our opponents, for it is from this position the Wolves score their goals.

(5) Stan Cullis, All For the Wolves (1960)

Often Mullen and Hancocks would find one another with long passes which travelled from one touchline to the other twice during the course of an attack. When the ball came into the middle, the defence was often caught in a line straight across the field and Swinbourne, Wilshaw or one of the other forwards was presented with a reasonable chance to score.

At the end of the 1949-50 season, in which we concentrated hard on improving the efficiency of these two fine wingers, Wolves finished second in the Championship, losing first place to Portsmouth only on goal-average.

In later seasons, we were able to gain further advantages from Hancocks's ability to place his passes so accurately. The club paid a big fee to Brentford for the transfer of Peter Broadbent, a 17-year-old inside-forward from Dover, who, I thought, could well develop into one of the outstanding inside-forwards of his day. Broadbent, in addition to the normal qualities of an inside-forward, also had considerable pace, and a flair for going past a defender in the fashion of a winger.

Consequently, we often used him as an advanced winger lying on the touchline twenty yards or more ahead of Hancocks. When the ball came out of defence to Hancocks, he was able to chip it accurately to Broadbent who was frequently clear on his own. This stratagem, designed to make the fullest use of the best qualities of both players, was also extremely successful, for the full-back marking Hancocks was caught between two men and played out of the game.

As we were working largely to the law of averages, determined to ensure that the ball spent a far larger proportion of each match in front of the opposition goal than in front of ours, it is a logical sequel that, once we had put the ball into the other team's danger area, we could not afford to allow them to obtain possession of it without a fight. So I needed forwards who could challenge and tackle and struggle for every loose ball.

In 1950, I was fortunate in that I had an ideal player for this type of game in Roy Swinbourne, the young Yorkshireman who came to Molineux from Wath Wanderers, the nursery team of Wolves which is run by Mark Crook, one of our old players. Tall and strong, Swinbourne could gain possession of the ball on the ground and, in the air, he could beat most defenders. As he learned, and removed the rough edges from his game, he developed into a first-class centre-forward for Wolves and was just coming to the peak of his career when he injured a knee in the last minute of a game at Preston.

This unfortunate injury happened early in the 1955-6 season and, although he tried for nearly two years to find his old speed, Swinbourne never recovered from that accident and now he has to be content to referee local games in Wolverhampton. Although the game may have found a first-rate official, football lost a potentially great centre-forward.

At the time of Swinbourne's accident, I knew that Wolves would find it very difficult to replace a key man in the tactical plan. I did not realize that, three years later, as we played in the European Cup for the first time, I would still be without an adequate substitute.

For Swinbourne was one of the few powerful forwards in the modern game who could fight and tackle for every ball in the manner of Peter Doherty, Raich Carter or Jimmy Hagan.

(6) Norman Deeley, Match of My Life (22nd September 2007)

You don't tend to settle down in the first five minutes or so. My stomach butterflies stopped after that and I felt much more with it, settled and concentrated. Blackburn did create one decent early chance when Peter Dobing went through on Malcolm Finlayson, but Malcolm saved at his feet and that turned out to be their only real chance. We started to play a bit then too. My job was always to get into the box from the right-hand side when the ball was on the left wing. It had worked the opposite way round for my goal which won the semi-final. Anyway, Barry Stobart made a good run down the left and got to the byline and whipped a cross in. I'd charged into the middle and Mick McGrath, the Rovers left half, went with me. He actually reached the ball just before I did by stretching and sliding. With their keeper coming out to collect the cross I watched as the ball beat the keeper and rebounded off McGrath and into the net.

It didn't really matter as I would have scored anyway. Once the ball had beaten the goalkeeper, if Mick had missed it I was only a couple of yards behind him waiting to tap it in. But own goals are a nightmare to put behind you at the best of times and this one was in the biggest game of all. As it turned out that cost me a hat-trick in the FA Cup final. If only you'd missed it, Mick! I'm sure you wish you had too.

As I was racing in behind him ready to score I couldn't stop myself from following the ball into the net and clinging onto the rigging in celebration. I didn't normally celebrate too much, not like they do these days, but a goal at Wembley is special...

As we walked off the pitch after the half-time whistle, BBC TV asked me if it was actually my goal. Live on air, at half-time! I told the nation that Mick had scored it. I could have claimed the goal then and I would have had my hat-trick, but I knew Mick had got the touch not me and I thought it was obvious. I also didn't know what destiny had in store for me in the second half.

When we got into the dressing room all Stan said to us was "Keep going". I saw him change his shirt as the one he was wearing was wringing with sweat. It was a hot day, but I think he was so nervous, with us being favourites and then having the man advantage. He didn't want us to make any silly mistakes. We didn't have that luxury. I remember my shirt was wet through too, although at least I'd been running around! But we couldn't change. To be honest I had been hotter the previous summer when I'd played for England on tour in South America.

We played extremely competently in the second half. Blackburn didn't really threaten us. But we still needed another goal before we could say "That's it." And it came my way. Des Horne crossed from the left towards me. I was running into the area and hammered it first time. I knew it was in as soon as I stuck it and when it hit the back of the net it felt tremendous. There was even some controversy about this goal as Blackburn claimed Horne was offside. But what happened was that McGrath was standing on the goal-line playing him onside and he jumped off the pitch backwards leaving Des technically offside. But the referee allowed play to continue. Quite rightly in my opinion as I scored!

At least we'd scored a goal ourselves, rather than just win the Cup with an own goal. No-one got over-excited. I just got a pat on the back and a couple of handshakes. I think a bit of the shine had been taken off the whole thing for a lot of the lads by Blackburn going down to ten men. And anyway, we were always of the opinion that it was a team effort. In those days it really was. None of these individualist stars. In fact if anything the real stars were the players who made goals rather than those that finished them off that won the plaudits.

Then I scored again. Des Horne played a short corner routine and crossed it into the box. He mishit it a bit and the ball actually hit the post and came out in front of goal. Woods tried to clear it, but he mishit it too. It fell to me perfectly on the volley. I timed it well and hit it.

I had spent hours in the "Dungeon" beneath the stands at Molineux banging balls off the rugged walls and practicing shooting on the volley. That paid off then as I turned and hit it cleanly. There was just that small delay while I saw the ball fly into the net and then I knew it was all over. 3-0 versus ten men. We'd won.

(7) Ron Flowers, For Wolves and England (1962)

Let's run through a typical "Wolves Week".

Monday: If the team has played reasonably well on the preceding Saturday, and no inquest is necessary, most of us have a hot soda bath, which brings out all the bruises, aches, and pains. On the other hand, if we've had a poor match the outcome is usually travel by coach to our training ground at Castlecroft, and Bill Shorthouse, the club coach, examines our mistakes.

Our coach attends all the League team matches, and naturally studies, probably more closely than anyone else on the ground, the team and individual displays. Sometimes, when we go to Castlecroft, manager Stanley Cullis also attends. And after our inquest the exercise usually concludes with a practice match under the direction of Bill Shorthouse.

We then return to the ground, have a bath, and the rest of the day is free.

Tuesday : This is an athletics morning, and we train at the Aldersley Stadium under the direction of Frank Morris, a well-known international runner, a qualified coach, and, as it so happens, a very keen supporter of the Wolves. Mr. Morris, however, much as he may admire our club, still puts the emphasis upon hard work once we arrive at Aldersley Stadium.

The morning starts with lapping in our gym shoes, and we usually cover around three miles. This is followed by body exercises, and then we put on our spikes and really enjoy ourselves. Frank Morris, quite rightly, understands the importance of competition to keep everyone interested, and our sprinting, hurdling, and running in general is based upon team competition.

Sometimes we have 440-yard races and relay races, and, let me repeat, the emphasis all the time is on getting superbly fit, but at the same time maintaining interest in our training.

When our morning has been completed at Aldersley Stadium we return to Molineux. In many instances we get into our cars, drive home for lunch, and report back to the club at two o'clock for another training session, this time under Joe Gardiner, the club trainer.

Tuesday-afternoon training consists of circuit training, with our trainer, a former Army P.T.I., really putting everyone on their toes. We include weight-lifting, squats, press-ups, and dumb-bells in our circuit.

Altogether we go round the circuit three times. Afterwards we have stomach exercises, and finish the afternoon with a six-a-side on the car park. We have completed our training by about four o'clock in the afternoon, and, as you may have gathered, following these exertions we are all ready for tea and maybe a rest in front of the fire.

Wednesday: After reporting at Molineux - every player has to sign a book so that the manager is aware if there are late arrivals-we travel by coach to the training ground at Castlecroft. Our first assignment is to loosen up by lapping the ground about a dozen times. Then, with coach Shorthouse, and often manager Cullis, we get down to the very serious business of work with the ball. Coaches such as Bill Shorthouse and his Wolves predecessors, George Poyser and Harry Potts, now Burnley's manager - are men brimful of ideas. They get players talking seriously about the game, and at Castlecroft we often find Bill putting into practice the ideas we may have put forward, which, in all walks of life, makes a fellow feel a little pleased with himself. On Wednesday morning we practise moves; maybe I spend some time working out throws-in with Peter Broadbent or other forwards.

The value of having a former Wolves player such as Bill Shorthouse in the role of coach can be appreciated by a player like me who has been some time with the club. Bill knows just what manager Cullis wants from us. He can guide us into playing the type of game our boss demands. And to a player assisting a club with a set style of play this guidance is of the utmost value.

Although our manager is a straight-speaking character who never hesitates to tell a player when and where he has gone wrong, I always enjoy his presence at a practice match. The former England centre-half has a wonderful eye for detecting what is wrong, and knows how to rectify the problem. When once he starts talking over such problems I always find myself absorbed by his intelligent and constructive approach to football as a whole.

After our work at Castlecroft we have the rest of the day to ourselves.

Thursday: Another athletics morning at Aldersley under Frank Morris's direction. In view of the Saturday match in two days' time the importance of conserving energy is appreciated, so after six laps of the track Morris concentrates upon body and breathing exercises. Once again I should like to stress how I understand why Mr. Morris takes this angle, for there have been occasions in the past when I have felt on a Thursday that we have tried far too hard, and the outcome has been-speaking purely for myself - a footballer who has felt rather tired when match day arrived.

There are Thursdays, I might add, when Mr. Morris takes us over to Cannock Chase for a jog, long walk, and deep-breathing exercises.

From a fitness point of view Frank Morris's athletics training has helped a large number of the players on the staff at Molineux. In my own case Mr. Morris taught me how to use my arms correctly to get "push", and there is little doubt this has added to my speed. Jimmy Murray, the Wolverhampton Wanderers and England Under-23 centre-forward, is one more player who has improved his play because of Mr. Morris's influence and knowledge. At one time Jimmy, whenever he went up to head a ball, landed on one foot. Naturally he was off balance and could not move quickly to join an attack. Once more Mr. Morris stepped in. He put Jimmy through a course of high-jumping, and Murray soon began to land on two feet. This also applied when he went up to head a ball on the football field. To many, following this coaching course, he may have appeared to be a much speedier player, but actually the small but vital point of landing on both feet was the real basis for his all-round improvement.

Friday: This is pay-day, and before reporting for training most of us receive our cheque. At Molineux this practice, which has been adopted recently by many other clubs, has been an accepted rule ever since I joined the Wolves. On Friday, too, this is the only day we stay at Molineux. Usually we loosen up in our spikes on the cinder track surrounding the pitch, perhaps have a kick-about on the car park, or a spell in the shooting-pen, and complete the morning of light work by having a massage. The afternoon is free.

Saturday : The day for which we have been preparing all week. I usually lie in bed until nine o'clock, read the papers, take my son Glen for a walk, and then, after a light lunch, report at the ground about an hour and a half before the start of the game. I'm one of those fellows who prefer to take things easily, and would far rather have plenty of time to spare, so that I can prepare carefully for a game, instead of rushing along at the last moment. After all, as it says on the wall of the Wolves dressing-room: "There's no substitute for hard work." Neither, come to that, does the good footballer go on to the field until he has thoroughly checked over his boots and other gear, and, at the same time, acquired the poise so essential if any sportsman is to produce the best performance of which he is capable.