Alex James

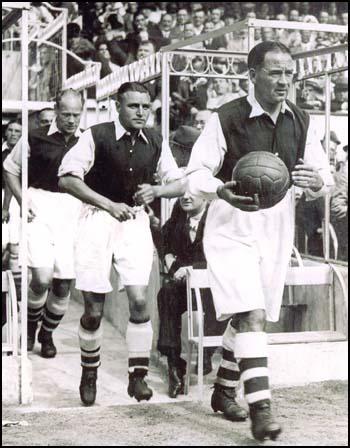

Alexander (Alex) James was born in Mossend, Scotland, on 14th September, 1901. He played local football for Brandon Amateurs, Orbiston Celtic and Glasgow Ashfield before joining Raith Rovers in the Scottish League. James made his league debut in September 1922 against Celtic.

Alex James scored 28 goals in 98 games in the three years he was at Raith Rovers. In 1925 Frank Richards, the manager of Preston North End, paid £3,000 for James. He also purchased his teammate, David Morris, and the captain of the Scottish national team, at the same time.

James did well in his first season ending up as the club's top scorer with 14 league goals. He also won his first international cap when he played in Scotland's 3-0 victory over Wales in October, 1925.

In the 1926-27 season Alex James developed a good partnership with centre-forward, Tommy Roberts, who had returned to the club after spending a couple of seasons at Burnley. Preston finished in 6th position in the 1926-27 season, with Roberts scoring 30 goals.

Tommy Roberts was involved in a serious car accident and was forced into retirement. He was replaced by Norman Robson who managed 19 goals in 22 appearances. That year Preston finished in 4th position. The following year he was paired up with fellow Scotsman, Alex Hair, who ended up as top scorer with 19 goals.

Alex James attracted the notice of all the top clubs when he scored two spectacular goals in Scotland's 5-1 victory over England at Wembley on 31st March, 1928.

In four years at Preston North End Alex James had scored 55 goals in 157 appearance. He also supplied the passes that resulted in plenty of goals for his strike partners, Tommy Roberts, Norman Robson and Alex Hair.

As a schoolboy, Tom Finney, used to watch James play at Deepdale. "James was the top star of the day, a genius. There wasn't much about him physically, but he had sublime skills and the knack of letting the ball do the work. He wore the baggiest of baggy shorts and his heavily gelled hair was parted down the centre. On the odd occasion when I was able to watch a game at Deepdale, sometimes sneaking under the turnstiles when the chap on duty was distracted, I was in awe of James. Preston were in the Second Division and the general standard of football was not the best, but here was a magic and a mystery about James that mesmerised me."

James had become frustrated with playing Second Division football. He was also upset with Preston North End for not always releasing him to play international games for Scotland. Most of all, he was dissatisfied with his wages. At the time, the Football League operated a maximum wage of £8 a week. However, other clubs had found ways around this problem. This included Arsenal who signed James for £8,750 in 1929. Herbert Chapman, the manager of Arsenal, arranged for James to obtain a £250-a-year "sports demonstrator" job at Selfridges. It was also agreed that James would be paid for a weekly "ghosted" article for a London evening newspaper.

Alex James had been a goalscoring inside-forward at Preston North End. However, Herbert Chapman wanted him to plat the role of link man in his system. As Chapman later pointed out: "He had his ideas as to how he should play, but they did not quite fit in with those we favoured, and it was necessary that he should make some change." James found it difficult to adapt to this role and Arsenal started the 1929-30 season badly. In a cup-tie against Chelsea Chapman dropped James from the team. Arsenal won the game and James was not recalled until he had convinced Chapman that he was willing to play the link man role.

Herbert Chapman gradually adapted the "WM" formation that had originally been suggested by Charlie Buchan. Chapman used his full-backs to mark the wingers (that job had previously been done by the wing-halves). He also developed what became known as the counter-attacking game. This relied on the passing ability of Alex James and goalscoring forwards like David Jack, Jimmy Brain, Joe Hulme, Cliff Bastin, and Jack Lambert. Chapman also built up a good defence that included players such as Bob John, Eddie Hapgood, Herbert Roberts, Alf Baker, Tom Parker and George Male.

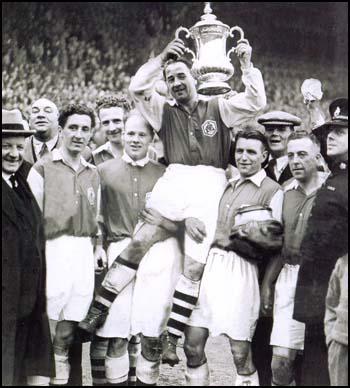

Success was not immediate and Arsenal finished in 14th place in the 1929-30 season. They did much better in the FA Cup. Arsenal beat Birmingham City (1-0), Middlesbrough (2-0), West Ham United (3-0) and Hull City (1-0) to reach the final against Chapman's old club, Huddersfield Town. At the age of 18 years and 43 days, Cliff Bastin was the youngest player to appear in a FA Cup Final.

Eddie Hapgood later described the role that Alex James played in the 2-0 victory. "Alex was fouled somewhere near the penalty area, and, almost before the ball had stopped rolling, had taken the free-kick. He sent a short pass to Cliff Bastin, moved into position to take a perfect return, and banged the ball into the Huddersfield net for the all-important first goal. Tom Crew told me that James made a silent appeal for permission to take the kick, and he waved him on. It was one of the smartest moves ever made in a big match and it gave us the Cup. I contend that it was fair tactics; for if Alex had waited a few seconds for the whistle, the Huddersfield defence would have been in position, and the advantage of the free-kick would have been lost." Jack Lambert got the second goal late in the second half, also from a move started by Alex James.

The following season Arsenal won their first ever First Division Championship with a record 66 points. The Gunners only lost four games that season. Jack Lambert was top-scorer with 38 goals. Other important players in the team included Alex James, Frank Moss, Alex James, David Jack, Cliff Bastin, Joe Hulme, Eddie Hapgood, Bob John, Jimmy Brain, Tom Parker, Herbert Roberts, Alf Baker and George Male.

Arsenal began the season badly. West Bromwich Albion won at Highbury in the opening game and victory did not come until the fifth match, at home to Sunderland. Arsenal's main problem was a lack of goals from Jack Lambert who was suffering from an ankle injury. However, Lambert recovered his goalscoring touch and Arsenal went on a good run and gradually began to catch the leaders, Everton.

Arsenal also did well in the FA Cup. They beat Plymouth Argyle (4-2), Portsmouth (2-0), Huddersfield Town (1-0), and Manchester City (1-0) to reach the final. Arsenal's league form was also good and after the FA semi-final they were only three points behind Everton, with a game in hand. This was followed by victories over Newcastle United and Derby County and it seemed that Arsenal might win the cup and league double.

The next game was against West Ham United at Upton Park. After two minutes Jim Barrett went for a loose ball with Alex James. According to Bernard Joy: "James chased after it, both went awkwardly into the tackle and as James slipped, down came the full weight of Barrett's fifteen stone on to his outstretched leg." James had suffered serious ligament damage and was unable to play for the rest of the season. Arsenal missed their playmaker and won only one more league game and Everton won the title by two points.

The Arsenal managing director at the time, George Allison said of Alex James: "No one like him ever kicked a ball. He had a most uncanny and wonderful control, but because this was allied to a split-second thinking apparatus, he simply left the opposition looking on his departing figure with amazement."

Arsenal won the First Division by four points in the 1932-33 season. Alex James was in fine form. So also was Cliff Bastin, the team's left-winger, was top scorer with 33 goals. This was the highest total ever scored by a winger in a league season. Joe Hulme, the outside right, contributed 20 goals.

This illustrates the effectiveness of Chapman's counter-attacking strategy. As the authors of The Official Illustrated History of Arsenal have pointed out: "In 1932-33 Bastin and Hulme scored 53 goals between them, perfect evidence that Arsenal did play the game very differently from their contemporaries, who tended to continue to rely on the wingers making goals for the centre-forward, rather than scoring themselves. By playing the wingers this way, Chapman was able to have one more man in midfield, and thus control the supply of the ball, primarily through Alex James."

Jeff Harris argues in his book, Arsenal Who's Who: "The reason that Bastin was so deadly was that unlike any other winger, he stood at least ten yards in from the touch line so that his alert football brain could thrive on the brilliance of James threading through defence splitting passes with his lethal finishing completing the job."

Matt Busby was playing for Manchester City at the time. He later recalled: "Alex James was the great creator from the middle. From an Arsenal rearguard action the ball would, seemingly inevitably, reach Alex. He would feint and leave two or three opponents sprawling or plodding in his wake before he released the ball, unerringly, to either the flying Joe Hulme, who would not even have to pause in his flight, or the absolutely devastating Cliff Bastin, who would take a couple of strides and whip the ball into the net. The number of goals created from rearguard beginnings by Alex James were the most significant factor in Arsenal's greatness."

Tommy Lawton argued that James " was often described as being slow, but I have seen the little Scot move at breakneck speed. His greatest weapon was his ability to feint, either with his foot or with his head. I have seen him stand still, swaying like a snake under the influence of the charmer, and scatter experienced defenders this way and that."

Stanley Matthews was another player who appreciated James' talents: "Alex supplied the ammunition for his fellow Gunners and was widely regarded as the most astute football tactician of his time. It is no exaggeration to say that Arsenal manager Herbert Chapman built his team around him. The Arsenal of the day were a team of rare talent and Alex James was its mastermind, though you would never suspect it on seeing him.... There were many who believed his carefree appearance was natural, others thought it all part of a pose, but it was in sharp contrast to one of the tidiest and sharpest football brains there has ever been. He hated wasted effort. To him it was a mark of poor technique and indicative of a poor footballing brain. For all he could be intolerant of those who did not match up to his classical artistry, he was the arch entertainer - a diminutive Scottish comic who held his audience and opponents spellbound until he delivered his killer punchline.

Sunderland were Arsenal's main challengers in the 1933-34 season thanks to a forward line that included Raich Carter, Patsy Gallacher, Bob Gurney and Jimmy Connor. In March 1934 Sunderland went a point ahead. However, the Gunners had games in hand and they clinched the league title with a 2-0 victory over Everton. One of the goals was scored by goalkeeper Frank Moss who suffered a dislocated shoulder and was forced to play on the left-wing for the remainder of the game.

According to Frederick Wall, the president of the Football Association, Alex James was the best player he saw in 50 years of watching football: "Alex James never suppresses himself. He may conceal his intention, he may lead a man away on the wrong trail, he may hold the ball and invite a tackle, he may fool an opponent who becomes ruffled, and he may do the most unexpected thing in a flash, but he does not seem to care what may happen to himself... Alex James is the greatest of all the outstanding players of his period, and, in my judgment, he would have been just as masterful, whimsical, and self-possessed in any period when football has been an organized, collective and disciplined game."

The 1935-36 season was not so good for Arsenal, finishing in 6th place behind Sunderland. However, James did captain Arsenal to a FA Cup Final win against Sheffield United. James was now 35 years old and could no longer recapture his best form.

James retired from football in 1937. During the Second World War he served in the Royal Artillery. After the war he worked as a journalist until taking up a coaching role with Arsenal in 1949.

Alex James died of cancer at the age of 51 on 1st June, 1953.

Primary Sources

(1) Tom Finney, My Autobiography (2003)

Although football dominated my early life - that should probably read my entire life come to think of it - opportunities for watching the game were restricted. Apart from anything else, I was always too busy playing. But as a proud Prestonian, I was acutely aware of Preston North End Football Club and, in common with the other lads who kicked a rubber ball around the back fields of Holme Slack, my dream was to be the next Alex James.

James was the top star of the day, a genius. There wasn't much about him physically, but he had sublime skills and the knack of letting the ball do the work. He wore the baggiest of baggy shorts and his heavily gelled hair was parted down the centre. On the odd occasion when I was able to watch a game at Deepdale, sometimes sneaking under the turnstiles when the chap on duty was distracted, I was in awe of James. Preston were in the Second Division and the general standard of football was not the best, but here was a magic and a mystery about James that mesmerised me.

The man behind Preston's capture of James was chairman Jim Taylor, who later signed me and went on to play a major part in my early career.

The son of a railwayman and a native of North Lanarkshire, Alex James was a steelworker when his football talents were first spotted by Raith Rovers in the year of my birth. He earned good money north of the border - £6 in the winter and £4 in the summer - and his form brought the scouts flocking in. Preston were always well served with 'spies' in Scotland and while his short stature and dubious temperament caused a few potential buyers to dither, Jim Taylor was more bullish. In the June of 1925, the chairman went in with a £2,500 bid - an offer later raised to £3,500 to ward off a late inquiry from Leicester City. Taylor had his man and the signing of James proved a masterstroke. The supporters loved him, a fact reflected in the attendances, which rose by around £300 per game. He was box office, the draw card, a player who grabbed your attention and refused to let go.

James was a character off the field, too. He liked clubs - of the night-time variety - owned a car and, by all accounts, enjoyed playing practical jokes on his colleagues. But he was also a perfectionist, a footballer acutely aware of both his ability and his responsibility. The experts scratched their heads about why his talent was being allowed to languish outside the top flight and it wasn't long before Arsenal came in to present him with a bigger stage. He was my first football hero and my role model and when he was transferred to the Gunners I thought I would never get over it.

The kickabouts we had in the fields and on the streets were daily events, sometimes involving dozens and dozens of kids. There were so many bodies around you had to be flippin' good to get a kick. Once you got hold of the ball, you didn't let it go too easily. That's where I first learned about close control and dribbling.

It was a world of make-believe - were children more imaginative in those days? - and although we only had tin cans and school caps for goalposts, it mattered not a jot. In my mind, this basic field was Deepdale and I was the inside-left, Alex James. I tried to look like him, run like him, juggle the ball and body swerve like him. By being James, I became more confident in my own game. He never knew it, but Alex James played a major part in my development.

(2) Eddie Hapgood, Football Ambassador (1945)

During the season which ended in April 1929, I had finally clinched my place in the Arsenal first team, while Herbert Roberts, Charlie Jones and Jack' Lambert had also made their appearance. During the following summer, Herbert Chapman made two of his greatest "buys," to change, materially, the fortunes of our club.

He signed Alexander James and Clifford Sydney Bastin.

James was 28 and brought, from Preston, a reputation which cost Arsenal £9,000; Bastin was barely seventeen and had been a professional footballer a matter of weeks. What a contrast - and what a wing.

Brought together from clubs as far apart as Preston and Exeter; one a tough little Scot from Bellshill, hard as a nut, commercially-minded, determined to get much out of football, who had joined Arsenal because it offered the best possibilities of improving his position ; the other, the son of sturdy West Country folk, who was born to be great, quiet, reserved, but, even then, with the infinite ability of being able to play football with the touch of the master... their destinies were irretrievably interwoven. The James-Bastin wing was a natural.

It was with more than ordinary interest that I met Alex when we reported from training that August. I had met one with an accent like Alex's. But when I got to understand his dialect, we had much to do with each other. Alex believes in speaking his mind, a failing, or virtue, of mine, so we had that in common.

Apart from his accent, Alex also had an amazing pair of legs " the most kicked legs in soccer," they were once called. However many times he was kicked during a match, and it was usually pretty often, the bruises never showed. And, frequently, until he got used to it, Tom would say Alex was swinging the lead, when he went to the Whittaker "surgery" for treatment.

(3) Tommy Lawton, My Twenty Years of Soccer (1955)

Alex James, with those incredibly long pants, was often described as being slow, but I have seen the little Scot move at breakneck speed. His greatest weapon was his ability to feint, either with his foot or with his head. I have seen him stand still, swaying like a snake under the influence of the charmer, and scatter experienced defenders this way and that. Yes, Alex was an incredible player, like Matthews, one who defies description.

(4) Frederick Wall, 50 Years of Football (1935)

When I look back over my football life and try to recall the players who have left abiding impressions upon me I feel compelled to ask myself one question: "Has the game ever had another Alex James?" Frankly, I have never seen another.

Commenting upon the players of my time, that is over a period of more than 60 years, as an amateur, as a referee, and as an administrative official, I have either watched or been in touch with many of the most renowned footballers.

There are men still alive and still interested in the sport whose names are more or less familiar to this generation because of their footwork, their quick wits on the field, and their physical courage.

It is possible to choose from them an ideal England eleven, each man a master and the whole likely to blend.

This would, of course, be a purely imaginative combination based on the assumption that every one of these eleven was now at his physical best and playing at the height of his power as a footballer.

And yet, when I look at the names, the question arises: Is there an Alex James among them all? Not to my mind.

I am much concerned about the few really great footballers there are in these days. They are so battered about and played on that sympathy is aroused for them.

This is not a covert suggestion that football is played in a foul manner. Considering how valuable League points are to the club, and remembering the almost overpowering desire to win ties in the Association Cup tournament, the games are cleanly and fairly contested. There is plenty of vigour and robustness, but these are everyday experiences. There are few games in which force supersedes skill.

Nevertheless, an effective player, whose anticipation, ready power of observation and quick, decisive action, make him the driving wheel of the machine, becomes a marked man. How often has it been said that "we must stop" James, or David Jack, Buchan, "Billy" Walker, Clem Stephenson, Billy Gillespie?

In every good team there is a commanding personality, an extra good player, who is a leader. To the ordinary spectator the team may seem to excel because of its collective strength-but the players know the man whose influence is felt, whose tactics and shrewd touches mean so much to the eleven. He is always a marked man.

But Alex James never suppresses himself. He may conceal his intention, he may lead a man away on the wrong trail, he may hold the ball and invite a tackle, he may fool an opponent who becomes ruffled, and he may do the most unexpected thing in a flash, but he does not seem to care what may happen to himself.

Do not be deluded by any praise bestowed upon the most celebrated men of former days, or by the prejudiced criticism of this day.

Alex James is the greatest of all the outstanding players of his period, and, in my judgment, he would have been just as masterful, whimsical, and self-possessed in any period when football has been an organized, collective and disciplined game.

I live more in the present than in the past. I am confident I have never seen another James, and it would be almost foolish to be sanguine of any club ever discovering his like.

It is customary for club managers and writers for newspapers to speak of A, B, or C as "another James"; as the material likely to develop into "another James."

Without being either cynical or sceptical, I shall only believe there is "another James" when he presents himself in action.

Apart from his trickery, juggling and ball control in little space, his ability to scheme, open up the game and set the forwards galloping, there is the mental equipment of the man. He is a Scotsman.

James is a man of extraordinary self-possession. He never loses himself-and rarely the ball. You may take the ball from him-if you can-but he never gives it.

This equanimity of mind is a tremendous asset. Excitement does not appear to be part of his make-up. However he may be played on, rolled on the ground, battered and bruised, hampered and hustled, he never betrays the least trace of resentment. If he has such a feeling it never can be inferred from his actions. However he may be nudged or buffeted, he picks himself up and goes on with the business he has to do.

The reader may say that a little fellow of 5 ft. 6 in., and under 11 stone, could not afford to be hasty in temper and resentful. That may be or may not be, but he is keen on what he believes to be his rights, and he can be stubborn. Yet on the field he is a model, and if there were 22 like him in a match the referee could be dispensed with.

His control of himself is as great a gift to him as his control of the ball. Nature's bounty and his own industry have made him the footballer he is. Such a combination is rare, and that is why I despair of ever again looking upon his like.

(5) Matt Busby, Soccer at the Top - My Life in Football (1973)

Alex James was the great creator from the middle. From an Arsenal rearguard action the ball would, seemingly inevitably, reach Alex. He would feint and leave two or three opponents sprawling or plodding in his wake before he released the ball, unerringly, to either the flying Joe Hulme, who would not even have to pause in his flight, or the absolutely devastating Cliff Bastin, who would take a couple of strides and whip the ball into the net. The number of goals created from rearguard beginnings by Alex James were the most significant factor in Arsenal's greatness.

(6) Stanley Matthews, The Way It Was (2000)

Arsenal were without doubt the top side in England during the thirties, winning the League Championship four times (1931, 1933-35) and the FA Cup twice (1930 and 1936). Alex supplied the ammunition for his fellow Gunners and was widely regarded as the most astute football tactician of his time. It is no exaggeration to say that Arsenal manager Herbert Chapman built his team around him. The Arsenal of the day were a team of rare talent and Alex James was its mastermind, though you would never suspect it on seeing him. While his team-mates would run on to the pitch for a game, James would shuffle on. He was a short, squat figure with bandy legs protruding from shorts so baggy it looked as if he was wearing a large white pillow case about his midriff. Toes turned in, sleeves down but always unbuttoned at the cuff, more often than not socks about his ankles, you would never think that this was a man who laid claim to genius.

His baggy shorts which hung well below his knees became his trademark and were as popular with cartoonists as Stanley Baldwin's pipe, Neville Chamberlain's umbrella or Winston Churchill's cigar. If you really want to know what society was like in years gone by, rather than read history books, look at the cartoons of the day. In retrospect, they capture a time perfectly. No footballer was portrayed more accurately or succinctly than Alex James.

There were many who believed his carefree appearance was natural, others thought it all part of a pose, but it was in sharp contrast to one of the tidiest and sharpest football brains there has ever been. He hated wasted effort. To him it was a mark of poor technique and indicative of a poor footballing brain. For all he could be intolerant of those who did not match up to his classical artistry, he was the arch entertainer - a diminutive Scottish comic who held his audience and opponents spellbound until he delivered his killer punchline.

Under Herbert Chapman he cut out the comedy some what and developed a taste for strategy, dominating the area of field between a resolute Arsenal defence as reluctant to push on as more contemporary Gunners defences have been, and a quicksilver forward line. Herbert Chapman's pre-match instructions to his team were as short as they were monotonous. "Give the ball to Alex," he would say and when they did, this unlikely looking hero single-handedly directed the Gunners offensive with seemingly consummate ease.

(7) Eddie Hapgood, Football Ambassador (1945)

My greatest Cup Final thrill was my first in 1930, I had only been in the Arsenal first team little over a year. We beat mighty Huddersfield that day, a great win, and a great moment for the Old Boss, who had made Huddersfield into a wonderful side, and who had then come on to make us an even greater team. That was the start of our great run. In the next eight years we won the League five times, were runners-up once and finished third on another occasion. We also won the Cup and were beaten in the Final.

There was a lot of newspaper criticism about our first goal. One school of thought had it that Alex James committed an infringement when scoring. Others argued that it was quite legal. We of the Arsenal contended then, and I do so now, that it was fair. And a conversation I had with Tom Crew, who refereed the game, some time later, bears out that contention.

Alex was fouled somewhere near the penalty area, and, almost before the ball had stopped rolling, had taken the free-kick. He sent a short pass to Cliff Bastin, moved into position to take a perfect return, and banged the ball into the Huddersfield net for the all-important first goal. Tom Crew told me that James made a silent appeal for permission to take the kick, and he waved him on. It was one of the smartest moves ever made in a big match and it gave us the Cup. I contend that it was fair tactics; for if Alex had waited a few seconds for the whistle, the Huddersfield defence would have been in position, and the advantage of the free-kick would have been lost. Jack Lambert got the second goal late in the second half, also from a move by Alex.

(8) Herbert Chapman, Herbert Chapman on Football (1935)

It will he recalled, too, that Alex James had an unhappy experience in the early part of the same season, and I shall always think that the dead set which was made against him was deliberately manufactured to hurt the club as well as the player. It was one of the meanest things I have ever known, and one of the finest players it has been my pleasure to see almost had his heart broken. That is not an exaggeration.

Like Jack, James was a much-boomed player when he joined us. In Scotland, where he was perhaps better known and appreciated than in England, though he had been nearly five years at Preston, he was known as "King James." He had his ideas as to how he should play, but they did not quite fit in with those we favoured, and it was necessary that he should make some change. He was always willing to do this, in fact, you could not wish for a better club man. However, before he had time to settle down to the Arsenal style, he was seriously upset by the bitter criticism to which he was subjected, and it was decided that the only thing to do was to allow him a rest.

I frankly admit, however, that I did not know how we were going to get him back into the side. It may be remembered how it was done, how he was taken to Birmingham, and brought out again in the replayed Cup tie with Birmingham. I am happy to say he has never looked back since, and that he has justified every hope and expectation. But the Arsenal nearly lost him, and if the worst had happened, those who had made the game a misery to him would have had to bear the blame.

(9) Richard Whitehead, The Times (23rd October, 2004)

James also arrived in North London in headline-making circumstances, but only after a prolonged Nicolas Anelka-like sulk had ensured his departure from Preston North End. James was keen to earn more than the £8-a-week maximum wage, but the only way for Arsenal to circumvent the Football League’s strict regulations was for their signing to take up additional employment as a “sports demonstrator” at Selfridge’s on the impressive salary of £250.

He was not an instant success — one sarcastic fan sent him a pair of battered child’s football boots with an accompanying note suggesting “it doesn’t matter much what you wear anyhow” — but James quickly became the brains behind a team that dominated domestic football in a fashion that had not previously been seen.

Lying deeper than conventional inside forwards, he would spring Arsenal’s rapid breakaways from defence — a tactic that earned them the tag “lucky Arsenal” from disgruntled opposing fans who had frequently seen their team dominate territorially for no tangible reward.

That tactic demonstrated the quality the little man with the commodious shorts shared most with his modern-day counterpart — the ability to hit passes so stunningly beautiful that they could adorn the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.