Stanley Matthews

Stanley Matthews, the son of a barber and professional boxer, Jack Matthews, was born in Hanley on 1st February, 1915. Jack Matthews took out his son training from an early age. His initial intention was for Stanley to become a boxer. However, Stanley had no interest in this sport. As he pointed out in his autobiography: "I had only one thing on my mind - to be a footballer."

Jack Matthews told his son that he could become a professional footballer "If you can make yourself good enough to be a schoolboy international before you leave school". Matthews achieved this when he played for England schoolboys against Wales when he was only 13 years old. England won the game 4-1.

In 1932 he signed for local club, Stoke City in the Second Division. The club got promoted to the First Division in the 1932-33 season. Matthews, who was only 18 years old at the time, won his first international cap for England against Wales on 29th September, 1934. The England team that day also included Eddie Hapgood, Ray Westwood, Cliff Britton and Eric Brook. Matthews scored one of the goals in England's 4-0 victory. He retained his place in the game against Italy on 14th November, 1934. A game that England won 3-2.

Stoke City struggled in the First Division and for a time he lost his place in the England side. On 17th April, 1937, he won his fourth international cap against Scotland. His wing partner that day was Raich Carter. However, the two men did not play well together and as a result Carter was dropped from the side. Tommy Lawton found the dropping of Carter inexplicable. "Raich was the perfect team man. He would send through pinpoint passes or be there for the nod down."

Raich Carter later explained why he never played well with Matthews: "He was so much of the star individualist that, though he was one of the best players of all time, he was not really a good footballer. When Stan gets the ball on the wing you don't know when it's coming back. He's an extraordinary difficult winger to play alongside."

One national newspaper even claimed that the other players in the team were so upset with Matthews that they refused to pass to him. Tommy Lawton admitted that: "We all had moments when we've been exasperated with Stan because he'd taken the ball off down the wing as if he was playing on his own." However, he rejected the idea that the players starved him of the ball because eventually "he'd produce a moment of sheer genius that nobody else could hope to match."

On 1st December, 1937, Matthews scored a hat-trick in England's 5-4 victory over Czechoslovakia. The England team that day also included Vic Woodley, Wilf Copping, Stan Cullis, Len Goulden, Willie Hall, John Morton and Bert Sproston.

In the 1937-38 season Stoke City finished in 17th place in the First Division of the Football League. Matthews was desperate to win league or cup medals and asked for a transfer. More than 3,000 fans attended a protest meeting and a further 1,000 marched outside the ground with placards. Matthews eventually agreed to stay.

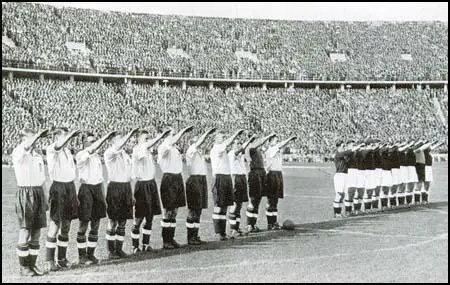

In May 1938 Matthews was selected for the England tour of Europe. The first match was against Germany in Berlin. Adolf Hitler wanted to make use of this game as propaganda for his Nazi government. While the England players were getting changed an Football Association official went into their dressing-room and told them that they had to give the raised arm Nazi salute during the playing of the German national anthem. As Matthews later recalled: "The dressing room erupted. There was bedlam. All the England players were livid and totally opposed to this, myself included. Everyone was shouting at once. Eddie Hapgood, normally a respectful and devoted captain, wagged his finger at the official and told him what he could do with the Nazi salute, which involved putting it where the sun doesn't shine."

The FA official left only to return some minutes later saying he had a direct order from Sir Neville Henderson the British Ambassador in Berlin. The players were told that the political situation between Britain and Germany was now so sensitive that it needed "only a spark to set Europe alight". As a result the England team reluctantly agreed to give the Nazi salute.

The game was watched by 110,000 people as well as senior government figures such as Herman Goering and Joseph Goebbels. England won the game 6-3. This included a goal scored by Len Goulden that Matthews described as "the greatest goal I ever saw in football". According to Matthews: "Len met the ball on the run; without surrendering any pace, his left leg cocked back like the trigger of a gun, snapped forward and he met the ball full face on the volley. To use modern parlance, his shot was like an Exocet missile. The German goalkeeper may well have seen it coming, but he could do absolutely nothing about it. From 25 yards the ball screamed into the roof of the net with such power that the netting was ripped from two of the pegs by which it was tied to the crossbar."

On Friday, 1st September, 1939, Adolf Hitler ordered the invasion of Poland. On Sunday 3rd September Neville Chamberlain declared war on Germany. The government immediately imposed a ban on the assembly of crowds and as a result the Football League competition was brought to an end.

the picture is Eddie Hapgood and Wilf Mannion.

On 14th September, the government gave permission for football clubs to play friendly matches. In the interests of public safety, the number of spectators allowed to see these games was limited to 8,000. These arrangements were later revised, and clubs were allowed gates of 15,000 from tickets purchased on the day of the game through the turnstiles. The government imposed a fifty mile travelling limit and the Football League divided all the clubs into seven regional areas where games could take place.

During the Second World War Matthews served in the Royal Air Force. Like most top footballers, Matthews was stationed in England and was allowed to play in friendly games. This included guesting for Blackpool, Manchester United and Arsenal.

Neil Franklin was made captain of Stoke City in the 1946-47 season. Stories circulated that Matthews was dropped from the team by Bob McGrory and replaced by George Mountford because he was "unpopular" in the dressing-room. As his friend, Tom Finney, later explained: "Neil called a meeting of the players, sought their collective view, informed Stanley by letter of his intentions and strode off to see the board to quash the rumours and pay handsome tribute to his illustrious team-mate." Matthews later wrote: "The problem was not resolved, but knowing that I had the support of my team-mates, including George Mountford who had replaced me, made me feel a whole lot better about the whole sorry affair."

Matthews now lost his place in the England team. He now decided he must play for a club that had the possibility of winning the FA Cup or the league championship. On 10th May, 1947, Matthews was transferred to Blackpool for £11,500. This was a large sum of money to pay for someone aged 32 and considered past his best. However, Blackpool manager, Joe Smith, was extremely pleased with his signing. He joined a team that included Hughie Kelly, Stan Mortensen, Harry Johnson and Bill Perry.

In the 1947-48 season Blackpool beat Chester (4-0), Colchester United (5-0), Fulham (2-0), Tottenham Hotspur (3-1) to reach the final of the FA Cup. However, Blackpool lost the game 4-2 to Manchester United. Matthews played well that season and the Football Writers' Association (FWA) awarded him the first Footballer of the Year Award.

Matthews also regained his place in the England team and was a member of the team that had victories against Scotland (2-0), Italy (4-0), Northern Ireland (6-2), Wales (1-0) and Switzerland (6-0).

In the 1950-51 season Blackpool finished in 3rd place in the First Division of the Football League. Blackpool beat Stockport County (2-1), Mansfield Town (2-0), Fulham (1-0) and Birmingham City (2-1) to reach the final of the FA Cup. Once again Matthews only received a losing medal as Newcastle United won the game 2-0.

Stanley Matthews described Ernie Taylor as the "architect of our cup final defeat" urged the club manager, Joe Smith, to buy the man who was nicknamed "Tom Thumb". Matthews later recalled: "Ernie was a cheeky, confident player who on his day verged on the brilliant. Despite his slight build, he could ride even the most brusque of tackles with aplomb and he could crack open even the most challenging and organised of defences." Smith took the advice and in October 1951, paid £25,000 for Taylor.

In the 1952-53 season beat Huddersfield Town (1-0), Southampton (2-1), Arsenal (2-1) and Tottenham Hotspur (2-1) to reach the FA Cup final for the third time in five years. Cyril Robinson claimed that Joe Smith, the Blackpool manager "was never very tactical, he was very blunt with his instructions". According to Stanley Matthews he said: "Go out and enjoy yourselves. Be the players I know you are and we'll be all right."

Cyril Robinson was later interviewed about the match: "We kicked off and within a couple of minutes we had a goal scored against us. That's about the worst thing that could happen. Gradually we got some passes together, got Stan Matthews on the ball and Mortensen got the equaliser, but they went back ahead straight away."

Stanley Matthews wrote in his autobiography that: "At half-time we sipped our tea and listened to Joe. He wasn't panicking. He didn't rant and rave and he didn't berate anyone. He simply told us to keep playing our normal game." Harry Johnson, the captain, told the defence to "be more compact and tighter as a unit." He also added: "Eddie (Shinwell), Tommy (Garrett), Cyril (Robinson) and me, we will deal with the rough and tumble and win the ball. You lot who can play, do your bit."

Despite the team-talk Bolton Wanderers took a 3-1 lead early in the second-half. Robinson commented: "It looked hopeless then, I was thinking to myself at least I've been to Wembley." Then Stan Mortensen scored from a Stanley Matthews cross. According to Matthews: "although under pressure from two Bolton defenders who contrived to whack him from either side as he slid in, his determination was total and he managed to toe poke the ball off the inside of the post and into the net."

In the 88th minute a Bolton defender conceded a free kick some 20 yards from goal. Stan Mortensen took the kick and according to Robinson: "I've never seen one taken as well. It flew, you couldn't see the ball on the way to the net." Matthews added that "such was the power and accuracy behind Morty's effort, Hanson in the Bolton goal hardly moved a muscle."

The score was now 3-3 and the game was expected to go into extra-time. In his autobiography, Stanley Matthews described what happened next: "A minute of injury time remained... Ernie Taylor, who had not stopped running throughout the match, picked up a long throw from George Farm, rounded Langton and, as he had done like clockwork through the second half, found me wide on the right. I took off for what I knew would be one final run to the byline. Three Bolton players closed in, I jinked past Ralph Banks and out of the corner of my eye noticed Barrass coming in quick for the kill. They had forced me to the line and it was pure instinct that I pulled the ball back to where experience told me Morty would be. In making the cross I slipped on the greasy turf and, as I fell, my heart and hopes fell also. I looked across and saw that Morty, far from being where I expected him to be, had peeled away to the far post. We could read each other like books. For five years we'd had this understanding. He knew exactly where I d put the ball. Now, in this game of all games, he wasn't there. This was our last chance, what on earth was he doing? Racing up from deep into the space was Bill Perry."

Stanley Matthews added that Perry "coolly and calmly stroked the ball wide of Hanson and Johnny Ball on the goalline and into the corner of the net." Bill Perry admitted: "I had to hook it a bit. Morty said he left it to me, but that's not true, it was out of his reach." Blackpool had beaten Bolton Wanderers 4-3. Matthews, now aged 38, had won his first cup-winners medal.

Jimmy Armfield later pointed out: "We were standing at the end where the Blackpool goals went in on the way to that 4-3 victory in what will always be remembered as the Matthews final. Amazing that, when you think that Stan Mortensen became the only player to score a hat-trick in a Wembley FA Cup final.Morty had been suffering from cartilage trouble and he had an operation a few weeks before the game. He had hardly trained, yet he came out and scored a hat-trick." Interestingly, Stanley Matthews always insisted that he was overpraised for his performance that day and in his autobiography, The Way It Was, he called it the "Mortensen Final".

In the 1955-56 season Blackpool finished 2nd in the First Division of the Football League. That year Matthews was the winner of the first European Footballer of the Year award.

Matthews won his last international cap against Denmark on 15th May 1957. He was 42 years old. England won the game 4-1. Matthews had scored 11 goals in 53 appearances for England. Later that year he was awarded the OBE.

Matthews continued to play for Blackpool in the First Division of the Football League. However, in 1961 he rejoined Stoke City. Although he was now 46 years old he hoped he could help the club win promotion . The following season, the club won the Second Division Championship. He was also voted Footballer of the Year for the second time in his career.

Stanley Matthews played his final game for Stoke City on 6th February, 1965. He was 50 years old. During his career he had scored 71 goals in 701 league and cup games.

In 1965, he became the first football player to be knighted for services to sport. After retiring he was appointed as manager of Port Vale. He resigned in 1968 after it was alleged that illegal payments had been made to players. Port Vale were expelled, but subsequently re-instated to the Football League.

Matthews, who claimed that he had retired "too early" now moved to Malta where he joined Hibernians. He played his last game for them aged 55. He also played local football in his sixties. Matthews also coached in South Africa and Canada.

Stanley Matthews died on 23rd February 2000.

Primary Sources

(1) Stanley Matthews, The Way It Was (2000)

At 13 I had only one thing on my mind - to be a footballer. I had one more year at school before I had to go out and make a living. My father wanted me to be a boxer. Every morning at the crack of dawn, he would get me up and supervise a rigorous workout. One morning after an hour of intensive physical training, I broke down. I ran into the kitchen and vomited. Great beads of sweat formed on my brow and eventually I collapsed on the kitchen floor. My mother put me to bed.

I could hear her downstairs in the kitchen as usual. With a husband and four hungry lads to feed, my mother seemed to spend most of her life in the kitchen; these were the days when the only thing that could stir, mix, blend and whisk was a spoon and the only things that came ready to serve were tennis balls. Eventually my father came in and asked where I was. In those days, women rarely took issue with their husbands and she had never said a word about the training. For the first time in my life, I heard my mother get on to my father.

"Ever since Stanley said he didn't want to be a boxer there has been trouble between you two," she said.

It shocked me. It was like hearing Mother Teresa fly off the handle.

"Now it's gone too far. It's got to stop and I'm going to stop it."

I didn't hear my father say anything. I guess like me he was shocked to hear mother being so assertive.

"Haven't you got the sense to see he wants to do one thing and you want him to do another? Stanley wants to be a footballer and you can take it from me that from now on he's getting my support and encouragement. If you have anything about you Jack Matthews, you'll get up those stairs and tell your son you love him. Tell him that you've changed your mind and you're going to do everything in your power as his father to help him realise his dream. Do that Jack Matthews and for all we have nowt, you'll make him the happiest lad in Hanley and proud to be your son." Again there was silence.

"What would have happened if your father had wanted you to be a footballer instead of a boxer?" I heard my mother ask.

I heard my father's voice say, "I wouldn't have let him, simple as that."

"I know you wouldn't," my mother said. "You've always had a mind of your own. You were always crazy about boxing, but with Stanley, it's football. Go see him."

The stairs creaked like the timbers on an old sailing ship as my father made his way slowly up to my bedroom. I was lying with my back to him as he entered the room but he reached out and I turned towards him.

"Listen, son," he said. "I've been giving this football idea of yours some thought. If you can make yourself good enough to be a schoolboy international before you leave school, go for it! Are you on?"

I immediately sat bolt upright.

"It's a bet," I said, partly because I knew he was a betting man and partly because I didn't know what else to say.

The next morning he came into my bedroom at the crack of dawn with a football in his hand. I was back in training.

(2) Stanley Matthews, The Way It Was (2000)

I attended Wellington Road School in Hanley. I never distinguished myself as a scholar but in many respects I suppose I was a model pupil. I listened in lessons, was fair to middling academically, enjoyed school life and was never the source of any trouble.

All the spare time I had was taken up with playing football. When the school bell rang, I'd make my way home with a stone or a ball of paper at my feet. Once home, I'd make for a piece of waste ground opposite our house where the boys from the neighbourhood gathered for a kickabout. Coats would be piled for posts and the game of football would get under way. In fine weather it would be as many as 20 a side, in bad weather a hardened dozen or so made six a side.

I firmly believe that in addition to helping my dribbling skills, these games helped all those lads to become better citizens later in life. All such kickabout football games do. My reasoning behind this is quite simple. We had no referee or linesman, yet sometimes up to 40 boys would play football for two hours adhering to the rules as we knew them. When there was a foul, there would be a free kick. When a goal was scored, the ball would be returned to the centre of the waste ground for the game to restart. We didn't need a referee; we accepted the rules of the game and stuck by them. For us not to have done so, would have spoilt the game for everyone. It taught us that you can't go about doing what you want because there are others to think of and if you don't stick to the rules, you spoil it for everyone else. Of course, that was not a conscious thought at the time, but looking back, those kickabout games on the waste ground did prepare us for life.

(3) Stanley Matthews, The Way It Was (2000)

I thought my father had also been understanding in saying I could carry on with football if I made the England schoolboy team, even though it was a pretty tall order. I was of the mind that to be picked for England Schoolboys was something that happened to other boys, not me.

I felt I was making good progress. I often played at centre-half for my school and in one game scored eight in a 13-2 victory. I realised what a feat this was when my headmaster, Mr Terry, said how pleased he was with the way I had played and gave me sixpence. The youngest ever professional player?

It was around this time that another teacher at the school, Mr Slack, picked me at outside-right for the school team. I felt comfortable in the position; it provided more scope for my dribbling skills but I still thought centre-half was my calling. I must have been doing something right on the wing for later that year, I was selected to play for the North against the South in an England Schoolboy trial.

Even to this day, the lads picked for England Schoolboys tend to be the ones who have physically matured quicker than others. I was only 13, so in the physical stakes I was quite some way behind lads of 14 and 15. I felt I did all right in the trial, nothing exceptional, but the selectors must have seen something because three weeks later, I played for England Boys against The Rest at Kettering Town's ground.

I never heard another thing for months and was beginning to come to terms with the fact that at 13 I was probably a bit too young to get into the England Schoolboys team. I consoled myself with the thought that there would always be next season. I never stopped hoping, though, and I never stopped practising. I was doing so in splendid isolation, never realising that not every boy was getting up at the crack of dawn like me, going through a rigorous physical workout of sprints and shuttles and honing ball skills at every given opportunity. Such was my determination to master the ball and make it do whatever I wanted it to do.

A few months after the trial at Kettering, I was told to report to the headmaster's office. Such a call was about as bad as it could be. To be asked to report to the headmaster was a sure-fire way to immediate anxiety and guilt - a bit like your own mother saying, "Guess what I found in your bedroom this morning."

As I made my way to Mr Terry's office, I ran through all my recent escapades but couldn't come up with anything I d done that merited seeing the headmaster. On entering the office my stomach was churning. He indicated I should stand before his desk and then said, "Well, Matthews, let me congratulate you. You have been picked to play for England Schoolboys against Wales at Bournemouth's ground in three weeks' time. What do you think about that?"

I felt like saying, "Sorry sir, could you repeat that. I didn't hear you because of the sound of angels singing." Of course, I didn't. I just stood there dumbfounded. I could feel my face twitching, my mouth went dry and the shock made me sense I was about to embarrass myself with a bodily function. I tried to speak but the words wouldn't come. Instead, out of my mouth came the sort of noise a small frog with adenoid trouble would make - if frogs had adenoids, that is.

"I'm sorry to have given you such a shock, lad," Mr Terry said. `I had no idea it would upset you like this."

(4) Stanley Matthews, The Way It Was (2000)

Meeting my fellow team-mates for the first time had the same effect. Some of the boys seemed to know one another. I thought at the time this was probably down to the fact that they had played in previous schoolboy internationals or area representative games together. I was the only lad from Stoke-on-Trent. I didn't know anybody, no one knew me. It was the first time I had ever been in a hotel. A number of the other players seemed to know how to go on, but I simply hadn't a clue and was full of anxiety in case I made a dreadful faux pas. I had never been waited on at a table before and this made me feel awkward. I over-emphasised my thanks to everyone who placed a plate before me or took a bowl away, such was my embarrassment at having adults seemingly at my beck and call, not that I ever dared beckon or call anyone.

All of my team-mates were older than me. Although this was only a matter of a year, they all appeared so much more mature and worldly wise than me, as if they had done it all before, which several of them had. I'd always had confidence in my own ability but as I sheepishly hung on the perimeter of the social life at the hotel, I did wonder if I was going to be up to the mark. Would I cover myself in glory, or, having teamed up with those who were considered the best school-boy footballers in England and been pitted against the best Wales had to offer, find to my horror I was totally lacking? Would it be a case of being a big fish in a small pond in Stoke, but a floundering minnow when set alongside the cream of my contemporaries? This and my natural shyness made for a very quiet, passive and unassuming schoolboy international debutant in the build-up to the game.

When I ran down the tunnel for the first time in an England shirt, I was bursting with pride. The first sensation as the team emerged into the light was the noise of the supporters who had packed into the Dean Court ground. There must have been nigh on 20,000 there, which was far and away the largest crowd I had ever played in front of. I took a look around and the sight of so many people made me catch my breath. My heart was doing a passable impression of a kettledrum being played at full tempo, and as I ran around the soft turf, it was as if my boots would sink into it and never come unstuck. It was a terrific feeling, though. There and then, I knew that there couldn't be anything but a football career for me. It was one hell of a buzz and I felt so elated it was all I could do to stop myself shouting and screaming to release the excitement and emotion as I ran about in the warm-up.

I got an early touch of the ball from the kick-off and that settled me down. I started to enjoy the game and must admit I felt totally at home at outside-right. It was as if I had been born to it. We won 4-1 and, although disappointed that I didn't get on the scoresheet, I was happy enough with my overall contribution, having been involved in the build-up to a couple of our goals.

I had made a point of saying to my parents that I didn't want them to watch the game, partly because I thought it would unnerve me and partly because, with four sons to bring up, I knew they were on a tight budget and a trip to Bournemouth would have made quite a hole in my dad's weekly wage at the barber's shop. However, as I came off the field I felt sorry they weren't there. After all, you only make your debut for your country once.

In the dressing-room after the game, I was in the process of putting my boots into my bag when one of the officials came up and said there was someone outside the ground who would like a word with me. I made my way to the players' entrance and there was my father in his belted overcoat, clutching a brown paper bag in which he had his sandwich tin.

"Not so bad. I've seen you play better and I've seen you play worse," he said. "I've got just enough left for a cup of tea for the both of us, son. So let's have some tea, then we'll go home."

We walked in near silence towards a nearby cafe and I fought to hold back my tears. He may well have had only the price of two cups of tea in his pocket, but he was walking proudly with his head held high.

(5) Stanley Matthews, The Way It Was (2000)

When I ran out on to Gigg Lane with the rest of the Stoke team, I was as excited as I had been on my schoolboy international debut, perhaps more so. I noticed there was a cemetery backing on to one end of the ground and just hoped it wasn't an omen - the football career of Stanley Matthews was born and died here!

Within minutes of the kick-off I realised that first-team football was, quite literally, a totally different ball game. Arms were flaying when players came into close contact. Shirts were held. When I tried to get near an opponent with the ball, his arm would shoot out to keep me at bay. When standing alongside my opposite number and the ball came our way, he'd whack an arm across my chest to push me back and to lever himself forward. Whenever I saw a Bury player making progress with the ball and cut across to challenge him, one of his team-mates would run and block my way to allow him to progress. When a high ball came my way, I found I couldn't get off the ground to head it because the player marking me stood on my foot as he jumped to meet the ball with his head. Not once did the referee blow up for any of this. It was my first lesson that in professional football, such things are all part and parcel of the game. You have to accept them otherwise you just wither away. I was soon to learn that the best way of combating all this was to improve my individual skills and technique, to make it harder for my opponent to get near me and the ball. I toiled away, learning from my mistakes.

(6) Stanley Matthews, The Way It Was (2000)

The game got under way and from the very first tackles, I was left in no doubt that this was going to be a rough house of a game. I wasn't wrong. After a challenge between Drake and Monti, the Italian had to leave the pitch with a broken foot after only two minutes. This only made matters worse. For the first quarter of an hour there might just as well have not been a ball on the pitch as far as the Italians were concerned. They were like men possessed, kicking anything and everything that moved bar the referee. The game degenerated into nothing short of a brawl and it disgusted me...

Ted Drake latched on to an ale-house long ball out of defence and broke away to score a wonderful individual goal on his international debut. He paid for it. Minutes after the game re-started I watched in sadness as Ted was carried from the field, tears in his eyes, his left sock torn apart to reveal a gushing wound.

I thought the three quick goals would calm the Italians down, showing them that rough-house play didn't pay dividends, but they got worse. I felt it was a great shame they had adopted such tactics because individually they were very talented players with terrific on-the-ball skills. They didn't have to resort to rough-house play to win games. Why they had done so this day was beyond me.

Not long after Eric Brook had put us two up, Bertolini hit Eddie Hapgood a savage blow in the face with his elbow as he walked past him. Eddie fell like a Wall Street price in 1929. The next few minutes were dreadful. Tempers flared on both sides, there was a lot of pushing and jostling and punches were exchanged. I abhor such behaviour on the field and when I saw Eddie Hapgood being led off with blood streaming down his face from a broken nose, it sickened me. I'd been really keyed up and looking forward to showing what I could do on the big international scene, but this game was turning into a nightmare.

The game got under way again and the Italians continued where they had left off. It got to a few of our players and I don't mind saying it affected me. Fortunately, we had two real hard nuts in the England side that day in Eric Brook and Wilf Copping who started to dish out as good as they got and more. Wilf was an iron man of a half-back, a Geordie who didn't shave for three days preceding a game because he felt it made him look mean and hard. It did and he was. Eric Brook received a nasty shoulder injury and continued to play manfully with his shoulder strapped up. He was in obvious pain but he just carried on, seemingly ignoring it.

Just before half-time, Wilf Copping hit the Italian captain Monti with a tackle that he seemed to launch from some¬where just north of Leeds. Monti went up in the air like a rocket and down like a bag of hammers and had to leave the field with a splintered bone in his foot. Italy were starting to get the upper hand and laid siege to our goal. It was desperate stuff.

Our dressing room at half-time resembled a field hospital. We were 3-0 up but had paid a bruising price. No one had failed to pick up an injury of one sort of another. The language and comments coming from my England team-mates made my hair stand on end. I was still only 19 but came to the conclusion I'd been leading a sheltered life. I was relieved when our team trainer came into the dressing room, calmed everyone down and said that under no circumstances were we to copy the Italian tactics. We were to go out, he said, and play the way every English team had been taught to play. To do anything but, he said, would exacerbate the situation. Exacerbate the situation? It was already a bloodbath.

(7) Stanley Matthews, The Way It Was (2000)

The game against Germany took on a significance far beyond football. The Nazi propaganda machine saw it as an opportunity to display Third Reich superiority and played up that disconcerting theme big style in the German newspapers. The German team had spent ten days preparing for the game at a special training centre in the Black Forest, whereas after a long and tiresome train journey, we had less than two days to prepare for what we knew was going to be a game of truly epic proportions, a game which to this day is looked upon as the most infamous game England have ever been involved in and all due to one incident.

After all this time, and once and for all, I would like to set the record straight about that incident. As the players were getting changed, an FA official came into our dressing room and informed us that when our national anthem was played, the German team would salute as a mark of respect.

The FA wanted us to reciprocate by giving the raised arm Nazi salute during the playing of the German national anthem. The dressing room erupted. There was bedlam. All the England players were livid and totally opposed to this, myself included. Everyone was shouting at once. Eddie Hapgood, normally a respectful and devoted captain, wagged his finger at the official and told him what he could do with the Nazi salute, which involved putting it where the sun doesn't shine. In fact, Eddie went so far as to offer a compromise, saying we would stand to attention military style but the offer fell on deaf ears.

I sat there crestfallen, thinking what on earth my family and the people back home would think if they saw me and the rest of the England team paying lip service, so to speak, to the Nazi regime and its leaders.

The beleaguered FA official left only to return some minutes later saying he had a direct order from Sir Neville Henderson the British Ambassador in Berlin that had been endorsed by the FA secretary Stanley Rous. We were told that the political situation between Great Britain and Germany was now so sensitive that it needed "only a spark to set Europe alight". Faced with the knowledge of the direst consequences, we felt we had little choice in the matter and reluctantly agreed to the request. However, the game was different. We knew we had it in our power to do something about the match itself and to a man we took the field determined to do so.

All of 110,000 people were crammed into the Olympic Stadium, including Goering and Goebbels, and they roared their approval as the German team took the field. If ever men in the cause of sport felt isolated and so very far from their homes, it was the England team that day in Berlin. The Olympic Stadium was draped in red, black and white swastikas with a large portrait of Hitler above the stand where the Nazi leaders and dignitaries sat. It seemed every supporter on the massed terraces had a smaller version of the swastika and they held them aloft in a silent show of collective defiance as the England team ran out.

During the pre-match kick-in, I went behind our goal to retrieve a wayward ball and an amazing thing happened. As I curled my foot around the ball to steer it back towards the pitch, two lone voices called out, "Let them have it, Stan. Come on England!"

I scanned the sea of faces and the hundreds of swastikas before I saw the most uplifting sight I have ever seen at a football ground. There, right at the front of the terracing, were two Englishmen who had draped a small Union Jack over the perimeter fencing in front of them. Whether they were civil servants from the British Embassy, on holiday or what I don't know, but the brave and uplifting words of those two solitary English supporters among 110,000 Nazis had a profound effect on me and the rest of the England team that day.

When I got back on to the pitch I pointed out the two supporters to our captain Eddie Hapgood and the word spread throughout the team. We all looked across to these two doughty men, who responded by raising the thumbs of their right hands in encouragement. As a team we were immediately galvanised, determined and uplifted by the courage of these two supporters and their small Union Jack Up to that point, I had never given much thought to our national flag. That afternoon however, small as that particular version was, it took on the greatest of symbolism for me and my England team-mates. It seemed to stand for everything we believed in, everything we had left behind in England and wanted to preserve. Above all, it reminded me that we were not after all alone.

The photograph of the England team giving the Nazi salute appeared in newspapers throughout the world the next day to the eternal shame of every player and Britain as a whole. But look closely at the photograph and you will see the German team looking straight ahead but the England players looking off to their left. I can tell you that all our eyes were fixed upon that Union Jack from which we were drawing the inspiration that would carry us to a fantastic and memorable victory.

(8) Eddie Hapgood, Football Ambassador (1945)

The story starts in 1936. That year England competed in the Berlin Olympic Games, held in the fabulous stadium, built for the sole purpose of impressing the world with Nazi might-hundreds of millions of marks were spent, not only in the building, but in propaganda to put over the Games.Mr. Stanley Rous, the Football Association secretary, went over in charge of the English amateur side, which competed in the soccer tournament. Early on, the question of the salute to be given Hitler at the march-past was causing some anxiety. After most of the other countries had decided on the Olympic salute (which is given with the right arm flung sideways, not forward and upward like the Nazi salute), it was arranged that the English athletes should give only the 'eyes right.' Mr. Rous told me afterwards that, to Hitler, and the crowd stepped up in masses round him, the turning of the head by the English team probably passed unnoticed after the outflung arms of the other athletes. So much so that the crowd booed our lads, among them Arsenal colleague, Bernard Joy, and everyone seemed highly offended.When it was our turn to come into the limelight two years later over the same vexed question of the salute, Mr. Wreford Brown, the member in charge of the England team and Mr. Rous, sought guidance from Sir Nevile Henderson, the British Ambassador to Germany, when our party arrived in Berlin. Mr. Rous reminded Sir Nevile of his previous experience and suggested, as an act of courtesy, but what was more important, in order to get the crowd in a good temper, the team should give the salute of Germany before the start. Sir Nevile, vastly relieved at the readiness of the F.A. officials to help him in what must have been an extremely difficult situation, gladly agreed it was the wisest course.Mr. Wreford Brown and Mr. Rous came back from the Embassy, called me in (I was captain) and explained what they thought the team should do. I replied, "We are of the British Empire and I do not see any reason why we should give the Nazi salute; they should understand that we always stand to attention for every National Anthem. We have never done it before-we have always stood to attention, but we will do everything to beat them fairly and squarely." I then went out to see the rest of the players to tell them what was in the offing. There was much muttering in the ranks.When we were all together a few hours before the game, Mr. Wreford Brown informed the lads what I had already passed on. He added that as there were undercurrents of which we knew nothing, and it was virtually out of his hands and a matter for the politicians rather than the sportsmen, it had been agreed that to give the salute was the wisest course. Privately he told us that he and Mr. Rous felt as sick as we did, but that, under the circumstances, it was the correct thing to do.

Well, that was that, and we were all pretty miserable about it. Personally, I felt a fool heiling Hitler, but Mr. Rous's diplomacy worked, for we went out determined to beat the Germans. And after our salute had been received with tremendous enthusiasm, we settled down to do just that. The only humorous thing about the whole affair was that while we gave the salute only one way, the German team gave it to the four corners of the ground.

The sequel came at the dinner in the evening after the game, given by the Reich Association of Physical Exercises, when, with everybody in high good humour, Sir Nevile Henderson whispered to Mr. Rous, " You and the players proved yourselves to be good Ambassadors after all!"

(9) Tommy Lawton, My Twenty Years of Soccer (1955)

Many people have told me that Matthews is slow, but don't be misled by old Shuffling Stan, as we call him. This Prince among wingers looks unconcerned about anything, but watch him when he is showing the ball to an opponent, as if he is counting the panels. Then watch that tremendous burst of speed that takes him clear of everyone.Other people accuse him of being a bad team man, the sort of player who holds up the forward line and allows the defence to get into position. What utter nonsense. Stanley Matthews is a perfectionist, and when he gets the ball he refuses to pass it just for the sake of passing it. He wants his colleagues to move into position, to get away from opponents into the right position for the pass that will bring a goal. If no one moves, Stan will hold the ball until everyone is in position.And no one can hold a ball like Stan. He has uncanny control, and looks quite happy when three or four men are around him.

(10) Stan Mortensen, Football is My Game (1949)

How does he do it? Here are some of the secrets of Stanlev Matthews as I have seen him: Perfect fitness and faithful attention not only to fitness but to playing gear. Superb balance. Complete confidence in his own ability. Tremendous pace over a distance of up to twenty-five yards, but especially over twelve yards, the distance that really matters in football. A beautiful body swerve. Mastery of the ball. He can "kill" it stone dead from all angles and paces. Complete two-footedness. He doesn't mind which foot he has to centre with.

Ideal temperament and self-control. Like all players of this type, he has had to undergo some pretty stiff tackling and fouling, especially from Continental sides. But he never gets rattled, never retaliates (although his father was a professional boxer, and Stan might be expected to be useful with his hands!), never wastes time waving his arms at the referee or arguing with the official. In short, the ideal poker player - on the football field.

(11) Stanley Matthews, The Way It Was (2000)

The England changing room was situated right at the very top of the main stand which meant, after a walk down a tunnel that made Wembley's seem like the lobby of a terraced house, we had to climb about 90 concrete steps before reaching it. We took to that walk as if we were a group of high-spirited lads making our way to the local pub for a night out. We were all in a buoyant and excited mood, but the best was yet to come in the form of what was probably the greatest goal I ever saw in football, courtesy of Len Goulden.In the second half, Alf Young broke down a German attack and played the ball to Charlton's Don Welsh who was making his England debut. We came out of defence with a series of one-touch passes that left the Germans chasing shadows before the ball was finally played out to me on the right. I took off towards Munzenberg, by now run ragged. Such was my confidence that as I ran towards him, I criss-crossed my legs over the ball as I ran and, on reaching him, swept the ball past him with the outside of my right boot and followed it. I could hear Munzenberg and the German left-half panting behind me. I glanced across and saw Len Goulden steaming in just left of the centre of midfield, some 35 yards from goal. I arced around the ball in order to get some power behind the cross and picked my spot just ahead of Len. He met the ball at around knee height. My initial thought was that he'd control it and take it on to get nearer the German goal, but he didn't. Len met the ball on the run; without surrendering any pace, his left leg cocked back like the trigger of a gun, snapped forward and he met the ball full face on the volley. To use modern parlance, his shot was like an Exocet missile. The German goalkeeper may well have seen it coming, but he could do absolutely nothing about it. From 25 yards the ball screamed into the roof of the net with such power that the netting was ripped from two of the pegs by which it was tied to the crossbar. The terraces of the packed Olympic Stadium were as lifeless as a string of dead fish."Let them salute that one," Len yelled as he carried on running, arms aloft.We'd been given little chance, but when the final whistle sounded, the scoreline of Germany 3 England 6 told its own story. As well as myself, the England goals that day came from Robinson (2), Bastin, Broome and Len Goulden's Exocet. It was perhaps the finest England performance I was ever involved in. Every player was at the top of his game, to a man we played out of our skins and Len Goulden's goal will live forever in the memory. If there had been televised football in those days, Len's goal would never have been off the screens. It was truly marvellous.

(12) Cyril Robinson, The Guardian (3rd May 2008)

Joe Smith, the manager, was never very tactical, he was very blunt with his instructions - "Go out there and get them beat," that kind of thing. You can't tell good players like Matthews and Mortensen what to do. We lined up to go on to the field, very quiet. Then as soon as we walk on to the pitch, the roar, it sent shivers down your spine. We line up and are introduced to Prince Philip. We're thinking, let's just get on with the game. We kicked off and within a couple of minutes we had a goal scored against us. That's about the worst thing that could happen. Gradually we got some passes together, got Stan Matthews on the ball and Mortensen got the equaliser, but they went back ahead straight away. Then just after half-time they scored again, 3-1.

(13) Glen Isherwood, Wembley: The Complete Record (2006)

Bolton took a second minute cad when Nat Lofthouse took a pass from Holden and shot from 25 yards. Farm allowed it to slip through his hands into the net. Bolton began to take control, but suffered a blow when Bell went down injured with a pulled muscle. His team mates reshuffled and Bell was moved out to the wing. With ten minutes to go before half-time Blackpool drew level. Hassall, who had dropped back to defence, deflected a Stan Mortensen shot past Hanson. But within five minutes Bolton had regained the lead. When Langton centred, Farm hesitated, and Willie Moir nodded in Bolton's second.Blackpool's world fell apart in the tenth minute of the second half when injured Eric Bell, of all people, rose to head in Holden's centre. Blackpool were 3-1 down, and no team had ever lost a two-goal Iead in all FA Cup final.

(14) Cyril Robinson, The Guardian (3rd May 2008)

It looked hopeless then, I was thinking to myself at least I've been to Wembley. But Morty scored from a Matthews cross to put us back in it and then he equalised direct from a free-kick - I've never seen one taken as well. It flew, you couldn't see the ball on the way to the net. A few minutes from the end I turned to Jackie Mudie and said: "We'll win this in extra-time." But it never got to that - a good move down the right wing, Stan hits the ball along the floor and Bill Perry was in the middle."

(15) Stanley Matthews, The Way It Was (2000)

A minute of injury time remained. What happened then no scriptwriter could have penned because no editor would have accepted a story so far-fetched and outlandish. Ernie Taylor, who had not stopped running throughout the match, picked up a long throw from George Farm, rounded Langton and, as he had done like clockwork through the second half, found me wide on the right. I took off for what I knew would be one final run to the byline. Three Bolton players closed in, I jinked past Ralph Banks and out of the corner of my eye noticed Barrass coming in quick for the kill. They had forced me to the line and it was pure instinct that I pulled the ball back to where experience told me Morty would be. In making the cross I slipped on the greasy turf and, as I fell, my heart and hopes fell also. I looked across and saw that Morty, far from being where I expected him to be, had peeled away to the far post. We could read each other like books. For five years we'd had this understanding. He knew exactly where I d put the ball. Now, in this game of all games, he wasn't there. This was our last chance, what on earth was he doing? Racing up from deep into the space was Bill Perry. "Head over it Bill, don't blast it. Don't blast it!" I said to myself.

I was doing Bill an injustice. The "Original Champagne Perry" was as ice cool as the finest vintage in the coldest of buckets. He coolly and calmly stroked the ball wide of Hanson and Johnny Ball on the goalline and into the corner of the net. From 1-3 down it was now 4-3! Those in the seats took to their feet, those on the terraces and already standing, leapt into the air as Wembley erupted.

Perhaps it was down to the fact I swallowed hard to get some saliva into my dry mouth, or that the sudden eruption of sound was momentarily too much for my eardrums; maybe it was a combination of the two. For a brief moment, although conscious of the pandemonium that had broken out about me, I didn't hear a thing. I watched the ball hit the back of the net, looked back at Bill as he raised his arms and was for a split second rendered totally deaf. I looked at my team-mates jumping for joy and the only noise was a low, droning buzz in my ears. It was as if I was dreaming it. Swallowing hard again, my ears suddenly popped and were immediately assailed by the loudest and most resounding roar I'd ever experienced in a football stadium. It burst from the terraces and roared down and across the pitch like some terrifying banshee.

Having regained my feet, I watched as every player bar George Farm made a beeline for me. Morty's arms were outstretched his face beaming as he sprinted towards me; Bill Perry had an ecstatic smile on his face, his head going from side to side as if in disbelief; Ernie Taylor skipped and jumped as he ran in my direction, punching the air with a fist and yelling `It's there! It's there!' Harry Johnston, who always left his part top set of dentures in a handkerchief in his suit pocket, unashamedly bared his gums to the world. I felt Ewan Fenton's wet and clammy arms across my face as his hands ruffled my hair. It was all I could do to keep my feet as my team-mates mobbed me.

(16) Bill Perry, interviewed by David Millar (1990)

I had to hook it a bit. Morty said he left it to me, but that's not true, it was out of his reach. Ernie Taylor changed the run of play. He didn't get the credit but he was the main man. I'd contributed much more in the semi-final against Spurs. Of course, Stan was special, the ability he had. If a player had a choice of pass, me or Stan, they'd give it to Stan, knowing he'd get to the line and take two opponents with him. For speed I'd beat him every time over 50 yards, but never over five, or 10 yards.

(17) Jimmy Armfield, Right Back to the Beginning (2004)

The club took the whole staff down to Wembley for the day. We travelled on the morning train from Blackpool Central Station, had lunch on the train - unheard of for me - and then walked up Wembley Way. The young players stood on the Spion Kop behind the goal, at the opposite end to where the Blackpool fans had been when the team lost in 1948 and 1951. We knew Blackpool would win - it was fate, destiny, call it what you like - even when we were 3-1 down. With Stanley Matthews around, anything could happen. We were standing at the end where the Blackpool goals went in on the way to that 4-3 victory in what will always be remembered as the Matthews final. Amazing that, when you think that Stan Mortensen became the only player to score a hat-trick in a Wembley FA Cup final. Morty had been suffering from cartilage trouble and he had an operation a few weeks before the game. He had hardly trained, yet he came out and scored a hat-trick.

When the game was over, we rushed back to the station, climbed aboard the train and went home. When we arrived back at around midnight, we discovered that Blackpool had gone crazy. Central Station was awash with tangerine and for the next 48 hours until the players arrived home, the whole town was ecstatic.

(18) Matt Busby, Soccer at the Top (1973)

I had the doubtful pleasure of playing against Stanley Matthews and the real pleasure of playing with him for the combined services. He would come to you with the ball at his dainty feet. He would take you on. You had seen it all before. You knew precisely what he would do and you knew precisely what he would do with you. He would pass you, usually on the outside, but as a novelty on the inside. If you went to tackle him it was merely saving time for him. He then simply beat you. If you didn't he would tease you by coming straight up to you and showing you the ball. And that would be the last you would see of him in that move. If you were covered he would do the same with your cover man and his cover man and so ad infinitum. Then, in his own good time and not before, he would release the perfect pass.

In his moments he would tear a man apart, tear a team apart. He might not be in it for three-quarters of the game. In the other quarter he would destroy you. He wasn't in it in his winning Cup Final for Blackpool against Bolton Wanderers in 1953 for much that mattered until the last phase, during which he destroyed Bolton and laid on the victory. He usually laid everything on for others to finish off. No amount of cover would have stopped him in his magical moments. People were as aware of him as they are of any player today. They set out to stop him as they set out to stop the best today. But the best can't be stopped just by setting people on them.

Stan Matthews was basically a right-footed player, Tom Finney a left-footed player, though Tom's right was as good as most players' better foot. Matthews gave the ball only when he was good and ready and the move was ripe to be finished off. Finney was more of a team player, Matthews being more of an inspiration to a team than a single part of it. Finney was more inclined to join in moves and build them up with colleagues, by giving and taking back. He would beat a man with a pass or with wonderful individual runs that left the opposition in disarray. And Finney would also finish the whole thing off by scoring, which Stan seldom did. Being naturally left-footed, Tom was absolutely devastating on the right wing. An opponent never seemed to be able to get at him. If you were a problem to him he had two solutions to you.

Tom Finney could and would and did play in any forward position. Like Stan Matthews he was never in any trouble with referees. Stan was knighted after his immense period as a player. Tom was awarded the OBE. I do not say that Tom should have played until he was fifty. I do say that I was sorry he did not play for two or three years more than he did, even though he was in his late thirties.

How can anybody say who was the greater ? I think I would choose Matthews for the big occasion - he played as if he was playing the Palladium. I would choose Finney, the lesser showman but still a beautiful sight to see, for the greater impact on his team. For moments of magic - Matthews. For immense versatility - Finney. Coming down to an all-purpose selection about whom I would choose for my side if I could have one or the other I would choose Finney.

(19) Ron Flowers, For Wolves and England (1962)

Looking back upon my international debut, I shall always recall appreciating early in the match with France that a footballer has to forget all he has previously learned in club football. Playing with Stanley Matthews was a case in point. At Wolverhampton I had always been encouraged to hit the ball in front of wingers, but this is very much against Stanley Matthews' way of playing football. He wants you to put the ball at his feet. Then he starts work.

In cold, hard print this may sound a simple thing to do, but in front of 60,000 shouting spectators, and having to make split-second decisions, it can be quite a frightening experience for a young player to have to completely change his approach to the game. In France, I'm afraid, Stanley Matthews did not receive from me the same kind of service he accepted at Blackpool as normal when Harry Johnston was behind him to send forward the passes which Matthews takes for granted...

To watch Stanley Matthews train was a fascinating experience. The most famous forward in the world did not waste his energy aimlessly lapping the track. He concentrated upon twenty-yard bursts, which for acceleration surprised us all. Matthews' secret, apart from his poise, superb fitness, quick-thinking mind, and sheer artistry, is his ability to get himself into top speed long before opponents have even moved.

A remarkable thing about Matthews, however, is that even when training hard he always gives one the impression of having something in reserve. Like all great sportsmen, he has the ability to make everything look so simple.

(20) Nat Lofthouse, Goals Galore (1954)

Stanley Matthews is another very great ball player with whom I've enjoyed playing. But to compare Matthews and Finney is not really possible. They are entirely different in style. Whereas Tom Finney takes the ball no matter how it is sent to him, Stan Matthews prefers it direct to his feet. This, quite naturally, limits a centre-forward's distribution. Stanley does not like a centre-forward to veer out on to his beat, but, as you may have noticed, he frequently draws opponents away from the centre-forward and then pushes over a really "peachy" pass. I am not risking the wrath of millions of his admirers by criticizing Matthews, but I must say that speaking as a centre-forward I prefer the more direct winger. While Stan is beating defenders out on the touch-line, other members of the defence are given valuable time to get back and cover.

As another example of how different in style Matthews and Finney are, I must mention their centres and corner-kicks. Finney, as I remarked earlier, hits the ball over hard and all it needs is a deflection to bring disappointment to a goalkeeper. Matthews' crosses, on the other hand, seem to "float" in the air. Goalkeepers, and other defenders, coming up against this unusual form of centre, are invariably caught in two minds. For the centre-forward, it means a different approach must be made in heading the ball goalwards. With Matthews' centres I have to put my own power behind the ball; in other words, I try to "kick" the ball with my forehead. For speed over 20 yards, too, Stanley Matthews remains the fastest of all wingers. Playing with him has given me memories I shall always cherish.