Stanley Mortensen

Stanley Mortensen was born in South Shields on 26th May 1921. His grandfather was a Norwegian sailor who settled in England. Mortensen's father died when he was five years old and he experienced a great deal of poverty in his childhood.

Mortensen was a keen footballer and was coached by Freddie Colthorpe, the son of his his mother's sister. As he pointed out in his autobiography, Football is My Game: "In our small backyard he spent many hours teaching me the fundamentals of the game; throwing the ball to me for trapping, heading and kicking."

Mortensen began playing for St. Mary's School when he was only nine years old: "The rest of the team were all older boys, up to fourteen, and in addition they were all bigger." In 1934 he was selected to play for the South Shields boy's team representing all the schools in the area. However, he only played in three games before being dropped from the team.

Mortensen left school at 14 and found work in a timber yard on Tyneside. He played football for the South Shields Ex-Schoolboys, a club formed by his former teacher, John Young. He continued to improve as a footballer and in 1937 he was signed by Blackpool. However, over the next couple of years he failed to make a first-team appearance and in April 1939 he was told by manager Joe Smith that he was lucky to be offered another one-year contract.

On the outbreak of the Second World War he joined the Royal Air Force as a wireless-operator air-gunner. Mortensen narrowly escaped death when his Wellington bomber crashed into a forest near Lossiemouth. Mortensen suffered head injuries but the pilot and bomb aimer were killed and the navigator lost a leg. The doctors decided that Mortensen's injuries were so bad that he would never again be fit for operational duties. He was also told that his football career should be brought to an end as heading the ball could cause him serious health problems.

Mortensen was eventually allowed to play football for the RAF. in one game against Leyland Motors he scored four goals in four minutes. This resulted in him being selected for the RAF team that played the British Army. Ted Drake, Raich Carter, Stanley Matthews, Frank Soo, Laurie Scott, George Hardwick and Joe Mercer also played in this game.

The Second World War caused the Football League to be cancelled but Mortensen played in a large number of friendly games for Blackpool. In one game against Burnley he scored four goals. His striking partner, Jock Dodds, added five more.

Mortensen made his league debut at the beginning of the 1946-47 season. That season Blackpool beat Chester (4-0), Colchester United (5-0), Fulham (2-0) to play Tottenham Hotspur in the semi-final at Villa Park. Spurs were leading 1-0 until four minutes from time when Mortensen received a pass from Stanley Matthews. "Then, with the three Spurs men still trying to dispossess me, I hit the ball diagonally across the goal. Luckily I kept it on the ground, and it beat Ditchburn to go into goal just inside the far post." Mortensen scored two more goals in extra-time and therefore reached the final of the FA Cup for the first time.

Blackpool took an early lead in the final at Wembley. Manchester United equalized soon afterwards but Mortensen converted a Hughie Kelly pass to make in 2-1. Mortensen had become the first player in history to score in every round of the FA Cup. However, United came back very strongly in the second-half to win the game 4-2.

Mortensen won his first international cap for England against Portugal on 25th May 1947. It was an amazing debut as he scored four goals in England's 10-0 victory. The England team that day included Stanley Matthews, Tom Finney, Tommy Lawton, Wilf Mannion, Laurie Scott and Frank Swift. That year Mortensen played against Belgium (5-2), Wales (3-0), Northern Ireland (2-2) and Sweden (4-2). In his first five games he scored nine goals.

In the 1950-51 season Blackpool finished in 3rd place in the First Division of the Football League. Mortensen was the division's top scorer with 30 goals. Blackpool beat Stockport County (2-1), Mansfield Town (2-0), Fulham (1-0) and Birmingham City (2-1) to reach the final of the FA Cup. Newcastle United won the game 2-0.

In the 1952-53 season beat Huddersfield Town (1-0), Southampton (2-1), Arsenal (2-1) and Tottenham Hotspur (2-1) to reach the FA Cup final for the third time in five years.

Cyril Robinson claimed that Joe Smith "was never very tactical, he was very blunt with his instructions". According to Stanley Matthews he said: "Go out and enjoy yourselves. Be the players I know you are and we'll be all right." Robinson was later interviewed about the match: "We kicked off and within a couple of minutes we had a goal scored against us. That's about the worst thing that could happen. Gradually we got some passes together, got Stan Matthews on the ball and Mortensen got the equaliser, but they went back ahead straight away."

Stanley Matthews wrote in his autobiography that: "At half-time we sipped our tea and listened to Joe. He wasn't panicking. He didn't rant and rave and he didn't berate anyone. He simply told us to keep playing our normal game." Harry Johnson, the captain, told the defence to "be more compact and tighter as a unit." He also added: "Eddie (Shinwell), Tommy (Garrett), Cyril (Robinson) and me, we will deal with the rough and tumble and win the ball. You lot who can play, do your bit."

Despite the team-talk Bolton Wanderers took a 3-1 lead early in the second-half. Robinson commented: "It looked hopeless then, I was thinking to myself at least I've been to Wembley." Then Stan Mortensen scored from a Stanley Matthews cross. According to Matthews: "although under pressure from two Bolton defenders who contrived to whack him from either side as he slid in, his determination was total and he managed to toe poke the ball off the inside of the post and into the net."

In the 88th minute a Bolton defender conceded a free kick some 20 yards from goal. Stan Mortensen took the kick and according to Robinson: "I've never seen one taken as well. It flew, you couldn't see the ball on the way to the net." Matthews added that "such was the power and accuracy behind Morty's effort, Hanson in the Bolton goal hardly moved a muscle."

The score was now 3-3 and the game was expected to go into extra-time. In his autobiography, Stanley Matthews described what happened next: "A minute of injury time remained... Ernie Taylor, who had not stopped running throughout the match, picked up a long throw from George Farm, rounded Langton and, as he had done like clockwork through the second half, found me wide on the right. I took off for what I knew would be one final run to the byline. Three Bolton players closed in, I jinked past Ralph Banks and out of the corner of my eye noticed Barrass coming in quick for the kill. They had forced me to the line and it was pure instinct that I pulled the ball back to where experience told me Morty would be. In making the cross I slipped on the greasy turf and, as I fell, my heart and hopes fell also. I looked across and saw that Morty, far from being where I expected him to be, had peeled away to the far post. We could read each other like books. For five years we'd had this understanding. He knew exactly where I d put the ball. Now, in this game of all games, he wasn't there. This was our last chance, what on earth was he doing? Racing up from deep into the space was Bill Perry."

Stanley Matthews added that Perry "coolly and calmly stroked the ball wide of Hanson and Johnny Ball on the goalline and into the corner of the net." Bill Perry admitted: "I had to hook it a bit. Morty said he left it to me, but that's not true, it was out of his reach." Blackpool had beaten Bolton Wanderers 4-3.

As Jimmy Armfield pointed out: "We were standing at the end where the Blackpool goals went in on the way to that 4-3 victory in what will always be remembered as the Matthews final. Amazing that, when you think that Stan Mortensen became the only player to score a hat-trick in a Wembley FA Cup final. Morty had been suffering from cartilage trouble and he had an operation a few weeks before the game. He had hardly trained, yet he came out and scored a hat-trick." Interestingly, Stanley Matthews always insisted that he was overpraised for his performance that day and in his autobiography, The Way It Was, he called it the "Mortensen Final".

Tommy Lawton described Mortensen as "the most dangerous attacker of his day". He added: "With that curious, energetic run he has burst open more defences than any other man of his time, and I don't think I know a player who was faster off the mark than this Blackpool Bombshell was. Knocks and injuries meant nothing to Morty."

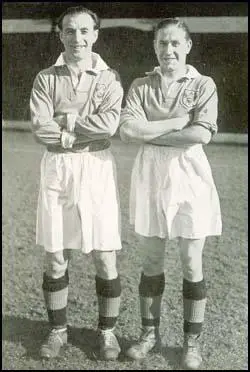

Mortensen developed a great partnership with Stanley Matthews. He later wrote: "With the passing of each game, we developed a greater understanding of one another's style of play. A couple of years down the line it was as if we could read one another's minds. The on-the-field relationship was uncanny. When such a partnership is formed in football, it produces magical moments."

In his autobiography, The Way It Was, Matthews argued: "For a forward renowned for his goalscoring, he would often drop off quite deep to collect the ball and once he had it I'd take off down the wing. Invariably I'd never look back, the ball would be pushed in front of me to run on to, or come looping over my shoulder beautifully weighted with back spin on it so it slowed up ready for me to collect without breaking stride. Morty would head off for the left of the penalty spot, then with a burst of lightning speed head towards the near post. His change in direction and speed threw defenders and more often than not it meant he arrived at the near post in space. He wasn't the tallest of forwards and this I think helped him in his ability to swivel and turn his body for the arriving ball. He was lethal in the box and pretty lethal outside it as well. He possessed a monstrous and explosive shot with either foot. For a man of his height, five feet ten, he was a match for anyone in the air. He had the uncanny knack of all great predatory strikers of being able to predict where the ball would arrive and this meant he often met it without having an aerial duel with the towering centre-half whose job it was to mark him. Once airborne, it was as if the thumb and first finger of the right hand of the good Lord had reached down, nipped the shirt on his back and held him there because Morty seemed to defy gravity and hang in the air for ages."

Stan Mortensen won his last international cap for England against Hungary on 25th November, 1953. England lost the game 6-3. Mortensen had the great record of scoring 23 goals in 25 games but a series of injuries knee restricted his club appearances.

In 1955 Mortensen joined Hull City in the Second Division. While at Blackpool he had scored 197 goals in 317 appearances. Mortensen was unable to stop Hull being relegated to the Third Division in the 1955-56 season. He also played for Southport (1957-58), Bath City (1958-59) and Lancaster City (1960-61).

Mortensen was appointed manager of Blackpool in 1967. The club had just been relegated to the Second Division. Blackpool finished 3rd in the 1967-68 season but after dropping to 8th in the 1968-69 season he was sacked.

Stanley Mortensen died on 22nd May, 1991. The funeral was held at St John's parish church in Blackpool. One journalist commented that, "I suppose they'll call it the Matthews funeral".

Primary Sources

(1) Stanley Mortensen, Football is My Game (1949)

My father died when I was five, and my mother was left with two boys to bring up. I need not say that the task was one which promised only a future of hard work, with the end of the road a long distance away. Without boasting, I think I can say that the two of us determined to do our best; and I daresay that deep-thinking psychologists and psychiatrists may be able to find in my method of play some connection with those early struggling days when the two Mortensen boys, young as they were, realised that they would have to make their own way in the world.

When other boys were dreaming of becoming engine-drivers, soldiers, explorers, and so on, I was thinking of something that was actually within my compass - football. Looking back now, I cannot remember any time when I was not certain that one day, somewhere, I would earn my living on the football field...

Football filled my every waking hour. At St. Mary's school, South Shields, I spent every moment of my spare time playing football. There were some stolen moments, too, when I should have been engaged on what my teachers would have described as more important things.

I suppose I must have been pretty good for my age, because after a period at inside-right I was moved to centre-half. In school teams it is the best footballer who is placed at centre-half. In such sides, the pivot is still an attacker, not a stopper as in more advanced football, and a player is required who can do useful work up-field-and also get back. The centre-half position was also considered the most difficult. Some people think that in modern top football the centre-half has a money-for-jam job. It isn't quite that; and, in any case, in junior football, it isn't a bad idea for a boy to have a go at centre-half and to regard it as a position in which he has to be the complete footballer...

When I first played in the team of St. Mary's School, Tyne Dock, South Shields, I was only nine. The rest of the team were all older boys, up to fourteen, and in addition they were all bigger. I was never very tall, and at nine years of age I was pretty skinny, too. We played in a school league, and I am afraid we were usually somewhere near the wrong end of the table...

Mr. Young re-formed an old club known as St. Andrews, and called it South Shields Ex-Schoolboys Club... We had the advantage of having played together at school and were all pals, so we soon became a pretty hot combination. We were too good for anything else in the district of the same age, and we won all sorts of prizes.

I was lucky to be in such a team, and to be able to play regularly, for it is in the fourteen to sixteen years period that many boys cannot find opportunities for serious football, and lose interest in the game. Shortage of pitches, lack of organised facilities, and the necessity for working for a living are all contributory factors to this state of affairs.

(2) Stanley Mortensen, Football is My Game (1949)

In recent years there has been a good deal of controversy about coaching. The Football Associa¬tion have been encouraging the development of a coaching system, but from time to time I have heard criticism of their policy. Was this or that great player ever coached? Didn't the best players learn their own football on waste ground and by hard experience? And so on.

It may be true that some of the finest players who ever donned boots never took part in organised football lessons, but I believe that if we could probe their lives, we would find that every great footballer had some lessons in his early days. No matter how gifted a boy may be, it is in my opinion important for him to come under some sort of guidance as soon as possible. But the coach must be a fellow who knows : who can develop the natural ability and guide the young player into the right channels.

In my case, the coach was one of the family, a cousin named Freddie Colthorpe. He was the son of my mother's sister, and was as keen about football as his younger cousins. He was not particularly outstanding as a player, but he was secretary of Tyne Dock United team, and he seems to have made up his mind, as soon as I showed some aptitude for the game, that I should be put on the right lines.

I am glad now to pay tribute to the patient care of Freddie Colthorpe. In our small backyard he spent many hours teaching me the fundamentals of the game ; throwing the ball to me for trapping, heading and kicking.

Once I had been grounded in these things, the rest came naturally to me. What I would have done, or become, without that friendly coaching of my cousin, I do not know. Not such a good footballer, I am certain. So when you hear of coaching schemes, don't scoff. They are for the young footballers who were not as fortunate as I.

(3) Stanley Mortensen, Football is My Game (1949)

During my time in the R.A.F. I was pushed around the country in the fashion only too familiar to millions of men... The football I played during the war period was important. This was the time when I began to play alongside recognised internationals, and was myself, in turn, spotted by selectors of various representative teams.

I was sent to Padgate in Lancashire; then home again; then to Blackpool, where forty thousand other R.A.F. types were training ; thence to Compton Bassett in Wiltshire; back to Blackpool; Yatesbury in Wiltshire; Walney Island; Lossiemouth; Eastchurch; Blackpool; Chigwell; and London.

It was while I was at Lossiemouth that I met with the accident which nipped my "career" as a wireless-operator air-gunner in the bud, and prevented me from being sent abroad.

We were on operational training; the Wellington caught fire, and down we went in a dive. We finished in a fir-plantation, the pilot and bomb-aimer were killed, the navigator lost a leg, and I got out alive with various injuries of which the worst was a head wound which called for a dozen stitches.

The doctors decided that my injuries were such that I would never again be fit for operational duties, and naturally enough I wondered about my football career. Should I ever be able to head a ball again? If not, I was finished, because heading the ball is half of my game.

(4) Stanley Mortensen, Football is My Game (1949)

Early in the following season came the first of the Victory internationals. They were full representative games in everything but name, with each country able to choose practically from its full strength. The opening one of these fixtures was at Windsor Park, Belfast, and early in September I was overjoyed to find myself selected. Stan Matthews and Raich Carter formed the right-wing again, the new left-wing pairing being myself and Leslie Smith, with Tommy Lawton in the middle.

This game brought me to full realisation of the genius of Peter Doherty, my opposite number. At the time Peter was very unsettled, because he had practically decided not to resume his old association with Manchester City, but this did not affect his football. There was scarcely a blade of grass he did not cover in the course of a game in which England attacked almost constantly but were held up by a fine defence in which Peter took his full share. Centre-half Vernon, too, was in magnificent shape, and gave many people their first indication that he was to become one of the great " stoppers " of post-war football.

Some of the first-time tackling, although fair enough, could only have been accomplished by an Irish side playing before their own supporters, and for eighty minutes we hammered away without being able to put the ball into the net.

With ten minutes to go, Stan Matthews secured possession, beat one man, drew another, and centred. I was able to run on to it in the manner footballers like best. I took it in my stride, the ball running perfectly for me, and into the net it sailed. Once again I had been fortunate enough to score the winning goal for England.

(5) Stanley Mortensen, Football is My Game (1949)

I cried after the Cup Final of 1948... but it wasn't because I had been on the losing side at Wembley. We had lost the last great round ; had failed to win the Cup, yet I walked off that marvellous pitch in that wonderful stadium with tears of real happiness in my eyes.

The picture will remain with me while memory lasts. The game was over, the medals had been presented to both sides, and the Cup itself to Johnny Carey, the Manchester United captain. The Black¬pool players had stood in a group, talking of this and that, while the victorious team walked up to the Royal Box to receive their mementoes and handshakes from the King and Queen. Then our turn had come, and we had filed past the Royal Family with their warm smiles, their words of sympathy for the losers coming just as sincerely as their earlier words of congratulation for the winners.

In accordance with tradition, the United players had chaired their captain off the pitch, all the way to the dressing-room.

We Blackpool players walked off slowly behind our victors. We had lost-lost after twice leading, a record of its kind at Wembley - yet I don't think we were too dispirited. Sorry, yes, but still excited from the heat of the struggle, with our thoughts in a tangle.

We walked off the turf, on to the track which surrounds the finest playing pitch in the British Isles. I happened to glance up to the crowd, loath to go away, staying on to see the curtain rung down on the drama of the Cup Final.

There, standing over the tunnels which led to the dressing-rooms, was a party of Blackpool supporters. Beribboned and bedecked in our famous tangerine, with caps, streamers, rosettes, scarves, ail telling of their loyal support for the Bloomfield Road club, they stood, silently surveying the last moments of the last incidents of a memorable day.

In the spring sunshine I could see almost every individual plainly. They stood there, mute in their disappointment, gazing down as their favourite team walked off-without the Cup which they had hoped we would carry back to the seaside.

Their silent sympathy with us, their regret at the result, was obvious ; and across the intervening space, from crowd to players, there seemed some link, some bond of fellowship. Hardly thinking what I was doing, I waved to that silent crowd.

The effect was magical. They responded with a shout which seemed as mighty as anything we had heard during the pulsating struggle of the match itself. With a thunderous roar they let loose all their hot fanaticism for us and for the game of soccer.

I thought, as though in a dream lasting only a second or two, of the path to Wembley: how the Blackpool team had been reshaped after the war, how we had started this one great season with such high hopes ; how we had won first one game and then another; how we had knocked out the giant-killing Colchester United ; how we had gone to the semi-final against Tottenham Hotspur ; how we had struggled against an unlucky one-goal deficit; how we had won equality in the last minutes of the match; how we had scored two more in extra time to earn the match at Wembley.

I thought of the scramble for tickets; and I thought, too, of the patience and keenness of those cheering supporters, many of whom had travelled all through the night to get to Wembley. And above all, I thought of the greatness of a game that could develop such sportsmanship, such warm support, such loyalty, and, at the end of a losing match, such spontaneous comradeship with the beaten team.

All these thoughts flashed through my mind as I walked those last few yards to the darkness under the Wembley terraces. As I passed from the view of the cheering throng, I waved again. They could still see me, but I could not see them. My eyes were filled with tears.

(6) Cyril Robinson , The Guardian (3rd May 2008)

It looked hopeless then, I was thinking to myself at least I've been to Wembley. But Morty scored from a Matthews cross to put us back in it and then he equalised direct from a free-kick - I've never seen one taken as well. It flew, you couldn't see the ball on the way to the net. A few minutes from the end I turned to Jackie Mudie and said: "We'll win this in extra-time." But it never got to that - a good move down the right wing, Stan hits the ball along the floor and Bill Perry was in the middle."

(7) Stanley Matthews , The Way It Was (2000)

A minute of injury time remained. What happened then no scriptwriter could have penned because no editor would have accepted a story so far-fetched and outlandish. Ernie Taylor, who had not stopped running throughout the match, picked up a long throw from George Farm, rounded Langton and, as he had done like clockwork through the second half, found me wide on the right. I took off for what I knew would be one final run to the byline. Three Bolton players closed in, I jinked past Ralph Banks and out of the corner of my eye noticed Barrass coming in quick for the kill. They had forced me to the line and it was pure instinct that I pulled the ball back to where experience told me Morty would be. In making the cross I slipped on the greasy turf and, as I fell, my heart and hopes fell also. I looked across and saw that Morty, far from being where I expected him to be, had peeled away to the far post. We could read each other like books. For five years we'd had this understanding. He knew exactly where I d put the ball. Now, in this game of all games, he wasn't there. This was our last chance, what on earth was he doing? Racing up from deep into the space was Bill Perry. "Head over it Bill, don't blast it. Don't blast it!" I said to myself.

I was doing Bill an injustice. The "Original Champagne Perry" was as ice cool as the finest vintage in the coldest of buckets. He coolly and calmly stroked the ball wide of Hanson and Johnny Ball on the goalline and into the corner of the net. From 1-3 down it was now 4-3! Those in the seats took to their feet, those on the terraces and already standing, leapt into the air as Wembley erupted.

Perhaps it was down to the fact I swallowed hard to get some saliva into my dry mouth, or that the sudden eruption of sound was momentarily too much for my eardrums; maybe it was a combination of the two. For a brief moment, although conscious of the pandemonium that had broken out about me, I didn't hear a thing. I watched the ball hit the back of the net, looked back at Bill as he raised his arms and was for a split second rendered totally deaf. I looked at my team-mates jumping for joy and the only noise was a low, droning buzz in my ears. It was as if I was dreaming it. Swallowing hard again, my ears suddenly popped and were immediately assailed by the loudest and most resounding roar I'd ever experienced in a football stadium. It burst from the terraces and roared down and across the pitch like some terrifying banshee.

Having regained my feet, I watched as every player bar George Farm made a beeline for me. Morty's arms were outstretched his face beaming as he sprinted towards me; Bill Perry had an ecstatic smile on his face, his head going from side to side as if in disbelief; Ernie Taylor skipped and jumped as he ran in my direction, punching the air with a fist and yelling `It's there! It's there!' Harry Johnston, who always left his part top set of dentures in a handkerchief in his suit pocket, unashamedly bared his gums to the world. I felt Ewan Fenton's wet and clammy arms across my face as his hands ruffled my hair. It was all I could do to keep my feet as my team-mates mobbed me.

(8) Bill Perry, interviewed by David Millar (1990)

I had to hook it a bit. Morty said he left it to me, but that's not true, it was out of his reach. Ernie Taylor changed the run of play. He didn't get the credit but he was the main man. I'd contributed much more in the semi-final against Spurs. Of course, Stan was special, the ability he had. If a player had a choice of pass, me or Stan, they'd give it to Stan, knowing he'd get to the line and take two opponents with him. For speed I'd beat him every time over 50 yards, but never over five, or 10 yards.

(9) Jimmy Armfield, Right Back to the Beginning (2004)

The club took the whole staff down to Wembley for the day. We travelled on the morning train from Blackpool Central Station, had lunch on the train - unheard of for me - and then walked up Wembley Way. The young players stood on the Spion Kop behind the goal, at the opposite end to where the Blackpool fans had been when the team lost in 1948 and 1951. We knew Blackpool would win - it was fate, destiny, call it what you like - even when we were 3-1 down. With Stanley Matthews around, anything could happen. We were standing at the end where the Blackpool goals went in on the way to that 4-3 victory in what will always be remembered as the Matthews final. Amazing that, when you think that Stan Mortensen became the only player to score a hat-trick in a Wembley FA Cup final. Morty had been suffering from cartilage trouble and he had an operation a few weeks before the game. He had hardly trained, yet he came out and scored a hat-trick.

When the game was over, we rushed back to the station, climbed aboard the train and went home. When we arrived back at around midnight, we discovered that Blackpool had gone crazy. Central Station was awash with tangerine and for the next 48 hours until the players arrived home, the whole town was ecstatic.

(10) Tommy Lawton, My Twenty Years of Soccer (1955)

I have never been able to work out whether Stanley Mortensen was a centre forward or an inside man. Whatever he was, he was just about the most dangerous attacker of his day.

Stan, just about the only player of Norwegian ancestry, came from the North East, where they breed some great footballers, and during the war he was the only survivor of an air crash. He was then an air gunner in the R.A.F., and few people gave him much chance of making the big time in soccer after that.

But spring-heeled Morty had the heart of a pack of lions. With that curious, energetic run he has burst open more defences than any other man of his time, and I don't think I know a player who was faster off the mark than this Blackpool Bombshell was. Knocks and injuries meant nothing to Morty, and I am sure that Blackpool supporters will talk for years about that wonderful trio which used to form the right wing at Bloomfield Road - Harry Johnston, Stanley Matthews, and Stan Mortensen.

(11) Stanley Matthews, The Way It Was (2000)

With some people you meet there is an immediate chemistry and you bond straightaway. With others, although you have dealings with them every day and get on perfectly well, there is nothing. With Stan Mortensen and me, the former was true. With the passing of each game, we developed a greater understanding of one another's style of play. A couple of years down the line it was as if we could read one another's minds. The on-the-field relationship was uncanny. When such a partnership is formed in football, it produces magical moments.

Later, he kindly said that his career blossomed through his on-the-pitch relationship with me. In teaming up with Morty the same can be said of my game. Whether in the shirts of Blackpool or England, we worked it the same. Wherever I was on the wing I knew where Morty would be in the middle. For a forward renowned for his goalscoring, he would often drop off quite deep to collect the ball and once he had it I'd take off down the wing. Invariably I'd never look back, the ball would be pushed in front of me to run on to, or come looping over my shoulder beautifully weighted with back spin on it so it slowed up ready for me to collect without breaking stride. Morty would head off for the left of the penalty spot, then with a burst of lightning speed head towards the near post. His change in direction and speed threw defenders and more often than not it meant he arrived at the near post in space. He wasn't the tallest of forwards and this I think helped him in his ability to swivel and turn his body for the arriving ball. He was lethal in the box and pretty lethal outside it as well. He possessed a monstrous and explosive shot with either foot. For a man of his height, five feet ten, he was a match for anyone in the air. He had the uncanny knack of all great predatory strikers of being able to predict where the ball would arrive and this meant he often met it without having an aerial duel with the towering centre-half whose job it was to mark him. Once airborne, it was as if the thumb and first finger of the right hand of the good Lord had reached down, nipped the shirt on his back and held him there because Morty seemed to defy gravity and hang in the air for ages. Denis Law in his heyday with Manchester United in the sixties is the only other player I've seen do that. Morty could despatch headers like bullets from a gun and for all he wasn't the biggest of forwards, his beer barrel chest, cornflake box shoulders and legs like bags of concrete made him a formidable opponent for the toughest of defenders. I can't ever recall him being knocked off the ball and when he went after it, he did so with demonic enthusiasm.

There were some tough centre-halves about at this time - Bill Shorthouse of Wolves, Allenby Chilton at Manchester United, "Whacker" Hughes of Liverpool, Newcastle's Frank Brennan, Joe Kennedy of West Brom and, lest we forget, on the international front, Scotland's Willie Woodburn, a player whose exploits ended with him being banned sine die. Morty got stuck into them all and they into him! "If blood be the price of Admiralty, Lord God we have paid in full," wrote Kipling. Morty was a class act but if blood and bruises can be construed as a necessary part of winning games, then Stan Mortensen's account was paid up in full. Not once did I hear him complain about his lot. "All part of the game, though happily the larger part is played out with the artist's brush," he used to say and how right he was. For all he was a man of great physical strength and fortitude, more often than not his contribution to the canvas of a game had all the delicacy and elegance of a painting by Renoir.