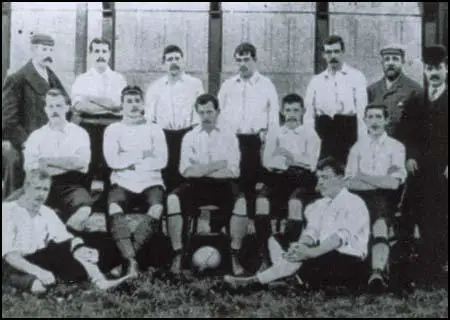

Bolton Wanderers : 1874-1950

In 1874 the Reverend John Farrall Wright and schoolmaster Thomas Ogden established the Christ Church Sunday School football team. The team, captained by Ogden, played at the Park Recreation Ground. In 1877 there was a dispute between Wright and Ogden and as a result a new team, Bolton Wanderers, was formed. They now played their games at Pikes Lane.

Bolton Wanderers entered the FA Cup for the first time in the 1881-82 season. They lost 6-2 to Blackburn Rovers in the second round of the competition. The following year they beat Liverpool Ramblers 3-0 but lost in the next round to the Druids. In 1883 Bolton started the competition with a 8-1 victory over Irwell Springs. They were drawn against the powerful Notts County in the 4th round. The game ended in a 2-2 draw but Bolton lost the replay 2-1.

In January, 1884, Preston North End played the London side, Upton Park, in the FA Cup. After the game Upton Park complained to the Football Association that Preston was a professional, rather than an amateur team. Major William Sudell, the secretary/manager of Preston admitted that his players were being paid but argued that this was common practice and did not breach regulations. However, the FA disagreed and expelled them from the competition. Sudell had improved the quality of the team by importing top players from other areas. This included several players from Scotland. As well as paying them money for playing for the team, Sudell also found them highly paid work in Preston.

Preston North End now joined forces with other clubs who were paying their players, such as Bolton Wanderers, Aston Villa and Sunderland. In October, 1884, these clubs threatened to form a break-away British Football Association. The Football Association responded by establishing a sub-committee, which included William Sudell, to look into this issue.

In February 1885 John J. Bentley was appointed secretary of Bolton Wanderers. Bentley was an advocate of professionalism and he began recruiting talented players and paying them a match fee. On 20th July, 1885, the FA announced that it was "in the interests of Association Football, to legalise the employment of professional football players, but only under certain restrictions". Clubs were allowed to pay players provided that they had either been born or had lived for two years within a six-mile radius of the ground.

The decision to pay players increased club's wage bills. It was therefore necessary to arrange more matches that could be played in front of large crowds. On 2nd March, 1888, William McGregor circulated a letter to Bolton Wanderers, Aston Villa, Blackburn Rovers, Preston North End, and West Bromwich Albion suggesting that "ten or twelve of the most prominent clubs in England combine to arrange home and away fixtures each season."

John J. Bentley of Bolton Wanderers and Tom Mitchell of Blackburn Rovers responded very positively to the suggestion. They suggested that other clubs should be invited to the meeting being held on 23rd March, 1888. This included Accrington, Burnley, Derby County, Notts County, Stoke, Wolverhampton Wanderers, Old Carthusians, and Everton should be invited to the meeting.

The following month the Football League was formed. It consisted of six clubs from Lancashire ( Bolton Wanderers, Preston North End, Accrington, Blackburn Rovers, Burnley and Everton) and six from the Midlands (Aston Villa, Derby County, Notts County, Stoke, West Bromwich Albion and Wolverhampton Wanderers). The main reason Sunderland was excluded was because the other clubs in the league objected to the costs of travelling to the North-East. McGregor also wanted to restrict the league to twelve clubs. Therefore, the applications of Sheffield Wednesday, Nottingham Forest, Darwen and Bootle were rejected.

The first season of the Football League began in September, 1888. Preston North End won the first championship without losing a single match and acquired the name the "invincibles". Bolton Wanderers finished in 5th place, winning 10 of their 22 games.

John J. Bentley began recruiting players such as James Turner, John Somerville, Di Jones, John Sutcliffe and James Cassidy. However, in the 1889-90 season Bolton finished 9th with 19 points out of a possible 44. The 1890-91 season saw a slight improvement with the club finishing in 5th place with 25 points. The following season they finished in 3rd place obtaining 36 points in 26 games.

In the 1893-94 season, Bolton beat Small Heath (4-3), Newcastle United (2-1), Liverpool (3-0) and Sheffield Wednesday (3-2) to reach the 1894 FA Cup Final. Unfortunately, Bolton lost to Notts County 4-1 in the final at Goodison Park.

In 1895 Bolton Wanderers moved to the Burnden Park ground. It became the club's stadium for the next 102 years. It was also used for the replay of the 1902 FA Cup Final between Tottenham Hotspur and Sheffield United.

James Cassidy was the star of the team during this period. He played for Bolton for eight seasons. He was the club's top scorer in five seasons and overall he scored 101 goals in 219 games. John Sutcliffe, the Bolton goalkeeper, also won five international caps for England during his time at the club.

In April 1895 Bolton Wanderers played an away game against Bury in the Lancashire Senior Cup. After James Turner made a strong tackle against an opponent the home crowd rushed on the field and attacked him and the referee was forced to abandon the game.

Bolton Wanderers finished 10th (1894-95), 4th (1895-96), 8th (1896-97) and 11th (1897-98). In 1898 season John Somerville was employed as Bolton's player-manager. Unfortunately, in his first season in charge the club finished 17th and was relegated to the Second Division.

In 1899-1900 Bolton finished second to Sheffield Wednesday and returned to the First Division. Laurie Bell was top scorer that season with 23 goals. The club continued to struggle in the top tier and in the 1902-03 season they finished bottom and was once again relegated.

Bolton kept faith with John Somerville and in the 1904-05 season the club finished second to Liverpool and was promoted back to the First Division. Bolton had two good seasons where they finished 6th before being relegated again in the 1907-08 season. Bolton bounced back by winning the Second Division championship in the 1908-09 season.

Once again Bolton struggled in the top tier and in January 1910, with the club firmly entrenched at the bottom of the First Division, John Somerville was sacked and replaced by Will Settle. He was unable to save the club from relegation but he steered Bolton to promotion at the first attempt. Settle also recruited a group of talented players including Ted Vizard, Joe Smith and Jimmy Seddon.

In 1911-12 Bolton finished fourth in the First Division and in the 1914-15 they reached the semi-final of the FA Cup. However, they were beaten 2-1 by Sheffield United. At the end of the season professional football in Britain came to an end because of the First World War. In 1915 Will Settle left the club to be replaced by Tom Mather. According to Dean Hayes, the author of Bolton Wanderers (1999): "After finding certain responsibilities had been taken away from him, he left the club under something of a cloud after 17 years' service." Soon afterwards Mather was called up to join the Royal Navy and his assistant, Charles Foweraker, became the new manager.

After the war, Charles Foweraker, built an outstanding team that included Joe Smith, Billy Jennings, Jimmy Seddon, John Reid Smith, David Jack, Billy Butler, Walter Rowley, Ted Vizard, Harry Nuttall, Dick Pym, Alex Finney and Bob Haworth.

In the 1920-21 season Bolton Wanderers finished in 3rd place in the First Division of the Football League. Joe Smith, scored a club record of 38 goals, this included hat-tricks against Middlesbrough, Sunderland and Newcastle United.

Bolton Wanderers enjoyed a good FA Cup run in the 1922-23 season. They beat Leeds United (3-1), Huddersfield Town (1-0), Charlton Athletic (1-0) and Sheffield United (1-0) to reach the first cup final to be held at Wembley Stadium.

David Jack, Ted Vizard, Harry Nuttall, John Reid Smith, Bob Haworth, Billy Butler & Joe Smith.

The Empire Stadium had a capacity of 125,000 and so the Football Association did not consider making it an all-ticket match. After all, both teams only had an average attendance of around 20,000 for league games. However, it was rare for a club from London to make the final of the FA Cup and supporters of other clubs in the city saw it as a North v South game.

The Bolton Evening News reported: "It is computed that fully 250,000 people made their way to the imposing and spacious ground form all parts of the Empire, all anxious to see the blue riband of the football world decided. About 60,000 people had passed inside the turnstiles when pandemonium broke loose. One of the main exits was broken down and thousands of people surged inside the enclosure, and from that moment the situation showed signs of getting out of hand. People scaled high walls and clambered into seats for which others had paid. Such was the pressure on the ringside fences that they gave way. The crowd rushed across the large cinder track which encircles the playing pitch, and in an incredibly short time the beautiful greensward was occupied by a black uncontrollable mass. The police, apparently taken by surprise, were for a time powerless to deal with the situation and even after more officers, mounted and on foot, had been rushed to the ground, the task of clearing the playing pitch was a tediously slow process."

At 1.45 pm instructions were given for all gates to be closed. George Kerr later commented: "I saw the turnstiles had been built into woodern structures that were about 8 feet high, the turnstiles themselves were locked and deserted but bodies were climbing over them like monkeys and I quickly followed suit... I got behind the crowd and soon was being pushed forward by others who got behind me. I was literally pushed into the ground."

A reporter from the East Ham Echo described the scene after the gates were closed: "Something unusual was happening. Then the word went round that the disappointed multitude at the gates had broken through. They streamed down the little tributaries in a vast sea of heads, and settled on the cinder track round the pitch. Then came a sudden movement of the front ranks - a rush, the thin cordon of police and stewards was brushed aside like a cobweb, and in a moment the playing pitch, which had drawn the gaze for so long, brightly verdant in the sunshine, was blotted out - black with a restless, moving, excited throng of people. Football was forgotten. Spectators, who had taken up and held their positions since early morning, were bundled unceremoniously out of place by the rush, and swept on to the green. Everywhere men and women were seen clambering over the low rails and partitions, eager to secure seats in the stands. Strong men and frail women fainted and fell in the crush and excitement, and the ambulance brigade were hotly engaged in dealing with casualties which increased every minute."

Albert York was a barrow-boy who sold apples and pears to fans going to the game: "When everything was sold we went into the match through a broken gate and joined the heaving, sweating cloth-capped mass of humanity, but hardly saw a thing of the action because of the immense crowd."

crowd from the pitch before the 1923 FA Cup Final.

According to The Times newspaper, about a 1,000 people were injured attempting to get into Wembley Stadium that day. The spectators at the front were pushed onto the field making it impossible for the game to get started. For a while it seemed that the game would have to be postponed. However, in the words of one East Ham Echo reporter, "...then came the miracle. Half a dozen mounted policeman arrived on the scene, and working from the centre of the pitch by great efforts, filched a little more space from the crowd, which the cordon of police endeavoured to hold.... But wonders of wonders was the work of an inspector on a dashing white horse." The inspector on the white horse was G. A. Story and as a result of these efforts the game began after a 40 minute delay.

Jimmy Ruffell was later interviewed about the game: "Most of the people at Wembley seemed to be Londoners. Well, the ones I saw seemed to be. As we tried to make our way out onto the field everyone was slapping us on the back and grabbing our hands to shake them. By the time I got to the centre of the pitch my poor shoulder was aching."

West Ham trainer, Charlie Paynter, complained: "When the players of both sides got on the pitch there seemed quite a hundred London supporters to every Bolton supporter. My boys were slapped and pulled about, while the Bolton players got through practically unscathed. Unfortunately Ruffell, who had just got over an injured shoulder, which was naturally tender; and Tresadern both received severe shakings before they reached the pitch... It was a pitch made for us until folks tramped all over the place. when the game started it was hopeless. Our wingers, Ruffell and Richards were tripping in great ruts and holes... The pitch had been torn up badly by the crowd and the horses wandering over it."

The game eventually started 43 minutes late. In the second minute Jack Tresadern got stuck in the crowd after going in to retrieve the ball for a throw in. Before he could get back onto the field, the ball was sent into the West Ham United penalty area. Jack Young gained possession of the ball but he gave it away to Jimmy Seddon. The ball was then passed to David Jack. According to The Times reporter at the game: "Jack feinted to pass out to Butler; when the pass looked as good as made, he dribbled inside to the left, went through the West Ham United defence at a great pace and scored from close in with a hard high shot into the right-hand corner of the net."

Three minutes later, Dick Pym, the Bolton goalkeeper, missed a corner-kick from Jimmy Ruffell and the usually reliable Vic Watson, blasted the ball over the crossbar. The Times journalist covering the game wrote: "Pym, misjudging a perfectly taken corner by Ruffell, came out of goal and missed the ball. The ball came to Watson, who had an open goal yawning only a few yards in front of him. How he managed to kick the ball over the cross-bar instead of into the net one cannot imagine; if a player tried to do it, the odds against him would be generous. Watson, however, did fail to score."

Soon afterwards West Ham United had another chance when Dick Richards finished off a brilliant dribble with a clever shot that Dick Pym managed to save. After 13 minutes the game was brought to a halt after the crowd spilled on to the pitch in front of the main stand. It was another ten minutes before the mounted police cleared the pitch and the match could resume.

Once the game had restarted Joe Smith appeared to scored from a clever centre from Billy Butler but was ruled offside. Bolton were the better team in the first-half and the East Ham Echo reported that this was "because they were more experienced and better fitted temperamentally to stand the strains of the extraordinary conditions."

The teams did not leave the field at half-time but crossed over and resumed play after a five-rninutes' interval. West Ham United began the second half well and Vic Watson just failed to convert a cross from George Kay. This was followed by another near miss. According to George Kerr: "It was a hard low cross from Richards on the right wing arriving about chest-high outside the six-yard box. Watson went for it and had he contacted he must have scored but Pym, the goalie, managed to get his hand to it, knocking it down and collecting it."

In the 54th minute Joe Smith received a pass from Ted Vizard and volleyed against the underside of the bar. The referee ruled that it had crossed the line, before rebounding back into play. Bolton Wanderers now had a two-goal lead.

West Ham United continued to press forward but failed to make anymore chances. The Daily Mirror reported: "The prescence of the crowd on the touchlines considerably hampered the work of the wingers." Jimmy Ruffell later admitted: "It was a hard game for West Ham to play as the field had been churned up so bad by horses and the crowd that had been on the pitch well before the game. West Ham made a lot of the wings and you just couldn't run them for the crowd that were right up close to the line."

George Kerr supported this view: "The conditions did not suit West Ham. They relied heavily upon speed and the long ball, usually using Jimmy Ruffell plied by the other speed merchant Victor Watson. But it was clearly inhibiting to Ruffell with the danger of tripping over spectators' legs and the general feeling of being jammed in."

According to the Stratford Express: "It was a tame finish to a disappointing match, spoiled of all its interest by the lamentable conditions under which it was decided... Bolton won because they more nearly approached their more usual form than West Ham did, and because they were less upset by the unusual happenings. On the day's play they were the better side, and deserved their victory."

The Bolton Evening News agreed: "By general consent, West Ham were conquered by a team which played with superb confidence, plainly conscious of its ability to win through... Here we had eleven men working with but a single purpose, dovetailing and blending perfectly, a mobile, virile force which operated in absolute unison and unity, whether concentrating on aggression or compelled to retreat. I cannot single out one player more than another for a special need of praise. Where all did so well, it would be invidious to individualize."

Bolton finished in 4th place in the 1923-24 season. The following season Bolton moved up to 3rd in the First Division. Bolton Wanderers had another good cup run in the 1925-26 season. The club beat Bournemouth (6-2), South Shields (2-0), Nottingham Forest (1-0) and Swansea City (3-0) to reach the final against Manchester City. Bolton won the game 1-0 with David Jack scoring the only goal of the game in the 76th minute.

Joe Smith was now 38 years old and in March 1927 he was sold to Stockport County. Smith had the great record of scoring 277 goals in 492 games. The following month, Charles Foweraker paid £2,150 for Harold Blackmore. He joined a team that included David Jack, Jimmy Seddon, John Reid Smith, Billy Butler, Ted Vizard, Dick Pym and Alex Finney.

In October, 1928, Herbert Chapman, the manager of Arsenal, decided to pay a transfer fee of over £10,890 for David Jack. He was Bolton's top scorer for five of the eight seasons he was there, scoring 144 goals in 295 league matches. Sir Charles Clegg, president of the Football Association, immediately issued a statement claiming that no player in the world was worth that amount of money. Others thought that at 29 years old, Jack was past his best. However, over the next few years Jack did everything he could to show that he was worth the money. Chapman later told Bob Wall that the buying of Jack was "one of the best bargains I ever made".

Bolton missed the goals scored by Joe Smith, David Jack and John Reid Smith and only finished in 14th place in the 1928-29 season. However, they had another good FA Cup run. They beat Liverpool (5-2), Leicester City (2-1), Blackburn Rovers (2-1) and Huddersfield Town (3-1) to reach the final against Portsmouth. Bolton won 2-0 with goals from Billy Butler and Harold Blackmore. Under the leadership of Foweraker, Bolton had won the FA Cup three times in seven years.

Bolton was less impressive in the next decade and finished 14th (1930-31), 17th (1931-32) and 21st (1932-33). After spending two seasons in the Second Division, Bolton was promoted in the 1934-35 season. Once again they struggled in the First Division finishing 13th (1935-36) and 20th (1936-37). During this period the team included Harry Goslin, Jackie Roberts, Jack Hurst, George Hunt, Harry Hubbick, Don Howe, Ray Westwood, Jack Atkinson, Tom Woodward and George Eastham.

In 1936 Harry Goslin became captain of the club. Under his leadership Bolton maintained its position in the First Division of the Football League. As the authors of Wartime Wanderers point out: "Goslin was a tall, athletic, ramrod-straight man with piercing blue eyes, whose physical presence combined with his pleasant but firm personality made him the ideal choice for club captain. Under his astute leadership the club's fortunes improved."

Charles Foweraker bought Albert Geldard from Everton for £4,500 in July 1938. Tommy Lawton was very upset by the decision to sell Geldard: "He was the fastest thing on two legs over ten yards. We had other wingers like Torry Gillick, Wally Boyes and Jimmy Caskie, but Albert had played for England only the season before, when he'd kept Stan Matthews out of the team. I thought we'd miss him."

In July 1938 Charles Foweraker was awarded the Football League's Long Service Medal in recognition of more than 21 years' service to Bolton Wanderers.

Bolton Wanderers finished in 7th place in the 1938-39 season. George Hunt ended up as top scorer with 23 goals in 37 league games. However, according to Nat Lofthouse, it was Ray Westwood who was the club's main star that season. "He was an idol of mine. A brilliant player, who knew he was a good player, but wasn't big-headed. Over ten, fifteen, twenty yards he was electric. He mesmerised me as a boy, and I wanted to be like him."

On 15th March, 1939, Adolf Hitler ordered the German Army to invade Czechoslovakia. It seemed that war was inevitable. On 8th April, Bolton Wanderers played a home game against Sunderland. Before the game started, Harry Goslin, the team captain, spoke to the crowd: "We are facing a national emergency. But this danger can be met, if everybody keeps a cool head, and knows what to do. This is something you can't leave to the other fellow, everybody has a share to do."

Of the 35 players on the staff of Bolton Wanderers, 32 joined the armed services and the other three went into the coal mines and munitions. This included Harry Hubbick, who resumed his career down the pits and Jack Atkinson and George Hunt served in the local police force. A total of 17 players, including Harry Goslin, Danny Winter, Billy Ithell, Albert Geldard, Tommy Sinclair, Don Howe, Ray Westwood, Ernie Forrest, Jackie Roberts, Jack Hurst and Stan Hanson, joined the 53rd (Bolton) Field Regiment, whereas Tom Woodward, became a Physical Training instructor.

George Caterall, Don Howe and Harry Goslin.

The government imposed a fifty mile travelling limit and the Football League divided all the clubs into seven regional areas where games could take place. Bolton Wanderers was put in the North-East League. The team included those players like Harry Hubbick, Jack Atkinson and George Hunt, who had been employed on the home front. Walter Sidebottom, a teenager who only got in the first-team at the end of the 1938-39 season emerged as a player with a very bright future. In the 1939-40 season Bolton won 13 out of their 22 games and finished in 4th place in the North-East League.

Stan Hanson, George Catterall, (Lt Col G Bennet), Billy Ithell, Jack Hurst, Front

row: Albert Geldard, Don Howe, Ray Westwood, Jackie Roberts, Tommy Sinclair.

On 12th May, 1940, Adolf Hitler ordered the invasion of France. The 53rd (Bolton) Field Regiment was sent to help the French but came under attack from the advancing Panzer divisions. Harry Goslin was credited with destroying four enemy tanks and this resulted in him being promoted to the rank of Lieutenant. Goslin, Don Howe, Ray Westwood, Ernie Forrest, Jack Hurst and Stan Hanson, were lucky to make it back to the French port of Dunkirk where they were rescued by British ships.

The 53rd (Bolton) Field Regiment spent the rest of 1940 and the whole of 1941 at various army camps around Britain. According to the authors of Wartime Wanderers: They spent their time "building coastal defence constructions, manning anti-aircraft batteries and patrolling potential enemy landing sites all along the East Anglia coastline, variously stationed at Beccles, Nancton and Holt." This enabled them to play the occasional game for Bolton Wanderers in the North-East League. The team that year included Harry Hubbick, Jack Atkinson, George Hunt, Danny Winter, Harry Goslin, Billy Ithell, Walter Sidebottom, Albert Geldard, Tommy Sinclair, Don Howe, Ray Westwood, Ernie Forrest, Jackie Roberts, Jack Hurst and Stan Hanson.

On 22nd March 1941, George Hunt, the club's leading scorer for the last two seasons, was moved to right-half and replaced at centre-forward by the 15 year-old Nat Lofthouse. Bolton won the game 5-1 with Lofthouse scoring two of the goals. Lofthouse immediately formed a good relationship with his inside-forward, Walter Sidebottom. In the first six games together they scored 10 goals between them.

Bolton Wanderers beat Blackburn Rovers 2-0 at Burnden Park on 26th April 1941. Lofthouse and Sidebottom scored the goals. It was to be Sidebottom's last game for the team as he now fell into the latest age qualification group to be conscripted into the armed forces. Sidebottom was sent to join the Royal Navy.

On 15th July 1942, the 53rd (Bolton) Field Regiment was told to mobilise for overseas service. The following month they arrived in Egypt and immediately became involved in defending Alam el Halfa. On 30th August, 1942, General Erwin Rommel attacked Alam el Halfa but was repulsed by the Eighth Army. General Bernard Montgomery responded to this attack by ordering his troops to reinforce the defensive line from the coast to the impassable Qattara Depression. Montgomery was now able to make sure that Rommel and the German Army was unable to make any further advances into Egypt.

On 22nd October 1942, the 53rd (Bolton) Field Regiment took up battle positions. The following day General Bernard Montgomery launched Operation Lightfoot with the largest artillery bombardment since the First World War. The attack came at the worst time for the Deutsches Afrika Korps as Erwin Rommel was on sick leave in Austria. His replacement, General George Stumme, died of a heart-attack the day after the 900 gun bombardment of the German lines. Stume was replaced by General Ritter von Thoma and Adolf Hitler phoned Rommel to order him to return to Egypt immediately.

The Germans defended their positions well and after two days the Eighth Army had made little progress and Bernard Montgomery ordered an end to the attack. When Erwin Rommel returned he launched a counterattack at Kidney Depression (27th October). Montgomery now returned to the offensive and the 9th Australian Division created a salient in the enemy positions.

Winston Churchill was disappointed by the Eighth Army's lack of success and accused Montgomery of fighting a "half-hearted" battle. Montgomery ignored these criticisms and instead made plans for a new offensive, Operation Supercharge.

On 1st November 1942, Montgomery launched an attack on the Deutsches Afrika Korps at Kidney Ridge. After initially resisting the attack, Rommel decided he no longer had the resources to hold his line and on the 3rd November he ordered his troops to withdraw. However, Adolf Hitler overruled his commander and the Germans were forced to stand and fight.

The next day Montgomery ordered his men forward. Lieutenant Harry Goslin and the 53rd (Bolton) Field Regiment joined the pursuit. The Eighth Army broke through the German lines and Erwin Rommel, in danger of being surrounded, was forced to retreat. Those soldiers on foot, including large numbers of Italian soldiers, were unable to move fast enough and were taken prisoner.

The British Army recaptured Tobruk on 12th November, 1942. During the El Alamein campaign half of Rommel's 100,000 man army was killed, wounded or taken prisoner. He also lost over 450 tanks and 1,000 guns. The British and Commonwealth forces suffered 13,500 casualties and 500 of their tanks were damaged. However, of these, 350 were repaired and were able to take part in future battles.

After spending time in Baghdad, the 53rd (Bolton) Field Regiment moved to Kirkurk on 8th January 1943. They were eventually relocated to Kifri which was to become their main base for the next five months. While there Harry Goslin, Stan Hanson, Don Howe and Ernie Forrest played for the British Army against the Polish Army in Baghdad. Howe scored one of the goals in the 4-2 victory.

The 53rd (Bolton) Field Regiment joined General Bernard Montgomery and the 8th Army in the invasion of Italy. On 24th September, 1943, Lieutenant Harry Goslin and his men landed at Taranto. Three days later the men had reached Foggia without too much opposition. However, when the men were ordered to cross the River Sangro the regiment took part in some of the most difficult fighting of the Second World War.

At the end of November Don Howe was wounded and evacuated to a dressing station. After another enemy air attack Ray Westwood and Stan Hanson came close to being killed. The shelling continued and on 14th December, 1943, Harry Goslin was hit in the back by shrapnel. He died from his wounds a few days later. The Bolton Evening News reported: "Harry Goslin was one of the finest types professional football breeds. Not only in the personal sense, but for the club's sake, and the game's sake. I regret his life has had to be sacrificed in the cause of war."

What was left of the 53rd (Bolton) Field Regiment moved to Monte Cairo, five miles north-west of Monte Cassino, on the main road from Naples to Rome. The Allied Commander-in-Chief, General Harold Alexander, told his men: "Throughout the past winter you have fought hard and valiantly... tomorrow we can see victory ahead. We are going to destroy the German armies inItaly." On 11th May 1944 the great British artillery programme bagan. Ernie Forrest and Jack Hurst, like many of the men serving in the artillery, began to suffer hearing loss because of the noise of this bombardment.

Jackie Roberts was caught in the blast of an enemy shell and had taken heavy shrapnel in the face, detaching the retina, and was immediately invalidated out of Italy and returned to Bolton. However, most of the Bolton players in the 53rd Field Regiment continued in the advance on Rome.

Bolton Wanderers lost their second first-team player when Walter Sidebottom was drowned when his ship was torpedoed in the English Channel in November 1943.

The young Nat Lofthouse continued to score on a regular basis but in 1943 he became a Bevin Boy and worked as a miner in a local colliery. As Dean Hayes points out in his book, Bolton Wanderers (1999): "Bevin Boy Lofthouse's Saturdays went like this: up at 3.30 a.m., catching the 4.30 tram to work; eight hours down the pit pushing tubs; collected by the team coach; playing for Bolton. But work down the mine toughened him physically and the caustic humour of his fellow miners made sure he never became arrogant about his success on the field."

Walter Rowley became manager on the retirement of Charles Foweraker in August 1944. Rowley was able to make use of players who had returned to England after military victories in North Africa and Italy. The team that season included Harry Hubbick, Nat Lofthouse, George Hunt, Lol Hamlett, Jack Hurst, Tommy Sinclair, Willie Moir, Malcolm Barras, Albert Geldard, Jack Atkinson, Stan Hanson, Ray Westwood, Tom Woodward, Jackie Roberts, Don Howe and Ernie Forrest.

In the first round of the Football League War Cup (North) Bolton beat Accrington Stanley 4-1 with Nat Lofthouse scoring two of the goals. Lofthouse went on to score a hat-trick against Blackpool. This was followed by victories over Newcastle United and Wolverhampton Wanderers to reach the final against Manchester United.

The final was played over two legs. In the first game Nat Lofthouse scored in a 1-0 victory at Bolton. The return game finished 2-2 with both Bolton goals being scored by Malcolm Barras. Therefore Bolton won the final 3-2.

On 2nd June 1945, Bolton played the winners of the Football League War Cup (South). Chelsea took an early lead but George Hunt scored an equalizer early in the second-half. Just before the end of the game Malcolm Barras was brought down in the penalty area. As Lol Hamlett walked up to take the penalty, a number of upset Chelsea fans invaded the pitch and after a short scuffle grabbed the ball and for a while they refused to give it back. After the ball was retrieved and the fans cleared from the pitch, Hamlett scored the winning goal.

Bolton finished in 3rd place in the North League 1945-46 season. The leading scorers were Nat Lofthouse (21), Willie Moir (9), Malcolm Barras (7) and George Hunt (6).

On 9th March 1946 Bolton Wanderers played Stoke City in a FA Cup tie. Over 80,000 people entered the Burnden Park ground before the club closed the gates. Some locked out fans decided to climb over the walls in order to see the game. Hundreds of spectators were pushed down a barrier-less section of the embankment under the weight of the crowd. A police officer walked onto the pitch towards the referee. He blew his whistle to stop the game and Nat Lofthouse saw the officer point towards the bodies lying motionless at the edge of the pitch saying: "I believe those people over there are dead." Thirty-three people died and over 400 were injured in the disaster.

In 1946 Bolton Wanderers reached the semi-final of the FA Cup but were beaten 2-0 by Charlton Athletic. Bolton finished 18th in the First Division in the 1946-47 season. This was followed by 17th (1947-48), 14th (1948-49) and 16th (1949-50). In October, 1950, Walter Rowley resigned as a result of ill-health.

Stanley Matthews wrote in his autobiography that: "At half-time we sipped our tea and listened to Joe. He wasn't panicking. He didn't rant and rave and he didn't berate anyone. He simply told us to keep playing our normal game." Harry Johnson, the captain, told the defence to "be more compact and tighter as a unit." He also added: "Eddie (Shinwell), Tommy (Garrett), Cyril (Robinson) and me, we will deal with the rough and tumble and win the ball. You lot who can play, do your bit."

Despite the team-talk Bolton Wanderers took a 3-1 lead early in the second-half. Robinson commented: "It looked hopeless then, I was thinking to myself at least I've been to Wembley." Then Stan Mortensen scored from a Stanley Matthews cross. According to Matthews: "although under pressure from two Bolton defenders who contrived to whack him from either side as he slid in, his determination was total and he managed to toe poke the ball off the inside of the post and into the net."

In the 88th minute a Bolton defender conceded a free kick some 20 yards from goal. Stan Mortensen took the kick and according to Robinson: "I've never seen one taken as well. It flew, you couldn't see the ball on the way to the net." Matthews added that "such was the power and accuracy behind Morty's effort, Hanson in the Bolton goal hardly moved a muscle."

The score was now 3-3 and the game was expected to go into extra-time. In his autobiography, Stanley Matthews described what happened next: "A minute of injury time remained... Ernie Taylor, who had not stopped running throughout the match, picked up a long throw from George Farm, rounded Langton and, as he had done like clockwork through the second half, found me wide on the right. I took off for what I knew would be one final run to the byline. Three Bolton players closed in, I jinked past Ralph Banks and out of the corner of my eye noticed Barrass coming in quick for the kill. They had forced me to the line and it was pure instinct that I pulled the ball back to where experience told me Morty would be. In making the cross I slipped on the greasy turf and, as I fell, my heart and hopes fell also. I looked across and saw that Morty, far from being where I expected him to be, had peeled away to the far post. We could read each other like books. For five years we'd had this understanding. He knew exactly where I d put the ball. Now, in this game of all games, he wasn't there. This was our last chance, what on earth was he doing? Racing up from deep into the space was Bill Perry."

Stanley Matthews added that Perry "coolly and calmly stroked the ball wide of Hanson and Johnny Ball on the goalline and into the corner of the net." Bill Perry admitted: "I had to hook it a bit. Morty said he left it to me, but that's not true, it was out of his reach." Blackpool had beaten Bolton Wanderers 4-3. Matthews, now aged 38, had won his first cup-winners medal.

Bolton Wanderers continued to struggle in the First Division but Nat Lofthouse remained in good form and was the club's top scorer in 1954-55 (15), 1955-56 (32), 1956-57 (28) and 1957-58 (17). Bolton also enjoyed a good FA Cup run that season beating York City (3-0), Stoke City (3-1), Wolverhampton Wanderers (2-1), Blackburn Rovers (2-1) to reach the final against Manchester United. Lofthouse scored both goals in the 2-0 victory.

Primary Sources

(1) Bolton Evening News (30th April, 1923)

It had been confidently stated that this new amphitheatre, the home of English sport, was structurally and scientifically perfect, offering comfortable accommodation and an unobstructed view to upwards of 125,000 spectators. Clearly the authorities were totally unprepared for what happened. It is computed that fully 250,000 people made their way to the imposing and spacious ground form all parts of the Empire, all anxious to see the blue riband of the football world decided. About 60,000 people had passed inside the turnstiles when pandemonium broke loose.

One of the main exits was broken down and thousands of people surged inside the enclosure, and from that moment the situation showed signs of getting out of hand. People scaled high walls and clambered into seats for which others had paid. Such was the pressure on the ringside fences that they gave way. The crowd rushed across the large cinder track which encircles the playing pitch, and in an incredibly short time the beautiful greensward was occupied by a black uncontrollable mass. The police, apparently taken by surprise, were for a time powerless to deal with the situation and even after more officers, mounted and on foot, had been rushed to the ground, the task of clearing the playing pitch was a tediously slow process. Indeed, when the players came into the arena, there seemed very little prospect of the game being started. finally, however, when the players added their persuasion to the force resorted to by the constabulary, the crowd was gradually pressed back to the touchline, and at 14 minutes to four the referee found it possible to make a start.

The Bolton party made the Russell Hotel their headquarters for the weekend, the players with the manager, Mr E.B. Foweraker, having spent the last few hours before the match at Harrow, and they made the short journey to the ground in excellent time. But the directors and their friends, who journeyed from London in charabancs, had an experience they will never forget. They certainly have no desire to see Wembley again. The road was packed with vehicular traffic for long stretches trams, buses, charabanc, motors and horse conveyances were running four abreast, and frequently were held up for long periods at cross roads. The journey occupied two hours - and when the party had to alight, fully half a mile from the vast amphitheatre, many of us had abandoned hope of seeing any play in the first half. With scores of others, I made my way across a grass field, crossed a railway, scaled a high wall, and then found my way into the enclosure obstructed by corrugated iron hoardings with three rows of barbed wire above them. Some of the more daring spirits surmounted this formidable obstacle, whilst others less venturesome burrowed under the hoardings only to find more difficulties ahead. Nobody seemed to know how to get inside the enclosure, and there were thousands of people shut out. It was my good fortune to reach the Press seats at the top of the north stand at 3-40, and then greatly to my relief I learned that the match had not started.

Dozens of Bolton people saw none of the game. None of the directors saw the first goal, and several of them did not get as much as a glimpse of the game. Scores of people who had paid a guinea for a seat never got it. Never in the history of the game has there been such a tragedy, and for the credit of those who are responsible for the good government of Soccer, the most popular of all pastimes, it is to be hoped it will never be repeated. The Football Association have since disclaimed any responsibility for what happened. They point out that all the arrangements were in the hands of the Wembley authorities. I venture to suggest the FA are merely begging the question by taking such an attitude. The public look up to the FA, and indeed to every football body, to keep faith with them, and such a debacle as this will do unquestionable harm to the game. The invasion of the playing field was due, it is alleged, to the snapping of the barriers when the in rush of spectators followed the breaking-in of the gates.

(2) The Times (30th April, 1923)

The Bolton Wanderers beat West Ham United in the Cup Final at the Wembley Stadium on Saturday by 2 goals to 0.

This bald statement represents the result of the football side of a matter which has been discussed from many points of view for months. The fact that the Wembley Stadium has been advertised as the greatest of its kind had much to do with the enormous crowd which came from all sorts and conditions of places to see the first Cup Final to be played there. The claims made for the Stadium were not in the slightest degree extravagant. It was built to hold 125,000 people in comfort and to give to each and every one of that huge total a fair view of the football ground and track. The Stadium can hold even more than that number, and yet give to all the spectators a fair view, but no building and ground could accommodate 300,000 people, and at least that number must have turned up on Saturday at Wembley.

The reasons for the mammoth congregation were many. The opening of the Stadium for the first Cup Final might become - as in fact it has become - an historic occasion. There was the fact that a London club were in the Final Tie; the day was perfect; and, by the irony of fate, the superb organisation of the many railway lines converging on the stations round the Stadium was the crowning factor in producing such a crowd that it was impossible for any arrangements there to be carried out according to plan.

Except on two important points - the spirit of the people and of the police, and the absolute loyalty, of a very mixed congregation, to the King - the day was an ugly one. Many ticket-holders never reached their seats; others got to their seats in plenty of time and were pushed out of them; whirled away like straws on a stream by the sheer weight of numbers sweeping irresistibly forward from behind. The crowd was out of hand, very often most unwillingly. By 2.30 p.m. many people were attempting to get back the way they had come, the one more difficult thing than pushing on as indeterminate atoms of the throng. The playing-ground on Saturday morning was a beautiful picture. Later on, there must have been tens of thousands of people on it at one time. It was defiled with orange peel and papers and refuse, but the surface stood the trampling of the mob, the police, and the hoofs of the horses of the mounted police most astonishingly well. Many of the thousands on the field of play were not there of their own volition - they were whirled away from seats and places of vantage secured by patient waiting. By the help of large reinforcements of police, mounted and unmounted, and the players, who appealed right and left for fair play, the ground was gradually cleared, the people being pushed back to the touch-lines. That play could ever be begun and continued seemed, at one time, quite impossible. That the seemingly impossible could and did happen was, one must believe, owing to the presence of the King, whose reception when he reached the ground was an event to remember. It was after "God Save the King" had been sung with boundless enthusiasm that the people began, slowly enough, it is true, to help rather than to hinder in the clearing of the ground.

At 3.45 it was possible to kick off. Some eleven minutes later, a part of the crowd were squeezed on to the ground, but play was again possible after ten minutes' patient work on the part of the police. The Bolton Wanderers were leading at the time by one goal to none, having scored in the first two minutes; but, five minutes before the second interruption, West Ham United had nearly equalised, Watson missing a chance which he would have taken with absolute certainty on an ordinary occasion.

Taken merely as an Association Football match, the play at Wembley on Saturday was rather disappointing. No doubt, the long wait and the doubt as to the possibility of the game being finished, even if begun, had an effect on players already keyed up to a high state of tension. To win a Cup-tie medal is preferred, by quite a many, to winning an international cap. West Ham United had not only been preparing to win the Cup, they had also, if possible, to force their way into the League Championship next season. The double event has proved beyond their powers, but they certainly deserve promotion on the season's play. They were a good side for the first ten minutes of the great final, but, afterwards, they were never convincing. When the sun was against them in the first half both the backs and the half-backs kicked too high and too hard. In the second half, when the sun was shining in the faces of the Bolton Wanderers' defence, the high kicking, followed by a rush, with all the forwards in something like a line, might have proved extremely good tactics. The Bolton Wanderers' backs and half-backs, however, seldom had to use their heads for safety in the second half. The game was started at a great pace, and the Bolton Wanderers scored after just two minutes play. Nuttall dribbled up the field, half drew a man, and passed perfectly to Jack. Jack took the ball along slowly and feinted to pass out to Butler; when the pass looked as good as made, he dribbled inside to the left, went through the West Ham United defence at a great pace and scored from close in with a hard high shot into the right-hand corner of the net. Hufton could strike only at the direction in which he hoped the ball would take, and he cannot be blamed for letting the ball pass him. Three minutes later came the great chance for West Ham United to equalise. Pym, misjudging a perfectly taken corner by Ruffell, came out of goal and missed the ball. The ball came to Watson, who had an open goal yawning only a few yards in front of him. How he managed to kick the ball over the cross-bar instead of into the net one cannot imagine; if a player tried to do it, the odds against him would be generous. Watson, however, did fail to score.

West Ham United were every bit as good as their opponents until the second stoppage of play occurred. Even when the match was continued the crowd were actually on the touch-line and sometimes over it. The West Ham United outsides never showed confidence near to the crowd ; one was reminded constantly of the speech of the Maltese Cat on the subject of crowding in Rudyard Kipling's wonderful polo story, called after the great pony. Now Vizard seemed to enjoy the human wall which marked or obliterated the touch-line. On an ordinary day Bishop might have held him; in the circumstances his mentality was at fault, for which he is scarcely to blame. Richards made one brilliant dribble and break through for West Ham United and Pym fumbled a clever shot, though he eventually cleared comfortably. A little later a beautiful centre by Vizard was headed just wide by J. R. Smith. Bolton Wanderers continued to attack, and J. R. Smith scored from a clever centre from Butler. J. R. Smith was ruled offside, although he appeared to be well behind the ball when it was kicked. The Press Stand, however, is some distance in mere yards from the field of play, and the angle was not easy to judge. Until half-time Bolton Wanderers were always the more dangerous combination, and, but for the magnificent game which Henderson played at right full-back, they would probably have scored again on at least one occasion.

The teams did not leave the field at half-time - if they had done so, the match would not have been finished on Saturday - but crossed over and resumed play after a five-rninutes' interval. West Ham United began the second half well, and Watson had a good chance from a centre of Kay's, the centre-half having worked out on to the wing with a clever individual effort. Watson, however, misjudged the flight and direction of the ball and did not start for it in time. Pym saved two shots quietly and confidently and then came the movement that settled the result of the match. Vizard niggled the ball down the wing, very close to the touchline. Suddenly he kicked and ran, passed Bishop and centred right across the goal mouth. J. R. Smith got to the ball and shot immediately. The ball hit the inside of the cross-bar and bounced out again into play. It was, however, a goal and the referee had not the slightest hesitation in ruling it as such. Even before this goal was scored a rivulet of spectators were leaving the ground; now this rivulet swelled to a steady stream. The match, to all intents and purposes, was over.

Bolton Wanderers, on the day's play, were always the better side after the first ten minutes. They did not realise the hopes of the big contingent of their supporters, whose Saga, after the second goal was scored, "One, Two, Three, Four, Five", was repeated mechanically and at brief intervals until the finish. Seddon, the Bolton Wanderers centre-half-back, carried off the honours of the match. He called the tune to his side, and generously they piped. All of them could be picked out for good work, at times for brilliant work; but the other ten would be the first ten to award merit where merit was due, and would fasten on Seddon as the ultimate winner of the F.A. Cup.

At the finish of the match the King presented the Cup to J. Smith, the captain of the Bolton Wanderers, and the medals to the different players. He drove away amidst a scene of heartfelt enthusiasm.

(3) Bolton Evening News (30th April, 1923)

Comments on the collective and individual merits of the players must be brief. By general consent, West Ham were conquered by a team which played with superb confidence, plainly conscious of its ability to win through. The Wanderers went about their work right from the outset in a manner which seemed to suggest "We are bound to beat the best team in the Second Division if only we play our natural game." It was what is known as one of the most valuable asserts any combination of footballers can develop - team spirit - that pulled the "Trotters" though. Here we had eleven men working with but a single purpose, dovetailing and blending perfectly, a mobile, virile force which operated in absolute unison and unity, whether concentrating on aggression or compelled to retreat. I cannot single out one player more than another for a special need of praise. Where all did so well, it would be invidious to individualize. Suffice it to say that in a comparatively quiet afternoon, Pym made one thrilling save, and displayed fine judgement and anticipation; that the two young backs, Haworth and Finney, never faltered; that Seddon, a giant in every phase of the game, had two polished wing halves as colleagues, and that the whole forward line worked together untiringly and with no little skill to lead and lure the "Hammers" rear-guard into false positions. There was nothing of the "hammer-your-way-though" policy about the Bolton attacks.

(4) The Stratford Express (2nd May, 1923)

There was every prospect, under normal conditions, of witnessing one of the finest exhibitions ever seen in a final for the Cup, but in the circumstances neither side showed its best form. Bolton won because they more nearly approached their more usual form than West Ham did, and because they were less upset by the unusual happenings. On the day's play they were the better side, and deserved their victory. They were better together as a team, and displayed more understanding. Their passes did not go astray so much as those by the West Ham players, on whose part generally there was a singular lack of enterprise. It was fairly obvious that they were upset by the day's happenings, and the two wingers, Richards and Ruffell, only occasionally showed flashes of speed. They did not at all relish playing on top of the spectators. On the other hand, Vizard, the clever Bolton left winger, seemed not in the least perturbed, and it was from him and J.Smith that most of the trouble came for the West Ham defence. Bishop and Henderson stuck to their task against these two with great perseverance, without always being able to stop their progress. Generally, however, the defence did well, although two goals were scored against it. The real reason of the side's downfall was because of the weakness in finishing and lack of enterprise on the part of the inside forwards. The wing men were cramped for room mostly, but Watson was nearly always dominated by Seddon, the Bolton centre-half, and Moore and Brown, the inside wingers, failed to take advantage of the constant shadowing of the centre-forward. The Bolton backs were tireless tacklers and clean in their kicking and performed in combination with the half backs.

(5) Syd King, statement (5th May, 1923)

Although inundated with requests to lodge a protest against the result of the final tie, the directors of the West Ham club are satisfied that they were beaten by the better team on the day (under the conditions in which the match was played) but they do consider that the responsible officials of both clubs should have been informed at half-time as to whether the match was to be a Cup-tie or not; as in their opinion the match was not played under the rules of the FA (particularly with regard to Rule 5). Rule 5, deals with the conditions under which the ball shall be thrown from the touchline, but on Saturday the crowd were on the touchline practically all the time.