Transfer System

In 1893 Jack Southworth was transferred from Blackburn Rovers to Everton for £400. It has been claimed that this was the first-time that money had changed hands between football clubs for a professional player. Blackburn was very upset at losing their star centre-forward who had helped them win the FA Cup finals in 1890 and 1891. Southworth went on to score an amazing 36 goals in 31 games for his new club in the 1893-94 season.

Good goalkeepers were also in demand. One of the best was Jack Hillman of Burnley. As Mike Jackman pointed out in The Legends of Burnley, Hillman was "one of the great exponents of goalkeeping during the Victorian period." In February 1895, Hillman was transferred to Everton for £200. He only missed one game that season and helped his new club to finish in 3rd place in the First Division of the Football League.

The Football Association was determined to keep professional players under its control. In 1893 a regulation was introduced that compelled all professional players to register annually with the FA. No player was allowed to play until he was registered, nor was he free to change clubs during the same season without the FA's permission.

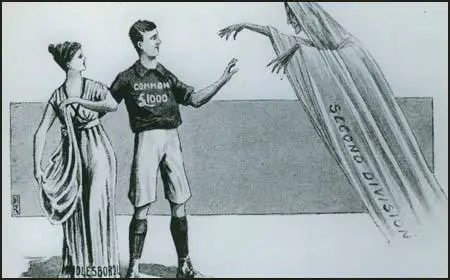

The Football League then introduced a new rule that stated that any professional player who wished to move on to another club had to obtain the permission of his present club. The Football League also insisted that once signed, a player was tied to his team for as long as the club wanted him. Therefore, if a player refused to sign a new contract at the beginning of the season, he could not sign for no one else unless the club gave permission.

This measures introduced created the transfer system that still exists today. However, in 1893, the players were not free to negotiate a new contract on anything like equal terms with their employers. The Football League had in fact abolished the free market and clubs could now reduce player wages without losing their services.

In September, 1893, Derby County proposed that the Football League should impose a maximum wage of £4 a week. At the time, most players were only part-time professionals and still had other jobs. These players did not receive as much as £4 a week and therefore the matter did not greatly concern them. However, a minority of players, were so good they were able to obtain as much as £10 a week. This proposal posed a serious threat to their income.

In February 1898, a group of players on high wages announced the formation of Association Footballers' Union (AFU). John Bell became chairman of the union. The secretary of the AFU, John Cameron, announced that the union had 250 members. Cameron pointed out that their main objective was that they "wanted any negotiations regarding transfers to be between the interested club and the player concerned - not between club and club with the player excluded".

In 1893 J.J. Bentley became president of the Football League. Bentley opposed the power of the Football Association and objected to the decision that stated that no transfer fee of more than £10 be paid by football clubs. As Bentley pointed out in 1899: "The serious battle will be fought on what the League considers a principle and that is being allowed to work its own particular competition in its own particular way whilst at the same time observing the rules of the parent body."

The AFU was badly wounded by the decision of several members of the committee to seek higher wages in the Southern League. This included the AFU secretary John Cameron, who joined Tottenham Hotspur for the 1898-99 season. Tom Bradshaw also joined Spurs, whereas other leading figures in the union who left the Football League included Harry Wood and Abe Hartley (Southampton), Johnny Holt (Reading) and Jack Bell and David Storrier who joined Celtic.

Clubs in the Football League was forced to pay high transfer fees to get the best players. In the 1900-01 season Sunderland finished 2nd to Liverpool in the First Division championship. The team included Alf Common who was considered the best young goalscorer in England. At the end of the season, Sheffield United paid Sunderland £350 for Common. He repaid the investment by scoring the only goal in Sheffield's 1902 FA Cup Final win. Common continued to do well for Sheffield United and in the summer of 1904, Sunderland bought him back for a new record fee of £520.

Manchester United became a force in the transfer market when rich businessman, John Henry Davies, became chairman of the club. Ernest Mangnall became the new manager and in 1904 he paid Grimsby Town £600 for 21-year-old Charlie Roberts. At the time Mangnall was criticised for paying such a large sum for such an inexperienced player. However, it proved to be an inspired decision and it was not long before Roberts established himself as the keystone of the Manchester United defence.

John Henry Davies arranged for J.J. Bentley, the president of the Football League and the vice president of the Football Association to be appointed as president of Manchester United. Bentley now joined forces with the Association Football Players Union (AFPU) to get the maximum wage removed.

In February, 1905, Middlesbrough, who were in danger of being relegated from the First Division. Thomas Gibson Poole, the chairman of the club, purchased Alf Common from Sunderland for a record breaking fee of £1,000. One journalist described the transfer of Common as "flesh and blood for sale". Another sports writer wrote: "We are tempted to wonder whether Association football players will eventually rival thoroughbred yearling racehorses in the market."

Once again the transfer of Alf Common had the desired impact on the fortunes of the club. On 25th February, Common scored the only goal of the game against Sheffield United. It was Middlesbrough's first away victory for over two years. Common helped to save Middlesbrough from relegation and over the next five years he scored 58 goals in 168 games.

In January 1908, the Football League imposed a £350 limit on the cost of players. This proved ineffective as clubs got round the regulation by doing deals involving the selling of several players together. For example, in order to get £1,000 for their star player, they included two other poorly rated players in the deal. Officially, each one was sold for £350. After a year the league withdrew the regulation.

Harold Halse was one of those players who was purchased for £350 in 1908. He had scored 91 goals in 64 games for Southend United before joining Manchester United. In two seasons Halse helped United win both the Football League title and the FA Cup.

in March 1911, Sunderland paid a record transfer fee of £1,200 for Charlie Buchan. He later complained he only received a £10 signing on fee for the move. Another player who was sold for £1,200 during this period was Robert Young who went from Middlesbrough to Everton. This was a amazing fee considering that Young was a defender and had never played for his country.

Lawrence Cotton, a local wealthy businessman, was chairman of Blackburn Rovers. He was determined to create a team capable of winning the First Division title. Blackburn's manager, Robert Middleton signed several international players such as Billy Davies and Jimmy Ashcroft. In 1911 Middleton purchased Jock Simpson from Falkirk for a fee of £1,800. That season Blackburn won the title by three points from their main challengers, Everton. It was the first time in Blackburn's history that they had won the league title.

Blackburn started the 1912-13 season very well and were undefeated until December. This was followed by five successive defeats. In an attempt to regain the championship, Robert Middleton broke the British transfer record by buying Danny Shea from West Ham United for £2,000. Patsy Gallagher, described Shea as "one of the greatest ball artists who has ever played for England... his manipulation of the ball was bewildering."

Robert Middleton also purchased another forward, Joe Hodkinson for £1,000. Shea scored 12 goals but it was not enough and Blackburn finished 5th that season.

In the 1913-14 season Blackburn once again won the league title. Danny Shea was in great form scoring 27 goals. Other expensive transfers buys such as Jock Simpson and Joe Hodkinson also made substantial contributions to the success of the club and that year won places in the England team.

Charlie Roberts had been the captain of the Manchester United team that won the First Division championship in 1907-1908 and 1910-1911. Although he was aged 30 years old, Oldham Athletic paid a fee of £1,750 for Roberts in 1913. Roberts brought success to Oldham and in the 1914-15 he captained the club to the highest position in the club's history, runners-up to Everton in the First Division championship.

In the 1914-15 season Lawrence Cotton provided the money to enable Blackburn Rovers break the transfer record again when they bought Percy Dawson for £2,500 from Heart of Midlothian. Blackburn scored 83 goals in 1914-15 season. However, their defence was not as good and Blackburn finished 3rd behind the champions, Everton. Dawson was top scorer with 20 goals.

Blackburn Rovers had shown that it was possible to buy success. The top clubs were especially willing to pay top prices for goalscorers. Horace Barnes scored 74 goals in 153 league games for Derby County. In 1914 Manchester City paid a record transfer fee of £2,500 for Barnes. During his first season at Maine Road he scored 22 goals in 39 games. However, the First World War interrupted his football career and like Danny Shea, he was past his best when the Football League resumed in 1919.

In October 1919, Frank Barson became Britain's most expensive player when Aston Villa paid Barnsley £2,850 for his services. Barson was a great success at his new club. In their book, The Essential Aston Villa, Adam Ward and Jeremy Griffin argue that: "When Frank Barson arrived at Villa Park in the winter of 1919 he provided much-needed backbone to a team that was floundering hopelessly at the foot of Division One. Barson was a 1920s Stuart Pearce - feared for his biting tackles and competitive spirit, but admired for his ability on the ball."

The chairman of the football clubs began to complain that players were engineering transfers in order the obtain large signing-on fees. For example, Danny Shea received £550 for signing for Blackburn Rovers just before the First World War. In an attempt to reduce transfer activity the Football League altered the rules in 1920 so that players were no longer permitted to receive a share of their fee.

In 1920 Bolton Wanderers paid Plymouth Argyle £3,500 for David Jack. Although only 21 he looked a great prospect for the future. In his first season he helped Bolton finish 3rd in the First Division of the Football League. Two years later Bolton reached the first FA Cup Final held at Wembley Stadium. Jack scored the opening goal in Bolton's 2-0 victory over West Ham United. Jack went on to score 144 goals in 295 games for Bolton.

Harry Bedford was another player who scored a great deal of goals during this period. He signed for Blackpool in 1920. Bedford was the country's top goalscorer in the 1922-23 with 32 goals. He repeated the feat the following season with 34 goals. After scoring 112 goals in 169 games for Blackpool, Bedford was transferred to Derby County for £3,000 in 1925. During his time at the club he scored 142 goals in 203 games.

Another exciting young talent who emerged at this time was Syd Puddefoot. He was playing junior football in the East End of London when he was spotted by Syd King, the manager of West Ham United. Like Danny Shea he was a scoring machine and netted 107 goals in 194 games for the club. In February 1922 Falkirk became the first club to pay £5,000 for a player when they signed Puddefoot. He was very reluctant to move to Scotland and later complained that his teammates refused to pass to him in games. Whatever, the reasons, unlike previous big money buys, Puddefoot failed to provide success for his new club and the Scottish League remained dominated by Celtic and Rangers.

Hughie Gallacher was a highly successful centre-forward with Airdrieonians in the Scottish League. During a four year period he scored 91 goals in 111 games. In 1925 Newcastle United paid Airdrieonians £6,500 for Gallacher. He made an immediate impact and during his first season scored 23 goals in 19 games. The following season Newcastle won the First Division league title. Gallacher, who had been made captain of the side, scored 39 goals in 41 games. After scoring 133 goals in 160 league appearances, Gallacher was sold to Chelsea for £10,000.

In May 1925 Herbert Chapman visited Charlie Buchan in his sports outfitters shop. He asked him if he was willing to be transferred to Arsenal. Buchan, who had scored 209 goals in 380 games for Sunderland, agreed and after two months of negotiations, he joined the London club. Bob Kyle, the Sunderland manager, explained to Buchan the complex arrangements of the deal: "We pay Sunderland cash down £2,000, and then we hand over £100 to them for every goal you score during your first season with Arsenal." Buchan scored 21 goals that season which brought the amount paid by Arsenal to Sunderland to £4,100.

In March 1925 Dixie Dean was transferred from Tranmere Rovers to Everton for a fee of £3,000. Dean was one of the best signings of all times. Dean was in sensational form in the 1927-28 season. He scored seven hat-tricks that season and ended up with a record-breaking 60 league goals. Dean helped Everton win three league championships and a FA Cup final victory. During his time at Everton he scored 349 goals in 399 games.

In 1925 Frank Richards, the manager of Preston North End, a Second Division club, paid £3,000 for Alex James, a free-scoring inside-forward from Raith Rovers in the Scottish League. James did well in his first season ending up as the club's top scorer with 14 league goals. He also won his first international cap when he played in Scotland's 3-0 victory over Wales in October, 1925. Alex James developed a good partnership with centre-forward, Tommy Roberts, who scoring 30 goals in the 1926-27 season. James not only scored a lot of goals, he was also a provider of chances for others.

James attracted the notice of all the top clubs when he scored two spectacular goals in Scotland's 5-1 victory over England at Wembley on 31st March, 1928. In four years at Preston North End Alex James had scored 55 goals in 157 appearance. He also supplied the passes that resulted in plenty of goals for his strike partners, Tommy Roberts, Norman Robson and Alex Hair.

James had become frustrated with playing Second Division football. He was also upset with Preston for not always releasing him to play international games for Scotland. Most of all, he was dissatisfied with his wages. At the time, the Football League operated a maximum wage of £8 a week. However, other clubs had found ways around this problem. This included Arsenal who signed James for £8,750 in 1929. Herbert Chapman, the manager of Arsenal, arranged for James to obtain a £250-a-year "sports demonstrator" job at Selfridges. It was also agreed that James would be paid for a weekly "ghosted" article for a London evening newspaper.

In October, 1928, Herbert Chapman, the manager of Arsenal, decided to pay a transfer fee of £10,890 for David Jack of Bolton Wanderers. Sir Charles Clegg, president of the Football Association, immediately issued a statement claiming that no player in the world was worth that amount of money. Others thought that at 29 years old, Jack was past his best. However, over the next few years Jack did everything he could to show that he was worth the money. Chapman later told Bob Wall that the buying of Jack was "one of the best bargains I ever made".

The buying of Alex James and David Jack helped to make Arsenal the dominant club in the country. Their first success was winning the 1930 FA Cup Final. In the 1930-31 season Arsenal won their first ever First Division Championship. The following season they lost the title by two points to Everton. Arsenal regained the championship in 1932-33. They also scored a club record of 118 goals in the league that season. Arsenal made it four out of five when they won the league the following season, beating Huddersfield Town into second place.

In 1936 Peter Doherty was transferred to Manchester City for a club record fee of £10,000. Doherty wanted to remain with Blackpool. As he later pointed out: "My personal feelings counted for next to nothing in the transaction. I might as well have been a bale of merchandise." The following season City won the First Division championship with Doherty scoring 30 of the goals.

In December, 1936, Everton signed Tommy Lawton from Burnley for a fee of £6,500. The remarkable feature of this transfer was that Lawton had just celebrated his 17th birthday and that it was a record fee for a teenager. He was a great success at the club and went on to score 70 goals in 95 games.

Alex James retired in 1937 and Arsenal manager, George Allison, began looking for a replacement. In 1938 he purchased Bryn Jones from Wolverhampton Wanderers for a world record fee of £14,000 (£6.9 million in today's money). Politicians were outraged by the money spent on Jones and the subject was debated in the House of Commons.

Bryn Jones scored on his debut against Portsmouth. He also found the net in two of his next games. However, the goals dried up and he was only to get one more before the end of the season. After Arsenal were beaten at home 2-1 by Derby County, the match reporter from the Derby Evening Telegraph wrote: "Arsenal have a big problem. Spending £14,000 on Bryn Jones has not brought the needed thrust into the attack. The little Welsh inside-left is clearly suffering from too much publicity, and is obviously worried. He is a nippy and quite useful inside-left, but his limitations are marked.

"In his first season Bryn Jones scored four goals in 30 league appearances. That year Arsenal finished 5th in the league, eight points behind Wolverhampton Wanderers who appeared to be doing very well without Jones. As Jeff Harris pointed out in Arsenal Who's Who (1995): "To lay blame on Bryn Jones for the club's lack of success that season was unfair, for in a nutshell, the quiet, modest, self evasive, lonely figure could not cope with the intense pressure of the media spotlight even though his good positional awareness and splendid ball control were there for everyone to behold." His manager, George Allison, claimed that Jones needed more time to settle into the team. However, the outbreak of the Second World War brought an end to this discussion. Bryn Jones joined the British Army and served with the Royal Artillery in Italy and North Africa during the conflict.

In November 1947, Tommy Lawton was transferred to Notts County, a club playing in the Third Division at the time, for the record fee of £20,000. Lawton scored 90 goals in 151 games for the club, but it was not until the 1949-50 season that Notts County won promotion to the Second Division.

Primary Sources

(1) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

Throughout the week-end, they visited the Leyton ground and my home at Woolwich. I told them all to interview my father who put some of them off with the news that I would not leave home. The size of the transfer fee asked by Leyton put others off.

Then, on the Tuesday, I went to the Leyton ground. Manager Dave Buchanan told me I was wanted in the office. Bob Kyle, Sunderland manager, was waiting there.

When I went in, he said: "How would you like to play for Sunderland in the First Division? You'll get maximum wages and a ten pounds signing-on fee."

To be perfectly frank I did not know exactly where Sunderland was. I knew it was on the north-east coast somewhere near Newcastle, but that was all. It seemed very far away from home.

After talking the matter over, Kyle said: "You know, you'll never get a better chance. I can promise you a place in the first team for the rest of this season at least."

That settled the argument. I signed, received the £10 fee, and went in the dressing-room to prepare for training. When Dave Buchanan heard I had signed he was the most disappointed man I met. He wanted me to go to Everton.

The Sunderland manager came into the dressing-room a minute or two afterwards and said: "Son, it's very cold up north, so I advise you to get an outfit of thick winter clothes. You'll need them."

I did. I bought a new, lined overcoat (£4 4s) a tweed suit (£2 10s), in fact, a completely new outfit of what I thought would keep me warm in any climate. And the whole lot did not amount to the £10 signing fee. Today they would cost nearer £100. But within six months, they were no use to me whatever. I had grown right out of them.

(2) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

Bob Kyle went into the transfer market. He bought Charlie Gladwin, six-foot-one-inch, fourteen stone Blackpool right-back, and Joe Butler, Stockport County goalkeeper.

Local people thought he must have gone crazy to pay something like £3,000 for the two. In those days, when the record transfer fee was £1,850, paid by Blackburn Rovers to West Ham United for inside-right Danny Shea, it was a lot of money, worth, I should say, ten times the amount today.

It was money well spent. From the moment Gladwin and Butler joined the side, Sunderland went ahead and became the finest team I ever played for, and one of the best I have ever seen.

Not only did we win the League Championship with a record number of points, but we nearly brought off the elusive League and Cup double, accomplished only by Preston North End and Aston Villa...

There are people who say that no one player can make a poor side into a great one, and that there isn't one worth £3,000 transfer fee. Gladwin proved they are wrong.

(3) Tommy Lawton, My Twenty Years of Soccer (1955)

I found it rather embarrassing to read about myself in the gossip columns on the sports pages of the newspapers. This and that club was mentioned as being interested in me, but as far as I was concerned I was a Burnley player and very happy to be one. I also knew that there was a lot more for me to learn, and at Burnley I was learning it. We were a happy club and I found excellent teachers at Turf Moor.

My first intimation as to what was afoot came when I was in the club office by myself one day. Mr. George Allison, then the manager of Arsenal, telephoned and asked for Mr. Alf Boland, the Burnley secretary.

"Mr. Boland is not here at the moment," I replied, "but this is the assistant secretary speaking. Can I help you?"

Imagine my surprise when Mr. Allison replied that he wanted to make an offer for Tommy Lawton and would be telephoning again.

I was in a daze! And the daze got worse as more telephone calls came in. Manchester City, Everton, Newcastle United, Wolves. All were interested in Tommy Lawton-in me!

Arsenal at that time - in fact Arsenal today - were the glamour club of football. Almost every player wanted to play for them, and the thought that they were interested in me made me feel very proud. Little did I know that their bid was to fail and that it was to be many years later before I was to sign on the dotted line for the famous "Gunners".

Actually, I learned later that eight clubs had tried to sign me, but eventually, on 31 December 1936, I was called into the Burnley boardroom and there saw Mr. Will Cuff and Mr. Tom Percy, two Everton directors, with Mr. Theo Kelly, the manager. Mr. Tom Clegg asked me whether I would agree to sign for Everton, and after a conference with grandfather I said I would.

So the deal was completed, and it was agreed that grandfather should accompany me to Everton and have a job on the ground staff.

(4) Len Shackleton, Crown Prince of Soccer (1955)

Favourably situated in the heart of football's most fertile talent belt, Sunderland were attacked for not encouraging young locals, but with a dearth of good ones on the Roker books, players had to be bought for first team duty. There was really no alternative.

Obviously, directors would rather sign a player for £10 than £30,000-ability being on a par-but even the dogmatic disciples of over-rated youth encouragement schemes, like Wolves and Manchester United, find the transfer market a useful medium for occasionally strengthening a team. The recruitment of young players by Wolves has been given a lot of publicity, but it should be remembered that the cheque book also helped to build the successful Molineux side when Bert Williams, Johnny Hancocks and Peter Broadbent were signed. Manchester United, too, were not too youth-minded to feel any pangs of remorse after paying big money for Reg Allen, Johnny Berry and Tommy Taylor.

Sunderland were lavish spenders, but the businessmen on the Board of Directors did not pour money down the drain. They treated it as an investment, and even though the return in the way of dividends may not have been apparent on the playing field, it was certainly reflected at the turnstile.

Whether Sunderland were right or wrong, there is no denying that the buying spree was responsible for Roker Park's boasting one of the highest average attendances in football: in addition, we invariably drew big gates away from home, a state of affairs much appreciated by the clubs we visited.

Similarly, when Tommy Lawton left Chelsea for Third Division Notts County, it was freely prophesied that Notts were committing financial suicide by paying £20,000 for his transfer. Yet there was nothing suicidal about increasing a normal 15,000 gate to an average of 29,000, and smashing the Meadow Lane ground record within a month of Lawton's signing. In soccer, as in any other profession, money attracts money.

(5) Richard Whitehead, The Times (23rd October, 2004)

James also arrived in North London in headline-making circumstances, but only after a prolonged Nicolas Anelka-like sulk had ensured his departure from Preston North End. James was keen to earn more than the £8-a-week maximum wage, but the only way for Arsenal to circumvent the Football League’s strict regulations was for their signing to take up additional employment as a “sports demonstrator” at Selfridge’s on the impressive salary of £250. He was not an instant success — one sarcastic fan sent him a pair of battered child’s football boots with an accompanying note suggesting “it doesn’t matter much what you wear anyhow” — but James quickly became the brains behind a team that dominated domestic football in a fashion that had not previously been seen. Lying deeper than conventional inside forwards, he would spring Arsenal’s rapid breakaways from defence — a tactic that earned them the tag “lucky Arsenal” from disgruntled opposing fans who had frequently seen their team dominate territorially for no tangible reward.

That tactic demonstrated the quality the little man with the commodious shorts shared most with his modern-day counterpart — the ability to hit passes so stunningly beautiful that they could adorn the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

(6) Derby Evening Telegraph (1939)

Arsenal have a big problem. Spending £14,000 on Bryn Jones has not brought the needed thrust into the attack. The little Welsh inside-left is clearly suffering from too much publicity, and is obviously worried. He is a nippy and quite useful inside-left, but his limitations are marked.

(7) Bernard Joy, Forward Arsenal! (1952)

Do we write Bryn Jones down as a gamble that failed, or would he have been a success eventually? The outbreak of war in September 1939 prevented us from ever finding the complete answer. There were signs before then that, as James had done, he was weathering the bad patch which always seems to follow a change of style from an attacking to a foraging inside-forward... My own view, however, is that Jones's modesty was the barrier to achieving the key role Arsenal had intended for him. He could not regard the spotlight as a challenge to produce his best; all the time it irked him, making him self-conscious and uneasy.

(8) Jeff Harris, Arsenal Who's Who (1995)

The Arsenal public realised that the club had not signed a second Alex James. The truth of the matter being that they were two completely different players. At the end of that season he had scored four goals in thirty league appearances. To lay blame on Bryn Jones for the club's lack of success that season was unfair, for in a nutshell, the quiet, modest, self evasive, lonely figure could not cope with the intense pressure of the media spotlight even though his good positional awareness and splendid ball control were there for everyone to behold.

(9) Len Shackleton, Crown Prince of Soccer (1955)

The professional footballer's contract is an evil document. Of that I am certain, so certain, in fact, that I am quite amazed that such a hopelessly one-sided document has survived the tremendous amount of criticism hurled at it by so many people in these enlightened days. Questions have been asked about it in the House of Commons. Public indignation has been voiced, yet the canker remains with us - causing unrest and dissatisfaction to spread through soccer, season after season.

We have often heard such words as serfs or slaves applied descriptively to footballers but until every player in the game has suffered soccer serfdom and raised his voice against it, I am afraid these descriptions will never be taken seriously. Let's face it - the average pro appears to have a pretty good life, with a possible £15 a week wage, plus bonuses, the hope of a £750 benefit (less tax) every five years, a nest egg of nine per cent of all his football earnings when he retires, a house in which to live, and a congenial working day.

That seems reasonable enough up to a point, but on closer examination many flaws may be spotted in the set-up. In the first place, no more than twenty-five per cent of League players draw the maximum £15 wage. Benefits are unheard of in many clubs, while in others they are halved, or even more drastically mutilated at the whim of the directors. Eviction from club houses is automatic when clubs decide to dispense with players' services, and the "pretty good life" is over usually long before a man's fortieth birthday-providing injury has not curtailed it even earlier. It was, in fact, stated once that the average playing life of a professional footballer is seven years, causing more than one of us to comment, "That's a career, that was."

Estimating the average retiring age at 35, the professional footballer finds himself, in the prime of life, jobless, homeless, with a few hundred pounds from the Benevolent Fund and no training for a trade or profession. He sometimes queues up for his turn on the guillotine of a managerial career, or for the menial duties of a team trainer, but there are obviously not enough jobs in football to accommodate every player wishing to stay in the game.

It is all very depressing to anyone hoping for security - and who does not? - but these are the sole "rewards" of the successful players; those who have remained free from injury and been permitted to serve their allotted span as good club servants.

What happens to the unlucky ones? The contract they sign when joining a League club ties them to that particular club for life, if that is the desire of the club, yet it can be terminated without notice if the manager or directors wish it. No more one-sided agreement was ever fashioned in the mind of man.

Professional players are no better than professional puppets, dancing on the end of elastic contracts held securely in the grip of their lords and masters. Sometimes the elastic is severed... always from above, never from below.

Assuming a player has good grounds for wanting a move from his club-his manager may have a particular grudge against him, he might have fallen out with his playing colleagues, or perhaps he detests the town in which he lives-he asks for a transfer. Then the fun starts.

The application may be treated favourably, to all intents and purposes, and the club agree to transfer the player to any other prepared to pay, say, £15,000 for him. To most, that figure is prohibitive, which means our disgruntled soccer star must stay put. On the other hand the Board Room verdict could be, "We are not parting with you," meaning, once again, that he stays where he is.

No other form of civil employment places such restrictions on the movements of individuals, while, at the same time, retaining the power to dismiss them summarily. If a man is able to better himself in a job elsewhere, he should be free to take that job on providing he has fulfilled his contract. It happens in every walk of life, but not in football. Tom Finney, Preston North End's international outside-right, was told he would be a rich man for life if he spent five years playing football on the Italian Riviera. Whether or not Tom was keen to accept this offer-made by an Italian prince - it would surely have been a waste of his time to consider it because Preston would hardly think of allowing him to say "Yes".

Another Italian club, Juventus, were anxious to sign the Teesside marvel, Wilf Mannion, and went so far as to propose to lodge £15,000 in Wilf's banking account on completion of the transfer. Mannion could not capitalize on his ability, because he was tied to Middlesbrough. I could have made a lot of money, much more than is dreamed of in English football, by joining a club in Turkey, but even after the expiry of my seasonal contract, I would not have been permitted to sample this particular Turkish delight.

(10) Nick Varley, Golden Boy (1997)

"In comparison with the average working man," Tommy Lawton said, "you were doing very well. There was a lot of unemployment and even for those in work the average wage was about £1.50 a week. What we earned was a fortune compared to the man in the street, but you had to live up to it. You had to dress correctly, be seen in the right clothes, and not let the club down like that, which cost money. And you knew you wouldn't be doing it forever."

Middlesbrough, while paying the going rate, paid no more, unlike some other clubs. Some offered cash inducements, others jobs of various descriptions - many of them a mirage to fool the authorities - or backing for private ventures that players set up. It was an open secret but only amongst those in the know in the game. When Sunderland, the famous Bank of England club, were hauled up a couple of years later for practices which made them look like BCCI, fans were shocked at the under-the-counter payments, but few leading players, managers or officials were surprised.

Wilf found out about such scams on his trips with England, learning from other players what their fringe benefits were, how their clubs had 'helped' them to set up businesses or find a part-time, but lucrative, job. It was one of the reasons why clubs were not so keen on international call-ups for players - it gave them too much of an idea of their own worth.

"The chairmen didn't like players coming to play international football," Sir Walter Winterbottom admits, "because it meant them getting in touch with other professionals and hearing of what the others' deals were. After playing for England, they often went back and demanded more."

They might even ask for a transfer if they were really dissatisfied, but that's where the contrast with today's stars was even greater than on wages. Signing for a club could be a life sentence, for once a player put his name on the dotted line he belonged to the club. At the end of each subsequent season all they had to offer was a new one-year contract which, as long as the club offered maximum terms, the player was bound to accept. The only alternative - to reject the contract - would mean he could be kept out of the game. The club was allowed to keep his registration and refuse a transfer.

On the other hand, if clubs wanted to sell, they could so at any time. The only say the players got was in accepting or declining the prospective buyer found by the club. Even if the answer was yes, no matter how big the fee involved, the player's cut was the same: a £10 signing-on fee.