Sunderland Football Club : 1879-1939

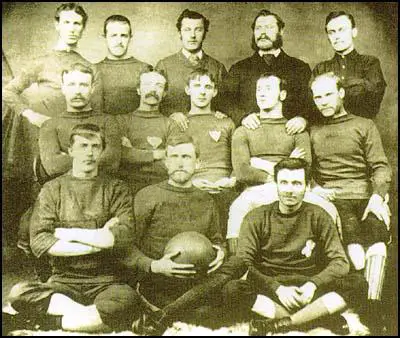

James Allan arrived in Sunderland from Scotland to teach at Hendon Board School in 1877. He had developed an interest in football while at Glasgow University but discovered that rugby was the predominant winter team sport in the North-East. As Roger Hutchinson points out in Into the Light (1999) "Allan uncovered a group of other teachers in the area who shared his interest in righting this wrong, and at a meeting in Norfolk Street in the October of 1879 the Sunderland and District Teachers' Association Football Club was formed."

The team originally played at Blue House Field that was close to the Hendon Board School where James Allan was employed. The captain was Robert Singleton, the headmaster of Gray School in Sunderland. Other school teachers in the side included John Graystone and Walter Chappell.

Allan and his friends rented the ground at Hendon for £10 a year. They also had to pay the travelling cost of taking a team to away games throughout the North-East. At a meeting in October 1880 they discussed the possibility of closing the club. However, it was eventually decided to raise the money by opening it up to non-teaching members. As a result the club changed its name to Sunderland Association Football Club.

As the author of Sunderland: The Official History points out: "The club was formed not by shipbuilders or miners, but by school teachers, local school master James Allan having taken the initiative in organising such a venture. More surprisingly still, the teachers not only formed the club, but made up the entire team too, and the club's original name - Sunderland and District Teachers' Association Football Club - reflected this."

At the time rugby and cricket were Sunderland's main sports. Another problem was that there were only three other football teams in the whole of County Durham. This meant that the team had to do a lot of travelling to get games. This included matches against clubs such as Sedgefield, Bishop Middleham, Ferryhill, Ovingham and Newcastle Rangers.

James Allan was a talented centre-forward with a good goalscoring record. In 1883 Allan's goals helped Sunderland reach the final of the Northumberland & Durham Cup. The following year the club played Darlington in the first final of the Durham Cup. Sunderland won 4-0 but Darlington complained that the 2,000 fans were guilty of intimidating their players. The Football Association ordered the final to be replayed and sent Major Francis Marindin to referee the game. This time Sunderland won the game 2-0.

The following season Sunderland entered the FA Cup for the first time. In the first round the club lost 3-1 to Redcar. That season James Allan was one of the six Sunderland players selected for the Durham County side which played Northumberland.

On 20th December, 1885, Sunderland beat Castletown 23-0 in the first round of the Durham Association Challenge Cup. James Allan, who played on the left-wing, scored 12 of the goals. This remains a Sunderland club record.

In an attempt to improve the team Sunderland began recruiting players from Scotland. The Football Association decided that professionalism should be allowed, but with restrictions. Any professionals had either to have been born in the town they represented, or to have lived within six miles of their club's headquarters for the previous two years.

In 1887 Sunderland beat Middlesbrough 4-2 in an early round of the FA Cup. Middlesbrough protested that three of Sunderland's players (Monaghan, Hastings and Richardson) were living in Scotland and was lodged at the Royal Hotel at the club's expense. In January 1888, the Football Association examined the Sunderland books and discovered "a payment of thirty shillings in the cash book to Hastings, Monaghan and Richardson for train fares from Dumfries to Sunderland". Sunderland was kicked out of the FA Cup and ordered to pay the expenses of the inquiry. The three players concerned were each suspended from football in England for three months.

James Allan, who disliked the idea of recruiting professional players, resigned from the club. On 13th March 1888 he organized a meeting at the Empress Hotel. The meeting decided to create Sunderland Albion. Allan managed to persuade six first-team players from Sunderland to join him.

Sunderland and Sunderland Albion now became bitter rivals. The two clubs were drawn together in the 1888-89 FA Cup. However, Sunderland withdrew rather than allow Albion to benefit from the increased gate receipts.

On 2nd March, 1888, William McGregorcirculated a letter to Aston Villa, Blackburn Rovers, Bolton Wanderers, Preston North End, and West Bromwich Albion suggesting that "ten or twelve of the most prominent clubs in England combine to arrange home and away fixtures each season."

John J. Bentley of Bolton Wanderers and Tom Mitchell of Blackburn Rovers responded very positively to the suggestion. They suggested that other clubs should be invited to the meeting being held on 23rd March, 1888. This included Accrington, Burnley, Derby County, Notts County, Stoke, Wolverhampton Wanderers, Old Carthusians, and Everton should be invited to the meeting.

The following month the Football League was formed. It consisted of six clubs from Lancashire (Preston North End, Accrington, Blackburn Rovers, Burnley, Bolton Wanderers and Everton) and six from the Midlands (Aston Villa, Derby County, Notts County, Stoke, West Bromwich Albion and Wolverhampton Wanderers). The main reason Sunderland was excluded was because the other clubs in the league objected to the costs of travelling to the North-East. McGregor also wanted to restrict the league to twelve clubs. Therefore, the applications of Sheffield Wednesday, Nottingham Forest, Darwen and Bootle were rejected.

Preston North End won the first championship that year without losing a single match and acquired the name the "Invincibles". Preston also won the league the following season. This time it was much closer as they only beat Everton by one point.

Sunderland continued to do well in friendly games. During the 1889-90 season they beat league teams Blackburn Rovers (1-0), Bolton Wanderers (3-2), Everton (2-0) and Notts County (2-1). They also held league champions, Preston North End, to a 1-1 draw. Sunderland also won the Durham Association Challenge Cup for the fourth time in five years.

Sunderland once again applied to join the Football League. The club also offered to pay towards the travelling costs of opponents in order to compensate for the extra travelling they would have to do. As a result of this application, Sunderland replace Stoke in the league. Sunderland made their intentions clear by erecting a sign outside the ground stating, “We have arrived and we’re staying here.”

Ted Doig joined Sunderland and his first game for his new club was on 20th September, 1890. As he was not officially registered as a Sunderland player the club suffered a deduction of two points. Sunderland finished in 7th place in the league (it would have been 5th if they had not suffered the points deduction. Sunderland also reached the semi-final of the FA Cup. Aston Villa won the game 4-1.

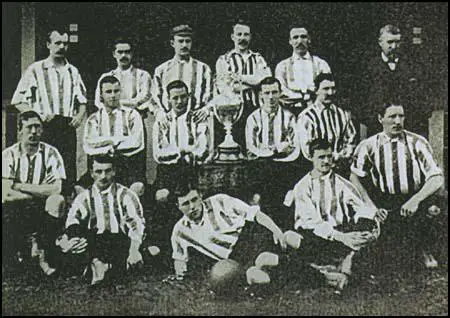

The following season Sunderland won the Football League championship and reached the semi-final of the FA Cup. William McGregor described Sunderland as having a "talented man in every position" and as a result they acquired the name the "Team of All Talents".

Sunderland retained the championship in 1892-93 and were runners-up to Aston Villa in the 1893-94 season. Sunderland were also champions in 1894-95. Ted Doig did not miss a Football League or FA Cup game between 20th September 1890 and 9th September 1895.

Alf Common joined Sunderland in 1900. In the 1900-01 season Sunderland finished 2nd to Liverpool in the First Division championship. Common scored 5 goals in 20 appearances that year. However, he was considered one of the best young players in England and Sheffield United paid Sunderland £350 for his services. He was a great success at his new club and in 1904 Sunderland bought him back for a new record transfer fee of £520.

Alf Common only played in 21 games before he was on the move again. In February, 1905, Middlesbrough, who were in danger of being relegated from the First Division, purchased Common for the record breaking fee of £1,000. One journalist described the transfer of Common as "flesh and blood for sale". Another sports writer wrote: "We are tempted to wonder whether Association football players will eventually rival thoroughbred yearling racehorses in the market."

The reason for the sale was that Sunderland believed they had an able replacement in the nineteen year old George Holley had already been scoring plenty of goals for the reserves. Playing at inside-left, Holley soon became the club's top goalscorer.

In January 1908 Sunderland signed Leigh Roose. He was brought in to replace Ted Doig who had moved to Liverpool. Roose was considered the best goalkeeper in Britain and the football journalist, James Catton, described Leigh Roose in Athletic News as "the Prince of Goalkeepers". Frederick Wall, the Secretary of the Football Association described Roose as "a sensation... a clever man who had what is sometimes described as the eccentricity of genius. His daring was seen in the goal, where he was often taking risks and emerging triumphant." Rouse was an entertainer, who carried out pranks to get laughs. This included sitting on the crossbar at half-time.

Rumours began to circulate that his new club were making illegal payments in order to gain Roose's services. As an amateur he was only allowed to be paid expenses. The Football Association asked Roose to compile a list of each individual expense claim made in the 1907-8 season. Roose made a joke of the situation by including "Pistol to ward off opposition - 4d. Coat and gloves to keep warm when not occupied - 3d. Using the toilet (twice) - 2d." Sunderland insisted that they only paid Roose his travel expenses. Unable to prove otherwise, the Football Association dropped its case against the club.

In 1908 Sunderland signed Charlie Thomson from Heart of Midlothian. A centre-half, Thomson was also captain of the Scotland international team. He joined a side that included Britain's best goalkeeper, Leigh Roose and one of the countries best goalscorers, George Holley. That season Sunderland finished 3rd in the First Division. Their local rivals Newcastle United won the title with 53 points. However, Sunderland had the satisfaction of beating Newcastle 9-1 at St. James' Park with Holley scoring a hat-trick. James Catton wrote in the Athletic News: "When some beardless boys have become grandfathers, they will gather the younger generation round them and tell a tale of Tyneside, about the stalwart Sunderland footballers who travelled to St James' Park and thrashed the famous Novocastrians as if they had been a poor lot of unfortunates from some home for the blind. The greatest match of this season provided the sensation of the year and we shall have to turn back the days to when the game was in its infancy for a parallel performance. Never have I watched forwards who have seized their opportunities with more eagerness and unerring power."

Leigh Roose was especially popular with female fans. The Daily Mail dubbed him "London's most eligible bachelor". In 1909 he began a relationship with Marie Lloyd, the star of the country's music halls. It caused a stir as Lloyd was married at the time to the singer Alec Hurley. Roose was often seen at Lloyd's concerts and she would always be in the crowd when Sunderland played in London.

Roose become a strong favourite with the Sunderland fans. They liked the way he set up attacks by running out to the half-way line. Roose told a journalist that he was surprised that not more goalkeepers did not follow his example: "The law states that any (goalkeeper) is free to run over half of the field of play before ridding themselves of the ball. This not only helps to puzzle the attacking forwards, but to build the foundations for swift, incisive counter-attacking play. Why then do so few make use of it?"

George Holley, who played for Sunderland with Leigh Roose later explained why this strategy was not followed by other goalkeepers. "He was the only one who did it because he was the only one who could kick or throw a ball that accurately over long distances, giving himself time to return to his goal without fear of conceding."

Several clubs complained to the Football Association about Roose's strategy. Several committee members felt that Roose was ruining the game as a spectacle by his ability to break up creative and attacking play. However, they could not agree about what to do about it.

Some journalists were critical of the way Roose played. The Athletic News published an article following Sunderland's 4-1 win over Liverpool in September 1909: "The great man of the side was Roose. His one failing is his habit of running out with the ball, a failing which I suppose will be with him (for the rest of his career), but he is a brilliant goalkeeper without doubt."

Leigh Roose did sometimes give away goals by using this strategy. In October, 1909, Ernest Needham, who was playing in goal for Sheffield United against Sunderland, scored with a long kick after Roose advanced too far out of his goal. Sunderland came to the conclusion that Roose would be unable to regain full fitness and decided not to employ him for the 1910-11 season.

In March 1911, Sunderland paid a transfer fee of £1,200 for Charlie Buchan. This beat the £1,000 paid by Middlesbrough for Alf Common in 1905. The Sunderland fans did not immediately take to Buchan and he suffered a great deal of barracking from the Roker Park crowd. Buchan asked to be dropped from the side but Bob Kyle, the manager, refused. After one game in November, 1911, Buchan told Kyle: "I'll never kick another ball for Sunderland." Kyle persuaded Buchan to play one more game for the club. He agreed and scored two goals in the 3-1 victory. Buchan recalled that this was the turning point and never again got "the bird" from the crowd.

Charlie Buchan gradually developed a very good partnership with George Holley, Sunderland's leading goalscorer. Buchan later argued that in a game against Bradford City, Holley performance was the best he ever saw by an inside-forward. "He scored a magnificent hat-trick, running nearly half the length of the field each time and coolly dribbling the ball round goalkeeper Jock Ewart before placing it in the net."

George Holley also supplied Buchan with the passes for a large percentage of the goals he scored for Sunderland. In one game he scored five goals against Kenneth Campbell, the Scottish international goalkeeper, who at the time played for Liverpool. "Four of them I just touched into the net. Holley had beaten the defence and even drawn Campbell out of position before giving me the goals on a plate."

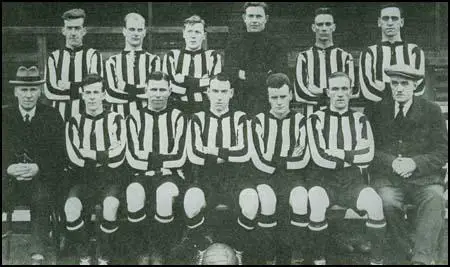

At the beginning of the 1912-13 season Bob Kyle paid £3,000 for two defenders, Charlie Gladwin and Joe Butler. This was a large sum of money. At the time, the record transfer fee was the £1,800 paid by Blackburn Rovers to West Ham United for prolific goalscorer Danny Shea.

Kyle also purchased James Richardson from Huddersfield Town to play alongside Charlie Buchan, George Holley, Henry Martin and Jackie Mordue, in the forward line. The defence was made up of Joe Butler in goal, Charlie Gladwin and Albert Milton, full backs, with Frank Cuggy, Charlie Thomson and Harry Low playing in the half-back line.

The season started badly and by mid-October Sunderland was bottom of the First Division table with only two points in seven games. However, the new players gradually integrated into the side and the club moved up the table by winning the next five games. By the end of December 1912 Sunderland was challenging for the title with Charlie Buchan, George Holley and Jackie Mordue, all having scored 12 goals each. However, according to Buchan it was a defender, Charlie Gladwin, that was the real reason why Sunderland played so well. "He stabilized the defence and gave the wing half-backs Frank Cuggy and Harry Low the confidence to go upfield and join in attacking movements. Sunderland became a first-class team from the moment he joined the side."

January 1913 saw Sunderland beat Arsenal (4-1), Tottenham Hotspur (2-1), Chelsea (4-0), Middlesbrough (2-0) and Derby County (3-0). It was now clear that only Aston Villa could deprive Sunderland of the First Division championship.

Sunderland also had a good FA Cup run. On the way to the final Sunderland beat Manchester City (2-0), Swindon Town (4-2), Newcastle United (3-0) and Burnley (3-2). The final was played in front of 120,000 at Crystal Palace against Aston Villa, their rivals for the league championship. Early in the game, Clem Stephenson told Charlie Buchan that the previous night he had dreamt that Villa won the game 1-0 with Tommy Barber scoring the only goal with a header.

The game included a running battle between Charlie Thomson, the Sunderland centre-half and Harry Hampton, Aston Villa's tough centre-forward. Hampton had a reputation for being rough on goalkeepers. One local commentator reported that: "Thomson was the centre of one of the main talking points of the game after a thrilling duel with the Villa forward Hampton. He had scored for England against Thomson's Scotland by charging the keeper over the line. Charlie was determined this was not going to happen during the Cup Final, so early on he laid Hampton out to let him know who was boss!"

Thomson decided to protect his goalkeeper, Joe Butler, by making a heavy challenge on Hampton early on the game. A journalist reported: "Thomson had great difficulty in holding the nippy Villa inside forwards and fouled Hampton so badly that the centre forward was prostrate for several minutes. Later in the game Hampton viciously retaliated by kicking Thomson when he was on the ground and it was regrettable that the game was marred by such unseemly incidents."

Charlie Buchan recorded in his autobiography, A Lifetime in Football,: "Thomson and Hampton soon got at loggerheads and rather overstepped the mark in one particular episode. Though neither was sent off the field, they each received a month's suspension." The referee, Albert Adams, was also banned for a month for failing to maintain order. Adams was never asked again to officiate in another professional football game.

Just before the end of the first-half, Clem Stephenson was brought down in the 18-yard box by Charlie Gladwin. However, Charlie Wallace, dragged his penalty shot wide of the post.

Soon after the interval Harry Hampton had a goal disallowed for offside. This was followed by Sam Hardy, the Aston Villa goalkeeper being injured after a clash with Henry Martin and for a time Sunderland played against ten men. Although they hit the upright twice and had one shot cleared off the line, they could not score against Jim Harrop, the Villa centre-half, who had replaced Hardy as goalkeeper.

With 15 minutes remaining Charlie Wallace took a corner-kick. He scuffed the ball and it came into the box at waist height. With the Sunderland defence expecting a high-ball, Tommy Barber was able to ghost in from midfield and head it into the net. Stephenson's dream had come true.

Four days later Sunderland played Aston Villa in the league. Sunderland was only two points in front of their rivals with only three games to go, they had to avoid defeat in order to make sure they won the First Division championship. Over 70,000 watched Harold Halse score the opening goal. However, Sunderland fought back and Walter Tinsley converted a pass from Henry Martin to earn a 1-1 draw.

Sunderland won their last two matches against Bolton Wanderers (4-1) and Bradford City (1-0) to win the title by four points from Aston Villa. Charlie Buchan finished as the club's top scorer with an impressive 32 goals in 46 games.

By the time the Football League resumed after the First World War, several of its best players were past their best. In both the 1920-21 and 1921-22 seasons the club finished in 12th place.

Bob Kyle completely rebuilt the playing squad and by the 1922-23 season Charlie Buchan was the only survivor of the Sunderland team that won the Football League title in the 1912-13 season. Sunderland had a much better season and finished in second place, six points behind Liverpool. Buchan scored 30 goals that made him the top scorer in the whole of the First Division.

In 1931 Johnny Cochrane, the manager of Sunderland, signed the 17 year old Raich Carter. He joined a team that included players such as Alex Hastings, Patsy Gallacher, Bob Gurney and Jimmy Connor.

In the 1934-35 season Sunderland finished as runners-up to Arsenal in the First Division of the Football League. The forward line included Raich Carter, Patsy Gallacher, Bob Gurney and Jimmy Connor. According to Charlie Buchan Carter was the star of the Sunderland forward-line. He wrote: "His wonderful positional sense and beautifully timed passes made him the best forward of his generation."

Despite only being 23 years old, Raich Carter was made captain of the Sunderland team as a result of an injury to Alex Hastings. In the 1935-36 season Carter was in great form that season scoring 24 goals in his first 22 games and Sunderland built up a good lead in the championship.

On 1st February 1936, Sunderland played Chelsea at Roker Park. According to newspaper reports it was a particularly ill-tempered game and Chelsea's Billy Mitchell, the Northern Ireland international wing-half, was sent off. The visiting forwards appeared to be targeting Jimmy Thorpe, the Sunderland goalkeeper, and he took a terrible battering during the match. After the game Thorpe was admitted to the local Monkwearmouth and Southwick Hospital suffering from broken ribs and a badly bruised head. James Thorpe died on 9th February, 1936.

Sunderland was devastated by the death of their 22 year-old goalkeeper. However, they continued their good form and by 13th April, 1936, the club only needed to draw at Birmingham City to clinch the title. The result was a 7-2 victory. That season Sunderland became the first club to score over 100 goals in a season. Raich Carter was joint top scorer with Bob Gurney with 31 goals.

In the 1936-37 season Sunderland could only finish 8th in the Football League. However, they had a great FA Cup run beating Luton Town (3-1), Swansea (3-0), Wolverhampton Wanderers (4-0) and Millwall (2-1) to reach the final against Preston North End.

The match took place on 1st May 1937. In the 38th minute, Hugh O'Donnellpassed to his brother, Frank O''Donnell, who scored the opening goal. Preston North End held the lead until early in the second-half. In the 52nd minute Eddie Burbanks took a corner. Carter headed the ball to Bob Gurney, who back-headed the ball into the net.

Frank Garrick, the author of Raich Carter: The Biography, described what happened next: "In the 72nd minute, Raich Carter was given a chance to atone for his missed chance. He was in the inside-left position when a bouncing pass came over from Gurney to his right. Carter beat the fullback, raced the goalkeeper to the ball and lobbed it out of his reach into the net. Both players finished in a heap on the ground and Sunderland were in the lead. Carter was mobbed by his teammates and the cheering lasted for several minutes."

Six minutes later, Patsy Gallacher created a third goal with a skilfully judged pass to Eddie Burbanks who shot home from a narrow angle. Carter had led Sunderland to its first FA Cup final victory.

Primary Sources

(1) Philip Gibbons, Association Football in Victorian England (2001)

Like many teams in the north of England, Sunderland's early origins owed much to a Scottish influence when, during 1877, James Allan arrived in the area from Glasgow University to take up a teaching position. He introduced the Association game to his school colleagues, which eventually led to the formation of the Sunderland and District Teachers Association with their home ground based at Blue House Field, Hendon.

(2) Paul Davis, Sunderland A. F. C. : The Official History (1999)

John "Teddy" Doig succeeded the long serving "Stonewall" Kirtley as Sunderland's goalkeeper. Kirtley made a number of blunders in the opening games, and was blamed for a heavy defeat against Wolves. His replacement was brought in rather quickly though, and was unregistered in his first match and Sunderland were deducted two points as a consequence. Indeed, the whole manner of his arrival was surrounded in controversy, for he had signed for Blackburn but then walked out on them after one game - perhaps Sunderland had made him a better offer - and was duly suspended.

(3) James Catton, Athletic News (5th December, 1908)

When some beardless boys have become grandfathers, they will gather the younger generation round them and tell a tale of Tyneside, about the stalwart Sunderland footballers who travelled to St James' Park and thrashed the famous Novocastrians as if they had been a poor lot of unfortunates from some home for the blind. The greatest match of this season provided the sensation of the year and we shall have to turn back the days to when the game was in its infancy for a parallel performance. Never have I watched forwards who have seized their opportunities with more eagerness and unerring power.

(4) Sunderland: The Official History (1999)

The game got underway in misty conditions with a light rain. The first half was a normal enough affair, Sunderland taking an cash lead on nine minutes through simple tap in by Hogg. The game erupted on half time though, as Newcastle were awarded a controversial penalty when Thomson was adjudged to have hand balled. The Sunderland players were incensed with the referee but their protests made no difference. Shepherd smacked home the spot kick and made it 1-1 at the interval.The Sunderland placers were livid and came out like men possessed after the half time break. Attacking the Leazes End, they set about destroying this Championship side. A further eight goals were smashed in during an amazing half hour period, six of them coming in only ten minutes!

Holley got the hall rolling just three minutes after the restart, the striker taking advantage when a brilliant run and cross from Bridgett caused confusion in the Newcastle defence. Ten minutes later, the Lads' increasing dominance of the game paid further dividends, as Hogg smashed his second of the game to make it 3-1.

By now, Sunderland were clearly on top, but a devastating ten minute spell was about to stun the whole football world. In the 63rd minute, Holley cleverly jinked past a couple of defenders to make it 4-1, and four minutes later completed his hat-nick with a thunderbolt shot. Two minutes later, Bridgett won a battle for the ball with Whitson before rounding him and making it 6-1.

(5) Sunderland: The Official History (1999)

The crowd created an atmosphere that even made our captain Charlie Thomson "excitable". Thomson was the centre of one of the main talking points of the game after a thrilling duel with the Villa forward Hampton. He had scored for England against Thomson's Scotland by charging the keeper over the line. Charlie was determined this was not going to happen during the Cup Final, so early on he laid Hampton out to let him know who was boss! Hampton was later to retaliate by kicking Thomson when he was on the ground, but amazingly neither were sent off, although they were both suspended for the opening month of the next season!"

(6) Spencer Vignes, The Remarkable Life and Death of Leigh Richmond Roose (2007)

His (Leigh Roose) style of play was also completely different from any other goalkeeper of the time. Here was someone prepared to take on menacing centre forwards at their own game, rushing out to break up opposing attacks by whatever means possible - diving on the ball, kicking it clear, or resorting to more brutal means, such as clattering into a player with his six-foot frame. Up until then, this just hadn't happened. Goalkeepers were supposed to stay on or at least near their goal line at all times, daring to venture out only on rare occasions. Not Leigh, who spent long periods of each match playing in the position known today as 'sweeper', tidying up every loose ball in the gap immediately behind his defenders.... As George Holley put it, "He was the mould from which the rest were created."

Leigh's reflexes were astonishing, and he could punch the heavy brown footballs used in Edwardian days further than many of his opponents were able to kick it. Then there was his very own secret weapon, bouncing the ball all the way up as far as the halfway line before punting it towards the opposition goal with one of his monstrous trademark kicks. This was perfectly within the letter of the law, though few goalkeepers risked doing it for fear of either leaving their goal unattended or being steamrollered by a centre forward. It became a highly effective, direct way of launching attacks and Leigh used it to his side's advantage whenever possible....

One aspect of the game that had remained constant over the years was Leigh's attack-minded style of goalkeeping, running out as far as the halfway line while in possession of the ball before releasing it with one giant kick or throw. Although other keepers had by now become more adventurous in their play, using the whole of the penalty area rather than staying routed to their line waiting for a shot, Leigh was still in a world of his own when it came to using an entire half.

(7) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

The crowd began to barrack me and I must admit I deserved it. I asked to be dropped from the side but the manager would not listen.

Finally after one game in mid-November when the crowd had, with every reason, been noisily expressive about my play, I stormed into the dressing-room and declared in a loud voice: "I'll never kick another ball for Sunderland."

Unfortunately, the local reporter heard me. In the evening paper, there were bold headlines on my statement. On Monday morning there were more reports.

Though I received hundreds of letters urging me to carry on, I packed up my bag and went home to Woolwich.

On the following Saturday, Sunderland were to play Woolwich Arsenal at the Manor Field, which was only about half-a mile from my home. I did not expect to play.

But two days before the game, Manager Kyle came to the house and, after a talk with my father, persuaded me to turn out. "Do your best to show the locals you can do it," he said, "and if you fail, we can talk about it afterwards."

I played, scored a couple of goals in a 3-I win for Sunderland, and felt much better afterwards. I stayed the following week at home and somehow felt a lot stronger.

That was the turning point. I returned to Sunderland and began to put on weight. I quickly ran up to 12st. 8lb. - my playing weight for the rest of my days - and struck a little form.

No longer did I get "the bird" from the crowd. They were very kind to me, as they were for the fourteen and a half years I spent with the club.

During this testing time I owed a debt of gratitude to trainer Billy Williams that I never repaid nor ever could repay. He looked after me like a father. If I got the slightest knock he came round to my house to attend to it at once. He also nursed me during training hours, saw that I did not overtax my strength and gave me tonics when he thought them necessary. At the time it was very often.

After I had been a few weeks at Sunderland, he noticed that I smoked quite a number of cigarettes during the day. Cigarettes were his pet aversion.

One day he handed me a new pipe, a pouch full of tobacco and a box of matches. "I want you to promise me that you will give this a fair trial and leave cigarettes alone," he said.

Taken by surprise, I gave him my promise. I smoked nothing but a pipe from that day until just over three years ago when I parted company with my teeth.

Trainer Williams was a strict disciplinarian. One day I arrived a minute or two after the time we were due to report for duty. There he stood at the door waiting for me to enter. Without a word, he pulled his watch from his pocket, looked at it then put it back. I felt very guilty. A few seconds later, he pulled out his watch again and repeated the performance. It made me feel so small that I vowed I would never be late for training again. I kept my vow.

While we were in the dressing-rooms during training hours or on match days, smoking was strictly forbidden. If a club director came into the room smoking, he was quickly ordered out. Williams was king of his own castle.

(8) John Hudson, Sunderland: The Official History (1999)

The date was 7th December, 1912, the score 7-0...For Charlie Buchan it was a personal triumph. Strangely, the man of the match was Liverpool's goalkeeper Campbell, who was outstanding; but for him it would have been double figures for Sunderland. There were clear opportunities early on for both sides, but it was Sunderland who took the lead. From a quick break Hall ran away, laid off the ball to Buchan, who with a swift low shot opened the scoring... Buchan coolly slotting home a cross from Martin. After the interval the Lads were straight on the attack looking for more goals. Nevertheless, it took until 21 minutes after break for the fifth goal, Buchan once again the man, registering his hat trick after converting a left-wing cross. Five minutes later and Buchan was beginning to make it a one-man show. Mordue took a corner, flighting it in beautifully, and after Campbell parried a shot, Buchan lashed the loose ball into the back of the net for the sixth. Having totally outclassed the opposition, we now took it easy, but with only four minutes left Holley strolled down the wing and crossed to Buchan who put in his fifth goal, and Sunderland's seventh.

(9) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

Bob Kyle went into the transfer market. He bought Charlie Gladwin, six-foot-one-inch, fourteen stone Blackpool right-back, and Joe Butler, Stockport County goalkeeper.

Local people thought he must have gone crazy to pay something like £3,000 for the two. In those days, when the record transfer fee was £1,850, paid by Blackburn Rovers to West Ham United for inside-right Danny Shea, it was a lot of money, worth, I should say, ten times the amount today.

It was money well spent. From the moment Gladwin and Butler joined the side, Sunderland went ahead and became the finest team I ever played for, and one of the best I have ever seen.

Not only did we win the League Championship with a record number of points, but we nearly brought off the elusive League and Cup double, accomplished only by Preston North End and Aston Villa.

We reached the F.A. Cup final, only to be beaten by Aston Villa at the Crystal Palace before a record crowd.

Joe Butler, short and sturdy, very like Bill Shortt, the Plymouth Argyle and Welsh international goalkeeper, was reliable rather than spectacular, but it was Gladwin who revitalized the side.

There are people who say that no one player can make a poor side into a great one, and that there isn't one worth a £3,000 transfer fee. Gladwin proved they are wrong.

He used his tremendous physique to the fullest advantage. Before a game he would say: "When there's a corner-kick against us, all clear out of the penalty-area. Leave it to me."

We invariably did. But one day Charlie Thomson, our captain and centre-half with the big, black, flowing moustache, forgot the instruction.

The ball came across the goal ... Gladwin, as usual, got it and his mighty clearance struck Thomson full in the face. He went down like a log.

That was just before half-time. Thomson was brought round in time to take his place after the interval, but when he came out he joined the other side and started to play against us. He was suffering from concussion.

Gladwin was one of those full-backs who never read a newspaper or knew whom he was playing against. He was a natural player who went for the ball-and usually got it. Before a game, a colleague would say to him: "You're up against Jocky Simpson today so you're for it." All Gladwin would say was: "Who's Jocky Simpson?" At that time, Simpson was as well-known and as famous as Stanley Matthews is today.

At other times, one would say to Gladwin: "You must be on your best behaviour, Tityrus is reporting the game."

Now Tityrus, the mighty atom Jimmy Catton, was the out standing sports writer of his day and editor of the Athletic News, known then as the "Footballers' Bible".

Yet Gladwin's only remark was: "Who's Tityrus"?

Before every game, Gladwin pushed his finger down his throat and made himself sick. It was his way of conquering his nerves. Yet on the field he was one of the most uncompromising and fearless players I have known.

He stabilized the defence and gave the wing half-backs Frank Cuggy and Harry Low the confidence to go upfield and join in attacking movements.

Sunderland became a first-class team from the moment he joined the side. He was worth his weight in gold; yes, more than the £34,500 paid for Jackie Sewell.

With Gladwin and Butler consolidating the defence, Sunderland gradually crept up the League table until we knew we had a chance of winning the championship-there was only one team we feared, Aston Villa.

(10) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

A week before the final we got a shock - George Holley, our great inside-left, received a severe ankle injury which threatened to keep him out of the game. After a test on the morning of the final, it was decided to play him.

It proved to be the most sensational of all the Crystal Palace finals. It was crowded with incidents, some of which are better forgotten.

First, there was the trouble between Charlie Thomson, our centre-half and Harry Hampton, Villa's dynamic centre-forward, the terror of goalkeepers. It was Hampton, who, in 1913, won an international for England at Stamford Bridge by charging Brownlie, the Scottish goalkeeper, with the ball in his arms, into the net.

Thomson and Hampton soon got at loggerheads and rather overstepped the mark in one particular episode. Though neither was sent off the field, they each received a month's suspension; the first month of the following season.

There was also an injury to Villa goalkeeper, Sam Hardy, which kept him off the field for about twenty minutes. The game was held up for seven minutes, making it the longest final, apart from extra-time, in the history of the event.

Hardy, I consider the finest goalkeeper I played against. By uncanny anticipation and wonderful positional sense he seemed to act like a magnet to the ball.

I never saw him dive full length to make a save. He advanced a yard or two and so narrowed the shooting angle that forwards usually sent the ball straight at him.

When the game was resumed, with Villa centre-half Jim Harrop in goal, we peppered away at the Villa goal. We hit the upright twice, but simply could not get the bail into the net.

Then, midway in this half, with Hardy back in goal, Villa forced a corner-kick on the right. Charlie Wallace took it and sent the ball waist-high somewhere about the penalty-line, a bad kick really.

Tom Barber, Villa right-half, dashed forward and got his head to the ball. As our defenders stood apparently spellbound the ball passed slowly between them into the corner of the net.

This amazing goal was enough to give Villa the Cup and made a dream come true for Clem Stephenson, Villa inside-left, of the stocky frame and north-country accent.

When we were lined up for a throw-in soon after the game started, Clem said to me: "Charlie, we're going to beat you by a goal to nothing."

"Oh," I replied, "what makes you think that?"

"I dreamed it last night," said Clem "also that Tom Barber's going to score the winning goal." I could not help but think of a song at the time which had these words: "Dreams very often come true."

A great schemer and tactician, Clem brought the best out of his colleagues by his accurate, well-timed passes. He was by no means fast but made the ball do the work.

He was the general who led the brilliant Huddersfield team to three successive League championships.

(11) The Sunderland Echo (24th April 1928)

Young Carter, the Hendon schoolboy was, I am told, the best forward on the field in the match against Scotland on Saturday at Leicester which England won five to one.

(12) The Sunderland Echo (7th November 1932)

Carter is improving every time he turns out with the seniors. I think he should be brought on slowly and he should not be overworked. It is many years since I saw a more promising pure footballer.

(13) Raich Carter, statement published in The Sunderland Echo (30th April 1937)

I think we will win. I am proud to captain the Sunderland team in the final, and the finest wedding present I could possibly get would be to receive the cup from His Majesty tomorrow and to bring it to Sunderland on Monday. Sunderland expects, and our boys won't fail for the want of trying.

(14) Frank Garrick, Raich Carter (2003)

From the kick-off it was clear that the players were suffering from nerves. In the opening exchanges passes regularly went astray. The Sunderland teamm took longer to settle down than Preston but gradually they came more into the game. Bob Gurney missed a difficult chance from an Eddie Burbanks cross and then put the ball in the net only to be judged offside. In the 38th minute, Frank O'Donnell combined with his brother Hugh, on the Preston left wing, to split the Sunderland defence and score the opening goal. This meant the Preston striker had scored in every round in the competition. More significant to Sunderland players and supporters was the knowledge that no team in a Wembley final had wonn the cup having conceded the first goal. However, this was the fourth time in five ties that Sunderland had fallen behind, so they knew they could come back. At half-time the score remained 1-0. In the dressing room one player claimed that O'Donnell must be stopped at alll costs. This provoked Raich Carter into a forceful response: "We have got to be more in the game. We have got to make the ball work more, find the man more. Let's play football as we can play it, and we shall be alright." It is interesting that there does not seem to have been any significant comment from the manager or the trainer.

With the captain's words in their ears, the Sunderland team equalised within six minutes of the restart. Burbanks took a corner which Carter headed forward to Gurney who had his back to the goal and back-headed the ball into the net. This goal further revived the Sunderland players, confidence flowed and the football was transformed. Sunderland were really playing now and they laid siege to the Preston goal. Next Carter missed what the Echo described as "an absolute sitter" when, on receiving a pass from Burbanks, he topped his shot into the side netting. The moan from around the stadium reinforced Carter's sense of disappointment. A chance had come and he had missed it.

At the other end of the pitch one of the great battles of the match between Sunderland's centre-half Bert Johnston and the Preston number nine O'Donnell continued to rage. Johnston had only prevented his opponent from scoring a second goal by bringing him down. The referee administered a stern warning but no caution or dismissal as would be the case today. As the duel continued Johnston gradually achieved mastery. At the same time Charlie Thomson, in midfield for Sunderland, was playing more and more impressively. He gave support to the defence and was involved in the moves which led to the goals.

In the 72nd minute, Raich Carter was given a chance to atone for his missed chance. He was in the inside-left position when a bouncing pass came over from Gurney to his right. Carter beat the fullback, raced the goalkeeper to the ball and lobbed it out of his reach into the net. Both players finished in a heap on the ground and Sunderland were in the lead. Carter was mobbed by his teammates and the cheering lasted for several minutes. Choruses of the song "Blaydon Races" echoed around the stadium.

(15) Michael Parkinson, Football Daft (1968)

Raich Carter strode alone on to the field some time after the other players, as if disdaining their company, as if to underline that his special qualities were worthy of a separate entrance... It seemed that he treated the crowd and the game with massive disdain, as if the whole affair was far beneath his dignity. He showed only one speck of interest in the proceedings, but it was decisive. He was about 30 yards from the Barnsley goal and with his back to it, when he received a fast, wild cross. He killed it in mid-air with his right foot and hit an alarming left-foot volley into the roof of the Barnsley goal. Carter didn't wait to see where the ball had gone. He knew. He continued to spin through 180 degrees and strolled back to the halfway line as if nothing had happened. Normally the Barnsley crowd greeted any goal by the opposition with a loud silence, but as Carter reached the halfway line a rare thing happened: someone shouted, "I wish we'd get 11 like thee, Carter lad." The great player allowed himself a thin smile, as well he might, for he never received a greater accolade than that.

(16) Arthur Appleton, Hotbed of Soccer (1960)

In 1960, Arthur Appleton in his book Hotbed of Soccer wrote that, "before the War Sunderland fans had, in the main, been slow to value Carter at his true worth, partly because he had developed with other excellent players ... although he was a local boy he was not generally taken to heart mainly, I think, because of his impassive demeanour. His efficiency as a footballer, although recognised by quite a few, was not fully appreciated until he had left - and really emerged as a national figure - during and immediately after the War. Carter was Sunderland's most consistently effective inside forward since Buchan.