Charlie Buchan

Charles (Charlie) Buchan was born in Plumstead on 22nd September 1891. His father, who originally came from Aberdeen, was a sergeant in the Highland regiment but had moved to London to become a blacksmith.

Buchan took a keen interest in football and was a fan of local side, Woolwich Arsenal. He watched the players train but could not afford to pay the entrance fee to see games. Buchan points out in his autobiography, A Lifetime in Football: "As my pocket-money was the princely sum of 1d, I could not pay the 3d admission into the ground. I waited outside, listening to the roars and cheers of the crowd, until about ten minutes before the end when the big, wide gates were thrown open to allow the crowd to trek out."

His favourite players at the time were Jimmy Ashcroft, Bobby Templeton, Tim Coleman, Percy Sands, Jimmy Sharp, Charlie Satterthwaite and Roderick McEachrane. As Buchan later pointed out: "They were the stars upon whom I tried to model my style."

When he was aged 17 years old Buchan was approached by Arsenal and asked to play for the reserves against Croydon Common. Arsenal won 3-1 and Buchan scored one of the goals. Buchan played in three more games and trained twice a week with the team. However, when he provided a bill of 11 shillings for his travel costs, the club refused to reimburse him. As a result, Buchan refused to play anymore games for the club.

For the rest of the 1909-10 season Buchan played for Northfleet in the Kent League. Football scouts soon became aware of Buchan's abilities and the First Division side Bury offered him wages of £3 a week. Sir Henry Norris, the chairman of Fulham, told Buchan: "We understand you want to be a teacher. we will find you a job where you can continue your training and pay you thirty shillings a week to sign professional forms for Fulham." Buchan asked for £2 a week but this was rejected.

Buchan eventually accepted an offer from Leyton, a club that played in the Southern League. He was paid £3 a week and allowed to continue his studies in order to qualify as a teacher. His first game was against Plymouth Argyle in September 1910. A great influence on Buchan was Kenneth Hunt, who had previously played for Oxford University and Wolverhampton Wanderers.

Buchan had a good first season and soon the big clubs were trying to buy him. Leyton turned down an offer of £800 from Chelsea. However, in March 1911, Sunderland paid a transfer fee of £1,200 for Buchan. This beat the £1,000 paid by Middlesbrough for Alf Common in 1905.

In his autobiography, A Lifetime in Football, Buchan recalls how defenders tried to intimidate him in those early Football League games. In his third game for the club, against Notts County, Buchan faced Jack Montgomery, a burly left-back. In the first few minutes of the game, Buchan raced past him before passing to a teammate. Montgomery, warned him in a low voice: "Don't do that again, son." When Buchan tried the same trick later, Montgomery hit him with a shoulder charge of such force that he finished up flat on his back only a yard from the fencing surrounding the pitch. As he crept back on to the field, Montgomery went over to Buchan and said: "I told you not to do it again."

The Sunderland fans did not immediately take to Buchan and he suffered a great deal of barracking from the Roker Park crowd. Buchan asked to be dropped from the side but Bob Kyle, the manager, refused. After one game in November, 1911, Buchan told Kyle: "I'll never kick another ball for Sunderland."

Kyle persuaded Buchan to play one more game for the club. He agreed and scored two goals in the 3-1 victory. Buchan recalled that this was the turning point and never again got "the bird" from the crowd.

Buchan gradually developed a very good partnership with George Holley, Sunderland's leading goalscorer. Buchan later argued that in a game against Bradford City, Holley performance was the best he ever saw by an inside-forward. "He scored a magnificent hat-trick, running nearly half the length of the field each time and coolly dribbling the ball round goalkeeper Jock Ewart before placing it in the net."

George Holley also supplied Buchan with the passes for a large percentage of the goals he scored for Sunderland. In one game he scored five goals against Kenneth Campbell, the Scottish international goalkeeper, who at the time played for Liverpool. "Four of them I just touched into the net. Holley had beaten the defence and even drawn Campbell out of position before giving me the goals on a plate."

At the beginning of the 1912-13 season Bob Kyle paid £3,000 for two defenders, Charlie Gladwin and Joe Butler. This was a large sum of money. At the time, the record transfer fee was the £1,800 paid by Blackburn Rovers to West Ham United for prolific goalscorer Danny Shea.

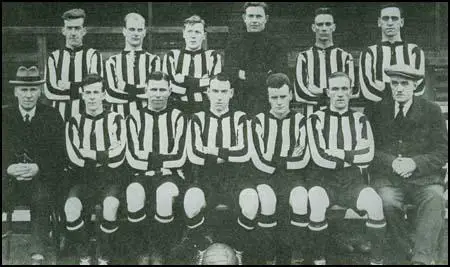

Kyle also purchased James Richardson from Huddersfield Town to play alongside Buchan, George Holley, Henry Martin and Jackie Mordue, in the forward line. The defence was made up of Joe Butler in goal, Charlie Gladwin and Albert Milton, full backs, with Frank Cuggy, Charlie Thomson and Harry Low playing in the half-back line.

The season started badly and by mid-October Sunderland was bottom of the First Division table with only two points in seven games. However, the new players gradually integrated into the side and the club moved up the table by winning the next five games. By the end of December 1912 Sunderland was challenging for the title with Buchan, George Holley and Jackie Mordue, all having scored 12 goals each. However, according to Buchan it was a defender, Charlie Gladwin, that was the real reason why Sunderland played so well. "He stabilized the defence and gave the wing half-backs Frank Cuggy and Harry Low the confidence to go upfield and join in attacking movements. Sunderland became a first-class team from the moment he joined the side."

January 1913 saw Sunderland beat Arsenal (4-1), Tottenham Hotspur (2-1), Chelsea (4-0), Middlesbrough (2-0) and Derby County (3-0). It was now clear that only Aston Villa could deprive Sunderland of the First Division championship.

Sunderland also had a good FA Cup run. On the way to the final Sunderland beat Manchester City (2-0), Swindon Town (4-2), Newcastle United (3-0) and Burnley (3-2). The final was played in front of 120,000 at Crystal Palace against Aston Villa, their rivals for the league championship. Early in the game, Clem Stephenson told Buchan that the previous night he had dreamt that Villa won the game 1-0 with Tommy Barber scoring the only goal with a header.

The game included a running battle between Charlie Thomson, the Sunderland centre-half and Harry Hampton, Aston Villa's tough centre-forward. Hampton had a reputation for being rough on goalkeepers. One local commentator reported that: "Thomson was the centre of one of the main talking points of the game after a thrilling duel with the Villa forward Hampton. He had scored for England against Thomson's Scotland by charging the keeper over the line. Charlie was determined this was not going to happen during the Cup Final, so early on he laid Hampton out to let him know who was boss!"

Thomson decided to protect his goalkeeper, Joe Butler, by making a heavy challenge on Hampton early on the game. A journalist reported: "Thomson had great difficulty in holding the nippy Villa inside forwards and fouled Hampton so badly that the centre forward was prostrate for several minutes. Later in the game Hampton viciously retaliated by kicking Thomson when he was on the ground and it was regrettable that the game was marred by such unseemly incidents."

In his autobiography, A Lifetime in Football, Buchan recorded: "Thomson and Hampton soon got at loggerheads and rather overstepped the mark in one particular episode. Though neither was sent off the field, they each received a month's suspension." The referee, Albert Adams, was also banned for a month for failing to maintain order. Adams was never asked again to officiate in another professional football game.

Just before the end of the first-half, Clem Stephenson was brought down in the 18-yard box by Charlie Gladwin. However, Charlie Wallace, dragged his penalty shot wide of the post.

Soon after the interval Harry Hampton had a goal disallowed for offside. This was followed by Sam Hardy, the Aston Villa goalkeeper being injured after a clash with Henry Martin and for a time Sunderland played against ten men. Although they hit the upright twice and had one shot cleared off the line, they could not score against Jim Harrop, the Villa centre-half, who had replaced Hardy as goalkeeper.

With 15 minutes remaining Charlie Wallace took a corner-kick. He scuffed the ball and it came into the box at waist height. With the Sunderland defence expecting a high-ball, Tommy Barber was able to ghost in from midfield and head it into the net. Stephenson's dream had come true.

Four days later Sunderland played Aston Villa in the league. Sunderland was only two points in front of their rivals with only three games to go, they had to avoid defeat in order to make sure they won the First Division championship. Over 70,000 watched Harold Halse score the opening goal. However, Sunderland fought back and Walter Tinsley converted a pass from Henry Martin to earn a 1-1 draw.

Sunderland won their last two matches against Bolton Wanderers (4-1) and Bradford City (1-0) to win the title by four points from Aston Villa. Charlie Buchan finished as the club's top scorer with an impressive 32 goals in 46 games.

Buchan won his first international cap for England against Ireland on 15th February, 1913. The England team that day also included Bob Crompton, Frank Cuggy, George Elliott, Jackie Mordue, Joe Smith and George Wall. Buchan scored in the 10th minute but Ireland eventually won the game 2-1. After the game Buchan got involved in a argument with a member of the F.A. Selection committee. As a result he was dropped from the team.

On the outbreak of the First World War Buchan joined the Grenadier Guards. In 1916 he was sent to the Western Front and saw action at the Somme, Cambrai and Passchendaele. Buchan was quickly promoted to the rank of sergeant and in 1918 he attended the Officers' Cadet School at Catterick.

After the war Buchan returned to his teaching job at Cowan Terrace School in Sunderland. However, in his autobiography, A Lifetime in Football, Buchan admitted that he was finding that "teaching and playing professional did not mix... by the time Friday came round I could hardly talk to the class... I could not concentrate on both at the same time." At the end of the 1919-20 season he gave up teaching and opened a sports outfitters business in Blandford Street, near the south end of Sunderland Railway Station.

Buchan won his second international cap for England on 15th March, 1920. The England team against Wales that day also included Sam Hardy, George Elliott, Frank Barson and Joe Smith. Buchan scored in the 7th minute but Wales eventually won the game 2-1.

Buchan was a member of the committee that ran Association Footballers' Union (AFU). After the war professional footballers received a maximum weekly wage of £10. In 1920 the Football League Management Committee proposed a reduction to £9 per week maximum. Buchan was one of those who called for the AFU to resort to strike action. However, large numbers of players resigned from the union and the Football League was able to impose the £9 maximum wage. The following year it was reduced to £8 for a 37 weeks playing season and £6 for the 15 weeks close season.

Sunderland failed to recapture its pre-war form. By the time the Football League resumed, several of its best players were past their best. In both the 1920-21 and 1921-22 seasons the club finished in 12th place.

Bob Kyle completely rebuilt the playing squad and by the 1922-23 season Buchan was the only survivor of the Sunderland team that won the Football League title in the 1912-13 season. Sunderland had a much better season and finished in second place, six points behind Liverpool. Buchan scored 30 goals that made him the top scorer in the whole of the First Division.

Buchan played his last international game for England on 12th April 1924. The game against Scotland ended in a 1-1 draw. He had managed to score four goals in six games but the First World War and his conflict with those in authority severely restricted his international appearances.

In May 1925 Herbert Chapman visited Charlie Buchan in his sports outfitters shop. He asked him if he was willing to be transferred to Arsenal. Buchan, who had scored 209 goals in 380 games for Sunderland, agreed and after two months of negotiations, he joined the London club. Bob Kyle explained to Buchan the complex arrangements of the deal: "We pay Sunderland cash down £2,000, and then we hand over £100 to them for every goal you score during your first season with Arsenal."

At that time most teams played in the 2-3-5 formation. This system dominated football until 1925 when the Football Association decided to change the offside rule. The change reduced the number of opposition players that an attacker needed between himself and the goal-line from three to two.

Charlie Buchan suggested to Herbert Chapman, that the team should exploit this change in the law to create a new playing formation. At that time the centre-half played a much more attacking role. Buchan argued that the club should now have a more defence-minded player in that position and that he, rather than the two full-backs, should take responsibility for the offside trap. The full-backs played just in front of the centre-half whereas one of the inside-forwards should act as a link between attack and defence. The formation was therefore changed from 2-3-5 to 3-3-4. This also became known as the "WM" formation.

Herbert Roberts was selected to play the centre-half role and the veteran Andy Neil was the link man in the system. Later, Alex James successfully took over Neil's role.

That season Arsenal finished in second-place to Chapman's old club, Huddersfield Town. Buchan scored 21 goals that season which brought the amount paid by Arsenal to Sunderland to £4,100.

Henry Norris refused to allow Herbert Chapman to spend too much money to strengthen his team and in the 1926-27 season Arsenal finished in 11th position. However, they did enjoy a good run in the FA Cup. They beat Port Vale (0-1), Liverpool (2-0), Wolverhampton Wanderers (1-0) and Southampton (2-1) to reach the final at Wembley against Cardiff City.

With 17 minutes to go, Hughie Ferguson hit a shot at the Arsenal goal that was partly blocked by Tom Parker. As the goalkeeper, Dan Lewis, later explained: "I got down to it and stopped it. I can usually pick up a ball with one hand, but as I was laying over the ball. I had to use both hands to pick it up, and already a Cardiff forward was rushing down on me. The ball was very greasy. When it touched Parker it had evidently acquired a tremendous spin, and for a second it must have been spinning beneath me. At my first touch it shot away over my arm."

Ernie Curtis, Cardiff's left-winger, later commented: "I was in line with the edge of the penalty area on the right when Hughie Ferguson hit the shot which Arsenal's goalie had crouched down for a little early. The ball spun as it travelled towards him, having taken a slight deflection so he was now slightly out of line with it. Len Davies was following the shot in and I think Dan must have had one eye on him. The result was that he didn't take it cleanly and it squirmed under him and over the line. Len jumped over him and into the net, but never actually touched it."

In the words of Charlie Buchan: "He (Lewis) gathered the ball in his arms. As he rose, his knee hit the ball and sent it out of his grasp. In trying to retrieve it, Lewis only knocked it further towards the goal. The ball, with Len Davies following up, trickled slowly but inexorably over the goal-line with hardly enough strength to reach the net."

Soon afterwards, Arsenal had a great chance to draw level. As Charlie Buchan later explained: "Outside-left Sid Hoar sent across a long, high centre. Tom Farquharson, Cardiff goalkeeper, rushed out to meet the danger. The ball dropped just beside the penalty spot and bounced high above his outstretched fingers. Jimmy Brain and I rushed forward together to head the ball into the empty goal. At the last moment Jimmy left it to me. I unfortunately left it to him. Between us, we missed the golden opportunity of the game." Arsenal had no more chances after that and therefore Cardiff City won the game 1-0.

After the game Dan Lewis was so upset that his mistake had cost Arsenal the FA Cup that he threw away his loser's medal. It was retrieved by Bob John who suggested that the team would win him a winning medal the following season. Herbert Chapman believed that Lewis was the best goalkeeper at the club and he retained his place in the team the following season.

Arsenal had no more chances after that and therefore Cardiff City won the game 1-0. Buchan was bitterly disappointed as he was now approaching his 36th birthday and he knew it was his last chance to win a cup-winners medal. Buchan, who had scored 49 goals in 102 games for Arsenal decided to retire from playing professional football at the end of the season.

Buchan was offered a job writing about football for the Daily Chronicle. He also made radio broadcasts for the BBC. In 1947 he helped establish the Football Writers' Association (FWA). One of the FWA's first decisions was to introduce an annual Footballer of the Year Award, decided by a vote amongst FWW members. The first winner, in 1948, was Stanley Matthews.

In September 1951 he launched the highly successful Charles Buchan's Football Monthly. He published his autobiography, A Lifetime in Football in 1955.

Charlie Buchan died on 25th June 1960 while on holiday in Monte Carlo.

Primary Sources

(1) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

Always I carried some sort of a ball in my pocket. It did not stay there long. I used to run along the road, using the pavement edge as a colleague.

I fear that in these days of heavy traffic, it would be impossible to carry out this sort of practice. But I thought nothing of it. I became so adept at pushing the ball against the pavement and taking the rebound that it did not impede my rate of progress.

When I first played for the Polytechnic, my position was left half-back. In one game I happened to score five goals. So I was immediately put into the forward line where I remained for the rest of my playing days.

Then I had ambitions of becoming a centre-half, but I was too small for the position. Though I was big enough in after years, nobody seemed to fancy me as a pivot. At any rate, I never played in the position.

Playing regularly for the school team was not enough to satisfy my appetite for the game. Every Saturday afternoon I went down to the Manor Field to see what I could of Arsenal's League and reserve sides.

As my weekly pocket-money was the princely sum of id, I could not pay the 3d admission into the ground. I waited outside, listening to the roars and cheers of the crowd, until about ten minutes before the end when the big, wide gates were thrown open to allow the crowd to trek out.

In I rushed with other soccer-crazy boys to see the finish of the game. It was enough to get a glimpse of my heroes and to watch the way they played the game.

Among my favourites then were Bobby Templeton, Scottish international wing forward; big, burly Charlie Satterthwaite, an inside-left with a cannon-ball shot; Tim Coleman, a born humorist and inside-right whom, eventually, I succeeded at Sunderland; Percy Sands, the local schoolmaster centre-half; Roddy McEachrane, a consistently good left half-back and Jimmy Sharp, the youthful looking full-back.

They were the stars upon whom I tried to model my style. And there was no greater pleasure for me than to go, during the training month of August, and in the school holidays, to watch them kicking-in and sometimes retrieve the ball when it went behind the goal.

(2) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

During the summer months, I stayed at work. Then I received notice to report for training at Osborne Road the day after August Bank Holiday. In those days, the season opened on the first Saturday in September, so the whole of August could be devoted to strenuous training. It also ended on the last Saturday in April.

Since then the season has been extended and takes in the last week in August and the first week in May. I think this is one of the mistakes made by the ruling bodies. League football in cricket weather and on bone-hard grounds is neither good for the player nor for the standard of play. It takes too much out of the player, physically and mentally.

That August, in 1910, was my first experience of systematic training. We trained twice each day and trained hard. Much harder than when I came back to London fifteen years later. Then, after the opening month, I went to the ground only once daily.

Though present-day players may have modern appliances to assist them, I still believe the old-timer was physically fitter. Or I should rather say they were a tougher breed of men.

(3) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

I was chosen as inside-right for the first home game, against Plymouth Argyle at Osborne Road. But I had another disturbing shock before I was allowed to kick a ball.

When I walked into the dressing-room, about an hour before he kick-off, George Ryder, our inside-left and father of Terry Ryder, now a professional, came up to me and said: "We're waiting for word that the players are to go on strike. Will you join with the rest of the boys?"

Though I had not then joined the Players' Union, which was discussing the problem, I replied: "Yes, I'll do exactly as the others. In fact, I have no choice, if the rest aren't going to turn out."

We spent anxious minutes waiting, before the word came through that the strike was off. It had been settled in Manchester where those great players, Charlie Roberts and Billy Meredith who became great friends of mine later on-bore the brunt of the proceedings. I joined the Union the next week.

(4) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

During the course of my apprenticeship with Leyton, I had another stroke of luck. About two months after the season started, the Rev K. R. G. Hunt joined the club and played regularly behind me at right half-back.

Only two years previously, he had been right-half for Wolverhampton Wanderers when they unexpectedly defeated Newcastle United in the F.A. Cup final at Crystal Palace. The big, strong cleric was noted for his vigorous charging. He delighted in an honest shoulder charge, delivered with all the might of his powerful frame. He was an opponent, not to be feared-as he never did an unfair thing in his life-but to be avoided if possible.

Years afterwards I spoke to Billy Meredith, the great Welsh international outside-right, who played fifty-one times for his country. The name of Hunt cropped up. Meredith said: "I never ran up against a harder or fitter half-back. It was like running up against a brick wall when he charged you."

"But," I replied, "he was also a great player. He helped me a lot when I played in front of him."

"Oh, yes, his positioning was perfect. He seldom allowed you a yard of room in which to work. I'm glad I didn't have to meet him very often."

It was Hunt who instilled in me the art of positioning. In his quiet voice he would tell me where to go when he had the ball, or where to position myself when we were on the defensive. They are two of the most important assets of an inside-forward, who should be a link between attack and defence.

(5) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

Throughout the week-end, they visited the Leyton ground and my home at Woolwich. I told them all to interview my father who put some of them off with the news that I would not leave home. The size of the transfer fee asked by Leyton put others off.

Then, on the Tuesday, I went to the Leyton ground. Manager Dave Buchanan told me I was wanted in the office. Bob Kyle, Sunderland manager, was waiting there.

When I went in, he said: "How would you like to play for Sunderland in the First Division? You'll get maximum wages and a ten pounds signing-on fee."

To be perfectly frank I did not know exactly where Sunderland was. I knew it was on the north-east coast somewhere near Newcastle, but that was all. It seemed very far away from home.

After talking the matter over, Kyle said: "You know, you'll never get a better chance. I can promise you a place in the first team for the rest of this season at least."

That settled the argument. I signed, received the £10 fee, and went in the dressing-room to prepare for training. When Dave Buchanan heard I had signed he was the most disappointed man I met. He wanted me to go to Everton.

The Sunderland manager came into the dressing-room a minute or two afterwards and said: "Son, it's very cold up north, so I advise you to get an outfit of thick winter clothes. You'll need them."

I did. I bought a new, lined overcoat (£4 4s) a tweed suit (£2 10s), in fact, a completely new outfit of what I thought would keep me warm in any climate. And the whole lot did not amount to the £10 signing fee. Today they would cost nearer £100. But within six months, they were no use to me whatever. I had grown right out of them.

(6) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

During my second home game for Sunderland I got another of those valuable lessons that were offered gratuitously by the great players in those days.

It was in the early stages of the game with Notts County. The left-back opposed to me was a broad-shouldered, thick-set fellow called Montgomery, only about 5ft. 5 in. in height but as tough as the most solid British oak.

The first time I got the ball, I slipped it past him on the outside, darted round him on the inside and finished with a pass to my partner.

It was a trick I had seen Jackie Mordue bring off. It worked wonderfully well. But as I came back down the field, Montgomery said in a low voice: "Don't do that again, son."

Of course I took no notice. The next time I got the ball, I pushed it past him on the outside but that was as far as I got. He hit me with the full force of his burly frame so hard that I finished up flat on my back only a yard from the fencing surrounding the pitch.

It was a perfectly fair shoulder charge that shook every bone in my body. As I slowly crept back on to the field, Montgomery came up and said: "I told you not to do it again."

I never did afterwards. I learned my lesson the painful way and never tried to beat an opponent twice running with the same trick. It made me think up new ways; a very valuable lesson.

(7) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

The crowd began to barrack me and I must admit I deserved it. I asked to be dropped from the side but the manager would not listen.

Finally after one game in mid-November when the crowd had, with every reason, been noisily expressive about my play, I stormed into the dressing-room and declared in a loud voice: "I'll never kick another ball for Sunderland."

Unfortunately, the local reporter heard me. In the evening paper, there were bold headlines on my statement. On Monday morning there were more reports.

Though I received hundreds of letters urging me to carry on, I packed up my bag and went home to Woolwich.

On the following Saturday, Sunderland were to play Woolwich Arsenal at the Manor Field, which was only about half-a mile from my home. I did not expect to play.

But two days before the game, Manager Kyle came to the house and, after a talk with my father, persuaded me to turn out. "Do your best to show the locals you can do it," he said, "and if you fail, we can talk about it afterwards."

I played, scored a couple of goals in a 3-I win for Sunderland, and felt much better afterwards. I stayed the following week at home and somehow felt a lot stronger.

That was the turning point. I returned to Sunderland and began to put on weight. I quickly ran up to 12st. 8lb. - my playing weight for the rest of my days - and struck a little form.

No longer did I get "the bird" from the crowd. They were very kind to me, as they were for the fourteen and a half years I spent with the club.

During this testing time I owed a debt of gratitude to trainer Billy Williams that I never repaid nor ever could repay. He looked after me like a father. If I got the slightest knock he came round to my house to attend to it at once. He also nursed me during training hours, saw that I did not overtax my strength and gave me tonics when he thought them necessary. At the time it was very often.

After I had been a few weeks at Sunderland, he noticed that I smoked quite a number of cigarettes during the day. Cigarettes were his pet aversion.

One day he handed me a new pipe, a pouch full of tobacco and a box of matches. "I want you to promise me that you will give this a fair trial and leave cigarettes alone," he said.

Taken by surprise, I gave him my promise. I smoked nothing but a pipe from that day until just over three years ago when I parted company with my teeth.

Trainer Williams was a strict disciplinarian. One day I arrived a minute or two after the time we were due to report for duty. There he stood at the door waiting for me to enter. Without a word, he pulled his watch from his pocket, looked at it then put it back. I felt very guilty. A few seconds later, he pulled out his watch again and repeated the performance. It made me feel so small that I vowed I would never be late for training again. I kept my vow.

While we were in the dressing-rooms during training hours or on match days, smoking was strictly forbidden. If a club director came into the room smoking, he was quickly ordered out. Williams was king of his own castle.

(8) John Hudson, Sunderland: The Official History (1999)

The date was 7th December, 1912, the score 7-0...For Charlie Buchan it was a personal triumph. Strangely, the man of the match was Liverpool's goalkeeper Campbell, who was outstanding; but for him it would have been double figures for Sunderland. There were clear opportunities early on for both sides, but it was Sunderland who took the lead. From a quick break Hall ran away, laid off the ball to Buchan, who with a swift low shot opened the scoring... Buchan coolly slotting home a cross from Martin. After the interval the Lads were straight on the attack looking for more goals. Nevertheless, it took until 21 minutes after break for the fifth goal, Buchan once again the man, registering his hat trick after converting a left-wing cross. Five minutes later and Buchan was beginning to make it a one-man show. Mordue took a corner, flighting it in beautifully, and after Campbell parried a shot, Buchan lashed the loose ball into the back of the net for the sixth. Having totally outclassed the opposition, we now took it easy, but with only four minutes left Holley strolled down the wing and crossed to Buchan who put in his fifth goal, and Sunderland's seventh.

(9) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

Bob Kyle went into the transfer market. He bought Charlie Gladwin, six-foot-one-inch, fourteen stone Blackpool right-back, and Joe Butler, Stockport County goalkeeper.

Local people thought he must have gone crazy to pay something like £3,000 for the two. In those days, when the record transfer fee was £1,850, paid by Blackburn Rovers to West Ham United for inside-right Danny Shea, it was a lot of money, worth, I should say, ten times the amount today.

It was money well spent. From the moment Gladwin and Butler joined the side, Sunderland went ahead and became the finest team I ever played for, and one of the best I have ever seen.

Not only did we win the League Championship with a record number of points, but we nearly brought off the elusive League and Cup double, accomplished only by Preston North End and Aston Villa.

We reached the F.A. Cup final, only to be beaten by Aston Villa at the Crystal Palace before a record crowd.

Joe Butler, short and sturdy, very like Bill Shortt, the Plymouth Argyle and Welsh international goalkeeper, was reliable rather than spectacular, but it was Gladwin who revitalized the side.

There are people who say that no one player can make a poor side into a great one, and that there isn't one worth a £3,000 transfer fee. Gladwin proved they are wrong.

He used his tremendous physique to the fullest advantage. Before a game he would say: "When there's a corner-kick against us, all clear out of the penalty-area. Leave it to me."

We invariably did. But one day Charlie Thomson, our captain and centre-half with the big, black, flowing moustache, forgot the instruction.

The ball came across the goal ... Gladwin, as usual, got it and his mighty clearance struck Thomson full in the face. He went down like a log.

That was just before half-time. Thomson was brought round in time to take his place after the interval, but when he came out he joined the other side and started to play against us. He was suffering from concussion.

Gladwin was one of those full-backs who never read a newspaper or knew whom he was playing against. He was a natural player who went for the ball-and usually got it. Before a game, a colleague would say to him: "You're up against Jocky Simpson today so you're for it." All Gladwin would say was: "Who's Jocky Simpson?" At that time, Simpson was as well-known and as famous as Stanley Matthews is today.

At other times, one would say to Gladwin: "You must be on your best behaviour, Tityrus is reporting the game."

Now Tityrus, the mighty atom Jimmy Catton, was the out standing sports writer of his day and editor of the Athletic News, known then as the "Footballers' Bible".

Yet Gladwin's only remark was: "Who's Tityrus"?

Before every game, Gladwin pushed his finger down his throat and made himself sick. It was his way of conquering his nerves. Yet on the field he was one of the most uncompromising and fearless players I have known.

He stabilized the defence and gave the wing half-backs Frank Cuggy and Harry Low the confidence to go upfield and join in attacking movements.

Sunderland became a first-class team from the moment he joined the side. He was worth his weight in gold; yes, more than the £34,500 paid for Jackie Sewell.

With Gladwin and Butler consolidating the defence, Sunderland gradually crept up the League table until we knew we had a chance of winning the championship-there was only one team we feared, Aston Villa.

(10) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

A week before the final we got a shock - George Holley, our great inside-left, received a severe ankle injury which threatened to keep him out of the game. After a test on the morning of the final, it was decided to play him.

It proved to be the most sensational of all the Crystal Palace finals. It was crowded with incidents, some of which are better forgotten.

First, there was the trouble between Charlie Thomson, our centre-half and Harry Hampton, Villa's dynamic centre-forward, the terror of goalkeepers. It was Hampton, who, in 1913, won an international for England at Stamford Bridge by charging Brownlie, the Scottish goalkeeper, with the ball in his arms, into the net.

Thomson and Hampton soon got at loggerheads and rather overstepped the mark in one particular episode. Though neither was sent off the field, they each received a month's suspension; the first month of the following season.

There was also an injury to Villa goalkeeper, Sam Hardy, which kept him off the field for about twenty minutes. The game was held up for seven minutes, making it the longest final, apart from extra-time, in the history of the event.

Hardy, I consider the finest goalkeeper I played against. By uncanny anticipation and wonderful positional sense he seemed to act like a magnet to the ball.

I never saw him dive full length to make a save. He advanced a yard or two and so narrowed the shooting angle that forwards usually sent the ball straight at him.

When the game was resumed, with Villa centre-half Jim Harrop in goal, we peppered away at the Villa goal. We hit the upright twice, but simply could not get the bail into the net.

Then, midway in this half, with Hardy back in goal, Villa forced a corner-kick on the right. Charlie Wallace took it and sent the ball waist-high somewhere about the penalty-line, a bad kick really.

Tom Barber, Villa right-half, dashed forward and got his head to the ball. As our defenders stood apparently spellbound the ball passed slowly between them into the corner of the net.

This amazing goal was enough to give Villa the Cup and made a dream come true for Clem Stephenson, Villa inside-left, of the stocky frame and north-country accent.

When we were lined up for a throw-in soon after the game started, Clem said to me: "Charlie, we're going to beat you by a goal to nothing."

"Oh," I replied, "what makes you think that?"

"I dreamed it last night," said Clem "also that Tom Barber's going to score the winning goal." I could not help but think of a song at the time which had these words: "Dreams very often come true."

A great schemer and tactician, Clem brought the best out of his colleagues by his accurate, well-timed passes. He was by no means fast but made the ball do the work.

He was the general who led the brilliant Huddersfield team to three successive League championships.

(11) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

Out in France I could never escape from football. I did not want to. Rather I was glad of an opportunity to play. My first game was behind the Somme front, just after the big push in July 1916, at our camp in Marie-court, a little north of Albert.

From the playing field we could see the spire of Arras church.

Legend had it that when the statue of the Virgin Mary, hanging at right angles, fell, the war would end. We devoutly wished it would fall right then.

No sooner had we started than German shells began to drop perilously near the field. So we packed up and restarted on another pitch. The game had to go on.

We fielded a Grenadier Guards team and I had the job of getting the side together-I had been promoted to sergeant by this time.

One of our officers was the outside-left. When I went to his tent to tell him about the game, he was not there, so I spoke to his batman. He was our goalkeeper, Harry Jefferies, who played for Queen's Park Rangers and Bristol City.

I persuaded Harry to let me have one of the officer's shirts. Mine were in such a verminous state it was impossible to wear them.

Just as I got the shirt, I saw, through the flap of the tent, the officer approaching. Hastily I tucked the shirt up the back of my tunic. I gave the officer the message and as I was going out he said:

"Oh, Sergeant, you might tuck your shirt in, it looks unsightly." The arm of the shirt was hanging down like a tail.

Our keen rivals were the Scots Guards. In their ranks were Sammy Chedgzoy and Billy Kirsopp who, before the war, had been Everton's right-wing in many League games. It was strange that later I partnered Chedgzoy in inter-League games against the Scottish League.

Well, I got through the Somme, Cambrai and Passchendaele battles without a scratch. Then I came home and was posted to an Officers' Cadet School, at Catterick Camp, for three months training.

(12) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

At the end of the first post-war season - 1919-20 - trouble broke out concerning players' wages. I was on the Players' Union Committee at the time and we wanted the weekly wage stabilized at £10 per week maximum.

The League Management Committee, the mouthpiece of the clubs, proposed a reduction to £9 per week maximum. The Union held a delegates' meeting in Manchester at which it was unanimously decided to call a strike.

The delegates were instructed to go back to their teams and vote "yes or no" on strike action and come back to another meeting on the following Monday.

In the meantime, however, several teams re-signed en bloc. So there could be no strike. The upshot was they had to accept the League's terms £9 per week maximum.

Worse followed at the end of the following season, 1920-1, when the wages were reduced to a maximum of £8 for a 37 weeks playing season and £6 for the 15 weeks close season.

All the time, the Union were pressing for the abolition of wage restrictions. They called for a "no limit" wage but the clubs would have none of it.

If the players had pressed their claims in the summer of 1920, I am sure they would have got their terms. As it was, they failed to get together as a body and were overruled.

Much the same is going on today. The Union are pressing for the abolition of the maximum wage and new contracts for players. They will never get them unless they work together in closer harmony.

(13) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

One day in May 1925, I was serving in my Sunderland shop, when the great Herbert Chapman walked in. A few weeks before, he had left Huddersfield Town to take over the managership of Arsenal.

His first words on seeing me were: "I have come to sign you on for Arsenal."

"Yes,' I replied, thinking he was joking, "shall we go into the back room and sign the forms?"

"I'm serious," was his answer. "I want you to come with me to Highbury."

"Have you spoken to Sunderland about it?" I asked, still thinking it was all part of the joke.

"Oh, yes," said Mr Chapman. "If you don't believe me, ring up Bob Kyle, and he'll tell you."

Still unbelieving, I phoned the Sunderland manager. "Yes," he said, "we have given Arsenal permission to approach you."

"Do you want me to go?" I asked him.

"We are leaving that to you," he said. "Do what you think best for yourself. It's in your hands."

Slowly I put down the receiver. I was almost stunned by what I had heard. It had never crossed my mind that Sunderland would be prepared to part with me so easily.

Mr Chapman just said one word: "Well?"

And all I could say at that moment was: "Give me time to think it over. Come back tomorrow, and I will let you know, one way or the other."

When I went home that evening I talked the matter over with the family. The thing that hurt most was that, after more than fourteen years with Sunderland, my services were so lightly regarded.

Finally I made up my mind. The next morning Mr Chapman again called at the shop. I said to him: "I am prepared to sign for Arsenal, but I shan't do so until the end of July."

"Will you give me your word you'll sign then?" he asked; and when I replied "Yes", we talked of other things. A lot of them concerned the Arsenal team and what I thought about them.

A few weeks later, a Sunderland director, Mr George Short, called on me at the shop. "What's this about your leaving Sunderland?" he asked. When I told him, he replied: "Then I shall resign."

He kept his word. It seemed there were sharply divided opinions about my leaving, but the strange thing is that nobody asked me to change my mind.

The summer went by, and then towards the end of July, Mr Chapman again visited me in Sunderland to complete the negotiations.

It was arranged that I should go to London to talk with the Arsenal chairman, Sir Henry Norris, and a director, Mr William Hall. At the same time I was to look over houses similar to the one I had in Sunderland.

As soon as the housing accommodation was settled - and that was not the difficult matter it is today - I met Mr Chapman again to sign the necessary forms.

Before doing so I asked him, as a matter of personal satisfaction, what was the transfer fee.

After a little persuasion he gave me an answer. It was almost as big a shock as the transfer itself.

He said: "Well, it's rather a peculiar one. We pay Sunderland cash down £2,000, and then we hand over £100 to them for every goal you score during your first season with Arsenal."

(14) (14)Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

Within a few days of my arrival at Highbury, Mr Chapman called a meeting of the players. I was appointed captain. Though I did not want the job - I thought I would be of greater service as one of the rank and file-they insisted I should be in charge on the field.

One of the first things we did was to create a spirit of friendship among the whole staff. All were to be pals, working for the good of the club.

We discussed matters from all sides, ironing out any bones of contention. We soon became hundred per cent Arsenal players.

That, I think, is the secret of the team's unrivalled success over the years. The club comes first. Team-work is not allowed to suffer from petty squabbling.

Weekly meetings were instituted. On the eve of every match, big or small, the players, manager and trainer, talked it over.

We had no blackboards or plans of the field. It was a straightforward discussion, with every player airing his point of view. We talked over moves for every basic part of the game, such as throws-in, corner-kicks, free-kicks, and the strong and weak points of our own team, as well as the opposition.

We soon knew what every player was expected to do.

It was an accepted principle that we never discussed any move that the opposition could interfere with. We concentrated on our own side-covering, backing up, calling for the ball, and any point that we could work out for ourselves.

Every player was made to talk. Some took a lot of persuading, but eventually all joined in, even the most self-conscious and the "silent ones".

It was during the summer of 1925 that the change in the offside law was made. It was the biggest upheaval in the game for many years, and, in my opinion, altered it completely.

It was necessary, though. There were so many full-backs copying the example of Bill McCracken, Newcastle and Irish international full-back, known as the "offside king", that the game was fast developing into a procession of free-kicks for offside.

The change from three defenders to two between an attacker and the goal brought about a revision of tactics from the old spectacular passing movements and brilliant individualism, to the thrilling "three-kick" raids on goal and team-work; from frills to thrills.

Many people will say it was a change for the worse. But after all, it is what the public wants nowadays. They pay the piper so they should call the tune.

The change certainly brought the end of the old style. New methods were required and Arsenal were the first to exploit them...

Mr Chapman called upon me to outline the scheme I had in mind. I said I not only wanted a defensive centre-half but also a roving inside-forward, like a fly-half in rugby, to act as link between attack and defence.

He was to take up such positions in mid-field that any defender would be able to give him the ball without the chance of an opponent intercepting it. Of course, I had in mind that I would be the forward proposed for this job.

First we thrashed out the position of the centre-half. He was not to be a "policeman" to the opposing centre-forward. He was given a beat of a certain area bordering the penalty-line which he was to guard. The other defenders were to range themselves around him according to the direction of play.

It was the beginning of Arsenal's "defence in depth" policy, brought almost to perfection by later teams.

Then the roving forward was discussed. I got a surprise when I was told emphatically that I was not the man. Mr Chapman said: "We want you up in attack scoring goals. You have the height and the stamina.'

We talked about other players until Mr Chapman said: "Well, it's your plan, Charlie, have you any suggestions to make?"

Then it occurred to me that I had seen, in practice games and playing for the second team, an inside-forward who was likely to fill the role. He was Andy Neil, a Scot who was getting on in years but who could kill a ball instantly and pass accurately.

So I said: "Yes, I suggest Andy Neil as the right man. He has a football brain and two good feet."

Finally, after a lot of argument, it was decided that Neil should be the first schemer-in-chief. And I must say he made a very good job of it for nearly the rest of that season.

Thus the Arsenal plan was brought into existence. It has been copied by most clubs.

(15) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

It looked as if neither side was going to score. Then seventeen minutes before the end, Dan Lewis, Arsenal goalkeeper, made the tragic slip that sent the Cup to Wales.

Hugh Ferguson, Cardiff centre-forward, received the ball about twenty yards from goal. He shot, a low ball that went, at no great pace, straight towards the goalkeeper. Lewis went down on one knee for safety. He gathered the ball in his arms. As he rose, his knee hit the ball and sent it out of his grasp. In trying to retrieve it, Lewis only knocked it further towards the goal.

The ball, with Len Davies following up, trickled slowly but inexorably over the goal-line with hardly enough strength to reach the net. It was a bitter set-back.

Even after that, Arsenal had a chance of pulling the game out of the fire. Outside-left Sid Hoar sent across a long, high centre. Tom Farquharson, Cardiff goalkeeper, rushed out to meet the danger. The ball dropped just beside the penalty spot and bounced high above his outstretched fingers.Jimmy Brain and I rushed forward together to head the ball into the empty goal. At the last moment Jimmy left it to me. I unfortunately left it to him. Between us, we missed the golden opportunity of the game.

(16) Simon Inglis, The Best of Charles Buchan's Football Monthly(2006)

Six foot tall with long legs and a loping gait, Buchan developed into a gifted and prolific inside-forward, scoring 224 goals in 413 appearances for Sunderland (a club record which still stands). The tally would have been higher had it not been for the outbreak of war. Typical of his generation, in A Lifetime in Football (first serialised in Football Monthly, then published in 1955), he skirted over his experiences at the Somme and Passchendaele, preferring instead to recall matches played with his army chums.

Apparently unscathed, physically or emotionally, Buchan returned from the trenches to resume his scoring feats with Sunderland in 1918, whilst also teaching part-time and setting up a sports goods shop in the town in 1920. By then he was married to a Wearside girl, Ellen, and had two children. He also started contributing articles to the local press, unusually without the intercession of a ghost writer.

But stand out though he did, both on and off the pitch, regular England honours eluded Buchan. Perhaps because of his chippy manner, he won only six caps, to go with his one Championship medal and FA Cup Final loser's medal, both earned in 1913.