Football and Trade Unionism

The Football Association was established in in October, 1863. Percy Young, has pointed out, that the FA was a group of men from the upper echelons of British society: "Men of prejudice, seeing themselves as patricians, heirs to the doctrine of leadership and so law-givers by at least semi-divine right."

In 1885 it was decided by the FA that clubs could play professionals in the FA Cup competition. It was not long before football clubs had large wage bills to play. It was therefore necessary to arrange more matches that could be played in front of large crowds. In March, 1888 it was suggested that "ten or twelve of the most prominent clubs in England combine to arrange home and away fixtures each season."

The following month the Football League was formed. It consisted of six clubs from Lancashire (Accrington, Blackburn Rovers, Burnley, Everton and Preston North End) and six from the Midlands (Aston Villa, Derby County, Notts County, Stoke, West Bromwich Albion and Wolverhampton Wanders).

Professional football was extremely successful and after a few years had over 30 members. The Football Association was determined to keep professional players under its control. In 1893 a regulation was introduced that compelled all professional players to register annually with the FA. No player was allowed to play until he was registered, nor was he free to change clubs during the same season without the FA's permission.

The Football League then introduced a new rule that stated that any professional player who wished to move on to another club had to obtain the permission of his present club. The Football League also insisted that once signed, a player was tied to his team for as long as the club wanted him. Therefore, if a player refused to sign a new contract at the beginning of the season, he could not sign for no one else unless the club gave permission.

This measures introduced in 1893 created the transfer system that still exists today. However, in 1893, the players were not free to negotiate a new contract on anything like equal terms with their employers. The Football League had in fact abolished the free market and clubs could now reduce player wages without losing their services.

One of the consequences of these measures was that several top players moved to clubs in the Southern League. The Football League responded by trying to persuade these clubs to join their cartel.

In September, 1893, Derby County proposed that the Football League should impose a maximum wage of £4 a week. At the time, most players were only part-time professionals and still had other jobs. These players did not receive as much as £4 a week and therefore the matter did not greatly concern them. However, a minority of players, were so good they were able to obtain as much as £10 a week. This proposal posed a serious threat to their income.

Some of these top players joined together to form a trade union. This included Bob Holmes and Jimmy Ross of Preston North End, John Devey of Aston Villa, John Somerville of Bolton Wanderers, Hugh McNeill of Sunderland, Harry Wood of Wolverhampton Wanderers and John Cameron of Everton. Other players who took a leading role in the union included Tom Bradshaw (Liverpool), James McNaught (Newton Heath), Billy Meredith (Manchester City), John Bell (Everton), Abe Hartley (Liverpool), Johnny Holt (Everton) and David Storrier (Everton).

In February 1898, these players announced the formation of Association Footballers' Union (AFU). Jack Bell became chairman of the union. The secretary of the AFU, John Cameron, announced that the union had 250 members. Cameron pointed out that their main objective was that they "wanted any negotiations regarding transfers to be between the interested club and the player concerned - not between club and club with the player excluded". John Devey added: "We're not taking up the question of wages and we are not talking any strike business."

The AFU was badly wounded by the decision of several members of the committee to seek higher wages in the Southern League. This included the AFU secretary John Cameron, who joined Tottenham Hotspur for the 1898-99 season. Tom Bradshaw also joined Spurs, whereas other leading figures in the union who left the Football League included Harry Wood and Abe Hartley (Southampton), Johnny Holt (Reading) and Jack Bell and David Storrier who joined Celtic.

Bob Holmes, who became the chairman of the AFU, gave an interview to the Lancashire Daily Post where he admitted the union was in serious trouble: "I am not quite sure that we shall succeed in attaining all the objects with which we set out; it is not a certainty that we shall carry any... The break-up of the Everton team as we knew it last season may have a good deal in influencing the future of the Union. With John Cameron, Jack Bell, Robertson, Holt, Stewart, Storrier, Meecham of Everton as well as Hartley and Bradshaw of Liverpool gone, our centre has lost strength. Liverpool was our headquarters, you know, and our registered offices were there. But the secretary, John Cameron, has gone to London and Bell the chairman will not, as far as I know, play for anybody."

Charles Saer, who replaced John Cameron as secretary of the AFU. A former player with Blackburn Rovers, Saer now worked as a schoolteacher. His negotiations with the Football League ended in failure and in December, 1898, Saer resigned as secretary "as his scholastic duties precluded the possibility of his devoting the necessary time to the office".

In May 1900 the Football Association passed a rule at its AGM that set the maximum wage of professional footballers playing in the Football League at £4 a week. It also abolished the paying of all bonuses to players.

In the 1903-04 season Manchester City finished in second place in the First Division. They also won the FA Cup in 1904 when they beat Bolton Wanderers in the final at Crystal Palace. The only goal of the game was scored by the great Billy Meredith.

The Football Association was amazed by Manchester City's rapid improvement and that summer they decided to carry out an investigation into the way the club was being run. However, the officials only discovered some minor irregularities and no case was brought against the club.

The following season Manchester City again challenged for the championship. City needed to beat Aston Villa on the final day of the season. Sandy Turnbull gave Alec Leake, the Villa captain, a torrid time during the game. Leake threw some mud at him and he responded with a two-fingered gesture. Leake then punched Turnbull. According to some journalists, at the end of the game, Turnbull was dragged into the Villa dressing-room and beaten-up. Villa won the game 3-1 and Manchester City finished third, two points behind Newcastle United.

After the game Alec Leake claimed that Billy Meredith had offered him £10 to throw the game. Meredith was found guilty of this offence by the Football Association and was fined and suspended from playing football for a year. Manchester City refused to provide financial help for Meredith and so he decided to go public about what really was going on at the club: "What was the secret of the success of the Manchester City team? In my opinion, the fact that the club put aside the rule that no player should receive more than four pounds a week... The team delivered the goods, the club paid for the goods delivered and both sides were satisfied."

The Football Association was now forced to carry out another investigation into the financial activities of Manchester City. They discovered that City had been making additional payments to all their players. Tom Maley was suspended from football for life. Seventeen players were fined and suspended until January 1907.

Manchester City was also forced to sell their players and at an auction at the Queen's Hotel in Manchester. The Manchester United manager, Ernest Mangnal signed the outstandingly gifted, Billy Meredith for only £500. Mangnal also purchased three other talented members of the City side, Herbert Burgess, Sandy Turnbull and Jimmy Bannister.

Billy Meredith was upset by the way that the clubs treated their players. Jimmy Ross played with Meredith at Manchester City until his early death in 1902. Despite his successful football career, Ross had been unable to save any money for his wife and children.

Another of Meredith's friends at Manchester City, left-back David Jones, died in 1902, after suffering an injury during a pre-season game. The club claimed he was not "working" at the time as the game was a friendly, even though a paying crowd of 20,000 people watched the game. Jones's widow and children were left with no insurance cover and had to rely on the proceeds of a collection and a benefit match with Bolton Wanderers. According to Meredith, the game raised very little money for the family.

In April 1907 Thomas Blackstock, a colleague at Manchester United, collapsed after heading a ball during a reserve game against St. Helens. 25 year old Blackstock died soon afterwards. An inquest into his death returned a verdict of "Natural Causes" and once again a football player's family received no compensation.

when he created the Association Football Players Union (January 1909)

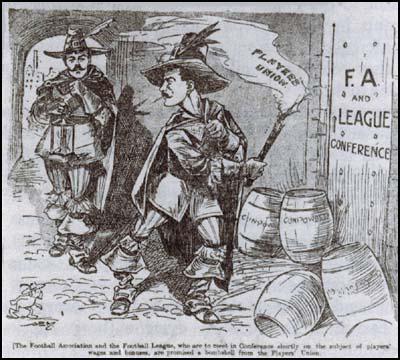

In 1907 Billy Meredith and several colleagues at Manchester United, including Charlie Roberts, Charlie Sagar, Herbert Broomfield, Herbert Burgess and Sandy Turnbull, decided to form a new Players' Union. The first meeting was held on 2nd December, 1907, at the Imperial Hotel, Manchester. Also at the meeting were players from Manchester City, Newcastle United, Bradford City, West Bromwich Albion, Notts County, Sheffield United, and Tottenham Hotspur. Jack Bell, the former chairman of the Association Footballers' Union (AFU) also attended the meeting.

Herbert Broomfield was appointed as the new secretary of the Association Football Players Union (AFPU). It was decided to charge an entrance fee of 5s plus subs of 6d a week. Billy Meredith chaired meetings in London and Nottingham and within a few weeks the majority of players in the Football League had joined the union. This included Andrew McCombie, Jim Lawrence and Colin Veitch of Newcastle United who were to become important figures in the AFPU. Evelyn Lintott, who came from a wealthy family and therefore played as an amateur, joined the AFPU and later became its chairman.

The AFPU also got support from administrators of the clubs. John J. Bentley (president) and John Henry Davies (chairman) of Manchester United joined the campaign to abolish the £4 ceiling on wages.

When Frank Levick of Sheffield United died aged 26 in 1908, the AFPU sent his family £20. They also entered into negotiations with his club about the compensation to be paid to his wife. The AFPU also explored the ways that football players could make use of the Workman's Compensation Act (1906).

At the 1908 Annual General Meeting the Football Association decided to reaffirm the maximum wage. However, they did raise the possibility of a bonus system being introduced whereby players would receive 50% of club profits at the end of the season.

In November 1908 Thompson's Weekly News announced that several leaders of the AFPU, including Billy Meredith, Jim Lawrence and Colin Veitch, would be writing regular articles for the newspaper. For the next six years, this newspaper with a circulation of 300,000, provided a forum for the views of union officials.

The AFPU continued to have negotiations with the Football Association but in April 1909 these came to an end without agreement. In June the FA ordered that all players should leave the AFPU. They were warned that if they did not do so by the 1st July, their registrations as professionals would be cancelled. The AFPU responded by joining the General Federation of Trades Unions.

Most players resigned from the union. All 28 professionals at Aston Villa signed a public declaration that they had left the AFPU and would not rejoin until given permission by the FA. However, the whole of the Manchester United team refused to back down. As a result they were all suspended by their club. The same thing happened to seventeen Sunderland players who also refused to leave the AFPU.

The players put their careers in jeopardy by staying in the union. As Charlie Roberts, the Manchester United captain pointed out: "I had a benefit due with a guarantee of £500 at the time and if the sentence was not removed I would lose that also, besides my wages, so that it was quite a serious matter for me."

John J. Bentley the president of Manchester United and the Football League and vice president of the Football Association, who had earlier supported the abolition of the maximum wage, now attacked the activities of the AFPU. "The very suggestion of a strike of footballers shows the meanness of the motives behind it and in my judgement cannot be too strongly condemned."

Colin Veitch, who had resigned from the AFPU in order to carry on negotiations with the Football Association, led the struggle to have players reinstated. At a meeting in Birmingham on 31st August 1909, the FA agreed that professional players could be members of the AFPU and the dispute came to an end.

Billy Meredith saw the decision as a defeat for the Association Football Players Union: "The unfortunate thing is that so many players refuse to take things seriously but are content to live a kind of schoolboy life and to do just what they are told ... instead of thinking and acting for himself and his class."

Charlie Roberts agreed with Meredith: "As far as I am concerned, I would have seen the FA in Jericho before I would have resigned membership of that body, because it was our strength and right arm, but I was only one member of the Players' Union. To the shame of the majority they voted the only power they had away from themselves and the FA knew it."

When the Manchester United team played in the first match of the season on 1st September, 1909, they all wore AFPU arm-bands. However, it took six months for the players to receive their back wages. Charlie Roberts never got his benefit match and several union activists were never picked again to play for their country.

After the First World War professional footballers received a maximum weekly wage of £10. In 1920 the Football League Management Committee proposed a reduction to £9 per week maximum. Buchan was one of those who called for the AFU to resort to strike action. However, large numbers of players resigned from the union and the Football League was able to impose the £9 maximum wage. The following year it was reduced to £8 for a 37 weeks playing season and £6 for the 15 weeks close season.

Despite the efforts of the Players' Union, there was no other change until 1945 when the maximum close season wage was increased to £7 per week. Two years later a National Arbitration Tribunal was established. It decided that the maximum wage should be raised to £12 in the playing season and £10 in the close season. The minimum wage for players over 20 was set at £7.

The maximum wage was increased to £14 (1951), £15 (1953), £17 (1957) and £20 (1958). The players made further wage demands in 1960 and when these were backed by a threat to strike on 14th January, 1961. The Football League responded by abolishing the maximum wage and increasing the minimum wage to £15.

Primary Sources

(1) John Cameron, interviewed in Football Chat (December 1899)

In my opinion, the FA have not acted with their usual discretion over the wages question. Surely the matter of wages is for club legislation alone? Every club knows, or ought to know, what it can afford to pay and if they go above their means I should certainly call it bad management and the club who does that deserves to be stranded. I noticed with a little amusement that it was those clubs that had paid more than they could afford that fought hard to carry the new measures through. Now look here, how would any man in business like to have his wages reduced by 25% if his employers could well afford better terms?

(2) John Cameron, interviewed in Football Chat (November 1900)

Time has made the system almost indispensable to the League clubs. Their finances are wrapped around it for their players are looked upon practically as assets; and when a club is paid a large sum of money for a player you cannot blame them for so doing. They say the system working from the club point of view is a good one, for it gives the clubs a great hold upon the players and perhaps saves a wholesale shifting of players every year which would not be good for the game.... I admit there is some truth in that, but the price is much too heavy on the players. In the Southern League there is no transfer system and yet Southampton, Portsmouth and my own club Tottenham Hotspur and others retain their players year after year; so why not the League?

(3) John Harding, For the Good of the Game (1991)

In the years between 1901 and the start of the First World War, the Football League strengthened its grip on the professional game, taking in popular Southern clubs such as Fulham, Chelsea, Tottenham and Bristol City. The Southern League, weakened by such defections, pressed for amalgamation but was turned away, although it would eventually come to an arrangement regarding transfers.

Meanwhile, the maximum wage and the transfer system seemed not to have had the desired effect where winners and losers were concerned - the hoped for `equality' remaining a pipe-dream. The `Super League' of the 1890s - Aston Villa, Sunderland, Newcastle United and Everton - was joined by Liverpool, Sheffield Wednesday and the two Manchester teams, City and United, and between them these eight teams won all the League titles up to the war. They also took fifty per cent of Cup wins, and between the years 1904 and 1914 there was not a Cup Final that did not feature either one or two of the 'Super Eight'.

(4) Billy Meredith, Thompson's Weekly News (December 1909)

What is more reasonable than our plea that a footballer with his uncertain career should have the best money that he can earn? If I can earn £7 a week, why should I be debarred from receiving it? I have devoted my life to football and I have become a better player than most because I have denied myself much that men prize. A man who takes the care of himself that I have ever done and who fights the temptations of all that can injure the system surely deserves some recognition and reward!

They (the players) are, as a whole, an over-generous careless race who do not heed the morrow or prepare for a rainy day as wise men would. This trait in the character of the players has been taken advantage of over and over again by club secretaries in England. Many a lad has been tricked into signing on by vague verbal promises deliberately made to be forgotten once the ink was dry on the form. It is only recently that with steady improvement in the class of men playing the game as professionals the players have seen the folly of the careless life and have realized that they have too long put up with indifferences and injustices of many kinds. The only way to alter this state of things was by united action hence the formation and success of the Players' Union with its 1300 paying members at the end of the first year...

What opens the door to irregular payments is the rank injustice of the £4 per week limit and of the transfer system which gives a club £1000 for a player and allows the latter - one really ought to call him the goods -£10. If the £10 went to the club and the £1000 to the man whose ability it is the agreed value of, there would be more justice in it.

(5) John Harding, For the Good of the Game (1991)

In an article he wrote in December 1908 for the Athletic News, C. E. Sutcliffe violently attacked the Players' Union's "amazing proposals". They were, he said, "but the outward and visible sign of their inward greed". The Union's resolutions were "contemptible clap-trap"; "immoderate and unreasonable", and to grant them would be "suicide" for football, and would lead back to the days when such a spirit of selfishness was ruining the game and the clubs".

Just why Sutcliffe should have responded in such a way appeared a mystery to many. A few months prior to his outburst he had personally presented his own bonus scheme to the Players' Union Management Committee and although he had subsequently expressed impatience with the Union for not having expressed an opinion on the matter, it had been made clear to him that this was not a condemnation of his ideas - simply that the Union had no appropriate platform, being unrepresented on the FA council, and would wait until its AGM before stating its opinion.

Furthermore, the Union's subsequent opposition to the maximum wage was shared by the FA and a majority of First Division clubs. Thus, in attacking the Union in such sneering and insulting terms, Sutcliffe was behaving, on the face of it, rather oddly.

But Sutcliffe had a clear vision, that of the Football League system as it then stood, sacrosanct and inviolate. The continual arguing, lobbying and pressure by the bigger clubs for wage reform clearly irked him. Talk of a Super-League was both unsettling and distasteful to him. His own club, Burnley, would not feature in such a breakaway; it was too small and vulnerable. At that very moment it was languishing in the lower half of the Second Division and struggling financially. The nationwide craze for roller-skating could only damage clubs like Burnley; it was said that the town had six roller-skating rinks taking over £1000 a week.

Thus the idea of players being free to demand more money for their services must have been genuinely disturbing. Add to the fact that famous club chairmen were helping the new Union and perhaps Sutcliffe's venom can be understood.

Response to his outburst, however, was at first muted. No official Union reply was forthcoming but within days, Colin Veitch, Newcastle captain and a future Union chairman, did take him to task in his Weekly News column - though politely and almost apologetically.

Veitch pointed out the obvious - that the Union was not alone in advocating abolition of the wage limit, that changes to the present system would be welcomed if that was all that could be expected. Indeed, Veitch wondered what exactly the Union could do, "for to have suggested another scheme in its place would surely have placed it [the Union] in an illogical not to say farcical situation".

But Veitch was more concerned to answer Sutcliffe's more serious charge - that professional players could not be trusted, that they were not to be regarded with the respect that professional men might automatically deserve. For this, one senses, was the real issue - the status of professional players and their right to stand as equals alongside administrators, managers, directors, etc. and to have a voice in their own affairs.

Sutcliffe clearly preferred to see the players as they had supposedly been in the 1880s - mercenaries, pirates, racing from club to club grabbing whatever they could. Veitch was adamant that those days had gone: "The type of man in the professional ranks of today is of another stamp altogether to the professional of twenty years ago and you must not saddle the misdeeds of his predecessors upon his shoulders."

(6) Colin Veitch, Weekly News (December, 1908)

The players are joined in brotherhood through the agency of the Players' Union and I am quite at one with him (Sutcliffe) that the Union should take strong measures with any member found guilty of offences detrimental to the true interests of the game and incidentally harmful to the rest of the professionals by the same process.... It is the duty of the present-day professional to vindicate himself in the eyes of everyone, even those whose prejudices prove a formidable barrier to understanding, and the Players' Union can help in the manner suggested.

(7) Billy Meredith, Thompson's Weekly News (July 1909)

If I were a wealthy man tomorrow I should spend my summer just as does Herbert Claude Broomfield.... In a lovely country spot on the edge of a pine forest in front of a large mere stands a little gaily painted building that no one can see from the road. It has two rooms, the kitchen has a fine range, the drawing room is pannelled and painted. There are four bunks and steps outside lead up to the roof which has a deck. It is the captain's cabin from a ship and is made into an ideal bungalow. There is a pretty garden and steps lead on to a fine tennis court. Here Broomfield and two chums live sleeping under the sky on warm nights, in the bunks when the air is colder. Tennis, golf, swimming, football and a punch-ball - all can be had on the spot. A gramophone sings the trio to sleep. They all cycle too and have created a sensation in their time in all three countries when touring on a triplet that bears motor-cycle tyres.

(8) John Harding, For the Good of the Game (1991)

The maximum wage, imposed in 1901, was almost impossible to adhere to for ambitious big city clubs like Manchester City. The Manchester public, not to say businessmen and local worthies, were anxious for success. That one of the nation's largest cities, home of the industrial revolution, should be unable to produce a prestigious team seemed absurd, even insulting. Such expectations made for impatience, which in turn led to the bending of many rules.

When First Division status - painfully earned on a shoestring budget - was briefly lost in 1901, wholesale changes occurred at Hyde Road, Manchester City's original home. Backed by newspaper millionaire Edward Hulton's money, Scotsman Tom Maley rapidly bought and built a successful new side that swept back into the First Division and took the FA Cup to Manchester for the first time the following year.

(9) Herbert Broomfield, letter to a member of the Association Football Players Union (27th July, 1909)

It is useless for members of the FA to go about lecturing on the purity of the game or its improvement whilst those men playing under its rules are relegated to the position of slaves.

The despotism and tyranny of the Empire has been its downfall. If such methods are not approved of in Turkey I am quite sure they will not be tolerated in civilized England and for this reason I feel sure of victory.

(10) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

I was chosen as inside-right for the first home game, against Plymouth Argyle at Osborne Road. But I had another disturbing shock before I was allowed to kick a ball.

When I walked into the dressing-room, about an hour before he kick-off, George Ryder, our inside-left and father of Terry Ryder, now a professional, came up to me and said: "We're waiting for word that the players are to go on strike. Will you join with the rest of the boys?"

Though I had not then joined the Players' Union, which was discussing the problem, I replied: "Yes, I'll do exactly as the others. In fact, I have no choice, if the rest aren't going to turn out."

We spent anxious minutes waiting, before the word came through that the strike was off. It had been settled in Manchester where those great players, Charlie Roberts and Billy Meredith who became great friends of mine later on-bore the brunt of the proceedings. I joined the Union the next week.

(11) John Harding, For the Good of the Game (1991)

Charlie Roberts had been the first to hear that he and his team were to be suspended for publicly stating that they would not resign from the Union: he had read about it in the evening papers delivered to his newsagent's shop: "I had a benefit due with a guarantee of £500 at the time and if the sentence was not removed I would lose that also, besides my wages, so that it was quite a serious matter for me."

The club had told him nothing, however, so he and the rest of the United team turned up as usual at the ground the following Friday to see whether they would receive any pay. No one was prepared to talk to them except an office boy who told them there was no money.

"'Well, something will have to be done,' said Sandy Turnbull as he took a picture off the wall and walked out of the office with it under his arm. The rest of the boys followed suit, and looking-glasses, hairbrushes and several other things were for sale a few minutes later at a little hostelry at the corner of the ground.

I stayed behind a while with the office boy who was in a terrible state over the players taking things away and he was most anxious to get them back before the manager arrived. `Come along with me and I will get them for you,' I said. 'It's only one of their little jokes.' I soon recovered the lost property for him. But it was funny to see those players walking off the ground with pictures, etc. under their arms."

Being barred from the ground, the Manchester men decided to continue their pre-season training at Fallowfield, the Manchester Athletic Club ground, secured for them by Broomfield. This turned out to be a publicity coup for the Union, as reporters and photographers arrived to interview and photograph the famous rebels. During one such session Roberts had the happy inspiration that helped create a legend:

"After training a day or two a photographer came along to take a photo of us and we willingly obliged him. Whilst the boys were being arranged I obtained a piece of wood and wrote on it, 'Outcasts Football Club 1909' and sat down with it in front of me to be photographed. The next day the photograph had a front page of a newspaper, much to our enjoyment, and the disgust of several of our enemies."

(12) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

At the end of the first post-war season - 1919-20 - trouble broke out concerning players' wages. I was on the Players' Union Committee at the time and we wanted the weekly wage stabilized at £10 per week maximum.

The League Management Committee, the mouthpiece of the clubs, proposed a reduction to £9 per week maximum. The Union held a delegates' meeting in Manchester at which it was unanimously decided to call a strike.

The delegates were instructed to go back to their teams and vote "yes or no" on strike action and come back to another meeting on the following Monday.

In the meantime, however, several teams re-signed en bloc. So there could be no strike. The upshot was they had to accept the League's terms £9 per week maximum.

Worse followed at the end of the following season, 1920-1, when the wages were reduced to a maximum of £8 for a 37 weeks playing season and £6 for the 15 weeks close season.

All the time, the Union were pressing for the abolition of wage restrictions. They called for a "no limit" wage but the clubs would have none of it.

If the players had pressed their claims in the summer of 1920, I am sure they would have got their terms. As it was, they failed to get together as a body and were overruled.

Much the same is going on today. The Union are pressing for the abolition of the maximum wage and new contracts for players. They will never get them unless they work together in closer harmony.