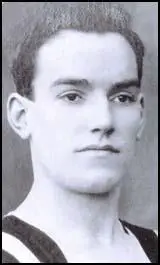

Colin Veitch

Colin Veitch was born in Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne, on 22nd May, 1881.He played for Rutherford College before joining Newcastle United in 1899.

Veitch preferred playing in midfield but over the next 16 seasons he played in every position except goalkeeper, left-back and outside left. He made his debut at nineteen. However, he did not become a regular until the 1902-1903 season.

Paul Joannou points out in The Black 'n' White Alphabet: "He (Veitch) was a thoughtful player, an expert tactician and always had control of the ball and used it to good purpose. He also often found the net for the Magpies and can be identified as perhaps the leading spirit behind the club's Edwardian success."

Newcastle United won the Football League championship in the 1904-05 season. The club also reached the FA Cup Final that year but was beaten by Aston Villa 2-0. The attendance of 101,117 remains the largest crowd to watch Newcastle play. Newcastle also got to the 1906 FA Cup Final. However, this time they were beaten by Everton 1-0.

Veitch won his first international cap playing for England against Ireland on 17th February, 1906. England won 5-0 and Veitch retained his place for the games against Wales and Scotland. He also played in two of the three games in the following season.

Newcastle United also won the First Division championships in the 1906-07 and 1908-09 seasons. They also won the FA Cup Final against Barnsley in 1910.

Veitch was also a leading figure in the Association Football Players Union (AFPU). Veitch along with Billy Meredith and Jim Lawrence wrote regular articles for the Thompson's Weekly News. This newspaper, with a circulation of 300,000, provided a forum for the views of union officials.

The AFPU continued to have negotiations with the Football Association but in April 1909 these came to an end without agreement. In June the FA ordered that all players should leave the AFPU. They were warned that if they did not do so by the 1st July, their registrations as professionals would be cancelled. The AFPU responded by joining the General Federation of Trades Unions.

Most players resigned from the union. All 28 professionals at Aston Villa signed a public declaration that they had left the AFPU and would not rejoin until given permission by the FA. However, the whole of the Manchester United team refused to back down. As a result they were all suspended by their club. The same thing happened to seventeen Sunderland players who also refused to leave the AFPU.

Colin Veitch, who resigned from the AFPU in order to carry on negotiations with the Football Association, led the struggle to have players reinstated. At a meeting in Birmingham on 31st August 1909, the FA agreed that professional players could be members of the AFPU and the dispute came to an end. However, like most of the international players who took part in this dispute, Veitch never played for England again.

Veitch served as chairman of the Association Football Players Union until he retired from football on the outbreak of the First World War. He had scored 49 goals in his 322 games for the club. He joined the British Army and reached the rank of 2nd Lieutenant.

A committed socialist, Veitch was urged to stand for the House of Commons by the Labour Party. Veitch, who was a close friend of George Bernard Shaw, was also heavily involved in the Newcastle Playhouse and the Newcastle Operatic Society. As Paul Joannou points out in The Essential History of Newcastle United: "He (Veitch) was an educated man of many talents: an articulate scholar, musician, actor, playwright and politician".

After the war Veitch returned to Newcastle United to work on the coaching staff. In 1924 he was put in charge of the Newcastle Swifts, the club's junior team. He also managed Bradford City between August 1926 and January 1928. Later he worked as a journalist for the Newcastle Chronicle. However, in 1929 he was banned from St. James Park for making critical comments of the club.

Colin Veitch died on 27th August 1938 whilst convalescing in Switzerland after having contracted pneumonia.

Primary Sources

(1) Paul Joannou, The Black 'n' White Alphabet (1996)

A man of many talents, Colin Veitch was an articulate scholar, musician, actor, playwright and very politically aware. He was a leading activist of the Players' Union's cause at a time when they struggled to survive, the organisation's chairman from 1911 to 1918 and was also nominated to stand for Parliament as a socialist. Married to an actress, he was heavily involved in the Newcastle Playhouse, Newcastle Operatic Society and Clarion Choir, and counted George Bernard Shaw among his close friends.

(2) John Harding, For the Good of the Game (1991)

In an article he wrote in December 1908 for the Athletic News, C. E. Sutcliffe violently attacked the Players' Union's "amazing proposals". They were, he said, "but the outward and visible sign of their inward greed". The Union's resolutions were "contemptible clap-trap"; "immoderate and unreasonable", and to grant them would be "suicide" for football, and would lead back to the days when such a spirit of selfishness was ruining the game and the clubs".

Just why Sutcliffe should have responded in such a way appeared a mystery to many. A few months prior to his outburst he had personally presented his own bonus scheme to the Players' Union Management Committee and although he had subsequently expressed impatience with the Union for not having expressed an opinion on the matter, it had been made clear to him that this was not a condemnation of his ideas - simply that the Union had no appropriate platform, being unrepresented on the FA council, and would wait until its AGM before stating its opinion.

Furthermore, the Union's subsequent opposition to the maximum wage was shared by the FA and a majority of First Division clubs. Thus, in attacking the Union in such sneering and insulting terms, Sutcliffe was behaving, on the face of it, rather oddly.

But Sutcliffe had a clear vision, that of the Football League system as it then stood, sacrosanct and inviolate. The continual arguing, lobbying and pressure by the bigger clubs for wage reform clearly irked him. Talk of a Super-League was both unsettling and distasteful to him. His own club, Burnley, would not feature in such a breakaway; it was too small and vulnerable. At that very moment it was languishing in the lower half of the Second Division and struggling financially. The nationwide craze for roller-skating could only damage clubs like Burnley; it was said that the town had six roller-skating rinks taking over £1000 a week.

Thus the idea of players being free to demand more money for their services must have been genuinely disturbing. Add to the fact that famous club chairmen were helping the new Union and perhaps Sutcliffe's venom can be understood.

Response to his outburst, however, was at first muted. No official Union reply was forthcoming but within days, Colin Veitch, Newcastle captain and a future Union chairman, did take him to task in his Weekly News column - though politely and almost apologetically.

Veitch pointed out the obvious - that the Union was not alone in advocating abolition of the wage limit, that changes to the present system would be welcomed if that was all that could be expected. Indeed, Veitch wondered what exactly the Union could do, "for to have suggested another scheme in its place would surely have placed it [the Union] in an illogical not to say farcical situation".

But Veitch was more concerned to answer Sutcliffe's more serious charge - that professional players could not be trusted, that they were not to be regarded with the respect that professional men might automatically deserve. For this, one senses, was the real issue - the status of professional players and their right to stand as equals alongside administrators, managers, directors, etc. and to have a voice in their own affairs.

Sutcliffe clearly preferred to see the players as they had supposedly been in the 1880s - mercenaries, pirates, racing from club to club grabbing whatever they could. Veitch was adamant that those days had gone: "The type of man in the professional ranks of today is of another stamp altogether to the professional of twenty years ago and you must not saddle the misdeeds of his predecessors upon his shoulders."

(3) Colin Veitch, Weekly News (December, 1908)

The players are joined in brotherhood through the agency of the Players' Union and I am quite at one with him (Sutcliffe) that the Union should take strong measures with any member found guilty of offences detrimental to the true interests of the game and incidentally harmful to the rest of the professionals by the same process.... It is the duty of the present-day professional to vindicate himself in the eyes of everyone, even those whose prejudices prove a formidable barrier to understanding, and the Players' Union can help in the manner suggested.