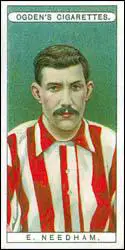

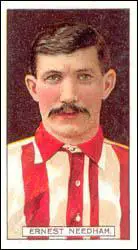

Ernest Needham

Ernest Needham was born at Whittington Manor on 21st January 1873. He played local football for Waverley and Staveley before joining Sheffield United in 1892.

A left-half, Needham made his debut in the 1892-93 season and played an important role in the club's promotion to the First Division of the Football League.

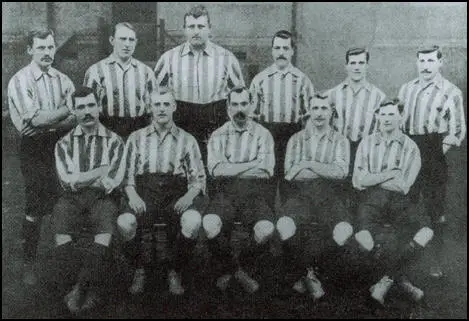

An outstanding player, he won his first international cap against Scotland on 7th April, 1894. England drew the game 2-2. The following season he was appointed captain Sheffield United. Over the next couple of years the club recruited some top players including William Foulke, Ernest Needham, Walter Bennett and George Hedley.

In 1895 Needham had his wages increased to £3 a week, which included a retainer wage over the summer. Needham and his team mates were also paid a ten-shilling (50p) bonus for an away win, and five shillings for a home win or away draw. Records show that for key games the players were paid £5 for a win. At the time, the average wage of a working man was about £1. However, someone with specialist skills could earn up to £2.50 a week.

In the 1896-97 season Sheffield United were runners-up behind the double-winning Aston Villa. The team conceded just 29 goals throughout the campaign and the club had easily the best defensive record in the Football League.

Sheffield United, led by Ernest Needham, won the First Division championship of the Football League in the 1897-1898 season. The club struggled the following year in the league but the team beat Derby County in the 1899 FA Cup Final.

Needham was in great form in the 1899-1900 season and once again Sheffield United had the best defensive record in the league. The club finished in second place to Aston Villa.

The following season Needham was a member of the Sheffield United team that reached the 1901 FA Cup Final against Tottenham Hotspur. Needham and the other players were on a £10 win bonus. However, the Southern League side was on a promise of £25 a man if they won the cup. The game ended in a 2-2 draw. However, Spurs won the replay 3-1.

Needham was also a talented cricketer and along with his great friend, William Foulke, played for Derbyshire in the County Cricket Championship.

In 1901 Ernest Needham published the book Association Football. It included chapters on Football as Sport, Forwards and Forward Play, Back and Half-Back Play, Training and Captaincy, The League and its Successes, Past and Present Football and Some Promising Players. It also provided an account of the 1900-01 season.

Needham was a member of the Sheffield United team that played Southampton in the 1902 FA Cup Final. Sheffield took an early lead but Southampton scored a controversial equalizer and the game was drawn. C. B. Fry wrote in the Southern Echo: "The outstanding feature of the match was the grand goalkeeping of Foulke. he made a number of good saves, and on two or three occasions cleared the ball from what appeared impossible positions. Once, near the end, from a corner, he effected an absolute miracle with four or five men right on to him."

William Foulke was furious that the equalizing goal had been given after the game he went searching for the referee. The linesman, J. T. Howcroft, described how Frederick Wall, secretary of the Football Association, tried to placate the goalkeeper: "Foulke was exasperated by the goal and claimed it was in his birthday suit outside the dressing room, and I saw F. J. Wall, secretary of the FA, pleading with him to rejoin his colleagues. But Bill was out for blood, and I shouted to Mr. Kirkham to lock his cubicle door. He didn't need telling twice. But what a sight! The thing I'll never forget is Foulke, so tremendous in size, striding along the corridor, without a stitch of clothing."

Walter Bennett was injured and could not take part in the replay. He was replaced by the young William Barnes on the wing. The game was only two minutes old when a massive clearing kick by Foulke reached George Hedley and Sheffield United took an early lead. Led by the outstanding Ernest Needham, Sheffield dominated play but Albert Brown managed to score a equalizer. Southampton began to apply pressure but according to the Athletic News, "Foulke was invincible". With ten minutes to go, Needham took a shot that the Southampton goalkeeper, John Robinson, could only block, and Barnes was able to hit the ball into the unguarded net. Sheffield won 2-1 and Foulke had won another medal.

Ernest Needham played his last international game for England on 3rd March, 1902. Over a eight year period he won 16 international caps and scored three goals for his country.

Needham retired from professional football in 1909. During his time at Sheffield United he scored 49 goals in 464 games. He continued to play cricket for Derbyshire in the County Cricket Championship until 1912. In total he scored 6550 runs, including seven centuries.

Ernest Needham died in 1936.

Primary Sources

(1) Ernest Needham, Association Football (1901)

Well-directed exercise is the chief factor in training for any sport. Here I might warn against a most common error. Too many youths and men play football to obtain exercise, but this is quite wrong: exercise should, nay, must precede match football, or harm from exposure and over-straining is bound to ensue. Still more, the untrained man blunders about the football field, throwing himself blindly into danger, and proving a frequent source of accident to himself and others. This is so well known to professional players that trainers take charge of first-class men at least a month before their first public appearance of the season. To get into condition at the beginning of the season is hard work, for while resting superfluous fat has accumulated, some muscles of locomotion have become more or less flabby, the circulatory system is torpid, and the chest muscles and organs of respiration are slow in their action. To counteract all this, we must at first have plenty of football practice to bring the muscles into obedience to the will, skipping, walking, and running to strengthen them, sprinting to cultivate speed, and three-quarter and mile runs to tone up heart and lungs. Indian clubs and dumbbells are occasionally used. These various exercises, used lightly at first, and gradually increased under experienced direction, will produce the necessary vigour and hardness, and bring the player into condition for match playing.

When once a man is "fit," and the season has commenced, less practice is needed, one or two days a week at kicking, more walking, and gentle exercise being sufficient to keep him up to the mark. The intelligent trainer now must see that proper food is used to restore exhausted energy, and lay up for future exertions. He knows that excessive wear and tear of the framework fills the body with worn-out substances. The muscles and blood are overcharged with broken-down tissue, almost to the extent of poisoning. Now, then, comes the time for rest and natural recuperation. Nature's efforts to expel foul matter must be assisted by baths, massage, etc., and only sufficient exercise indulged in to prevent any sudden running-down....

We all know that accidents will happen in the best regulated of sports (even pedestrians are not free from them); but accidents of a serious or fatal nature are very rare considering the thousands who play, and it is questionable whether the percentage does not compare favourably with those of other pastimes.

How to prevent them no hard and fast rule can be set down. They will occur in the simplest fashion at times, when on another occasion the player would have come off scot free. It is wonderful how many silly people there are who debar themselves from participation in the game through this score; and it is sheer nervousness. The man who declared that some people would scarcely go to bed because so many people died there annually may have been guilty of exaggeration, but he was not far wide of the mark after all.

When a player has the misfortune to meet with an accident (or, still worse, when one is killed) there is an outcry from the opponents of the game. Well, it is the true Englishman's love of danger which, rightly or wrongly, impels him to take part in a pastime in which there is a certain amount of risk; and the more risk, the more eager he is for the fray. It is only the "namby-pambys" who delight in drawing-room games. We should not have such heroes as Nelson, Wellington, and many others, if they had not "faced the music," so to speak.

What Englishman with an ounce of pluck will not brave danger? See the coal-miner in the case of an explosion, railwaymen in collisions, sailors on the sea, soldiers in battle. Would those men shirk a pastime because it was fraught with danger? They would not. It is characteristic of them to brave dangers.

(2) Ernest Needham, Association Football (1901)

The penalty kick is still a new feature to us, and points to the determination of the Association to have the game played in a gentlemanly manner. It was designed to prevent all underhand attempts at saving well-earned goals,and certainly the almost sure goal in which it would result should make it quite effective. Among some minor alterations in the rules we must notice the establishment of a close season for football, and its accompanying abolition of six-aside contests. The former will tend to preserve the interest in the chief competitions of the country, and insure players coming up to scratch after a good rest at the beginning of the season. Six-aside matches were, up to about eight years since, attractions - and good ones, too - at flower shows, sports, etc., and I have heard many players regret the easily-earned bags, boots, etc., that were given as prizes, but undoubtedly greater good accrues from their absence.

What a contrast would our players present to former times in the matter of outfit. I can quite easily remember the time when proper football boots were quite unknown, and when each man donned what to him seemed fit. Now we turn out our representatives in colours, and provide them with everything of the best to assist them as much as outside helps can in giving good exhibitions. We have changed all that for the better, and you may see that even the lad in the street recognizes our stripes or quarterings, and watches their progress up the well-known League ladders.

(3) J. A. H. Catton, The Story of Association Football (1926)

I have been scribbling about footballers from the days when I had some hair until now a comb is an encumbrance and scanty locks are silvered o'er with the toll of years. Seldom have players complained to me about what I have thought fit to set down.

Two instances to the contrary come to mind. When Sheffield United and Southampton met in the Final Tie for The Cup at the Crystal Palace in 1902 there was a curious incident, for when the second half was advanced and the United were leading by a goal scored by Common, Edgar Chadwick broke away and made a pass to Harry Wood, the father of Arthur Wood, who kept goal for Clapton Orient. The famous old Wolverhampton forward went on and scored. Thus the match was drawn-most unexpectedly.

At that time I had left the Press Box and was sitting on the pavilion near Mr. G.S. Sherrington, one of the vice-presidents of the Football Association, and Mr. P.A. Timbs, who was then on the Council. They turned and said that the goal was offside, but Tom Kirkham, of Burslem, the referee, gave a goal. I said that the ball grazed the knickers of Peter Boyle, the Sheffield United back, in transit. Strangely enough, John T. Howcroft, who was the linesman on the opposite side of the field to the grandstand, thought so, too.

The following Saturday the Final was replayed at the Crystal Palace, and I went down to the dressing cubicles in the pavilion to ascertain the teams before they went out. Peter Boyle saw me and most indignantly denied that the ball ever touched him, and threatened to do all manner of things with my poor body. No doubt he was annoyed and at the moment heated.

I felt the truth of what Lafcadio Hearn once said: "What is wanted in a time of embarrassment and danger is a good head not a strong arm." So I temporised about optical delusions and mistakes to which all men are subject.

Then there appeared in front of me a naked giant-one William Foulke, the Sheffield goalkeeper, who stood all six feet two inches and pulled down the scale at twenty stones. If ever man deserved the name of The Mountain he did. Foulke was good tempered and sought to quell the storm by humour. So he put himself in fighting position and said: "Come on, lad. You're just about my weight"-and I was a miserable five feet and under eleven stones. I could have laughed, but Boyle's brow was menacing.

The situation was far from pleasant, but Ernest Needham opened the door of his cubicle and pulled me inside. "Nudger" Needham surprised me by saying that I had left the Press Box and never saw the goal. I explained, and my peril passed. There is no doubt that I was mistaken-but two of the officials were the same.

(4) Alfred Gibson, commenting on Ernest Needham in 1906.

There is one thing which has made Earnest Needham stand out of the common run of halves; he is neither a constructive nor a destructive half-back alone; he is both at once. One moment you will see him falling back to the defence of his own goal, or checking the speedy rush of his wing; the next, he is up with his forwards, feeding them to a nicety, and always making the best of every opening. Where he gets his pace from is a mystery. He never seems to be racing, yet he must be moving at racing pace; he never seems to be exhausted, yet in a big game he is practically doing three men's work... This is one of the secrets of his greatness for very seldom when he has the ball is he deprived of it, whilst the accuracy of his wing passes, and the telling force of his punches straight across the field to an unprotected wing, spell danger to any kind of defence.

(5) Graham Phythian, Colossus: The True Story of William Foulke (2005)

As the teams made their way from the pitch, a Southampton fan decided to vent his frustration on Needham, hitting the Sheffielder in the face. Perhaps he chose Needham because of the half-back's small stature. If it were so, it were a grievous fault. Nobody present - with the single obvious exception - could have been a more redoubtable opponent in such a confrontation than hard-as-nails Needham. Normally the soul of diplomacy, the United captain retaliated with a left-right combination that wouldn't have disgraced Bob Fitzsimmons. At this point the spectator, concluding it might be a good idea to make himself scarce, turned and ran - into the arms of a couple of policemen. The next day back in Sheffield there was a rumour that it was Foulke who had hit back. But as the Monday's Sheffield Telegraph wryly commented: "The assailant may be glad it was only Needham."

(6) Ernest Needham, Association Football (1901)

The popular idea that football is a dangerous game will surely have to undergo modification, but we must acknowledge that it was formerly dangerous. Once broken limbs from kicks, and broken ribs from charges, were quite every-day occurrences, and, to a great extent, men went on the field with their lives in their hands. It is safe to say that now there is no more risk in playing, even a fast game, than there is in any other active sport.

Surely last season's freedom from accident in First Division matches is sufficient evidence of this. I do not remember that any player had a limb broken, and even the Second Division was almost equally free. The object of many changes in the rules has been to extend protection to those engaged, and especially to the goalkeeper. Never now can we see two or three men rush at this isolated guard, while another pops the ball through. To begin with, it is difficult to get near enough to him for a charge without the "off-side rule" coming into operation. Then, again, the last part of Rule 10 says, "The goalkeeper shall not be charged except when he is holding the ball, or obstructing an opponent"; and it is seldom, and not for long, that the custodian is in contact with the ball. It is safe to say that the goalkeeper is the best protected man on the field.