Goalkeeping

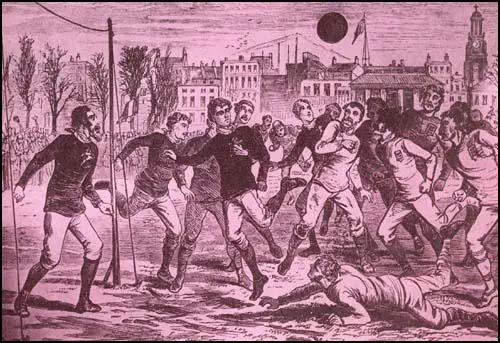

In 1848 a meeting of several public schools took place at Cambridge University to lay down the rules of football. Teachers representing Shrewsbury, Eton, Harrow, Rugby, Marlborough and Westminster, produced what became known as the Cambridge Rules. One participant explained what happened: "I cleared the tables and provided pens and paper... Every man brought a copy of his school rules, or knew them by heart, and our progress in framing new rules was slow."

Under the Cambridge Rules all players were allowed to catch the ball direct from the foot, provided the catcher kicked it immediately. However, they were forbidden to catch the ball and run with it.

Former pupils of the Sheffield Collegiate School established the Sheffield Football Club at Bramall Lane. In 1857 they published their own set of rules for football. These new rules allowed for more physical contact than those established in Cambridge. Players were allowed to push opponents off the ball with their hands. It was also within the rules to shoulder charge players, with or without the ball. If a player caught the ball, he could be barged over the line.

The Football Association was established in October, 1863. The aim of the FA was to establish a single unifying code for football. Ebenezer Cobb Morley was elected as the secretary of the FA. At a meeting on 24th November, 1863, Morley presented a draft set of 23 rules. These were based on an amalgamation of rules played by public schools, universities and football clubs.

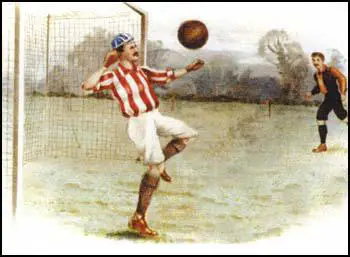

time the keeper wore the same colour shirt as the rest of the team.

The 1870s saw several changes to Football Association rules. In 1870 eleven-a-side games were introduced with the addition of a goalkeeper. In 1872 the FA published an updated set of laws. This made it clear that "a goal shall be won when the ball passes between the goal posts under the tape, not being thrown, knocked on, or carried." The new rules clearly distinguished between goalkeepers and other players: "A player shall not throw the ball nor pass it to another except in the case of the goalkeeper, who shall be allowed to use his hands for the protection of his goal... No player shall carry or knock on the ball; nor shall any player handle the ball under any pretence whatever."

The FA continued to adapt the rules of the game. In 1882 all clubs had to provide crossbars. Ten years later goal nets became compulsory. This reduced the number of disputes as to whether the ball had crossed the goal-line or passed between the posts.

Bob Roberts of West Bromwich Albion was the country's first star goalkeeper. He played in virtually every outfield position before eventually becoming the team goalkeeper. In his book, The Essential History of West Bromwich Albion, Gavin McOwan argues: "The 6ft 4in tall, 13-stone Roberts became known as the Prince of Goalkeepers... His hefty physique (he wore size 13 boots) was a huge asset in the days when forwards would try to steamroller keepers through the goal - with or without the ball." A local newspaper commented: "There is no player who has done more to make the Albion the club what it is than Bob Roberts. It is not only his cleverness between the uprights, but the coolness and direction of others."

John Gow made his debut for Blackburn Rovers against Sunderland on 11th October 1890. Blackburn took a 3-2 lead and with only minutes to go a Sunderland player hit a shot at goal. Gow, realising it was out of his reach, tugged at the crossbar and therefore ensuring a goal was not scored. Despite the protests of the Sunderland players, the referee refused to take action against Gow.

One of the most famous goalkeepers in British history was Ted Doig. He played for Arbroath in the Scottish League before joining Sunderland in 1890. Doig retained his place in the team for the whole of the 1890-91 season. He also played in every game the following season. That year Sunderland won the Football League championship and reached the semi-final of the FA Cup.

Sunderland retained the championship in 1892-93 and were runners-up to Aston Villa in the 1893-94 season. Sunderland were also champions in 1894-95. Ted Doig did not miss a Football League or FA Cup game between 20th September 1890 and 9th September 1895. Doig, who always wore a cap to hide his baldness, won back his place as Scotland's goalkeeper. During his time at Sunderland he played 417 games for the club.

In the 1896-97 season William Foulke of Sheffield United caused a stir in a game against Aston Villa when he bounced the ball as far as the halfway line. This was within the rules at the time, but as players were able to barge into other players when they had the ball, goalkeepers saw that tactic as very risky. However, Foulke, who was 6ft 2ins tall and weighed over 16 stone at the time, he was fairly confident that he would be able to regain possession of the ball.

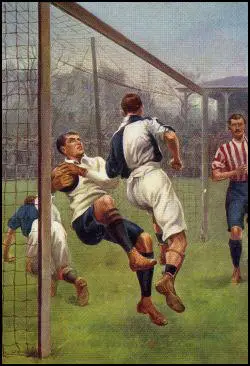

The shoulder charge remained an important part of the game. This could be used against players even if they did not have the ball. If a goalkeeper caught the ball, he could be barged over the line. As a result, goalkeepers tended to punch the ball a great deal. In 1894 the Football Association introduced a new law which stated that a goalkeeper could only be charged when playing the ball or obstructing an opponent.

This new law was not popular with the outfield players. Ernest Needham, who played for England and Sheffield United remarked: "The last part of Rule 10 says, 'The goalkeeper shall not be charged except when he is holding the ball, or obstructing an opponent'; and it is seldom, and not for long, that the custodian is in contact with the ball. It is safe to say that the goalkeeper is the best protected man on the field."

In September, 1898, the South Essex Gazette reported that in a game against Brentford, two West Ham United players, George Gresham and Sam Hay, "bundled the goalkeeper into the net whilst he had the ball in his hands". The goal stood because this action was within the rules at the time.

goal line in a game in 1904.

One man who was unlikely to be barged over the line was William Foulke. A very large man he was nicknamed "Fatty" or "Colossus" by the fans. He once said: "I don't mind what they call me as long as they don't call me late for my lunch." C. B. Fry, the famous cricketer, who also played football for Southampton, remarked: "Foulke is no small part of a mountain. You cannot bundle him."

One journalist wrote that: "His ponderous girth brings no inconvenience and the manner in which he gets down to low shots explodes any idea that a superfluity of flesh is a handicap." Foulke grew increasingly heavy and by 1903 he was over 20 stone. At that time the shoulder charge remained an important part of the game. This could be used against players even if they did not have the ball. If a goalkeeper caught the ball, he could be barged over the line. This was a problem that was rarely encountered by Foulke.

Sheffield United, led by Ernest Needham, won the First Division championship in the 1897-1898 season. William Foulke only missed one game and the team had the best defensive record in the league and one journalist described Foulke as the "greatest goalkeeper in the world". In a game against Liverpool in November, 1898, George Allan tried to intimidate Foulke. The Liverpool Post reported that "Allan charged Foulke in the goalmouth, and the big man, losing his temper, seized him by the leg and turned him upside down."

Foulke could kick the ball the length of the field and it was said that he could punch the ball as far as some players could kick it. According to one contemporary account, Foulke could punch "the ball well over the half-way line." He was also described as "a leviathan at 22 stone with the agility of a bantam".

William Foulke won his first international cap against Wales on 29th March 1897. Although England won 4-0, surprisingly, it was the only time he played for his country. At that time John Robinson was the regular England goalkeeper. Foulke was known to be unpopular with the Football Association. As the Sheffield Daily Telegraph pointed out: "It is a pity that Foulke cannot curb the habit of pulling down the crossbar, which on Saturday ended in his breaking it in two. On form, he is well in the running for international honours, but the Selection Committee are sure to prefer a man who plays the game to one who unnecessarily violates the spirit of the rules."

William Foulke also played for Chelsea before moving to Bradford City. He now weighed over 25 stone and was no longer as agile as he was and he was forced to retire from first-class football.

Harry Hampton joined Aston Villa in April 1904. He had a great first season scoring 22 goals in 28 games. He also scored both goals in Aston Villa's FA Cup Final victory over Newcastle United. He maintained this good form over the next ten years.

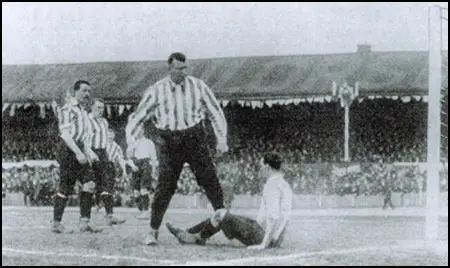

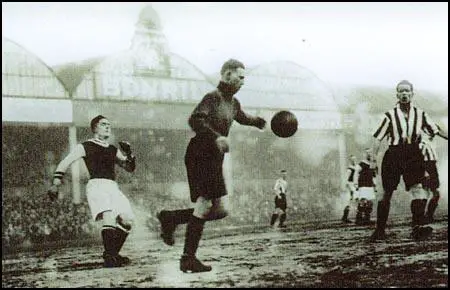

Even goalkeepers of the size of William Foulke was vulnerable to being barged over the line by aggressive forwards. Harry Hampton of Aston Villa scored several goals in this way. Tony Matthews described Hampton in his book, Who's Who of Aston Villa as: "Afraid of no one, his strong, forceful, determined and appreciated by plenty. The idol of the Villa Park faithful, Hampton was robust in the extreme. He often barged the goalkeeper, including the hefty 22 st. body-weight of Fatty Foulke, and the ball (if he had it in his possession) into the back of the net, sometimes taking a co-defender along for good measure with one almighty shoulder-charge."

Law 8 of the Football Association stated: "The goalkeeper may, within his own half of the field of play, use his hands, but shall not carry the ball." Leigh Roose, who began playing for Aberystwyth Townin the North Wales Combination League, in 1894, developed a strategy that was within the law but greatly increased the effectiveness of the goalkeeper. Roose began to bounce the ball up to the half-way line before launching an attack with a long kick or a good throw. As Spencer Vignes points out in his book on Roose: "This was perfectly within the letter of the law, though few goalkeepers risked doing it for fear of either leaving their goal unattended or being streamrollered by a centre-forward. It became a highly effective, direct way of launching attacks and Leigh used it to his side's advantage whenever possible."

Leigh Roose, who went on to play for Stoke City, Everton, Sunderland, Celtic, Huddersfield Town, Aston Villa and Arsenal, influenced a whole generation of goalkeepers. For example, Tommy Moore, who played for West Ham United, between 1898 to 1901, often moved up field and started an attack by punching the ball into the opposition half. In a game against Chesham, the game was so one-sided that Moore spent most of the game on the offensive. As the local newspaper reported: "Moore had so little to do that he often left his goal unprotected and played up with the forwards."

Another outstanding goalkeeper was Jack Hillman. As Mike Jackman pointed out in The Legends of Burnley, Hillman was "one of the great exponents of goalkeeping during the Victorian period." Hillman's form was so good that he was selected to play for England against Northern Ireland on 18th February 1899. England won 13-2.

However, Burnley struggled in the First Division of the Football League. Unless the team beat Nottingham Forest on the final day of the season, they would be relegated. Burnley lost 4-0. After the game, the Nottingham Forest captain, Archie McPherson, claimed that Hillman had tried to bribe his team to lose the game. Hillman was called to appear before the Football Association. The FA refused to believe Hillman's claim that he was only joking and he was banned from football for 12 months. He not only lost a year's wages but a £300 benefit.

Sam Hardy won his first international cap for England on 16th February 1907. He was England's regular goalkeeper for the next 13 years. Jesse Pennington, the England full-back, claimed that Hardy was "one of the greatest goalkeepers I ever saw play." Charlie Buchan went further: "Hardy, I consider the finest goalkeeper I played against. By uncanny anticipation and wonderful positional sense he seemed to act like a magnet to the ball. I never saw him dive full length to make a save. He advanced a yard or two and so narrowed the shooting angle that forwards usually sent the ball straight at him."

Most experts consider Leigh Roose, who played for Wales, was the best goalkeeper of this period. Frederick Wall, the Secretary of the Football Association described Roose as "a sensation... a clever man who had what is sometimes described as the eccentricity of genius. His daring was seen in the goal, where he was often taking risks and emerging triumphant." Rouse was an entertainer, who carried out pranks to get laughs. This included sitting on the crossbar at half-time.

The Bristol Times reported that: "Few men exhibit their personality so vividly in their play as L. R. Roose.... He rarely stands listlessly by the goalpost even when the ball is at the other end of the enclosure, but is ever following the play keenly and closely. Directly his charge is threatened, he is on the move. He thinks nothing of dashing out 10 or 15 yards, even when his backs have as good a chance of clearing as he makes for himself. He will also rush along the touchline, field the ball and get in a kick too, to keep the game going briskly."

Leigh Roose played like a modern "sweeper" and spent much of his time outside his penalty area. He later wrote about this strategy: "A goalkeeper should take in the position (of the opposing players) at once and... if deemed necessary, come out of his goal immediately. He must be regardless of personal consequences and, if necessary, go head first into a pack into which many men would hesitate to insert a foot, and take the consequent greulling like a Spartan." He added that "the reason why goalkeepers don't come out of the goal more often is their regard for personal consequences." Roose pointed out a good goalkeeper should not "keep goal on the usual stereotype lines... and is at liberty to cultivate originally". According to Roose: "players with the intelligence to devise a new move or system, and application to carry it out, will go far."

In his roundup of the 1901-02 season, the football journalist, James Catton, described Leigh Roose in Athletic News as "the Prince of Goalkeepers". This was a term that had previously been used to describe Teddy Doig. Roose in fact replaced Doig as Sunderland's goalkeeper in 1908. Leigh Roose soon become a strong favourite with the Sunderland fans. They liked the way he set up attacks by running out to the half-way line. Roose told a journalist that he was surprised that not more goalkeepers did not follow his example: "The law states that any (goalkeeper) is free to run over half of the field of play before ridding themselves of the ball. This not only helps to puzzle the attacking forwards, but to build the foundations for swift, incisive counter-attacking play. Why then do so few make use of it?"

George Holley, who played for Sunderland with Roose later explained why this strategy was not followed by many other goalkeepers. "He was the only one who did it because he was the only one who could kick or throw a ball that accurately over long distances, giving himself time to return to his goal without fear of conceding."

Several clubs complained to the Football Association about Roose's strategy. Several committee members felt that Roose was ruining the game as a spectacle by his ability to break up creative and attacking play. However, they could not agree about what to do about it.

In June 1912 the Football Association finally decided to change Law 8 that stated: "The goalkeeper may, within his own half of the field of play, use his hands, but shall not carry the ball." It now read: "The goalkeeper may, within his own penalty area, use his hands, but shall not carry the ball." In other words, if a goalkeeper wanted to move around his penalty area while handling the ball, he had to bounce rather than carry it as he went. He was also not allowed to handle the ball outside the penalty area.

On 5th September, 1931, Celtic played Rangers in front of an 80,000 crowd at Ibrox Stadium in Glasgow. Early in the second half Sam English raced through the Celtic defence and looked certain to score, when Celtic's international goalkeeper, John Thomson dived at his feet. Thomson's head collided with English's knee and he was taken unconscious from the field. According to The Scotsman, Thomson "was seen to rise on the stretcher and look towards the goal and the spot where the accident happened".

John Thomson was taken to the Victoria Infirmary but he had fractured his skull and he died at 9.25 that evening. He was 22 years old. Over 40,000 people attended the funeral in Cardenden, including thousands who had travelled through from Glasgow, many walking the 55 miles to the Fife village.

In 1934 Simon Raleigh of Gillingham died from a brain haemorrhage following a clash of heads with Brighton's Paul Mooney. The Brighton player was so distressed by Raleigh's death that he retired from playing football.

On 1st February 1936, Sunderland played Chelsea at Roker Park. According to newspaper reports it was a particularly ill-tempered game and Chelsea's Billy Mitchell, the Northern Ireland international wing-half, was sent off. The visiting forwards appeared to be targeting the Sunderland goalkeeper, Jimmy Thorpe, who took a terrible battering during the match.

Sunderland took a 3-1 lead but Chelsea fought back and Jimmy Bambrick, scored with a shot outside the area. A few minutes later, with Bambrick rushing in at full speed, Jimmy Thorpe misjudged a back-pass and allowed it to run over his arm. Bambrick continued his run and had an easy tap in to make it 3-3. One newspaper reported that "atrocious goalkeeping cost Sunderland a point".

The Sunderland Football Echo argued that: "Thorpe has shown some excellent goalkeeping this season, but he seldom satisfies me when the ball is crossed. On Saturday his failures had an entirely different origin, and I can come to no other conclusion than that the third goal to Chelsea was due to 'wind up' when he saw Bambrick running up." As the author Nick Hazlewood has pointed out in his book about goalkeepers, In the Way! Goalkeepers: A Breed Apart?: "Thorpe was scared said his critics; he'd turned chicken at the moment of truth."

As a result of the battering he had received, Jimmy Thorpe was admitted to the local Monkwearmouth and Southwick Hospital suffering from broken ribs and a badly bruised head. Thorpe had also suffered a recurrence of a diabetic condition that he had been treated for two years earlier. Thorpe died of diabetes mellitus and heart failure on 9th February, 1936. Thorpe, who was only 22 years old, left a wife and young son.

The following day, the Sunderland Football Echo journalist apologized for what he had written a few days earlier: "I know many who would give anything now to feel that they had not uttered the harsh words they spoke in the heat of the moment regarding Jimmy Thorpe's failure to prevent the two Chelsea goals in the second half last week. They did not know that the man whose failures were cursed was actually a hero to carry on at all. Neither did I know, and I confess now that I myself would give anything to have been in the position to have known and never to have given pen to what I wrote. I do not think he was able to read them and if this is so I am glad that his last days were not saddened by anything I had written because I know he was sensitive about his job."

Sunderland won the First Division league title that season and Thorpe's championship medal was presented to his widow.

As a result of Thorpe's death, the Football Association decided to change the rules in order to give goalkeepers more protection from forwards. Players were no longer allowed to raise their foot to a goalkeeper when he had control of the ball in his arms.

Primary Sources

(1) Mike Jackman, Blackburn Rovers : An Illustrated History (1995)

John Gow was plucked from the Scottish club Renton. His debut, against Sunderland on 11 October 1890, proved a lively affair, with the Scottish custodian involved in a sharp piece of practice. With the game drifting to a close, and the Rovers holding a lead of 3-2, a Sunderland player stuck a shot at the Blackburn goal. Realising that the ball was out of his reach Gow immediately tugged at the crossbar to ensure that the ball sailed narrowly over. Understandably, the Sunderland players were vociferous in their claims that a goal should be awarded and that the ball had passed under the bar. With no netting to make things easier the referee had a difficult choice to make. However, Mr Duxbury was up with the play and ruled that the ball wound have struck the crossbar and therefore ignored the Sunderland claims for a goal, thus enabling the Rovers to hang on for a win.

(2) Archie Hunter, Triumphs of the Football Field (1890)

The following week we had a runaway match with the Small Heath Swifts and established a record. Our opponents were a young team, but had entered bravely for the Birmingham and District Cup and it fell to their lot to encounter us first. Well, we were in very good trim and practically the Swifts could do nothing to oppose us. I don't know how many goals I kicked myself on this occasion, for I speedily lost all count. Probably I gained a dozen or so. Anyhow, at the end of the play the score stood - Villa 21 goals, and Small Heath Swifts none! It was at this match that a humourist fetched our goalkeeper a chair to sit down upon, as he had nothing to do. But Copley hated inaction and once, being tired of standing between the posts and never getting a chance of using his feet, he came up the centre of the field and as the ball was shot from our opponents' goal he struck it back again with his fist. I may add that from that return we scored. But then we could have scored from anything. It was a glorious day - for the winners. At half-time ten goals had been placed to our credit and in the second half we scored eleven.

(3) Scottish Sport (2nd January, 1895)

In Foulke, Sheffield United have a goalkeeper who will take a lot of beating. He is one of those lengthy individuals who can take a seat on the crossbar whenever he chooses, and shows little of the awkwardness usually characteristic of big men.

(4) Sheffield Daily Telegraph (15th February, 1897)

It is a pity that Foulke cannot curb the habit of pulling down the crossbar, which on Saturday ended in his breaking it in two. On form, he is well in the running for international honours, but the Selection Committee are sure to prefer a man who plays the game to one who unnecessarily violates the spirit of the rules.

(5) Liverpool Daily Post (29th November, 1898)

Allan charged Foulke in the goalmouth, and the big man, losing his temper, seized him by the leg and turned him upside down.

(6) C. B. Fry, Southern Echo (21st April, 1902)

The outstanding feature of the match was the grand goalkeeping of Foulke. he made a number of good saves, and on two or three occasions cleared the ball from what appeared impossible positions. Once, near the end, from a corner, he effected an absolute miracle with four or five men right on to him.

(7) Ernest Needham, Association Football (1901)

The popular idea that football is a dangerous game will surely have to undergo modification, but we must acknowledge that it was formerly dangerous. Once broken limbs from kicks, and broken ribs from charges, were quite every-day occurrences, and, to a great extent, men went on the field with their lives in their hands. It is safe to say that now there is no more risk in playing, even a fast game, than there is in any other active sport.

Surely last season's freedom from accident in First Division matches is sufficient evidence of this. I do not remember that any player had a limb broken, and even the Second Division was almost equally free. The object of many changes in the rules has been to extend protection to those engaged, and especially to the goalkeeper. Never now can we see two or three men rush at this isolated guard, while another pops the ball through. To begin with, it is difficult to get near enough to him for a charge without the "off-side rule" coming into operation. Then, again, the last part of Rule 10 says, "The goalkeeper shall not be charged except when he is holding the ball, or obstructing an opponent"; and it is seldom, and not for long, that the custodian is in contact with the ball. It is safe to say that the goalkeeper is the best protected man on the field.

(8) In an interview in the London Evening News in 1913, William Foulke described an incident with Larry Bell of Sheffield Wednesday in a game that took place in the 1897-98 season.

It was really all an accident. Just as I was reaching for a high ball Bell came at me, and the result of the collision was that we both tumbled down, but it was his bad luck to be underneath, and I could not prevent myself from falling with both knees in his back. When I saw his face I got about the worst shock I ever have had on the football field. He looked as if he was dead."

(9) Philip Gibbons, Association Football in Victorian England (2001)

Trinidad-born Wharton had been the Amateur Athletic Association's hundred yards champion in both 1886 and 1887, as well as one of the first black professional footballers in England. However, his first team appearances were limited owing to the arrival of Willie Foulke from the Blackwell club in Derbyshire.

Foulke, who stood six feet and two inches tall, with a natural weight of thirteen stone, dominated the United goal area well into the following century, when his weight exceeded twenty stone. He played a leading part in United's success of the late 1890s as well as appearing in the English national side.

(10) The Times (1906)

A goalkeeper and his methods of defence are the result of the physical makeup of the individual. He should stand about six foot and no nonsense. Size gives one the impression of strength and safety and enables a goalkeeper to deal with high and wide shots with comparative ease, where a smaller or shorter man would be handicapped. On the other hand, a tall and ponderous goalkeeper is at a disadvantage with the smaller and more agile rival when required to get down to swift ground or low shots.To the agility of youth should be coupled the sagacity of veterancy.

(11) The Daily Mail (1906)

Goalkeeping is not only a physical exercise but a moral discipline when looked upon in its true light and from a right and proper standpoint. It develops courage, perseverance, endurance and other qualities which fit one for fighting the battle of life. It is an education of body and mind.

(12) Spencer Vignes, The Remarkable Life and Death of Leigh Richmond Roose (2007)

His (Leigh Roose) style of play was also completely different from any other goalkeeper of the time. Here was someone prepared to take on menacing centre forwards at their own game, rushing out to break up opposing attacks by whatever means possible - diving on the ball, kicking it clear, or resorting to more brutal means, such as clattering into a player with his six-foot frame. Up until then, this just hadn't happened. Goalkeepers were supposed to stay on or at least near their goal line at all times, daring to venture out only on rare occasions. Not Leigh, who spent long periods of each match playing in the position known today as 'sweeper', tidying up every loose ball in the gap immediately behind his defenders.... As George Holley put it, "He was the mould from which the rest were created."

Leigh's reflexes were astonishing, and he could punch the heavy brown footballs used in Edwardian days further than many of his opponents were able to kick it. Then there was his very own secret weapon, bouncing the ball all the way up as far as the halfway line before punting it towards the opposition goal with one of his monstrous trademark kicks. This was perfectly within the letter of the law, though few goalkeepers risked doing it for fear of either leaving their goal unattended or being steamrollered by a centre forward. It became a highly effective, direct way of launching attacks and Leigh used it to his side's advantage whenever possible....

One aspect of the game that had remained constant over the years was Leigh's attack-minded style of goalkeeping, running out as far as the halfway line while in possession of the ball before releasing it with one giant kick or throw. Although other keepers had by now become more adventurous in their play, using the whole of the penalty area rather than staying routed to their line waiting for a shot, Leigh was still in a world of his own when it came to using an entire half.

(13) Thomas Richards, Man of Genius (1905)

I have always believed that Roose grew to his full height as a man in the purgatorial crisis of a penalty, drying off the clay around his feet, washing away the dross which entered his character with the gold... Arthur's sword against the bare fist. Then came the signal; the ball travelled like a bolt from the foot of the penalty taking forward, and in the blink of an eyelid, revolution, a thump, and the ball landed in the heather and gorse of the Buarth...

Last season when Stoke played Arsenal at Plumstead, I watched the Reds swoop down on Roose like a whirlwind. There was a scrimmage in goal and Roose was down on the ball like a shot with a heap of Arsenal and Stoke players on top of him. It was all Lombard Street to a penny orange that the Reds would score. Presently from out of the ruck emerged Roose clinging to the ball, which he promptly threw away up the field. I'll bet that the thrill of triumph which went through him was ample compensation for any hard knocks he received.

(14) Leigh Roose's article on goalkeeping first appeared in The Book of Football (1906)

A good goalkeeper, like a poet, is born, not made. Nature has all to do with the art in its perfection, yet very much call be done by early training, tuition and practice. A "natural" goalkeeper seems to keep his form without much effort. All the training possible will not make a man a goalkeeper. You must coach him, explain the finer points of the game to him, and show him the easiest and best way to take the ball to the greatest advantage, and how to meet this or that movement of the attacking forwards, and then he will be something more than a mere physical entity or specimen. Granted that the aspirant has the inherent and essential qualities in him to become successful, it is the early work and coaching that are the determining causes of after success, without which he can never hope to attain the ideal.

In the other positions in the field success is dependent upon combined effort and upon the dovetailing, of one player's work with another. With the goalkeeper it is a different matter entirely. He has to fill a position in which the principle is forced upon him that "it is good for a man to be alone" - a position which is distinctly personal and decidedly individualistic in character. His is the most onerous post, and one which is equally responsible. Any other player's mistakes may be readily excused, but a single slip on the part of the last line of defence may be classed among the list of the unpardonable sins - especially when the International Selection Committee is on business bent. His one mistake or lapse may prove more costly than a score of errors committed by all his fellow clubmates put together....

Everything that the aspirant to first-class rank attempts to accomplish should be marked by a steady, quiet confidence. There should be nothing, to denote the novice about his play, albeit a champion in embryo. As a rule, men are clever at a game because they are fond of it, and when a man is fond of anything in which he takes part, he does not usually or as a rule scamp such work as he participates in.

Players with intelligence to devise a new move or system, and application to carry it out, will go tar. And for that reason the possession of personal conception and execution is desirable, although a "player with an opinion" nowadays which is not in consonance with the stereotyped methods of finessing and working for openings is shunned to no small degree, as though lie carried about with him the germs of an infectious disease.

A goalkeeper, however, can be a law unto himself in the matter of his defence. He need not set out to keep goal on the usual stereotyped lines. He is at liberty to cultivate originality and, more often than not, if he has a variety of methods in his clearances and means of getting rid of the ball, he will confound and puzzle the attacking forwards....

A goalkeeper should be one possessed of acute observation and independent thought. He should be aggressive, and have the fighting instinct or spirit in him, and if in combination with a modicum of "temper" - so called - he will be none the worse for that. Temper is only a form of energy and, so long, as it is controlled, the more we have of it in a custodian the better. He should know every move of the game as well as he knows the alphabet, and study the mysteries of attack and the intricacies of defence, at the same time carrying his individual attitude with perfect balance. If he can give to his work the spice of a little originality, it will prove to be his advantage. Stale minds rather than stale bodies and muscles are responsible for many of the indifferent displays we read of. When a person's mannerisms seem part of the man, unconscious and necessary to the full self-expression of his work or play, it is folly to attempt to cramp one's methods for the sake of conformity to a general type. When, however, they are foreign to his role, they become a just source of irritation, and the reason for their adoption is possibly found in the fact that the person who has aped somebody's methods, which were in turn sub-aped by others, was suffering at both extremities of his person in that lie was the possessor of a swollen head and had grown too big for his boots.

The fairest judgement of a man is by the standard of his work, and the best goalkeeper is the one who makes the fewest mistakes. Perfect custodians are not in evidence in this mundane sphere. There certainly are degrees of comparison in the best of goalkeepers, albeit of a limited kind, as the tactics indulged in by keepers are merely matters of personal equation...

There is a speculative element in every goalkeeper's venture from under his posts. Leaving one's goal is looked upon as a cardinal sin by those armchair critics who tell a goalkeeper what he should do and what he should not do, and administer advice from the philosophic atmosphere of the grand stand. They wobble mentally, in proportion with the custodian's success or want of success in rushing out to meet an opponent even when the result is as inevitable as when a man's logic is pitted against a woman's tears. A goalkeeper should take in the position at once and at a glance and, if deemed necessary, come out of his goal immediately, even if things were not what they at first seemed. Never more than in this case is it true that he who hesitates is lost. He must be regardless of his personal consequences and, if necessary, go head first into a pack into which many men would hesitate to insert a foot, and take the consequent gruelling like a Spartan. I am convinced that the reason why goalkeepers don't come out of their goal more often is their regard for personal consequences. If a forward has to be met and charged down, do not hesitate to charge with all your might. If you rush out with the intention of kicking, don't draw back but Kick (with a capital K!) at once.

If a thing is worth doing at all, it is worth doing properly and with all one's energy, and he who gives hard knocks must be prepared to accept hard knocks in return. A goalkeeper should believe in himself. If you don't have the confidence, it is a moral certainty your backs cannot, and their play will show it by lying close to goal and doing most of your work. As a consequence of this, the half-backs have too much defence thrown upon them, and are thus hampered, and cannot feed their forwards, so that there is a weak display all round which takes its origin from the defects of one man, and a want of confidence in the last defensive unit on the side.

Consistency should be aimed at. A goalkeeper on whom you cannot rely or depend is like a man to whom you ask an inconvenient question, and who prevaricates in his answer. He should not be one of those who "keep" one day with extreme brilliance, and another day make repeated and egregious mistakes. His work should be notable for its uniformity and in distinct contrast to the curate's egg, which was found to be good only in parts...

If a player has the ability to keep goal, he should set about trying to improve his style. He may possibly be a little unfinished at first, but he is bound to improve if he combines with the agility of youth a matured observation of the game which time alone can give. A sure eye, a perfect sense of time, and a heart - even as big as a hyacinth farm - are necessary to a goalkeeper's art, for it is an art of the rarest type. He should be as light on his feet as a dancing master, yet nothing is more reprehensible in a goalkeeper than taking wild, flying kicks, or using his feet in any way when he can use his hands, as there is safety in numbers and two hands are better than one foot. When he does kick, his kicking should be accuracy itself, so as to land the ball exactly where he intends. There must be boot behind the ball, muscle behind the boot, the intelligence behind both. He should be as cool as the proverbial cucumber, and good temper is an essential. Excitability and an uncontrollable disposition or temper are antagonistic to good judgement, and the goalkeeper who is devoid of judgement is useless for all practical purposes.

If a player is mapping out a goalkeeper's career for himself, his course should be one of moderation, regularity, and simplicity. Nothing is ever achieved without effort or even sacrifice in one's pastimes, as in the higher walks of life, and only a study of its points and experience will educate him up to the standard expected of him. Let a player take that for granted, and he will succeed.

(15) Vanessa Tomlin, curator of the Mitchell and Kenyon Collection, gave an interview in 2006 about the value of the film we have of Leigh Roose keeping goal for Wales against Ireland in March, 1906.

In terms of its historical significance the film is absolutely priceless, being the earliest surviving footage of an international football match that we know of. What has survived is in such perfect condition that it looks as though it was filmed yesterday. It contains all the elements we associate with more advanced football coverage such as the teams running out on to the pitch, the action and the reaction of the crowd. We think shots of weeping Geordies and Scousers at football matches is a relatively new thing. Mitchell and Kenyon's footage tells us it's not.

The only real disappointment is that Billy Meredith is missing from the action because he was suspended at the time and couldn't play. But Leigh Roose is there, captured for posterity. One thing you can really begin to appreciate by watching the film is how much danger goalkeepers were in at that time. Mitchell and Kenyon always liked to film corners being taken because they could almost guarantee where the action was about to take place. As a result they recorded many goalkeepers being physically battered by opposing players. It's hardly surprising that so many of them feared catching the ball, preferring instead to try and punch it clear.

(16) J. A. H. Catton, Athletic News (9th November, 1908)

Leigh Richmond Roose was a superman among men, and he alone stood between Blackburn and the honour they coveted. What would have happened to Sunderland in this encounter without such a guardian, I hesitate to think. Whether the shots were straight or oblique, high or low, hurtling like cannonballs or sneaking surprises, Roose was at the ready. Valiant though volatile, dextrous though daring, he stands forth as one of the most glorious goalkeepers of modern times.

(17) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

At the end of the season I was again chosen as England's centre-forward. The match was against Belgium at Brussels.

Soon after the game started, I noticed the Belgium goalkeeper always took three or four strides with the ball before making a clearance. So I awaited my opportunity and, as he was about to kick clear, I put my foot in front of the ball.

It rebounded quickly from the sole of my boot, flew hard up against the cross-bar and bounced clear. If the ball had gone into the net, I think there would have been a riot.

From that moment, the crowd roared every time I got the ball. You see, you are not supposed to go anywhere near a Continental goalkeeper even if he has the ball in his possession.

It is the same now on the Continent. Perhaps there is some excuse for them as the grounds are so hard over there that a goalkeeper is likely to be seriously hurt if he takes a tumble.

It brings back to mind another incident in Vienna with a Continental goalkeeper. He was an enormous chap, inches taller than I and weighing about 15 stone. I charged him when he had the ball in his arms. He went down like a log though the charge was shoulder to shoulder, nothing out of the ordinary.

Almost at once, a stretcher-bearer party appeared and carried him off. A substitute took his place before the game restarted. I came to the conclusion afterwards that the goalkeeper was not really hurt-he wasn't, actually-but that the Viennese wanted a better goalkeeper in his place.

Needless to say, I was not very popular after that charge. I thought there would be trouble before the game was over. There was.

Nearing the end, our right half-back tackled an Austrian, who had the ball at his feet. He, too, went down apparently hurt. The crowd broke on to the field and the game finished abruptly. The crowd were demonstrative but, I am glad to say, not too pugnacious.

Now, with the British Associations back in the F.I.F.A., something may be done about the law relating to charging goalkeepers on the Continent. Our F.A. have had a booklet printed in various languages illustrating the law as it stands, and it has been distributed widely abroad but I fear that our interpretation will never be favourably received outside the British Isles.

There must be a ruling that will be carried out wherever soccer is played, a compromise that will be acceptable both to us and to those abroad. I suggest that it should be on the lines of allowing the goalkeeper undisputed possession in his own six-yard goal area. But it will be a long time before that comes into force.

There is another defensive point that worries me too. It is the sliding tackle which is so prevalent nowadays and which, instead of being a last means of defence, is one of the main tricks in a defender's repertoire.

In my opinion, this tackle which I first saw introduced by Dicky Downs, the sturdy Barnsley miner who afterwards went to Everton, has done more than anything else, except the change in the offside law in 1925, to alter the character of the game.

It is because of this tackle, which of course, comes within the laws, that the game has speeded up so much and consequently lost some of its accuracy. A player cannot pass a ball correctly if he has to do it hurriedly.

It also puts an end to many promising movements. A defender sliding along the ground for a few yards, sometimes from behind, puts the ball into touch or out of play and what might have been a spectacular movement, is brought to a sudden end.

And when a forward is in front of goal, he always has the fear that he will be tackled from behind. So he shoots hurriedly and often wide of the mark.

It brings more injuries to players, too. Coming unexpectedly as it must do, it jars the ankles and the knees of the unfortunate victim. Sooner or later, the player is hurt. Cartilage operations, more or less unknown in the early years of the century, are now commonplace.

Soccer in the old days was tougher and one got more hard shakings from charges and strong tackles but serious injuries were fewer then than they are now. Once you were free of an opponent, there was little fear he would bring you down from behind.

In fact, it was something of a "cold war" in those far-off days. Players tried to frighten you off your game but their bark was much worse than their bite.

I remember one game in Lancashire. As soon as the game started, the left-back came across to me and said: "If you come any of your tricks today, I'll kick you over the grandstand." The left half-back who was standing near, overheard the remark and added: "Yes, and I'll go round the other side and kick you back on the field again."

Yet during the game nothing unusual happened. They played the game fairly and, though they were beaten, never carried out anything like the threats. Sometimes, though, these tactics came off.

There were exceptions, but you soon got to know them. To be warned is to be forearmed and the clever player, without changing his style to any great extent, steered clear of the danger.

But in those days one had a little time, after beating an opponent, to study the next move. As there was no danger from the rear, he could place the ball where he wanted it. Movements of four or five passes were carried out successfully. You do not see them often in these hectic days, mainly because one of the players is brought down by a sliding tackle.Half-backs like Peter McWilliam, Scotland and Newcastle United, or Charlie Roberts of Manchester United and England, would never have dreamed of using this method. They relied upon clever positioning and timely interventions.

(18) Nick Hazlewood, In the Way! Goalkeepers: A Breed Apart? (1996)

More than 80,000 were at Ibrox to witness an event that has remained imprinted on the Scottish football psyche ever since. With the second half barely five minutes old, Rangers striker Sam English broke free and lined up to shoot from near the penalty spot. He seemed certain to score, when Thomson launched one of his do-or-die head-first saves at the attacker's feet. It was Thomson's trademark save - in February 1930 against Airdrie he'd been injured doing exactly the same thing, fracturing his jaw and injuring his ribs. This time there was an even more sickening crunch, Thomson's head colliding with English's knee at the moment of greatest impact. It was no longer a do-or-die moment, it was a do-and-die. The ball ran out of play, English fell to the ground and rose limping, Thomson lay unconscious, blood seeping into the pitch.

The dazed English was the first to realise the seriousness of the blow and hobbled over to the unmoving keeper, waving urgently for assistance. Celtic fans were cheering the missed goal, Rangers fans were taunting the injured keeper, but the gravity of the situation was soon upon them. Rangers' captain Davie Meiklejohn raised his arms to implore the home fans to be silent. A hush descended over the ground. In the stands Margaret Finlay, Thomson's fiancee, broke down as she saw him borne from the ground, head wrapped in bandages, body limp...

What followed was an outpouring of public grief that, it is said, briefly united communities across the sectarian divide. In Bridgeton, Glasgow, traffic was brought to a halt by thousands of pedestrians walking past a floral tribute to Thomson, placed in a shop window by the local Rangers supporters club. And at Glasgow's Trinity Congregational Church there were unruly scenes when thousands struggled to get into Thomson's memorial service. Women screamed with alarm at the crush and only swift action by police cleared a passageway and stemmed the rush. Celtic right-half Peter Wilson, who was due to read a lesson, failed to gain entrance and found himself stranded outside the church for the ceremony.

Tens of thousands went to Queen Street station to see the coffin off on its train journey home to Fife. Many thousands more made the same journey: by train, by car and by foot. Unemployed workers walked the 55 miles, spending the night on the Craigs, a group of hills behind Auchterderran. In Fife, local pits closed down for the day and it seemed as if the whole of Scotland had swelled the small streets of Cardenden. Thomson's coffin, topped by one of his international caps and a wreath in the design of an empty goal, was carried by six Celtic players the mile from his home to Bowhill cemetery, where he was laid to rest in the sad and quiet graveyard populated by the victims of many, many mining disasters.

(19) Willie Maley, quoted in James Hanley's, The Story of the Celtic: 1888-1938 (1960)

Among the galaxy of talented goalkeepers whom Celtic have had, the late lamented John Thomson was the greatest. A Fifeshire friend recommended him to the Club. We watched him play. We were impressed so much that we signed him when he was still in his teens. That was in 1926. Next year he became our regular goalkeeper, and was soon regarded as one of the finest goalkeepers in the country.

But, alas, his career was to be short. In September, 1931, playing against Rangers at Ibrox Park, he met with a fatal accident. Yet he had played long enough to gain the highest honours football had to give. A most likeable lad, modest and unassuming, he was popular wherever he went.

His merit as a goalkeeper shone superbly in his play. Never was there a keeper who caught and held the fastest shots with such grace and ease. In all he did there was the balance and beauty of movement wonderful to watch. Among the great Celts who have passed over, he has an honoured place.

(20) Sunderland: The Official History (1999)

Following our 3 - 3 draw with Chelsea on 1st February, one of the dailies reported that "Atrocious goalkeeping cost Sunderland a point". The goalkeeping referred to was that of James Thorpe; four days later, he died, baring sustained injuries to both his ribs and his face, the latter resulting in a very swollen eye. In a rough game that saw Chelsea's right half Mitchell being given his marching orders, Thorpe had sustained serious injuries that brought his life to an untimely end. At the subsequent inquest it was revealed that Jimmy suffered from diabetes and took insulin regularly He had fallen into a diabetic coma and the official cause of death was given as both diabetes mellitus and heart failure.

(21) Nick Hazlewood, In the Way! Goalkeepers: A Breed Apart? (1996)

In February 1936 Chelsea visited Sunderland and treated them to a brutal afternoon's entertainment in front of 20,000 spectators. It was also an afternoon that witnessed one of the quickest bits of backtracking since Napoleon hit snow in Russia.

Sunderland had been winning 3-1, but in an ill-tempered and poorly controlled game Chelsea pulled back to share the spoils. Police protection was needed to ensure the safety of the referee, and local journalists had no doubt who was to blame - Jimmy Thorpe, the Sunderland keeper. At 3-1 Thorpe had misjudged a ball and failed to clear it from his line and then, two minutes later, worried by the Chelsea striker Bambrick who was haring in, he had taken his eyes off the ball when running to collect a back-pass and allowed it to run over his arm, giving Bambrick his second easy goal in as many minutes...

Thorpe was scared said his critics; he'd turned chicken at the moment of truth. Little did they know that within 48 hours he would be dead. Knocked about on the pitch on the Saturday, Thorpe had suffered a recurrence of a diabetic condition that he had been treated for two years earlier, and which had lain dormant in his body ever since. He died in Monkwearmouth and Southwich Hospital at 2 p.m. on Wednesday afternoon. According to the newspapers there was not the slightest doubt that his death was due to blows received during the match.

(22) Sunderland Football Echo (6th February, 1936)

I know many who would give anything now to feel that they had not uttered the harsh words they spoke in the heat of the moment regarding Jimmy Thorpe's failure to prevent the two Chelsea goals in the second half last week. They did not know that the man whose failures were cursed was actually a hero to carry on at all. Neither did I know, and I confess now that I myself would give anything to have been in the position to have known and never to have given pen to what I wrote.