John Thomson

John Thomson was born in in Kirkcaldy, Scotland on 28th January, 1909. He grew up in the mining community of Cardenden in Fife. His father worked as a miner at the Bowhill Colliery. His parents, John and Jean Thomson, were members of the Protestant sect, the Church of Christ.

John was educated at Denend Primary School and Auchterderran Higher Grade School. He was a talented goalkeeper and was a member of the Auchterderran team that won the Lochgelly Times Cup. His teacher, N. E. Lawton, later pointed out: "He was very keen on football, and was always training and hitting away at a punch ball. He was a born goalkeeper."

At the age of fourteen he became an oncost worker at Bowhill Colliery. Thomson worked about 300 yards below the pithead surface and it was his job to uncouple the chain clips of the waggons that carried the coal that was brought up from the seams of the mine.

in the 1924-25 season Thomson played for Bowhill Rovers. The following season he joined Wellesley Juniors. The local newspaper, Fife Free Press, reported that the club "had unearthed a champion goalkeeper in Thomson... he is a youngster yet, but should develop." The Celtic manager, Willie Maley, sent his chief scout, Steve Callaghan, to take a look at this talented sixteen year old. After playing against Denbeath Star on 30th October 1926, Thomson was signed by the club for £10. As Thompson was taking part in the General Strike, it was a great time to become a professional footballer. His mother, Jean Thomson was opposed to the move as she considered football as a highly dangerous sport.

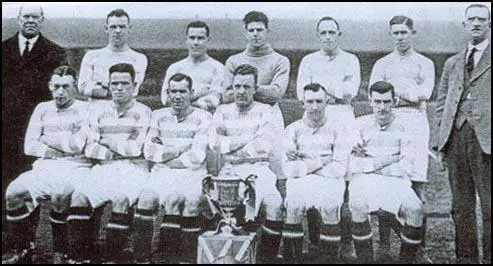

On 5th February, 1927, Celtic beat Brechin 6-3. Willie Maley was concerned by the way that his first choice goalkeeper, Peter Shevlin had let in three soft goals. Maley decided to give Thompson, who had just turned 18, a chance in the first team, in the next game against Dundee. He retained his place in the side and helped Celtic to finish in second-place to Rangers in the First Division of the Scottish League that year. He also won a Scottish Cup medal in 1927 when Celtic beat East Fife 3-1.

Several people mentioned that Thomson did not look like a goalkeeper. He was only 5 feet 9 inches tall and had small hands. Although teammate, Jimmy McGrory, called them "artist's hands". A friend, James Boyle, commented that he had "a slim and wiry body, but if he turned sideways, you could hardly see him." Thomson's biographer, Tom Greig, wrote in My Search for Celtic's John: "Thomson had smallish hands with strong, slender fingers.... Thomson also possessed a vice-like strength in powerful wrists and forearms. The combination of these physical attributes was the basis for his extraordinary shot-saving and clutching capabilities."

After playing in the away game against Rangers, Scotland's leading football journalist wrote: "I have no reason to change the opinion I first formed of young Thomson, the Celtic goalkeeper. Barring accident, he will one day play for his country." whereas Waverley of the Daily Record commented: "The Wellesley boy's anticipation was great throughout. His dealing with particularly heavy stuff from Cunningham and Archibald was masterful. He undoubtedly saved Celtic in the early stages. Thomson is a great goalkeeper." The following week Waverley also wrote about the performance of Thomson: "To Thomson, Parkland's eighteen-year-old goalkeeper, falls the honour and distinction of being the star performer in the latest Rangers-Celtic struggle. And this for the second week in succession. The Celtic keeper was simply immense. All sorts and conditions of shots came at Thomson. Point-blank range, low shots caught in a vice, running out to kick clear and clutch crosses again and again."

Several people mentioned that Thomson did not look like a goalkeeper. He was only 5 feet 8 inches tall and had small hands. Although teammate, Jimmy McGrory, called them "artist's hands". A friend, James Boyle, commented that he had "a slim and wiry body, but if he turned sideways, you could hardly see him." Johnny Thomson had smallish hands with strong, slender fingers, and I don't remember ever seeing an action photograph of him wearing gloves, even to cope with the heavy, often sodden balls of his day.... Thomson also possessed a vice-like strength in powerful wrists and forearms. The combination of these physical attributes was the basis for his extraordinary shot-saving and clutching capabilities.

On 5th February, 1930, was seriously injured in a game against Airdrieonians. He broke his jaw, fractured several ribs, damaged his collar bone, and lost two teeth. According to Tom Greig, the author of My Search for Celtic's John, his friend Jim Ferguson, asked John Thomson: "What was in his mind when he made the breakneck, goal-saving dives for which he was renowned. Thomson responded that he thought of nothing but keeping his eye on the ball, and if the ball was there to be won, he had to go for it." Once again Jean Thomson attempted to persuade her son to retire from the game. She said that she had a premonition that he would be killed playing football.

Thomson won his first international cap on 25th October, 1930. Scotland drew 1-1 with Wales. During the match Tom Bamford of Wrexham became the only man to score against Thomson in a full international. The following season he played for his country against Northern Ireland. Thomson kept a clean sheet and was chosen for the big game against England on 28th March, 1931. Despite Dixie Dean being in the English team Thomson stopped them from scoring in Scotland's 2-0 victory.

On 11th April 1931, 105,000 spectators watched Celtic played Motherwell in the final of the Scottish Cup at Hampden Park. The first game was drawn 2-2. Celtic won the replay 4-2 and so Thomson won his second cup winners medal.

James Hanley, wrote in the The Story of the Celtic: 1888-1938 (1960) that: "It is hard for those who did not know him to appreciate the power of the spell he cast on all who watched him regularly in action. In like manner, a generation that did not see John Thomson has missed a touch of greatness in sport, for which he was a brilliant virtuoso, as Gigli was and Menuhin is. One artiste employs the voice as his instrument, another the violin or cello. For Thomson it was a handful of leather."

Desmond White, the chairman of Celtic, claimed Thomson was the best goalkeeper he had ever seen. He added: "Johnny had the ability to rise in the air high above the opposition. It was this almost ballet-like ability and agility which, in his tremendous displays, endeared him to the hearts of all Celtic supporters." Dr. James Hadley remarked: "The generation that saw John Thomson in action will agree it would be hard to exaggerate his magical skill and will acknowledge that neither before nor since have they seen a goalkeeper so swift, so elegant, so superbly safe in operation. He had the spring of a jaguar and the effortless grace of a skimming swallow."

The Celtic manager, Willie Maley, commented: "His merit as a goalkeeper shone superbly in his play. Never was there a keeper who caught and held the fastest shots with such grace and ease. In all he did there was the balance and beauty of movement wonderful to watch." It was rumoured that Arsenal in the First Division of the Football League was interested in signing him.

In 1931 Thomson got engaged to Margaret Finlay and starting making plans for opening a gents' outfitters in Glasgow. Unlike most of his teammates Thomson was not a Roman Catholic. In fact he was a member of the Church of Christ, a small Protestant evangelical church. Thomson once complained to Celtic striker Jimmy McGrory that an opposing centre-forward kept calling him a "papish bastard". McGrory replied that he was called one every week. Thomson retorted: "That's all right for you, you are one!"

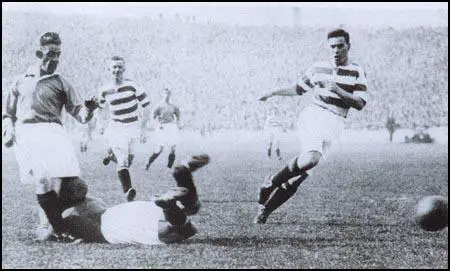

On 5th September, 1931, Celtic played Rangers in front of an 80,000 crowd at Ibrox Stadium in Glasgow. Early in the second half Sam English raced through the Celtic defence and looked certain to score, when Thomson dived at his feet. Thomson's head collided with English's knee which ruptured an artery in his right temple. One source (Celtic's Saddest Day) said "there were gasps in the main stand, a single piercing scream being heard from a horrified young woman." This was Margaret Finlay who was watching the game with Jim Thomson, John's brother.

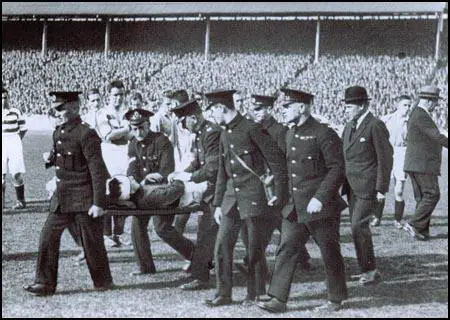

After receiving treatment from the St Andrew's Ambulance Association he was taken from the field on a stretcher. According to The Scotsman, Thomson "was seen to rise on the stretcher and look towards the goal and the spot where the accident happened".

Thomson was taken to the Victoria Infirmary. He had sustained a lacerated wound over the right parietal bones of the skull. This caused a depression of the skull, two inches in diameter. At 5 pm Thomson suffered a major convulsion. Dr. Norman Davidson carried out an emergency operation in an attempt to relieve the pressure caused by swelling in the injured brain. The operation was unsuccessful and John Thomson died at 9.25 that evening. He was 22 years old.

The journalist John Arlott wrote: "A great player who came to the game as a boy and left it still a boy; he had no predecessor, no successor. He was unique." The Celtic manager, Willie Maley, commented: " His merit as a goalkeeper shone superbly in his play. Never was there a keeper who caught and held the fastest shots with such grace and ease. In all he did there was the balance and beauty of movement wonderful to watch. Among the great Celts who have passed over, he has an honoured place.

An estimated 30,000 people attended the funeral in Cardenden on Wednesday, 9th September, 1931. This including thousands who had travelled through from Glasgow, many walking the 55 miles to the Fife village. An estimated 20,000 turned out at Glasgow's Queen Street station in order to watch two trains set off with two thousand passengers who could afford to pay the four shillings return fare.

The official enquiry later found that the collision was an accident, and cleared Sam English of any blame. However, he was always jeered by Scottish crowds during future games. English retired from football in May 1938. He told a friend that since the accident that killed John Thomson he had "seven years of joyless sport".

Primary Sources

(1) N. E. Lawton, interviewed by the Lochgelly Times (September, 1931 )

He showed promise of great things even then (when he was at school). He was a fine lad, and even at school was a hero amongst the boys. He had a taking way with him, and his lead was always followed. He was very keen on football, and was always training and hitting away at a punch ball. He was a born goalkeeper. At school he showed his complete lack of fear which has characterised his career.

(2) Waverley, Daily Record (October 1927)

To Thomson, Parkland's eighteen-year-old goalkeeper, falls the honour and distinction of being the star performer in the latest Rangers-Celtic struggle. And this for the second week in succession. The Celtic keeper was simply immense. All sorts and conditions of shots came at Thomson. Point-blank range, low shots caught in a vice, running out to kick clear and clutch crosses again and again.

(3) Tom Greig, My Search for Celtic's John (2003)

Johnny Thomson had smallish hands with strong, slender fingers, and I don't remember ever seeing an action photograph of him wearing gloves, even to cope with the heavy, often sodden balls of his day.... Thomson also possessed a vice-like strength in powerful wrists and forearms. The combination of these physical attributes was the basis for his extraordinary shot-saving and clutching capabilities.

(4) James Hanley, The Story of the Celtic: 1888-1938 (1960)

It is hard for those who did not know him to appreciate the power of the spell he cast on all who watched him regularly in action. In like manner, a generation that did not see John Thomson has missed a touch of greatness in sport, for which he was a brilliant virtuoso, as Gigli was and Menuhin is. One artiste employs the voice as his instrument, another the violin or cello. For Thomson it was a handful of leather. We shall not look upon his like again.

(5) Nick Hazlewood, In the Way! Goalkeepers: A Breed Apart? (1996)

More than 80,000 were at Ibrox to witness an event that has remained imprinted on the Scottish football psyche ever since. With the second half barely five minutes old, Rangers striker Sam English broke free and lined up to shoot from near the penalty spot. He seemed certain to score, when Thomson launched one of his do-or-die head-first saves at the attacker's feet. It was Thomson's trademark save - in February 1930 against Airdrie he'd been injured doing exactly the same thing, fracturing his jaw and injuring his ribs. This time there was an even more sickening crunch, Thomson's head colliding with English's knee at the moment of greatest impact. It was no longer a do-or-die moment, it was a do-and-die. The ball ran out of play, English fell to the ground and rose limping, Thomson lay unconscious, blood seeping into the pitch.

The dazed English was the first to realise the seriousness of the blow and hobbled over to the unmoving keeper, waving urgently for assistance. Celtic fans were cheering the missed goal, Rangers fans were taunting the injured keeper, but the gravity of the situation was soon upon them. Rangers' captain Davie Meiklejohn raised his arms to implore the home fans to be silent. A hush descended over the ground. In the stands Margaret Finlay, Thomson's fiancee, broke down as she saw him borne from the ground, head wrapped in bandages, body limp...

What followed was an outpouring of public grief that, it is said, briefly united communities across the sectarian divide. In Bridgeton, Glasgow, traffic was brought to a halt by thousands of pedestrians walking past a floral tribute to Thomson, placed in a shop window by the local Rangers supporters club. And at Glasgow's Trinity Congregational Church there were unruly scenes when thousands struggled to get into Thomson's memorial service. Women screamed with alarm at the crush and only swift action by police cleared a passageway and stemmed the rush. Celtic right-half Peter Wilson, who was due to read a lesson, failed to gain entrance and found himself stranded outside the church for the ceremony.

Tens of thousands went to Queen Street station to see the coffin off on its train journey home to Fife. Many thousands more made the same journey: by train, by car and by foot. Unemployed workers walked the 55 miles, spending the night on the Craigs, a group of hills behind Auchterderran. In Fife, local pits closed down for the day and it seemed as if the whole of Scotland had swelled the small streets of Cardenden. Thomson's coffin, topped by one of his international caps and a wreath in the design of an empty goal, was carried by six Celtic players the mile from his home to Bowhill cemetery, where he was laid to rest in the sad and quiet graveyard populated by the victims of many, many mining disasters.

(6) Tom Greig, My Search for Celtic's John (2003)

A Celtic attack had broken down. Davie Meiklejohn, the Rangers captain and right half, emerged with the ball and saw possibilities for an attack down Celtic's left flank, along the grandstand touchline. His measured pass was picked up by his team mate, the fleet-footed Jimmy Fleming, who was alert and quick enough to elude a challenging tackle from Celtic's left back Peter McGonagle. Looking up, Fleming immediately noted that the failed Celtic attack had caught their centre half Jimmy McStay upfield, and struggling to get back into the heart of his defence. He saw too that, unmarked, Rangers' young centre forward, Sam English, had stolen through the inside right channel into a dangerous position at the edge of Celtic's eighteen-yard box. The pass, which Fleming dispatched in front of the on-rushing English, was an inch-perfect invitation to shoot for goal, and English gave it his very best.

From the moment he had seen his team's forward momentum falter, Thomson was primed for danger. He could see that his captain McStay would not make it back in time. He tensed as the thrusting counter-attack developed with such speed in front of him. He had watched McGonagle's tackle on Fleming fail. Now English was rapidly bearing down on him. No other defender was close enough to intervene. All his senses told the keeper that English was going to shoot. In the few seconds that remained to him to make a decision, Thomson was torn between two of his most basic goalkeeping instincts formed long before on the far-off fields of his native Fife: not to leave his line, unless in extremis; but always to go for the ball. He moved towards English, crouching and creeping forward to narrow the angle. Fractionally he hesitated on the six yard line, winding himself up to pounce. All the options to save his goal had now come down to his own judgment and personal courage. With eyes never leaving the ball, he launched himself towards his opponent's feet. As a contemporary photograph clearly shows, English's boot had already connected cleanly with the ball sending it goalwards before Thomson's brave and selfless dive had diverted it off his projectile body to trickle safely past his right hand post. The fact that the referee awarded a goal kick notwithstanding, Celtic's last line of defence had executed one of his bravest saves and once more had not been found wanting when crisis threatened his team.

But the drama was only beginning. The unstoppable momentum of Thomson's downward dive had carried him on into a fearful collision with the opposing centre forward. His cloth cap was pushed to the back of his head as it crashed into the inside of Sam English's left knee. Dreadful damage was inflicted to Thomson's right temple, leaving him prone and unconscious on the lbrox turf.

(7) The Celtic Handbook: 1932-33 (1933)

John Thomson as a goalkeeper stood out in splendid isolation. Peerless among goalkeepers and still in the morning of his career. He had attained heights never before scaled by goalkeepers of experience and greatness. His memory and his services are remembered and cherished. Amongst the great Celts who have gone, he has a place - an honoured place."

(8) Willie Maley, quoted in James Hanley's, The Story of the Celtic: 1888-1938 (1960)

Among the galaxy of talented goalkeepers whom Celtic have had, the late lamented John Thomson was the greatest. A Fifeshire friend recommended him to the Club. We watched him play. We were impressed so much that we signed him when he was still in his teens. That was in 1926. Next year he became our regular goalkeeper, and was soon regarded as one of the finest goalkeepers in the country.

But, alas, his career was to be short. In September, 1931, playing against Rangers at Ibrox Park, he met with a fatal accident. Yet he had played long enough to gain the highest honours football had to give. A most likeable lad, modest and unassuming, he was popular wherever he went.

His merit as a goalkeeper shone superbly in his play. Never was there a keeper who caught and held the fastest shots with such grace and ease. In all he did there was the balance and beauty of movement wonderful to watch. Among the great Celts who have passed over, he has an honoured place.