Conscription and the Second World War

On 27th April 1939, Neville Chamberlain made the controversial decision to introduce conscription, although repeated pledges had been given by him against such a step. It is claimed that Leslie Hore-Belisha, Secretary of State for War, had forced Chamberlain to change his mind. Both members of the Labour Party and the Liberal Party objected to the measure and according to Winston Churchill because of "the ancient and deep-rooted prejudice which has always existed in England against Compulsory Military Service." (1)

Clement Attlee argued: "Whilst prepared to take all necessary steps to provide for the safety of the nation and the fulfillment of its international obligations, this House regrets that His Majesty's Government in breach of their pledges should abandon the voluntary principle which has not failed to provide the man-power needed for defence, and is of opinion that the measure proposed is ill-conceived, and, so far from adding materially to the effective defence of the country, will promote division and discourage the national effort, and is further evidence that the Government's conduct of affairs throughout these critical times does not merit the confidence of the country or this House." (2)

Attlee later attempted to explain why he opposed conscription. He thought this was of doubtful military value and that military conscription might pave the way for industrial conscription. He admitted to Mark Arnold-Forster: "But you must remember the hangover from the last war. The generals were given far too many men. They sacrificed men because they wouldn't use their brains. Didn't happen in the second war." (3)

Parliament passed the Military Training Act by 380 to 143 votes. This introduced conscription for men aged 20 and 21, who were now required to undertake six months' full-time military training. Once this decision had been taken, however, the Labour Party quickly accepted it, and it soon ceased to be contentious. A resolution at the Labour Party Conference calling for non-cooperation in defence measures was defeated by a huge majority - 1,670,000 to 286,000. Attlee and the shadow cabinet continued to oppose any further concessions to Adolf Hitler. (4)

Parliament also passed legislation that protected some important occupations from national service. After consulting with business leaders, the government published the Schedule of Reserved Occupations. Employers were also able to ask for individual key workers employed in one of these occupations not to be conscripted into the armed forces. In January 1939, a handbook sent to every household in the country, which catalogued the various full-time and part-time war jobs. It was designed to check impulsive volunteering by skilled workers and to help others to find the appropriate service. Over the next few months more than 200,000 men had been granted deferment at their employers' request. By the summer of 1939 over 300,000 had volunteered for the armed forces and around 500,000 recruits for the Civil Defence services. (5)

Young men who were not wearing the uniform of the armed forces because they were working in reserved occupations, sometimes came under pressure from the local population: "Matt, my boyfriend, was exempted from call-up for a while because he was needed at home. He worked at Devonport Dockyard building ships. It got embarrassing when people in our village started to whisper: Why isn't he fighting like our men?" (6)

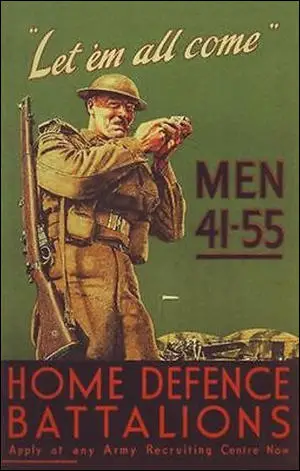

On the outbreak of the Second World War,the regular army and its reserves numbered about 400,000, and there was a roughly equal number of territorials. On the first day of war, Parliament passed the National Service (Armed Forces) Act, under which all men between 18 and 41 were made liable for conscription. The registration of all men in each age group in turn began on 21st October for those aged 20 to 23. The following May, registration had extended only as far as men aged twenty-seven. Richard Titmuss said that the "call-up" seemed "to progress with the speed of an elephant trying to compete in the Derby". (7)

To others the pace was going too fast. Frank Edwards, a 33-year-old, a businessman from Birmingham, wrote in December, 1939: "I think there were some surprised people today when the 22-year-olds were called up, owing to this being sooner than was expected, especially as it was authoritatively stated after the last call up on 21st October that it was not expected the next age group would be called on until the new year." (8)

Muriel Simkin was on honeymoon when war was declared. Soon after she arrived home her husband, John Simkin, and her brother, Jack Hughes, received their call up papers. "We were on our honeymoon when war was declared. We had planned to have a fortnight's holiday but we had to come home after a week. It was not a very good start to our married life... People on the whole were more friendly during the war than they are today - happier even. People helped you out. You had to have a sense of humour. You couldn't get through it without that." (9)

Provision was made in the legislation for people to object to military service. Not only on pacifist grounds, which had been accepted in the First World War, but also on political grounds. Of the first batch of men aged 20 to 23, an estimated 22 in every 1,000 objected and went before local conscientious objection tribunals. The tribunals varied greatly in their attitudes towards conscientious objection to military service, and the proportions of conscientious applications totally rejected ranged from 2 per cent in London to 27 per cent in south-west Scotland. The longer the war continued, the lower the percentage objected to conscription. By the summer of 1940 only 16 in every thousand did so." (10)

The political and moral views of the tribunal chairman were vitally important. It was difficult always to get a fair hearing in London, especially during the Blitz. On one occasion the chairman told the applicant that his request was rejected because "Even God is not a pacifist, for he kills us all in the end". A man could himself apply for postponement of his call-up on grounds of severe personal hardship. Over the whole war more than 200,000 such applications were accepted, and a sizable proportion of the applicants had their postponement renewed." (11)

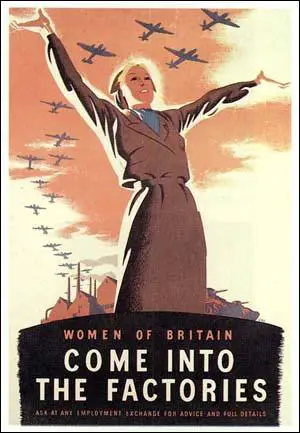

Just before the start of the war the government established Women's Auxiliary Territorial Service to compensate for those men conscripted into the armed forces. During the war women served as office, mess and telephone orderlies, drivers, postal workers, butchers, bakers, and ammunition inspectors. However, by 1941 the country remained short of workers in vital industries. Ernest Bevin, the Minister of Labour, made a speech where he asked for 100,000 women to volunteer their services: "I have to tell the women that I cannot offer them a delightful life. They will have to suffer some inconveniences. But I want them to come forward in the spirit of determination to help us through." (12)

By the end of the year Winston Churchill, decided that the government would have to introduce legislation to make sure they had enough women's labour: "Should the Cabinet decide in favour of compelling women to join the Auxiliary Services, it is for consideration whether the method employed should not be by individual selection, rather than by calling up by age groups. The latter system would inevitably discourage women from joining up until their age group was called.... The campaign for directing women into the munitions industries should be pressed forward. The existing powers should be used with greater intensity." (13)

The following month, on 18th December 1941, the National Service Act was passed by Parliament. Men were now required to do some form of National Service up to the age of 60, which included military service for those under 51. The main reason was that there were not enough men volunteering for police and civilian defence work. This legislation also called up unmarried women and all childless widows aged between twenty and thirty. They were allowed a choice between the auxiliary services and important jobs in industry. Since the beginning of the war young women had been reluctant to join the women's services, which had a bad reputation for impropriety. One young women wrote: "I can lay my hand on my heart and say truthfully that I have not yet met a woman in the twenties who is not in an awful state about conscription." (14)

Eventually married women were made liable to be directed into war-related civilian work, although pregnant women and mothers with young children were completely exempt. Muriel Simkin worked in a munitions factory in Dagenham. This was very dangerous work: "We had to wait until the second alarm before we were allowed to go to the shelter. The first bell was a warning they were coming. The second was when they were overhead. They did not want any time wasted. The planes might have gone straight past and the factory would have stopped for nothing. Sometimes the Germans would drop their bombs before the second bell went. On one occasion a bomb hit the factory before we were given permission to go to the shelter. The paint department went up. I saw several people flying through the air and I just ran home. I was suffering from shock. I was suspended for six weeks without pay. They would have been saved if they had been allowed to go after the first alarm. It was a terrible job but we had no option. We all had to do war work. We were risking our lives in the same way as the soldiers were." (15)

Joyce Storey went to work at the Magna Products at Warmley, near Bristol, a big engineering firm with huge wartime contracts. "My first impression of this great all male domain was not a good one, and the dust, grit and grime mingled with a strong smell of oil, along with all the lathes and machinery, awed and scared me. Because of the shortage of men, women were coming into the foundries and into the Works.... When the sirens sounded, it was works policy to leave the factory and file quickly into the shelters. One day, a bomb made a direct hit on one of the shelters at the Filton Aerodrome works, killing all the people inside. Later that day, all the other employees at Filton had been sent home because of the tragedy. They had arrived home white and shaken, none of them being able coherently to tell the story, and wondering how their friends and workmates could ever be properly buried. The shelters at Filton were never re-opened, but were sealed over and became a tomb." (16)

By the summer of 1941 almost 2,500,000 men were in the British Army and by the end of the war it had risen to 2,920,000. During the war 144,079 British soldiers were killed, 239,575 were wounded and 152,079 were taken prisoner. The Royal Air Force reached a total strength of 1,208,843 men and women. A total of 70,253 RAF personnel were lost on operations. The Royal Navy lost 9.3 per cent of its personnel in action during the war, the highest proportion among the British services. (16)

Primary Sources

(1) Winston Churchill, memorandum (6th November, 1941)

It may be a convenience to my colleagues if I set out the provisional views which I have formed on some of the major issues which we have to settle.

(1) The age of compulsory military service for men should be raised by ten years, to include all men under 51. While this might not make very many men available for an active fighting role, it would assist the Minister of Labour in finding men for non-combatant duties in the Services.

The possibility that the age should be raised again later on need not be excluded; but it would seem that an increase of ten years in the upper limit would be sufficient at the moment.

(2) The case for calling up young men at eighteen and a half, instead of nineteen, seems fully established. Indeed, I would go further and call them up at eighteen if this would make any substantial contribution.

(3) On the whole, I am not yet satisfied, in view of the marked dislike of the process by their Service menfolk, that a case has been established for conscripting women to join the Auxiliary Services at the present time. Voluntary recruitment for these Services should however be strongly encouraged.

(4) Should the Cabinet decide in favour of compelling women to join the Auxiliary Services, it is for consideration whether the method employed should not be by individual selection, rather than by calling up by age groups. The latter system would inevitably discourage women from joining up until their age group was called.

(5) The campaign for directing women into the munitions industries should be pressed forward. The existing powers should be used with greater intensity.

(6) Employers might well be encouraged, in suitable cases, to make further use of the services of married women in industry. This would often have to be on a part-time basis, and means must be found to ease the burden on women who are prepared to perform a dual role.

(2) Ethel Robinson lived in Liverpool during the Second World War. She was interviewed by Jonathan Croall, for his book, Don't You Know There's a War On? (1989)

My husband had wanted to go in the navy, but he had spondylitis in the spine, which is a form of arthritis, so they wouldn't take him in. He was shattered really, because he'd set his heart on getting into the navy. Which they found he had spondylitis, they couldn't give him any treatment, so he had to just pet on with it. He had to give the pub up and go and work on the docks, repairing ships. It was horrible, he'd never done anything like that in his life, you see, and it nearly killed him. He had to climb rigging and climb over ships' sides and things like that. Then, after the children were born, he had to go and work in the Royal Ordnance factory, making guns on shift work, and he hated that as well. But he wouldn't go on the disabled list, not with the sort of jobs they offered you then. So he stuck it out actually.

Although he couldn't go to the war, he'd get a lot of women saying, "Why aren't you fighting for us? My husband's out fighting for you." Well, you just don't bother to answer; and these were the same women who were carrying on with all kinds. This was the abuse they used to get, men that were working during the war, a lot of abuse from women and other men.

(3) Joyce Storey, Joyce's War (1992)

I went to work at the Magna Products at Warmley, a big engineering firm with huge wartime contracts. My first impression of this great all male domain was not a good one, and the dust, grit and grime mingled with a strong smell of oil, along with all the lathes and machinery, awed and scared me. Because of the shortage of men, women were coming into the foundries and into the Works. There were women conductors on the buses taking over until the men came home again, though, at the end of the war, they were not so keen to let go of their new independence. The end of this war brought many unheard and undreamt of changes.

When the sirens sounded, it was works policy to leave the factory and file quickly into the shelters. One day, a bomb made a direct hit on one of the shelters at the Filton Aerodrome works, killing all the people inside. Later that day, all the other employees at Filton had been sent home because of the tragedy. They had arrived home white and shaken, none of them being able coherently to tell the story, and wondering how their friends and workmates could ever be properly buried. The shelters at Filton were never re-opened, but were sealed over and became a tomb.

After that, we were not so inclined to use the shelters at our works but would get right away from the place and run into the fields instead. Some of the men would make a bee-line for the pubs if they were open, but I enjoyed fresh air and the break from the dusty atmosphere of the machine shop. It cleared my head so that I was more alert when I returned.