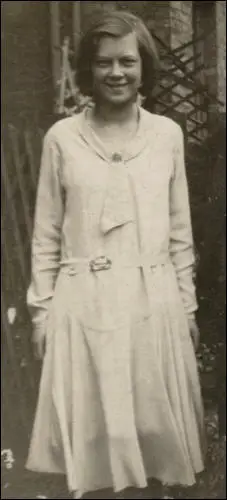

Muriel Simkin

Muriel Millicent Hughes, the first of three children, was born at No.2 Halidon Street, Hackney, London, on 29th July 1914. Her mother, Elizabeth Kershaw Hughes, was only nineteen, whereas her father, Thomas Griffiths Hughes, was thirty-four. Elizabeth, second eldest of thirteen children, was a "lady's maid" in the employment of the famous actress Sybil Thorndike and Thomas was a commercial traveller in the drapery trade.

Muriel claimed that her first memory of life was seeing her mother and her best friend and cousin, Elizabeth "Nellie" Stubbs, helping her father get ready to take part in the First World War. They were putting on his puttees that covered the lower part of the leg from the ankle to the knee. Puttees consisted of a long narrow piece of cloth wound tightly, and spirally round the leg, that was supposed to provide both support and protection. Mum remembers a great deal of laughter and her dad saying, "why are you in such a hurry, what do you plan to do while I'm away?"

As the war ended in 1918 and she must have been three or four at the time but she insists she remembers this event in great detail. Conscription began on 2nd March 1916, and originally specified that single men between the ages of 18 and 41 were liable to be called-up for military service unless they were widowed with children or ministers of religion. The Military Service Act was extended to married men on 25th May 1916. Given his age and marriage status I suspect the date was late 1917 or early 1918. Mum says he joined the Royal Medical Corp and did not see any action. Stella says the reason for this was he was kept in quarantine because he was a diphtheria carrier (someone whose cultures are positive for the diphtheria species but does not exhibit signs and symptoms).symptoms).

Elizabeth and Thomas Hughes (sitting in the middle of the picture) in a photograph

taken in 1922. Tom Hughes, Muriel's father, holds his son, two-year-old John Hughes.

The girl sitting at the extreme right of the picture is Muriel's cousin Charlotte.

Another relative, Violet, sits between Muriel and her mother.

On his return my grandmother had two more children, Jack Hughes in 1920 and Stella Hughes in 1926. Stella is still alive and at the age of 94 she has provided me with important information on my mum and dad. When she was five or six, my mum began attending the Rams Episcopal Infant School in Hackney and she finished her education in 1928 at the Hackney Free & Parochial School.

Muriel and Stella both claim that their parents were very strict. Thomas Hughes was a commercial traveller and although he went to work in a suit and tie, he had very little money. Stella said that every morning before work he would place two old pence on the table to pay for food for the family. However, if there was a knock on the door, he would always put on his suit jacket before answering it. Stella said that both her mum and dad were fanatical about table-manners. For example, elbows on the table were strictly forbidden.

Muriel passed an examination that would have allowed her to stay on at school, but family finances meant that she had to leave at the age of fourteen. Even in old age she had lovely handwriting and had a good memory for spelling. I always considered her as an intelligent woman. Not in an academic sense (her mother had told her that girls should not read books) but she had good insight into people's characters. In current psychological terms, she had emotional intelligence. Her interest in other people made her popular with friends and family. However, she never made demands on people, and some people exploited this character trait.

Muriel Hughes, then aged about fourteen, is the young girl in the white dress sitting

at the rear of the charabanc with her family. my grandmother, sits propped up to the

right of her daughter. My grandfather is seated right at the back of the charabanc

flanked by Muriel's two siblings, Stella, aged two and her eight year old brother Jack.

Muriel's first job at the age of fourteen was at Barlow's Metal Box Factory in Hackney's Urswick Road. On her first day at the factory, Mrs. Hughes insisted that Muriel wear her "Velour" school hat to work. The headgear had been purchased for school wear, but "as the hat had cost money, she had to make use of it". As she left the house wearing the hated school hat, Muriel was told by her mother to look after the hat as it was "expensive". On her first day at work, the hat was blown off her head by a gust of wind and went under the wheels of a lorry.

Barlow's Metal Box Factory was close to her home but soon afterwards the family moved to Lea Bridge Road in Leyton and she continued to work at the Metal Box Factory. Muriel worked from 8 am to 6pm, making the hour's journey to the factory on foot to save the penny which could have been spent on the tram fare. This included a three mile walk across the Hackney Marshes. This is one of the largest areas of common land in London, with 136.01 hectares (336.1 acres) of protected commons.

In 1928, Muriel earned 5s 6d a week at the Metal Box factory. She later recalled how after a week's labour, she kept one shilling for herself and handed over the remaining 4s 6d to Mrs. Hughes for "housekeeping". In 1932, Muriel secured employment with the large tailoring firm of Horne Brothers, a company which made men's suits and trousers at premises in South Hackney.

In 1932, aged 18, she had her first romantic relationship. Tom Heath worked at Horne Brothers and was 26 years old. They only went out a couple of times and she insisted that their evening out always ended up with a handshake. Another problem was that while living with her parents she had to arrive home by 10.00 p.m. The relationship came to an end when a workmate informed her that he was married.

Muriel's uncle, Joe Hughes lived in a flat in Garnham Street, Stoke Newington. In 1935 he moved to a flat in Ilford. The family who moved into the flat in Garnham Street, was Jane Simkin, who was now known as Jane White, and her three children, John (21), William (20) and their half-sister, Lily White (15). They were having trouble with their radio aerial and my mum was asked by her uncle to go round to show them how it had to be positioned.

Both of Mrs White's sons showed an interest in Muriel. Bill wanted to ask her out, but John (known to all of his friends as Ted) told his mother, that he had just met "the girl he was going to marry". Bill was the first one to make a move, but it was Ted who successfully invited her to go out with him to see the film Mutiny on the Bounty, starring Charles Laughton and Clark Gable. As a result of the "10 o'clock rule" the missed the end of the main film (in those days cinemas showed two films at a time).

Stella was only nine-years-old when Ted took Muriel on their first date. Stella was anxious to see the new boyfriend and when he brought her back home she leant over the upstairs bannister rails. However, she could not see him as he was standing outside, but she could hear him singing a song to Muriel, Without a Word of Warning, a hit for Bing Crosby that first appeared in the film, Two for Tonight (1935).

Ted Simkin worked at the large Mac Fisheries depot at Finsbury Park in North London and spent time as a porter at the famous Billingsgate Fish Market before becoming a "fish salesman". Muriel talked fondly about the high-quality fish he was able to supply free of charge to the Hughes family. According to Muriel, during this period, Ted had a very outgoing personality, and with his accordion playing, he was a popular guest at parties.

Stella says that Ted was always telling jokes and was a very funny man. He was also a fanatical Spurs supporter and he often took her to White Hart Lane to see games. Muriel was not interested in football and did not go to games. Stella admitted she was not interested either but she took the opportunity to go out with Ted. However, she soon learnt to love the game and has been a life-long supporter of Spurs.

Ted had not known his father, John Edward Simkin, who had been killed on the Western Front in 1915 when he was only one year-old. He did not see much of his stepfather, Harry White, who left the family home when he was very young, According to Muriel it seems that an older colleague at work, Izzie Wright, became a father figure. In the early days of their relationship they went on outings to the countryside or the seaside with other couples, including Izzie and his wife Lilly, and Muriel's cousin Winnie Treweek and her new husband George Logsdon.

Muriel Hughes married John Simkin at West Hackney Church, Stoke Newington on 26th August 1939. They went away for two weeks at Weymouth. While on their honeymoon Neville Chamberlain announced that Britain was at war with Germany. She recalled: "We were on our honeymoon when war was declared. We had planned to have a fortnight's holiday, but we had to come home after a week. It was not a very good start to our married life."

John Simkin, was photographed Louis Edward Muller, a German immigrant.

Stella, her sister and Winnie, her future sister-in-law.

On their return they moved into their new council house in 98 Rogers Road, Dagenham, Essex. At the time of her marriage, Muriel was employed as an "Examiner and Finisher" at the London tailoring firm of Horne Brothers, earning 8s 6d a week. On the first day of the Second World War, Parliament passed the National Service (Armed Forces) Act, under which all men between 18 and 41 were made liable for conscription. The registration of all men in each age group in turn began on 21st October for those aged 20 to 23. Ted continued his work as a salesman at the fish market until he was conscripted into the Royal Artillery on 15th July 1940.

"I went with my parents to London to see off my husband and brother. They had both been called up by the army. After we left them at the railway station we got caught in an air-raid. We had to get off the bus after it caught fire. We ran for shelter. While we were running, I looked at my dad and he appeared to be on fire. I said: "Dad, you're alight." He nearly had a heart attack and I was not very popular when he discovered that I was mistaken and that it was only the torch in his pocket that had been accidentally turned on while he was running."

Young women without children were encouraged to do war work. Muriel joined the Briggs munitions factory in Dagenham. During the Blitz, these factories were a major target for the Luftwaffe. Mum's work was highly dangerous: "It was a terrible job, but we had no option. We all had to do war work... We had to wait until the second alarm before we were allowed to go to the shelter. The first bell was a warning they were coming. The second was when they were overhead. They did not want any time wasted. The planes might have gone straight past and the factory would have stopped for nothing."

These regulations made the work especially precarious. "Sometimes the Germans would drop their bombs before the second bell went. On one occasion a bomb hit the factory before we were given permission to go to the shelter. The paint department went up. I saw several people flying through the air and I just ran home. I was suffering from shock. I was suspended for six weeks without pay. They would have been saved if they had been allowed to go after the first alarm... We were risking our lives in the same way as the soldiers were."

On the outbreak of the war, Sir John Anderson, the Home Secretary and the Minister of Home Security, commissioned the engineer, William Patterson, to design a small and cheap shelter that could be erected in people's gardens. Within a few months nearly one and a half million of these Anderson Shelters were distributed to people living in areas expected to be bombed by the Luftwaffe. Anderson shelters were given free to poor people. Men who earned more than £5 a week could buy one for £7. The main problem was that under a quarter of the public had no gardens. Made from six curved sheets bolted together at the top, with steel plates at either end, and measuring 6ft 6in by 4ft 6in (1.95m by 1.35m) the shelter could accommodate six people. These shelters were half buried in the ground with earth heaped on top. The entrance was protected by a steel shield and an earthen blast wall.

Muriel had one of these shelters in her garden. "We had an Anderson shelter in the garden. You were supposed to go into the shelter every night. I used to take my knitting. I used to knit all night. I was too frightened to go to sleep. You got into the habit of not sleeping. I've never slept properly since. It was just a bunk bed. I did not bother to get undressed. It was cold and damp in the shelter. I was all on my own because my husband was in the army."

In 1940 Muriel and Ted had a lucky escape: "You would go nights and nights, and nothing happened. On one occasion when my husband was on leave, I think it was a weekend, we decided we would spend the night in bed instead of in the shelter. I heard the noise and woke up and I would see the sky. They had dropped a basket of incendiary bombs and we had got the lot. Luckily not one went off. Next morning the bombs were standing up in the garden as if they had grown in the night."

Muriel claimed that certain things improved during the war: "People on the whole were more friendly during the war than they are today - happier even. People helped you out. You had to have a sense of humour. You couldn't get through it without that. The worst part was having you husband and brothers away from you. We never heard from Jack, my brother, for five months. He couldn't communicate at all because he was involved in important battles in North Africa. It was very worrying. We knew a lot of his regiment had been killed. Then we saw his picture in the Daily Express newspaper. He was being inspected by General Montgomery. It was not until then that we knew he was alive."

in North Africa in 1942. Corporal Jack Hughes, Muriel Simkin's younger brother

stands on the far left of the row of soldiers.

Muriel Simkin managed to survive the bombing raids, but the extended family did suffer one major tragedy. "Rosie, my mum's sister, had to go to hospital to have a baby. Her mother-in-law looked after her three-year-old son. There was a bombing raid and Rosie's son and mother-in-law rushed to Bethnal Green underground station. Going down the stairs somebody fell. People panicked and Rosie's son was trampled to death."

After the death of John Edward Simkin in 1956, Muriel Simkin found work in a factory in Barking. Later she worked at the Electric Windings factory in Romford. Living in Harold Hill she continued working until breaking her leg at the age of 70. Muriel Simkin retired to Basildon but moved to Rayleigh after the death of her second husband, William Simkin, the brother of her former husband.

Muriel Simkin died in Southend Hospital on 10th February 2010.

Primary Sources

(1) The Second World War was declared when Muriel Simkin and her husband, John Simkin, were on their honeymoon.

We were on our honeymoon when war was declared. We had planned to have a fortnight's holiday but we had to come home after a week. It was not a very good start to our married life.

I went with my parents to London to see off my husband and brother. They had both been called up by the army. After we left them at the railway station we got caught in an air-raid. We had to get off the bus after it caught fire. We ran for shelter. While wee were running I looked at my dad and he appeared to be on fire. I said: "Dad, you're alight." He nearly had a heart attack and I was not very popular when he discovered that I was mistaken and that it was only the torch in his pocket that had been accidentally turned on while he was running.

(2) Muriel Simkin worked in a munitions factory in Dagenham during the Second World War.

We had to wait until the second alarm before we were allowed to go to the shelter. The first bell was a warning they were coming. The second was when they were overhead. They did not want any time wasted. The planes might have gone straight past and the factory would have stopped for nothing.

Sometimes the Germans would drop their bombs before the second bell went. On one occasion a bomb hit the factory before we were given permission to go to the shelter. The paint department went up. I saw several people flying through the air and I just ran home. I was suffering from shock. I was suspended for six weeks without pay.

They would have been saved if they had been allowed to go after the first alarm. It was a terrible job but we had no option. We all had to do war work. We were risking our lives in the same way as the soldiers were.

(3) While her husband was away in the army Muriel Simkin was forced to live on her own.

We had an Anderson shelter in the garden. You were supposed to go into the shelter every night. I used to take my knitting. I used to knit all night. I was too frightened to go to sleep. You got into the habit of not sleeping. I've never slept properly since. It was just a bunk bed. I did not bother to get undressed. It was cold and damp in the shelter. I was all on my own because my husband was in the army.

You would go nights and nights and nothing happened. On one occasion when my husband was on leave, I think it was a weekend, we decided we would spend the night in bed instead of in the shelter. I heard the noise and woke up and I would see the sky. They had dropped a basket of incendiary bombs and we had got the lot. Luckily not one went off. Next morning the bombs were standing up in the garden as if they had grown in the night.

Rosie, my mum's sister, had to go to hospital to have a baby. Her mother-in-law looked after her three-year-old son. There was a bombing raid and Rosie's son and mother-in-law rushed to Bethnal Green underground station. Going down the stairs somebody fell. People panicked and Rosie's son was trampled to death.

(4) Muriel Simkin admits that she enjoyed some aspects of the Second World War.

People on the whole were more friendly during the war than they are today - happier even. People helped you out. You had to have a sense of humour. You couldn't get through it without that.

The worst part was having you husband and brothers away from you. We never heard from Jack, my brother, for five months. He couldn't communicate at all because he was involved in important battles in North Africa. It was very worrying. We knew a lot of his regiment had been killed. Then we saw his picture in the Daily Express newspaper. He was being inspected by General Montgomery. It was not until then that we knew he was alive.