National Service Act

The British government introduced conscription in 1938. All men aged between 18 and 41 had to register with the government. Government officials then decided whether they should go into the army or do other war work. Most young men were recruited into the armed forces. This created a severe labour shortage and on 18th December 1941, the National Service Act was passed by Parliament. This legislation called up unmarried women aged between twenty and thirty. Later this was extended to married women, although pregnant women and mothers with young children were exempt from this work.

One vital need was for women to work in munitions factories. Other women were conscripted to work in tank and aircraft factories, civil defence, nursing, transport and other key occupations. This involved jobs such as driving trains and operating anti-aircraft guns, that had been traditionally seen as 'men's work'.

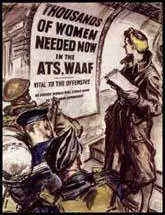

Cartoon in a British magazine in June 1943.

Primary Sources

(1) Ernest Bevin, the Minister of Labour, attempted to persuade women to volunteer for war work. A report of his speech was reported in the Manchester Guardian on 10th March, 1941.

Making an urgent appeal to women to come forward for war work mainly in shell-filling factories, Mr. Bevin said he did not want them to wait for registration to take effect. He wanted a big response now, especially by those who might not have been in employment before. There was a tendency to hang back and wait for instructions. If he could get the first 100,000 women to come forward in the next fortnight it would be priceless.

"I have to tell the women that I cannot offer them a delightful life, " said Mr. Bevin. "They will have to suffer some inconveniences. But I want them to come forward in the spirit of determination to help us through."

In districts where married women had been in the habit of doing the work the Government had decided to assist them so far as the minding of children was concerned. They had arranged for the rapid expansion through local authorities of day nurseries and they were asking local authorities to prepare immediately a register of "minders".

The married woman would pay only what she paid in pre-war days - about sixpence a day - and the Government would pay an additional sixpence a day for looking after the children.

(2) Muriel Simkin worked in a munitions factory in Dagenham during the Second World War. She was interviewed about her experiences for the book, Voices from the Past: The Blitz (1987).

We had to wait until the second alarm before we were allowed to go to the shelter. The first bell was a warning they were coming. The second was when they were overhead. They did not want any time wasted. The planes might have gone straight past and the factory would have stopped for nothing.

Sometimes the Germans would drop their bombs before the second bell went. On one occasion a bomb hit the factory before we were given permission to go to the shelter. The paint department went up. I saw several people flying through the air and I just ran home. I was suffering from shock. I was suspended for six weeks without pay.

They would have been saved if they had been allowed to go after the first alarm. It was a terrible job but we had no option. We all had to do war work. We were risking our lives in the same way as the soldiers were.

(3) Stella Hughes, interviewed in June, 2001.

I joined the Voluntary Nursing Service working from the Chingford post most evenings and at weekends in order to do my bit, so to speak, in the war. Five days a week I made soldiers uniforms working for Rego in Edmonton North London and then nursed at Whipps Cross Hospital in East London travelling there by bus. Along with my "indoor and outdoor" uniforms, which I was given I was issued a tin hat (which I had to pay for) but all this made me feel great.

(4) East Grinstead Courier (11th May, 1945)

The women in East Grinstead played a very important part in the life of the community. The Women's Voluntary Service was created at the beginning of the war and gave invaluable help in first-aid and nursing. Despite the fact that East Grinstead was not an industrial district it took an important part in the war by the manufacture of munitions and many women were engaged in the monotonous job for many years. They also replaced men who had joined the Forces, as skilled technicians, took part in the sale and delivery of food, postal work, railway work and service on the buses and other occupations connected with the war effort.

(5) Kay Ekevall lived in Edinburgh during the Second World War. As a result of the National Service Act she became a welder. She wrote about her war experiences in Jonathan Croall's book, Don't You Know There's A War On (1989)

Redpath's had never employed women before the war, as it was considered heavy industry. Women took part in most of the jobs, such as crane-driving, burning, buffing, painting, welding and such-like. I became a welder when there were both men and women trainees, but the men were paid more than the women. We had several battles over equal pay after we were used on the same jobs as the men, many of whom were as new to the skills as we were. By the end of my time we had managed to get close to the men's wage, but we only got equality in the case of the crane-drivers. On the whole the men didn't seem to resent the women, and the skilled men were friendly and helpful to the trainees. As it was an essential work industry, like the railways, I suppose they weren't afraid for their jobs. I believe there was some resentment in other factories at the dilution by cheap labour, and the unions campaigned for equal pay. But in heavy industry like Redpath's, no one thought women would be kept on after the war, so we were in a less vulnerable position. Spot welding in the electrical factories was the only kind of welding work that had been done by women up to then.