Wilf Copping

Wilfred (Wilf) Copping was born in Middlecliffe, near Barnsley, on 17th August 1909. He played Yorkshire junior football with Dearn Valley, Middlecliffe and Dartfield Rovers but after a trial with Barnsley F.C. in 1929 was rejected as someone not good enough for the Football League.

Copping did not give up and in 1930 was signed by Leeds United. Over the next three years, this hard-tackling left-half, played 159 games for the club.

A Leeds United historian has provided a good description of the player: "Wilf Copping was the original hard man of English football, paving the way for the likes of Norman Hunter, Ron Harris, Peter Storey, Tommy Smith and Graeme Souness in later decades. However, it is highly debatable whether any of them looked and played the part as well as Copping, with his boxer's nose and build, his unshaven appearance on match days and the bone shaking charges and tackles which were his trademark. Copping, at left half, was liable to unnerve the opposition with just one fixed stare from his craggy face. The harder the going, the more Copping liked it."

Copping's form was so good that he won his first international cap playing for England against Italy on 13th May 1933. The game ended in a 1-1 draw. Copping followed this with appearances against Switzerland (4-0 ), Northern Ireland (3-0), Wales (1-2), France (4-1) and Scotland (3-0).

In June 1934, George Allison, the manager of Arsenal, paid £8,000 for Copping. He joined a team that included players such as Alex James, David Jack, Cliff Bastin, Ted Drake, Joe Hulme, Eddie Hapgood, Ray Bowden, Frank Moss, Ray John, George Male and Jack Crayston.

In November, 1934, Copping played for England that played the world champions, Italy. Also in the England team that day was six other Arsenal players: Hapgood, Moss, Bowden, Drake, Bastin and Male. The game was really rough and according to Stanley Matthews: "The game got under way and from the very first tackles, I was left in no doubt that this was going to be a rough house of a game.... For the first quarter of an hour there might just as well have not been a ball on the pitch as far as the Italians were concerned. They were like men possessed, kicking anything and everything that moved bar the referee. The game degenerated into nothing short of a brawl and it disgusted me."

Eddie Hapgood later claimed that " Wilf Copping enjoyed himself that afternoon. For the first time in their lives the Italians were given a sample of real honest shoulder charging, and Wilf's famous double-footed tackle was causing them furiously to think." Stanley Matthews added: "Just before half-time, Wilf Copping hit the Italian captain Monti with a tackle that he seemed to launch from some where just north of Leeds. Monti went up in the air like a rocket and down like a bag of hammers and had to leave the field with a splintered bone in his foot."

Tom Whittaker pointed out in his autobiography, The Arsenal Story, that Copping became close friends with Jack Crayston "Although very dissimilar on and off the field, Crayston and Copping were inseparable. They trained together - that was another idea handed on by Chapman; he always insisted that a fast runner should train together with a slower mover, so as to help him increase his pace - and on all journeys were to be seen together, inevitably playing a peculiar form of Chinese whist."

In the 1934-35 season Copping was virtually ever present up until March 1935 when he hurst his knee in a match against Everton. That season Arsenal won the league championship by beating the runners-up, Sunderland, by four points.

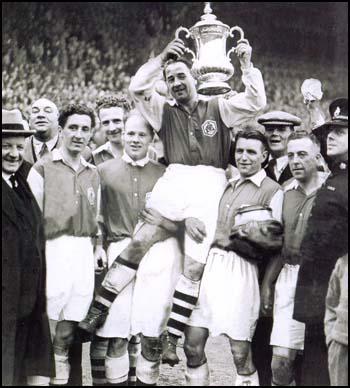

The 1935-36 season was not so good for Arsenal, finishing in 6th place behind Sunderland. However, Copping did play in the team that won the 1936 FA Cup Final against Sheffield United.

Copping was a member of the Arsenal team that won the championship in the 1937-38 season. He also retained his place in the England team playing against Norway (6-0), Sweden (4-0), Finland (8-0), Northern Ireland (5-1), Wales (2-1) and Czechoslovakia (5-4).

Copping also played in the game against Scotland on 9th April, 1938. In his autobiography, Bill Shankly, complained about one of Copping's tackles during the game. "Wilf Copping played for England that day, and he was a well-known hard man. The grass was short, the ground was quick, and I was playing the ball. The next thing I knew, Copping had done me down the front of my right leg. He had burst my stocking - the shin-pad was out - and cut my leg. That was after about ten minutes, and it was my first impression of Copping."

Bill Shankly, who played for Preston North End, was involved in another incident with Copping the following season. This time Copping injured Shankly's ankle. As Shankly later pointed out: "For years afterwards I played with my ankle bandaged and wore a gaiter over my right boot for extra support, and to this day my right ankle is bigger than my left because of what Copping did. My one regret is that he retired from the game before I had a chance to get my own back."

It is true that Wilf Copping had a reputation for hard-tackling and acquired the nickname "The Ironman". Copping once said: "The first man in a tackle never gets hurt." Bill Shankly claimed that Copping was a player who "played the man rather than the ball".

Tommy Lawton also complained about Copping. While playing for Everton in 1938 Lawton constantly beat the Arsenal defenders in the air and Copping warned him that he was "jumping too high" and that he would have to be "brought down to my level". As Lawton later recalled: "Sure enough the next time we both went for a cross, I end up on the ground with blood streaming from my nose. Wilf was looking down at me and he said 'Ah told thee, Tom. Tha's jumping too high!' My nose was broken. When Arsenal came to Everton, Copping broke my nose again! He was hard, Wilf. You always had something to remember him by when you played against him."

Jeff Harris argues in his book, Arsenal Who's Who (1995) that Copping "had the legendary reputation of being more than forceful in the tackle... and that he was the first to admit that he was temperamental and fiery his bone-jarring tackles were mainly timed to perfection and fair". Harris adds that proof that Copping was a clean player is the fact that he played in 340 league games and was never cautioned or sent-off during his career.

In March 1939, Copping asked Arsenal for a transfer. He told the manager that he felt "a war is coming and I want to get my wife and kids back up North before I join the army." Copping was allowed to rejoin Leeds United and during the Second World War he served in North Africa.

After the war Copping worked as a football coach for the Belgium national team, before spells with Southend, Bristol City and Coventry City (1956-59).

Wilf Copping died in Southend-on-Sea in June 1980.

Primary Sources

(1) Bill Shankly, Shankley (1977)

I was a hard player, but I played the ball, and if you play the ball you'll win the ball and you'll have the man too. But if you play the man, that's wrong. Wilf Copping played for England that day, and he was a well-known hard man. The grass was short, the ground was quick, and I was playing the ball. The next thing I knew, Copping had done me down the front of my right leg. He had burst my stocking - the shin-pad was out - and cut my leg. That was after about ten minutes, and it was my first impression of Copping. He was at left half and we came into contact in the middle of the field. I think the pitch was more responsible for what happened than anything, but I was surprised that he would do what he did to me in an international match. He was older than me and had a reputation. He didn't need to be playing at home to kick you -he would have kicked you in your own backyard or in your own chair. He had no fear at all. But while we were fighting for Scotland that day, we didn't go round trying to cripple people.

What Copping did stung me, but I didn't complain about him. I said to him, "Oh, you're making the game a little more important." Frank O'Donnell, who could look after himself, was annoyed at Copping and told him what he thought about it.

Copping had been after me and had caught me and I never contacted him again during the match. But he also hurt me when I played against him for Preston at Highbury on a Christmas Day. One of our players pulled out of a tackle for the ball and I had to go in to fight for it, and Copping caught me on my right ankle.

I was due to play another match the following day, but my ankle had blown up to an awful size. We went from London up to Fleetwood and Bill Scott said, "We'll have a try-out in the morning."

"What do you mean, a try-out?" I asked him, and I soon found out. Next morning my ankle was still badly swollen, and Bill got me a bigger boot to wear on my right foot. My normal size was six and a half, but I put on a size seven and a half or eight that day.

For years afterwards I played with my ankle bandaged and wore a gaiter over my right boot for extra support, and to this day my right ankle is bigger than my left because of what Copping did. My one regret is that he retired from the game before I had a chance to get my own back.

(2) Jeff Harris, Arsenal Who's Who (1995)

Although never cautioned or sent-off during his ten year career he (Wilf Copping) had the legendary reputation of being more than forceful in the tackle, this gave him the nickname of "The Ironman". Although Wilf was the first to admit that he was temperamental and fiery his bone-jarring tackles were mainly timed to perfection and fair. His famous quote was "The first man in a tackle never gets hurt". What added to his misconceived manner on the field was that he never shaved on match days, which gave him a mean blue stubble and more than a fearsome appearance.

(3) Tom Whittaker, The Arsenal Story (1957)

Mr. Allison followed the signing of Drake by securing Jack Crayston, that elegant gentleman of the football field, and the tough, blue-chinned Wilf Copping. Although very dissimilar on and off the field, Crayston and Copping were inseparable. They trained together - that was another idea handed on by Chapman; he always insisted that a fast runner should train together with a slower mover, so as to help him increase his pace - and on all journeys were to be seen together, inevitably playing a peculiar form of Chinese whist. These three players were to win two First Division championship medals and a Cup winners' medal in the few years left before the war stopped competitive football.

(4) Tommy Lawton, My Twenty Years of Soccer (1955)

It was during this tremendous Arsenal pressure that I went up for a high ball with Wilf Copping. Accidently he butted me in the face, and as our trainer was attending to me, Wilf came up and said, "You're jumping too high, Tom lad, I'll have to bring thee down to my level".

After the match it was found that my nose was broken... and would you believe it, when we met Arsenal in the return game later in the season, Wilf Copping and I had a similar collision with the same painful result for me-a broken nose. Obviously, Wilf Copping must have been my bogey man, but let me make this quite clear-both incidents were pure accidents, the sort of thing that could have happened to anyone.

(5) Stanley Matthews, The Way It Was (2000)

The game got under way and from the very first tackles, I was left in no doubt that this was going to be a rough house of a game. I wasn't wrong. After a challenge between Drake and Monti, the Italian had to leave the pitch with a broken foot after only two minutes. This only made matters worse. For the first quarter of an hour there might just as well have not been a ball on the pitch as far as the Italians were concerned. They were like men possessed, kicking anything and everything that moved bar the referee. The game degenerated into nothing short of a brawl and it disgusted me...

Ted Drake latched on to an ale-house long ball out of defence and broke away to score a wonderful individual goal on his international debut. He paid for it. Minutes after the game re-started I watched in sadness as Ted was carried from the field, tears in his eyes, his left sock torn apart to reveal a gushing wound.

I thought the three quick goals would calm the Italians down, showing them that rough-house play didn't pay dividends, but they got worse. I felt it was a great shame they had adopted such tactics because individually they were very talented players with terrific on-the-ball skills. They didn't have to resort to rough-house play to win games. Why they had done so this day was beyond me.

Not long after Eric Brook had put us two up, Bertolini hit Eddie Hapgood a savage blow in the face with his elbow as he walked past him. Eddie fell like a Wall Street price in 1929. The next few minutes were dreadful. Tempers flared on both sides, there was a lot of pushing and jostling and punches were exchanged. I abhor such behaviour on the field and when I saw Eddie Hapgood being led off with blood streaming down his face from a broken nose, it sickened me. I'd been really keyed up and looking forward to showing what I could do on the big international scene, but this game was turning into a nightmare.

The game got under way again and the Italians continued where they had left off. It got to a few of our players and I don't mind saying it affected me. Fortunately, we had two real hard nuts in the England side that day in Eric Brook and Wilf Copping who started to dish out as good as they got and more. Wilf was an iron man of a half-back, a Geordie who didn't shave for three days preceding a game because he felt it made him look mean and hard. It did and he was. Eric Brook received a nasty shoulder injury and continued to play manfully with his shoulder strapped up. He was in obvious pain but he just carried on, seemingly ignoring it.

Just before half-time, Wilf Copping hit the Italian captain Monti with a tackle that he seemed to launch from some where just north of Leeds. Monti went up in the air like a rocket and down like a bag of hammers and had to leave the field with a splintered bone in his foot. Italy were starting to get the upper hand and laid siege to our goal. It was desperate stuff.

Our dressing room at half-time resembled a field hospital. We were 3-0 up but had paid a bruising price. No one had failed to pick up an injury of one sort of another. The language and comments coming from my England team-mates made my hair stand on end. I was still only 19 but came to the conclusion I'd been leading a sheltered life. I was relieved when our team trainer came into the dressing room, calmed everyone down and said that under no circumstances were we to copy the Italian tactics. We were to go out, he said, and play the way every English team had been taught to play. To do anything but, he said, would exacerbate the situation. Exacerbate the situation? It was already a bloodbath.

(6) Eddie Hapgood, Football Ambassador (1945)

Away we went, and, in fifteen minutes, had the match (apparently) well won. Inside thirty seconds we should have been one up, but Eric Brook's penalty effort was magnificently saved by Ceresoli, the Italian goalkeeper, and a very good one, too. But Eric made up for that. After nine minutes, he headed a cross from Matthews into the net, and, two minutes later, smashed in a second goal from a terrific free kick, taken just outside the penalty area.

Our lads were playing glorious football and the Italians, by this time, were beginning to lose their tempers. Barely had the cheers died down from the 50,000 crowd, than I ran into trouble. The ball went into touch on my side of the field, and, to save time, the Italian right-winger threw the ball in. It went high over me, and, as I doubled back to collar it, the right-half, without making any effort whatsoever to get the ball, jumped up in front of me and carefully smashed his elbow into my face.

I recovered in the dressing-room, with the faint roar from the crowd greeting our third goal (Drake), ringing in my ears, and old Tom working on my gory face. I asked him if my nose was broken, and he, busily putting felt supports on either side, and strapping plaster or, said it was. As soon as he had finished his ministrations, I jumped up and ran out on to the field again.

There was a regular battle going on, each side being a man short - Monti had also left the field after stubbing his toe and breaking a small bone in his foot. The Italians had gone beserk, and were kicking everybody and everything in sight. My injury had, apparently, started the fracas, and, although our lads were trying to keep their tempers, it's a bit hard to play like a gentleman when somebody' closely resembling an enthusiastic member of the Mafia is wiping his studs down your legs, or kicking you up in the air from behind.

Wilf Copping enjoyed himself that afternoon. For the first time in their lives the Italians were given a sample of real honest shoulder charging, and Wilf's famous double-footed tackle was causing them furiously to think.

The Italians had the better of the second half, and, but for herculean efforts by our defence, might have drawn, or even won, the match. Meazza scored two fine goals in two minutes midway through the half, and only Moss's catlike agility kept him from securing his hat-trick and the equaliser. And we held out, with the Italians getting wilder and dirtier every minute and the crowd getting more incensed. One of the newspaper men was so disgusted with the display that he signed his story "By Our War Correspondent."

The England dressing-room after the match looked like a casualty clearing station. Eric Brook (who had had his elbow strapped up on the field) and I were packed off to the Royal Northern Hospital for treatment, while Drake, who had been severely buffeted, and once struck in the face, Bastin and Bowden were patients in Tom Whittaker's surgery.