Tom Whittaker

Tom Whittaker was born in the East Cavalry Barracks at Aldershot on 21st July 1898. His father was a sergeant-major in the 12th Lancers. Three weeks after his birth the family moved back to the North-East.

As a boy Whittaker watched Newcastle United and was a great fan of Colin Veitch. After leaving school he became an apprentice at a large firm of marine engineers, Hawthorn, Leslie and Company in Newcastle.

In 1918 Whittaker was conscripted into the British Army. He was posted to Shoreham and played football for the Royal Garrison Artillery. This resulted in him having a trial with Woolwich Arsenal.

Whittaker was demobilised at the end of the First World War and began work as an engineer with Green, Silley & Wears, that was at the time working on the Blackwall Tunnel. In November 1919, Leslie Knighton, the manager of Arsenal, managed to persuade him to join the club. However, he did not resign his job as an engineer until he made his league debut against West Bromwich Albion on 6th April 1920.

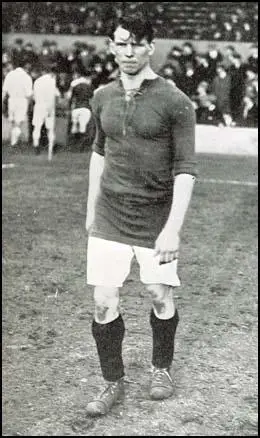

Whittaker was initially a centre-forward but in the 1920-21 season he was converted to left-half. Over the next three seasons he was a regular member of the Woolwich Arsenal side, playing in 64 league games. Whittaker was eventually replaced by Bob John as left-half and he went to left-back in the team.

In 1925 Whittaker took part in a Football Association tour of Australia. In a game against Wollongong he cracked a knee socket. He was told he would be off a long time and so he did a course in anatomy, massage and electrical treatment of injuries. When he returned to Highbury he was unable to train and therefore he helped in the treatment room.

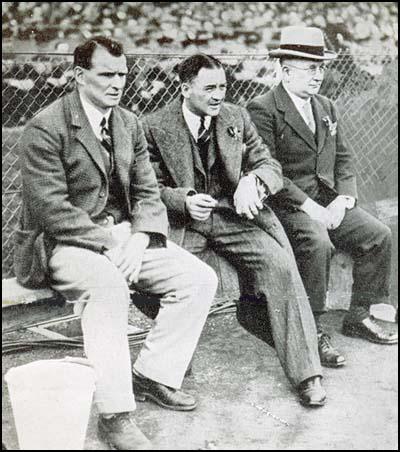

By 1926 it became clear that Whittaker's football career was over and Herbert Chapman appointed him as assistant trainer. On 2nd February, 1927, Arsenal played in a 4th round FA Cup tie against Port Vale. According to Whittaker: "Arsenal were pressing hard, but things were not going just right and old George Hardy's eyes spotted something he felt could be corrected to help the attack. During the next lull in the game he hopped to the touchline, and cupping his hands, yelled out that one of the forwards was to play a little farther upfield." Chapman was furious and sent Hardy to the dressing-room.

On the following Monday morning Herbert Chapman summoned Whittaker to his office and told him that he was now the first-team trainer. Chapman added: "I am going to make this the greatest club ground in the world, and I am going to make you the greatest trainer in the game."

When Herbert Chapman died on 6th January 1934, George Allison was appointed as the new manager. Allison was a radio journalist who was also the club's managing director. However, he had no experience of football management. At the time of Chapman's death Arsenal were top of the table and Tom Whittaker and Joe Shaw were allowed to run the team until the end of the season.

Sunderland was their main challengers to Arsenal in the 1933-34 season thanks to a forward line that included Raich Carter, Patsy Gallacher, Bob Gurney and Jimmy Connor. In March 1934 Sunderland went a point ahead. However, the Gunners had games in hand and they clinched the league title with a 2-0 victory over Everton.

The following season Whittaker returned to his job as first-team trainer. In this post he helped Arsenal win the league championship in the 1934-35 and 1937-38 seasons. He also worked as trainer for the England national team.

After the outbreak of the Second World War Whittaker became an Air Raid Warden while waiting to be accepted by the Royal Air Force. Most of the Arsenal's first-team, included Ted Drake, Jack Crayston, Eddie Hapgood, Leslie Jones, Bernard Joy, Alf Kirchen, Laurie Scott and George Swindon, became Physical Training instructors in the RAF. However, Whittaker refused this post and eventually became involved in the planning for D-Day operation. Promoted to the rank of Squadron Leader he won the MBE for his work during the war.

In 1945 Whittaker returned to his post as Arsenal's first-team trainer. George Allison resigned in 1947 and Whittaker agreed to become manager of the club. He lead the club to First Division championships in 1947-48 and 1952-53 and the FA Cup in 1950.

Tom Whittaker died of a heart-attack at the University College Hospital on 24th October 1956. His autobiography, The Arsenal Story, was published in 1957.

Primary Sources

(1) Tom Whitaker, The Arsenal Story (1957)

The youngsters of Newcastle and district, in fact the whole of the north-east, start their football lives early, and I was no exception.

Like many boys who were to become much more famous players than I, my early games consisted of hurriedly arranged scratch matches in the street, the ball made of rags wrapped round several sheets of paper and tied with string, or a "clouty baall," the Geordie's way of calling a cloth ball.

Alternative playing venue to the streets was to go "down the fields." The very small boys used to stand behind the goals when the older boys were playing and kick the ball back. Gradually, we used to edge our way into the game, usually to make up the number. If the little fellows were able to hold their own with the bigger boys, they became regular participants. Otherwise, back they went behind the goals made of coats!

Children were not catered for in the way they are today. Cinemas were more or less unheard of, books scarce. The only real outlet was the "patch," or as I have said, down the fields to play football so long as the season lasted. Then, with a crudely constructed bat, turn to cricket. But football was always the more popular.

Boys are great dreamers. When our rag ball went scuttering over the rough ground, I was Colin Veitch running in to shoot at the Aston Villa goal. we all make-believe, and there is no bigger day dreamer than the small, healthy boy.

(2) Tom Whitaker, The Arsenal Story (1957)

I was never a great player. I served the club as well as I knew how during the years following the Great War, held my place in the first team, lost it, and was still proud to play in the London (now "Football") Combination team, or the "stiffs," as it is known in the profession.

During that period, when destiny was shaping my future, I met and knew great players like Jackie Rutherford, whose superstition of entering the field of play last was upset in his final match for the club-v. Blackburn Rovers, Easter Monday, 1922 - before going to Stoke City as team manager. Rutherford was made captain for the day and came out first; Bert White, who was transferred to Blackpool the same week as he scored seven goals against the Athenian League; Billy Milne, the present Arsenal trainer, Fred Pagnam, Billy Blyth, dear old Joe Shaw, who left the club and then came back to take charge of the third team, and became the trusted chief scout at Highbury, Jack Butler, Scottish international Alex Graham, Bob John.

I played in front of Alf Kennedy, the young full-back, who, signed from Crystal Palace, was later to play in

our first Cup Final, against Cardiff in 1927. Other names come thick and fast, Alex Mackie, Joe Toner, Alf Baker, Dr. Paterson, Sid Hoar, A. V. Hutchins, Voysey, Williamson. There were others whose names, but not memories, have been erased by time.

I remember my first sight of the great Charlie Buchan when we went to Roker Park in 1922. I gave a penalty away in the first few minutes by handling the ball, and although I faithfully followed out the instructions to track Charlie all over the field, he had a great game. At the end we walked off together, and big Charlie said: "I am going home to tea when I've changed. Why don't you come? You might as well, you've followed me about all afternoon!"

The playing record of the club ran parallel with my own performances... "nothing to shout about." In season 1920-21 we finished ninth in the League, but for the most part we were struggling. Relegation was a constant danger, but somehow Arsenal managed to scramble clear at the last minute.

(3) Tom Whitaker, The Arsenal Story (1957)

Although Herbert Chapman did not start rebuilding the Arsenal team until 1927, he had, two seasons before, laid the foundations of the side which was to sweep all before them in the nineteen-thirties. At the beginning of the 1925-26 season, Arsenal struck a bad patch, playing so badly that in their ninth game they lost by 7-0 at Newcastle. Something had to be done, and, in effect, matters were precipitated after this match by big Charlie Buchan.

When the party was preparing for the night sleeper journey back to London, Charlie came up to Herbert Chapman and said: "Boss, I'm not coming back to London. I live here and I am staying up here." Startled, the Arsenal manager said, "What do you mean, you are staying here? We've got a match at West Ham on Monday, and you are playing." Says Charlie, doggedly, "There's no point in carrying on as we are. We've no plan, and the way the team is going, we will finish in the Second Division. I want to give up the game and stay up here in the North East."

Chapman persuaded Charlie to change his mind, promising him that something would be done. And so was born the "stopper" centre half plan, and the roving inside left. At the team conference on the morning of the game, Chapman asked for suggestions before proposing his own remedy. Whereupon the blunt Buchan upped and said, "Why not have a defensive centre half, or third full-back, to block the gap down the middle?"

Chapman agreed this was a possibility, but his quick-thinking brain saw that the scheme was lacking something, and that by turning an attacking centre half into a defender, some of the attacking power was lost. So Charlie suggested a roving inside forward. Again, the far-seeing Chapman saw the ramifications of this idea, and after a long discussion as to ways and means, it was decided to put the plan into operation that very afternoon.

Charlie Buchan has since confessed to me that he felt he, himself, should be the roving inside forward, but Chapman decided that the skipper would be of more help playing his normal game, and exclaimed, "I know the very man-Andy Neil. He's as slow as a funeral, but has ball control and can stand with his foot on the ball while making up his mind!" It mattered nothing that Andy Neil (who also played with Brighton and Kilmarnock) was at that time a third-team player. He was given the role.

And, contrary to popular belief, the first of the stopper centre halves was not Herbert Roberts, but Jack Butler. Later, of course, Herbie became the greatest of them all.

Arsenal won that first game, at West Ham, by 4-0, and went on winning. Jimmy Ramsey took over the inside left role and later gave way to Billy Blyth, when the great Blyth-Hoar wing was born. Arsenal finished second in the League that year, and might easily have won it but for that bad start. League champions that season were Huddersfield Town, finishing a hat-trick of championships, a feat which Arsenal were to repeat between 1932 and 1935. And the man who started Huddersfield on their run was Mr. Herbert Chapman, who was destined to revolutionise football at Highbury, but who did not live to see his beloved Arsenal become the champion of champions.