Bert Trautmann

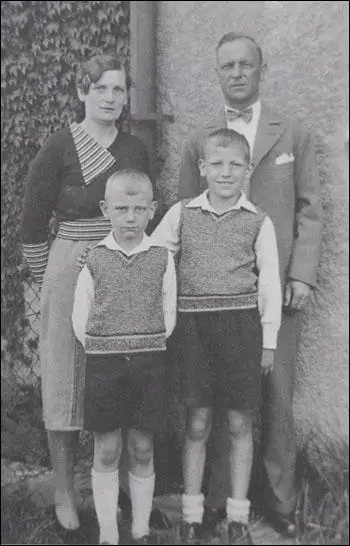

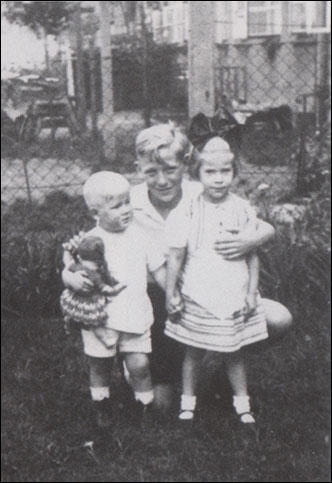

Bernhard (Bert) Trautmann, the eldest son of Carl Trautmann, a chemical loader at the docks, was born in Bremen, Germany, on 22nd October, 1923. (1)

In 1923 Germany was enduring an economic crisis. It was a time of rapid inflation and German currency was virtually worthless: "The purchasing power of wages had been reduced to nothingness and anyone with money in the bank had seen their savings wiped out." (2) In an attempt to defend living standards, the workers were involved in a series of strikes. (3)

In March 1926 Frieda Trautmann gave birth to another son, Karl-Heinz. Although Carl remained in work life was a constant struggle. He was a member of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) but most of his workmates were supporters of the growing Nazi Party. As a boy Bert observed fights between different political groups. During one demonstration in May 1931, three people were killed in Bremen and over a hundred seriously wounded. (4)

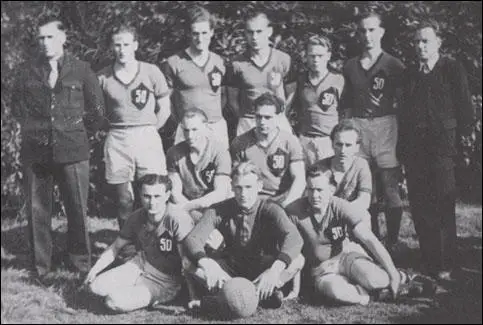

Bert Trautmann developed a reputation as an outstanding athlete. He was a talented footballer and was especially good at Völkerball. A game only played in Germany, it involved two teams of 10 on a small pitch divided into two halves. Each participant would throw the ball at the opposition; each player hit was removed from the game until one player was left. The game helped Trautmann's throwing ability and helped him when he played as a goalkeeper. (5)

Trautmann was an agressive young boy and was often involved in fights. In 1931 he so badly beat a boy that his head teacher considered the possibility of having him expelled and sent to a school of correction. Trautmann was encouraged to spend his energies on sport and he joined the Tura football team. (6)

Nazi Germany

Carl Trautmann was an active trade unionist and was concerned when the Nazi Party took power. Adolf Hitler proclaimed May Day, 1933, as a national holiday and arranged to celebrate it as it had never been celebrated before. Trade union leaders were flown to Berlin from all parts of Germany. Joseph Goebbels staged the greatest mass demonstration Germany had ever seen. Hitler told the workers' delegates: "You will see how untrue and unjust is the statement that the revolution is directed against the German workers." Later that day Hitler told a meeting of more than 100,000 workers that "reestablishing social peace in the world of labour" would soon begin. (7)

The next day, Hitler ordered the Sturm Abteilung (SA) to destroy the trade union movement. Their headquarters throughout the country were occupied, union funds confiscated, the unions dissolved and the leaders arrested. Large numbers were sent to concentration camps. Within a few days 169 different trade unions were under Nazi control. (8)

Carl Trautmann's fellow workers who were activists in the German Communist Party (KPD) and the Social Democratic Party (SDP) were soon arrested and sent to concentration camps. Bert remembers that it became common to call unpopular boys "commies" in school. (9) Strikes were now illegal and Carl was forced to make donations to the Nazi Party and the German Labour Front. In the Bremen docks, swastika flags were flown from every official building. Each time someone entered an office or a warehouse they had to give the Nazi salute. If it was not done with enough zeal you would be called into the local Gestapo headquarters. (10)

Bert Trautmann and the Hitler Youth

Before the Nazi government was formed the Hitler Youth only had 20,000 members. Non-Nazi youth organizations were far more popular. Hitler solved this problem by dissolving almost all the rival organizations (only Catholic youth organizations survived this measure). All boys and girls in Nazi Germany came under great pressure to join the Hitler Youth. By the end of 1933 there were 2.3 million boys and girls between the ages of ten and eighteen in the Hitler Youth organization. (11)

Bert Trautmann joined the junior branch of the organization on his tenth birthday. (12) "Bert Trautmann couldn't wait to join the Hitler Youth. His mother, better educated than his father, had her misgivings. Her bright boy, her special one, hardly bothered with school books these days. But begged by Bert and bombarded with Nazi propaganda, his parents scraped together the money it took to buy the uniform: short black trousers, khaki shirt, black necktie and leather toggle, plus a badge bearing the Hitler Youth insignia, a flash of lightning on a black background. Bert wore it with intense pride as he stood erect giving the Nazi salute before the swastika banner, hair shorn short back and sides." (13)

It was through the youth organisations that Hitler sought to build the new Germans for the future. "Look at these young men and boys! What material! With them I can make a new world.... My teaching is hard. Weakness has to be knocked out of them. In my Ordensburgen a youth will grow up before which the world will shrink back. A violently active dominating, intrepid, brutal youth - that is what I am after." (14)

In July 1936 the Hitler Youth had total control on the provision of sports facilities for all children below the age of fourteen. Soon afterwards, sports for 14-18 year-olds were subjected to the same monopoly. In effect, sports facilities were no longer available to non-members. On 1st December, 1936, the Hitler Youth was made a state agency. Now, every young person was expected to belong to the Hitler Youth. (15) The Hitler Youth now had 5 million members and was by 1937 the largest youth organisation in the world. (16)

Trautmann went to meetings twice a week in a wooden hut on a large allotment near his school. He was taught basic marching drills using broom handles as rifles. He remembers swearing an oath of allegiance to Adolf Hitler in front of a swastika flag: "In the presence of the blood banner, which represents our Führer, I swear to devote all my energies and my strength to the saviour of our country, Adolf Hitler. I am willing and ready to give up my life for him, so help me God." (17) Trautmann really believed what he was saying at the time. He later recalled that "growing up in Hitler's Germany, you had no mind of your own." (18)

Bert Trautmann was highly valued by the Hitler Youth as he combined great sporting talent and Aryan looks: "The newspapers and cinemas were soon full of it (the Hitler Youth)... idealised images of blond young athletes in white vests and flannels, shot-putting, hurdling, running, javelin throwing, swinging on the parallel bars; whole fields of them putting on a display of gymnastics at some Nazi rally, row upon row of perfect Aryan specimens, muscles taut, eyes blank, all facing the Führer standing on a distant podium festooned with laurel leaves and swastikas, flanked by Himmler, Göring, Goebbels and the rest." (19) In June 1934 Trautmann was only one of two boys in Bremen to be presented with a certificate of achievement, signed by President Paul von Hindenberg, for his "unsurpassed level of athletic ability." (20)

Education

Trautmann attended the local school in Bremen. His class teacher, Herr Koenig, wore knickerbockers and tweed jackets and embodied all the traditional values of Germanic education. Koenig did not approve of the Nazi Party and before 1933 he would often pass negative comments about Hitler. Three months after they came to power the Law for the Reconstruction of the Civil Service was introduced. All teachers now had to give their full support to Hitler or they could be brought in for questioning by the local Gestapo and face the possibility of losing your job. (21)

Adolf Hitler immediately made changes to the school curriculum. Education in "racial awareness" began at school and children were constantly reminded of their racial duties to the "national community". Biology, along with political education, became compulsory. Children learnt about "worthy" and "unworthy" races, about breeding and hereditary disease. "They measured their heads with tape measures, checked the colour of their eyes and texture of their hair against charts of Aryan or Nordic types, and constructed their own family trees to establish their biological, not historical, ancestry.... They also expanded on the racial inferiority of the Jews". (22)

As Louis L. Snyder has pointed out: "There were to be two basic educational ideas in his ideal state. First, there must be burnt into the heart and brains of youth the sense of race. Second, German youth must be made ready for war, educated for victory or death. The ultimate purpose of education was to fashion citizens conscious of the glory of country and filled with fanatical devotion to the national cause." (23)

Trautmann later admitted that he was completely taken in by this Nazi ideology and was a committed supporter of Adolf Hitler. As he explained to Catrine Clay, the author of Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010), that many times he came out of his flat to find the street covered in blood as a result of the beatings that socialists and trade unionists had received at the hands of the Sturmabteilung (SA): "What could he do? What, for that matter, could he do about the Jewish children, who disappeared from his school following the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, which barred all Jews from state schools... The answer in Bert's case, as with most other people in the Reich, was nothing; just get on with his life, which for Bert meant sport." (24)

Trautmann spent so much time with the Hitler Youth that his school work suffered and he failed to win a place at the Gymnasium. Instead he was sent away in 1938 to Görlitz to carry out Labour Service. "The regime the boys were now under became tightly organised and more militaristic. A reveille was held at 5.30 each morning and the khaki uniforms of the I litler Youth were replaced by harsh grey working uniforms with short trousers. After the flag had been raised they ate breakfast, usually sausage, cheese and bread, before being allocated duties for the day. Their names were chalked on a large blackboard, each under a specific heading. The majority were allocated to farm work with others given kitchen duty, cleaning chores or guard duty."

Trautmann found the work very hard: "It was a small farm, around 200 acres, and was surrounded by woods and streams. The farm was devoid of any mechanisation, Bernhard had to walk or travel by horse and cart to work. The main crops were potatoes, oats and wheat and the planting and reaping were done with horse-drawn wooden ploughs or hand ploughs. Bernhard thrived on the farms, his years of terrorizing the farmers in Bremen turned to a natural accord with the land. The Land Jahr boys were protected by regulations, however. They were not allowed to work over seven hours a day and were not to lift anything over 20 kilos. The work on the farm covered everything from painting and repairing the fences or poultry houses, to feeding the pigs and milking the cows." (25)

Kristallnacht

It was while he was in Görlitz that he heard about Kristallnacht (Crystal Night). On 11th November, 1938, Reinhard Heydrich reported to Hermann Göring, details of the night of terror: "74 Jews killed or seriously injured, 20,000 arrested, 815 shops and 171 homes destroyed, 191 synagogues set on fire; total damage costing 25 million marks, of which over 5 million was for broken glass." (26) It was decided that the "Jews would have to pay for the damage they had provoked. A fine of 1 billion marks was levied for the slaying of Vom Rath, and 6 million marks paid by insurance companies for broken windows was to be given to the state coffers." (27)

Trautmann and the other boys heard about Kristallnacht from the radio. They had been taught to hate the Jews and remembers them all shouting out "serve them right". (28) On his return to Bremen in December 1938 Trautmann was able to witness what had happened to the Jews in the city: "The Jewish community in Bremen were subjected to the appalling treatment as much as the rest of their race in the country... The Jews were the merchants and money lenders in the port and had a major influence in building up the prosperity, but their houses had been gutted by fire and their businesses vandalised and closed." (29)

Trautmann remembers watching The Eternal Jew in Bremen. "He thought it would be one of those short propaganda films you had to endure for a while before the main feature, but this one went on and on. Apparently the Jews had spread like rats through Europe, and then the entire world; now they were responsible for most of international crime and 98 per cent of prostitution. At the same time they bagged all the best jobs and earned all the money. Really, thought Bernhard, they deserved what was coming to them. He knew that one of his father's drinking companions had got into serious debt because of a Jew. The poor fellow had lost his job at the ammunitions factory for some reason, and he had four children to feed. Herr Trautmann was always buying him beers. On the other hand Bernhard had also seen a couple of incidents in shop queues, where Jews were dragged out and beaten up, which wasn't pleasant. But if you made a fat profit out of other people's bad luck, you were bound to be resented, weren't you?" (30)

Second World War

In January 1939, Trautmann began a four-year apprenticeship with Hanomag, a large diesel truck manufacturer, "an occupation for which he showed natural aptitude". (31) Now aged fifteen, he played for a local football team on Sunday mornings: "Bernhard played centre-forward, aggressively barging past anyone who got in his way - he hardly knew where he got it from, this will to win. The talent for the game came from his father, he knew, but the aggression, the attack, the temper when one of his team made a bad pass, this was all his own." (32)

Trautmann was very keen to join the armed forces so that he could take part in the Second World War. As soon as he reached the age of seventeen in October 1940, he volunteered for the armed forces: "I volunteered when I was 17. People say why?, but when you are a young boy war seems like an adventure." (33) He attempted to join the Luftwaffe as a communications specialist, but failed his code exams. (34) He was now assigned to become a paratrooper and he completed his training in May 1941. The following month he joined the soldiers about to take part in Operation Barbarossa. However, instead of being a front-line soldier, he was given the job of repairing military vehicles. (35)

Soon after arriving in the Soviet Union he got into some serious trouble. "He disabled a staff car as a prank so that he and some friends could go foraging once the officers had found another vehicle. When sand was found in the engine, Trautmann was convicted of sabotage and sentenced to nine months in a squalid former Soviet prison at Zhitomir." (36) While in prison he was diagnosed with appendicitis. Only an emergency operation saved his life. After he recovered he was sent back to the front line in time for his 18th birthday. (37)

Trautmann went into action against the Russian Fifth Army. According to Alan Rowlands, the author of Trautmann: The Biography (2011), Trautmann did not have too much problem killing Russians: "He returned fire against some anonymous grey figure who dropped like a stone. That was it - no feeling of revulsion or guilt, just nothing. The mixture of fear, self-preservation and fatigue whittled down normal sensibilities to a detached pragmatism." (38) While fighting in Ukraine, he and a friend inadvertently stumbled across a massacre of Jews by SS officers in a forest. "After being herded into trenches, they were systematically shot. Terrified, the pair escaped undetected and never spoke of the incident". (39)

In November 1941, Trautmann's regiment was sent to Smolensk. The weather and the actions of the partisans made progress difficult. That winter the German Army lost 100,000 soldiers through frostbite. "They did not necessarily die of it, but lost limbs or had their ears, toes and fingers turn black, ballooning like cauliflowers, and had to be hospitalised, and were out of the battle." (40)

General Heinz Guderian, commander of the 2nd Panzer Army, recorded a temperature of minus 36 degrees: "Our men just stand about miserably burning the precious petrol to keep warm... Several times we found sentries fallen asleep, literally frozen to death... Many men died while performing their natural functions, as a result of a congelation of the anus". (41)

Adolf Hitler suggested to his generals that the only was to defeat the Soviet Union was to terrorize the population of the occupied areas. "In view of the vast size of the occupied areas in the East, the forces available for establishing security will be sufficient only if all resistance is punished not only by legal prosecution of the guilty, but by the spreading of such terror by the occupying forces as is alone appropriate to eradicate every inclination to resist amongst the population." (42)

Bert Trautmann took part in these atrocities carried out against the Russians: "You didn't think of the enemy as people at first. Then, when you began taking prisoners, you heard them cry for their mother and father.... When you met the enemy, he became a real person. The longer the war went on, you started having doubts. But Hitler's was a dictatorial regime and you couldn't say what you wanted. In the German army, you got your orders and you followed them. If you didn't, you were shot." (43)

Stalingrad

In the summer of 1942 General Friedrich Paulus advanced toward Stalingrad with 250,000 men, 500 tanks, 7,000 guns and mortars, and 25,000 horses. At the end of July 1942, a lack of fuel brought Paulus to a halt at Kalach. It was not until 7th August that he had received the supplies needed to continue with his advance. Over the next few weeks his troops killed or captured 50,000 Soviet troops but on 18th August, Paulus, now only thirty-five miles from Stalingrad, ran out of fuel again. (44)

Joseph Stalin insisted that the city should be held at all costs. One historian has claimed that he saw Stalingrad "as the symbol of his own authority." Stalin also knew that if Stalingrad was taken, the way would be open for Moscow to be attacked from the east. If Moscow was cut off in this way, the defeat of the Soviet Union was virtually inevitable. A million Soviet soldiers were drafted into the Stalingrad area. They were supported from an increasing flow of tanks, aircraft and rocket batteries from the factories built east of the Urals, during the Five Year Plans. Stalin's claim that rapid industrialization would save the Soviet Union from defeat by western invaders was beginning to come true.

The heavy rains of October turned the roads into seas of mud and the 6th Army's supply conveys began to get bogged down. On 19th October the rain turned to snow. Paulus continued to make progress and by the beginning of November he controlled 90 per cent of the city. However, his men were now running short of ammunition and food. Despite these problems Paulus decided to order another major offensive on 10th November. The German Army took heavy casualties for the next two days and then the Red Army launched a counterattack. Paulus was forced to retreat southward but when he reached Gumrak Airfield, Adolf Hitler ordered him to stop and stand fast despite the danger of encirclement. Hitler told him that Hermann Goering had promised that the Luftwaffe would provide the necessary supplies by air.

Now aware that the 6th Army was in danger of being starved into surrender, Adolf Hitler ordered Field Marshal Erich von Manstein and the 4th Panzer Army to launch a rescue attempt. Manstein managed to get within thirty miles of Stalingrad but was then brought to a halt by the Red Army. On 27th December, 1942, Manstein decided to withdraw as he was also in danger of being encircled by Soviet troops. (45)

In Stalingrad over 28,000 German soldiers had died in just over a month. With little food left General Friedrich Paulus gave the order that the 12,000 wounded men could no longer be fed. Only those who could fight would be given their rations. Erich von Manstein now gave the order for Paulus to make a mass breakout. Paulus rejected the order arguing that his men were too weak to make such a move. On 30th January, 1943, Hitler promoted to Paulus to field marshal and sent him a message reminding him that no German field marshal had ever been captured. Hitler was clearly suggesting to Paulus to commit suicide but he declined and the following day surrendered to the Red Army. (46)

Prisoner of War

In May 1944 Trautmann was sent to France to join the forces involved the formation of the Atlantic Wall, an extensive system of coastal defence and fortifications built along the coast of continental Europe and Scandinavia as a defense against an anticipated Allied invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe. The following month his unit captured a number of paratroopers who had landed behind German lines during the D-Day invasion.

It now became clear to Trautmann and his fellow German soldiers that defeat was inevitable. The soldiers were given leaflets that said: "Certain unreliable elements seem to believe that the war will be over for them as soon as they surrender to the enemy. Every deserter will find his just punishment. Furthermore, his ignominious behaviour will entail the most severe consequences for his family - they will be summarily shot." (47)

Trautmann, promoted to the rank of corporal, and the rest of his regiment retreated. While regrouping in the German town of Kleve, he was buried alive for three days when the Allies bombed a school where his unit was billeted; most of his comrades were killed. Soon afterwards he was captured by Allied troops. (48) Trautmann was one of only 90 members of his original 1,000-strong regiment still alive by the end of the war. (49)

Trautmann, the 22-year-old "veteran" was sent to England as a prisoner of war. Members of the German armed forces were interrogated before being classified into three categories: White for anti-Nazis, Grey for unsure and Black for convinced Nazis. Around 10 per cent, including Trautmann, were judged to be a convinced Nazi.

Trautmann and his fellow prisoners were shown a film of the Belsen concentration camp: "There were great piles of naked corpses, no more than skeletons but with hair, their legs and arms indecently splayed as bulldozers driven by British soldiers dumped them into massive pits.... It was easy enough to pick out the ardent Nazis, protesting their outrage and objecting that the film was a fake, but perhaps they also noticed the ones who filed past in silence, eyes to the ground, like Trautmann." (50)

Bert Trautmann was later sent to a camp in Ashton-in-Makerfield "revelling in the camaraderie and relishing conditions which amounted to luxury compared to his recent privations". (51) The Geneva Convention stated that prisoners of war should be repatriated once hostilities ceased. Clement Attlee, prime minister of the post-war Labour Party government rejected this idea. He insisted that German POWs should stay and repair the damage that the Luftwaffe had caused. Attlee also thought that as these soldiers had been brainwashed in Nazi Germany they would need a period of re-education. Trautmann complained that these were often long and boring subjects such as the "Constitution of the British Empire". (52)

By early 1946 there were over 400,000 German POWs in Britain. "There was hardly a town or village which didn't have a POW camp nearby, and the British civilians got used to seeing them marching out of the camp, two by two, in their brown uniforms with the yellow diamond patches, to work on building sites, clearing bomb damage or mending roads and railway tracks, or, more often, sitting in the back of a lorry, off to one of the local farms." (53)

Trautmann worked as a driver for Jewish officers on the camp. "They wanted to know what you thought about Nazis and the Jewish community," says Trautmann, who admits that "deep down" he then still viewed "Jews as moneylenders and profiteers". (54) In March 1946, Trautmann had to drive one of these Jewish officers to a POW camp. The man had been a university professor and according to Trautmann it was his superior manner that triggered feelings of inferiority about his own inadequate schooling. They had an argument and the officer called him a "German pig". Trautmann hit the officer and drove off leaving him lying by the side of the road. He was found guilty of assault and sentenced to fourteen days detention. (55)

Manchester City

In 1946 Trautmann met Marion Greenall a woman who lived in Ashton-in-Makerfield. Shortly afterwards, the nineteen year old Marion became pregnant. Her parents complained to the commander of the camp but despite considerable pressure from all concerned, Trautmann refused to marry Marion. (56)

Trautmann, like all German POWs, was released in 1948. However, Trautmann wanted to remain in England and had enjoyed playing football for local teams. He found work on a farm in Milnthorpe. After the birth of his daughter, Freda, he had to pay Marion Greenall 10 shillings a week. He also played for St Helens Town where he soon gained a reputation as an outstanding goalkeeper. To reduce travelling time he found work with a bomb disposal unit in Huyton. (57)

Frank Swift, who played in goal for England and Manchester City, retired from the game at the end of the 1948-49 season. The manager of the club, Jock Thomson, decided to sign Trautmann to replace Swift. (58) Manchester had a large Jewish community and they began a campaign to stop him playing for the club. In October 1949, 25,000 fans demonstrated outside the Maine Road Stadium, shouting and waving placards emblazoned with swastikas, "Nazi" and "War Criminal" threatening to boycott the club unless they got rid of the German.

Ivan Ponting has pointed out: "The big, muscular German was embroiled in harrowing controversy. A large and vociferous faction of Manchester’s extensive Jewish community objected vigorously to the employment of a former paratrooper so soon after the war. Others joined what became an hysterical campaign, with Trautmann subjected to a flood of hate mail and more reasoned, if equally heated, letters appearing in the press. Some ex-servicemen threatened to boycott City if the new goalkeeper remained." (59)

One fan wrote to the local newspaper: "When I think of all those millions of Jews who were tortured and murdered, I can only marvel at Manchester City's crass stupidity". Another wrote, "I have been a City supporter for forty-five years but if this German plays, I will ask members of the British Legion and the Jewish ex-Servicemen's Club to boycott the City Club." The newspapers also published several letters from supporters who had fought against Nazi Germany in the Second World War and complained that the signing was an insult to their comrades who had been killed in the conflict.

The Manchester Evening News published a series of letters on the signing of Trautmann. One wrote: As a disabled serviceman from the last war I am writing with bitterness in my heart. To think that after all we in this country went through and still are going through due to the war, Manchester City sign a German. I have followed City up and down the country and will cease to follow my club if they sign this man."

However, others supported the decision: "Racial antagonism ought not to be perpetuated like this. Sport should be one of the means of reconciliation not of wider division - the protests of some ignore the reality of what active service experience the two world wars proclaimed - that between front-line soldiers there is no real personal hatred. The German soldier and the British tommy were only obeying orders. Moreover what have racialism and past national antagonisms to do with this game of football - one would think that the player was the Belsen Camp commandant - when born a German he had to do his duty as a German." (60)

Trautmann was also helped by the fact that Manchester City's captain, Eric Westwood, had taken part in the D-Day landings and had been mentioned in dispatches. He was considered to be a war hero and it was claimed that when he was introduced to Trautmann he had said: "There's no war in this dressing-room, we welcome you as any other member of the staff. Just make yourself at home, and good luck." (61)

Bert Trautmann made his debut in the First Division against Bolton Wanderers on 19th November, 1949. The catcalls started as soon as Bert Trautmann emerged from the tunnel. Chants by the Bolton supporters such as "Nazi" and "Heil Hitler" continued right through the game. Bolton won the game 3-0 and Trautmann was considered to be at fault for the first goal.

Before his first home game, Alexander Altmann, the communal rabbi of Manchester, urged the fans to treat Trautmann with respect: "Each member of the Jewish Community is entitled to his own opinion, but there is no concerted action inside the community in favour of this proposal (to force him out of the club). Despite the terrible cruelties we suffered at the hands of the Germans, we would not try to punish an individual German, who is unconnected with these crimes, out of hatred. If this footballer is a decent fellow, I would say there is no harm in it. Each case must be judged on its own merits." (62)

According to Bert Trautmann this was an important intervention: "Thanks to Altmann, after a month it was all forgotten... Later, I went into the Jewish community and tried to explain things. I tried to give them an understanding of the situation for people in Germany in the 1930s and their bad circumstances. I asked if they had been in the same position, under a dictatorship, how they would have reacted? By talking like that, people began to understand." (63)

The expected large-scale boycott of his first home game against Birmingham City did not take place. "In the event, the threatened action by the supporters was limited, but a few supporters did stay away, a small group made a protest outside the stadium, while some season tickets were returned. The City supporters in general were concerned for their team and now this new player was a crucial element of that team, their fanatical allegiance and loyalty transcended any prejudice."Trautmann was also helped by the 4-0 victory. (64)

Trautmann was his first visit to bomb-ravaged London. For most of the first half against Fulham he had to endure the most malicious chants he had ever received. However, he played so well that as Trautmann "walked off the field at the end of the game the whole stadium stood up, cheering him, and the two teams lined up on either side of the players' entrance, clapping him off." (65)

Over the next few years Bert Trautmann became one of the stars of British football: "A huge and commanding figure radiating authority between the posts, he combined agility and sharp reflexes with boundless courage and a highly developed positional sense. At times he was a showman, playing shamelessly to the gallery; at others he frustrated opponents with the apparent ease of his saves, gathering powerful shots calmly in his bucket-like, seemingly prehensile hands." (66)

Trautmann married his girlfriend, Margaret Friar, on 30th March 1950. His parents were unable to attend due to ill health and lack of money. His son, John, was born seven months later. The marriage was unsuccessful: "Margaret loved the glamour of football and the local fame, but she wasn't happy with how much of Bert's time and energy the game consumed, and the way the women still threw themselves at him." (67)

Footballer of the Year

In 1955 Manchester City reached the FA Cup Final and played Newcastle United who were attempting to win it for the third time in five years. Jackie Milburn scored after sixty seconds but it was the 18th minute injury to Jimmy Meadows. City did manage an equaliser when Bobby Johnstone headed in a cross from Joe Hayes. Newcastle made their numerical advantage, tell in the second-half, and scored via Bobby Mitchell and George Hannah. (68)

Trautmann later admitted that he had been terribly nervous before the game. "We didn't see a great deal of each other during those last few minutes before we left the dressing room. We were too busy dashing to and from the toilets." Trautmann blamed himself for two of the goals. Don Revie later commented that they did not lose the game because of the goalkeeper. "The plain truth is that I believe it is impossible to win a Cup Final at Wembley with ten men... Wembley has lovely turf but it takes a lot out of the leg muscles, extremely tiring when you have to do all the chasing." (69)

The following year Manchester City reached the semi-final of the FA Cup. The match was against Tottenham Hotspur, a team that had a large Jewish following and the week before the game he received a lot of hate mail. City won the match 3-1 but Trautmann received a lot of criticism when he fouled George Robb by holding his leg, stopping a certain Tottenham goal. "The newspapers were full of it that weekend. The photos were damning, and Bert felt he'd let himself down." (70)

Football Writers' Association voted Bert Trautmann the Footballer of the Year. He was the first goalkeeper and the first foreigner to be given this award. However, several writers disagreed with this decision, mainly because of the George Robb incident. "Despite a fairly heated debate, Trautmann's detractors lost the argument, and he finally received three times the number of votes of any other nominee. At the age of 32 he had received England's greatest accolade." On 3rd May 1956, Bert Trautmann collected the award at the Criterion Restaurant. (71)

The 1956 Cup Final took place two days later. Manchester City took an early lead. As Frank Swift reported in the News of the World. "Only three minutes had ticked by when Revie, in his old deep centre forward role... He laid the foundations... when he swept out a lovely pass to left winger Roy Clarke, raced in to collect the return and cutely backheeled a gilt edged chance for Joe Hayes. And Joey put the ball in the proper place - Birmingham's net!" (72)

Noel Kinsey scored for Birmingham City but in the second-half Jack Dyson and Bobby Johnstone put Manchester City 3-1 in front. As Brian Glanville pointed out: "City were comfortably in command when, with around a quarter of an hour left, Peter Murphy chased a Birmingham pass into the penalty box. Trautmann rushed out, recklessly brave as ever, and dived head first for the ball. Murphy found his knee connecting with Trautmann's neck. After treatment on the field, Trautmann was not accompanied off it: substitutes were not allowed, so City would have had to continue with 10 men. Astoundingly, Trautmann somehow managed to play on in great pain; only afterwards, when he was X-rayed, was it discovered that his neck had been broken." (73)

The trainer, Laurie Barnett, rushed onto the pitch, and asked Trautmann if he could carry on. He added that there was "only fourteen minutes left". Trautmann said later: "That was the last thing I remember." (74) Journalist Eric Thornton, wrote in the Manchester Evening News: "I will never forget helping trainer Barnett with a dressing room massage to ease the pain in Trautmann's neck at the end of the Wembley triumph. He put both his great hands on my shoulders, and said, The pain stabs right through me. Came a second's pause. Then he added, But it's worth it. I don't care if the pain's like a red-hot poker. I know I got the Cup medal in my wallet." (75)

Trautmann was taken to hospital and it was discovered that he had a broken neck. His second vertebra was broken in two and lodged against a third, which held the fragments in place and so saved his life. (76) The examining doctor told Trautmann that just one jolt of the bus back from Wembley could have killed him. (77) "They drilled holes in my head and put calipers in, like U-shaped hooks. I had to lie on a bed of boards, no mattress, no nothing, just a sheet and a blanket... They put me in plaster from my head to my waist, only keeping my arms free, and the calipers were still in, so I looked like something from outer space... I was completely immobilised... The doctors warned me I'd never play top football again." (78)

On 25th May, 1956, Margaret Trautmann became involved in a discussion with a friend, Stan Wilson. John, her five year old son, asked for money to purchase some sweets from a mobile confectionary shop on the other side of the road. (79) Bert Trautmann later recalled details of what happened: "There was a Tip Top bread and sweets van on the other side of the road, and John asked for some money to buy some sweets. He crossed the road to get them, but didn't have the extra penny for the sweets he wanted, so he ran back across the road, without looking, to ask for some more. He didn't see the car coming... The driver of the car was a boy of seventeen. He'd only just passed his test, and he was half German actually, just like John. The wife saw it all. She was on the pavement, and as he came running back over, the car hit him, and he was flung in the air just three yards away from her." (80) Although his wife bore him two more boys, Mark and Stephen, she never recovered from the death of his first son. "Margaret didn't get over John, she had no interest in life any more." (81)

Trautmann was told he would never play football again but he regained his place the following season and according to Ivan Ponting "Though never quite as acrobatic as before, Trautmann regained his position as one of the world’s leading goalkeepers." (82)

Bert Trautmann 1964-2013

When he retired in 1964 Trautmann had played 508 games for Manchester City. In 1966 he became manager of Stockport County. "The team won promotion to the Third Division and the gates rose, but then he had a row with the chairman and walked out." (83) He also managed Preußen Münster (1967-68) and Opel Rüsselsheim (1968-69). He was also employed by the German government to coach in Burma, Tanzania, Liberia and Pakistan. "Excellent times. I was teaching people how to be football coaches, but they all taught me a hell of a lot about life, about tolerance and thinking differently." (84)

Trautmann's marriage to Margaret ended in divorce in 1971. His second marriage, to Ursula von der Heyde, lasted eight years. He married his third wife, Marlis in 1986 and he owned a vineyard near Valencia. He followed the Premiership on satellite television and was a regular visitor to Britain: "My education only began the day I arrived in England... The British made me what I am... When I visit Germany, they say to me: Be honest, you’re English through and through. And I’m mighty proud so to consider myself. I come back four or five times a year and always think Great, I’m home." (85)

Bert Trautmann died following a heart-attack in La Llosa on 19th July 2013.

Primary Sources

(1) Catrine Clay, Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010)

Bert Trautmann couldn't wait to join the Hitler Youth. His mother, better educated than his father, had her misgivings. Her bright boy, her special one, hardly bothered with school books these days. But begged by Bert and bombarded with Nazi propaganda, his parents scraped together the money it took to buy the uniform: short black trousers, khaki shirt, black necktie and leather toggle, plus a badge bearing the Hitler Youth insignia, a flash of lightning on a black background. Bert wore it with intense pride as he stood erect giving the Nazi salute before the swastika banner, hair shorn short back and sides, and spoke the oath: "In the presence of the blood banner, I swear to devote all my powers and my strength to the saviour of our Reich, Adolf Hitler. I am willing and ready to give up my life for him, so help me God." No one in the Hitler Youth movement seemed to think it strange for a young boy, keen on sport and other outdoor pursuits, to swear an oath to give up his life for the Führer, should the moment arrive.In 1932 membership of the Hitler Youth had been 107,950. In 1933, after the Nazis came to power, it rose swiftly to 2,300,000 out of a total of 7,529,000 German youth. By 1936 it had risen to 5,400,000 out of a total of 8,656,000. By 1939, at the outbreak of the Second World War, it had reached 8,700,000 out of a total of 8,870,000. Those young boys you see in newsreels with a trembling Hitler in the spring of 1945, just weeks before the end of the war, boys no more than fourteen years of age saluting their Führer with pride in the face of certain defeat, those are the final intake of the Hitler Youth, the last gasp of the dream of a Thousand Year German Reich.

The great leap in membership in 1936 did not happen by accident. In 1934 the party had already issued a proclamation, posted at every street corner... Hitler Youths stood by the posters handing out the forms. Schools were ordered to put up lists in every classroom noting which boys were members, and which weren't. Those who weren't on a list soon received a letter, enclosing the form. Both the father and the son had to sign.

In 1936 came the first Hitler Youth Order, marking the moment when the Nazi Party decided that enough was enough. From now on measures would be taken to force all German youths between the ages of ten to eighteen to join, because time was running out: war was imminent. If a youth or a parent resisted, they would be fined and given a warning, if they continued to resist, the father might find himself out of a job. After that it was to one of the concentration camps, which were springing up all over Germany, designed to contain anyone who opposed the party: communists, socialists, Jews or fathers who didn't want their sons joining the Hitler Youth.

(2) Alan Rowlands, Trautmann: The Biography (2011)

On his 14th birthday (22nd October, 1937)... he had become a member of the Hitler Youth movement proper. Together with half a dozen others, another histrionic ceremony had been staged before the unfurled Nazi banners, and each boy repeated his allegiance to the Fiihrer, receiving the organisation's dagger engraved with the words "Blood and Honour". The Jugend group met at his school, and the classrooms were used to teach boys of their role in the new German society. The lectures did not contain anti-Semitic ravings or any hostile references to other countries or cultures. They still concentrated on the Aryan characteristics of strength and invincibility and how these qualities were to be used for the good of Germany. Similarly, the camping and hiking trips continued to concentrate on survival techniques and an appreciation of self-discipline. The summer of 1937 proved to be the last one together for the Trautmann gang; their fates were now being controlled by the puissant minds of the men controlling a re-emerging German nation.

In early 1938 Bernhard travelled in a group of 50 boys from Bremen and Lower Saxony on the long train journey to Görlitz in Eastern Germany. From there they were taken to a schloss - a small castle - at Schoebersdorf, next to the farm on which they would be working. After a speech of welcome from the Land Jahr leaders, they were shown to the dormitories, given a tour of the schloss and then taken to meet the large, ruddy-faced man for whom they would be working, farmer Flenning.

The regime the boys were now under became tightly organised and more militaristic. A reveille was held at 5.30 each morning and the khaki uniforms of the I litler Youth were replaced by harsh grey working uniforms with short trousers. After the flag had been raised they ate breakfast, usually sausage, cheese and bread, before being allocated duties for the day. Their names were chalked on a large blackboard, each under a specific heading. The majority were allocated to farm work with others given kitchen duty, cleaning chores or guard duty.

It was a small farm, around 200 acres, and was surrounded by woods and streams. Around the perimeter fencing, sentry boxes had been erected and each boy had to do a stint of guard duty split into two shifts, from six in the morning until two in the afternoon and from two until ten o'clock at night. They were marched in single file, with spades on their shoulders substituting for rifles, to take up their guard positions. They were subject to inspections at any time.

The farm was devoid of any mechanisation, Bernhard had to walk or travel by horse and cart to work. The main crops were potatoes, oats and wheat and the planting and reaping were done with horse-drawn wooden ploughs or hand ploughs. Bernhard thrived on the farms, his years of terrorizing the farmers in Bremen turned to a natural accord with the land. The Land Jahr boys were protected by regulations, however. They were not allowed to work over seven hours a day and were not to lift anything over 20 kilos. The work on the farm covered everything from painting and repairing the fences or poultry houses, to feeding the pigs and milking the cows.

(3) Catrine Clay, Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010)

Bernhard was sitting in the cinema a couple of weeks later, watching Der Ewige Jude (The Eternal Jew). He thought it would be one of those short propaganda films you had to endure for a while before the main feature, but this one went on and on. Apparently the Jews had spread like rats through Europe, and then the entire world; now they were responsible for most of international crime and 98 per cent of prostitution. At the same time they bagged all the best jobs and earned all the money. Really, thought Bernhard, they deserved what was coming to them. He knew that one of his father's drinking companions had got into serious debt because of a Jew. The poor fellow had lost his job at the ammunitions factory for some reason, and he had four children to feed. Herr Trautmann was always buying him beers.

On the other hand Bernhard had also seen a couple of incidents in shop queues, where Jews were dragged out and beaten up, which wasn't pleasant. But if you made a fat profit out of other people's bad luck, you were bound to be resented, weren't you? Still, he was pleased when the tone of the film started to lift, in expectation of the usual rousing ending. "Under the leadership of Adolf Hitler, Germany has raised the battle flag against the eternal Jew," it proclaimed. "The eternal law of nature, to keep one's race pure, is the legacy which the National Socialist Movement bequeaths to the German people for all time."

(4) Louise Taylor, The Guardian (11th April 2010)

Bert Trautmann begins looking a little bored when the broken neck is mentioned. After spending almost an hour discussing Nazism, the horror of war, antisemitism and failed relationships with impressive and sometimes chilling candour, the former Manchester City goalkeeper's still bright-blue eyes finally start glazing over."I've explained it 1,636 times on this trip already," he says, smiling thinly, as the conversation shifts to the 1956 FA Cup final and the day he played the last 16 minutes of City's triumph over Birmingham with a fractured neck. "Wherever I go, people always ask about my neck."

It had been no surprise when the 86-year-old German's visit to Eastlands last week, to promote Catrine Clay's brilliant new biography Trautmann's Journey, began with City's club doctor bounding towards him clutching an anatomical model of a human's upper body.

"I still have pain if I make unexpected movements of my head," says the one-time Luftwaffe paratrooper and holder of the Iron Cross, who will be rooting for City from the Eastlands directors' box during this afternoon's latest rematch with Birmingham. "But I was very lucky: surgeons told me I could have died or been paralysed."

Instead, Trautmann, in infinitely better shape than most men a decade younger, was able to continue living what he acknowledges is an "extraordinary, sometimes mad" life to the full.

Many of its happiest moments arrived in later years when, employed by the German government on a third-world initiative, he lived in Burma, Tanzania, Liberia, Pakistan and Yemen. "Excellent times," he says. "I was teaching people how to be football coaches, but they all taught me a hell of a lot about life, about tolerance and thinking differently."

By then Trautmann had already completed an incredible odyssey that swept this one-time Hitler Youth prodigy into active wartime service in Russia and later France. "I volunteered when I was 17," he says. "People say 'why?', but when you are a young boy war seems like an adventure. Then, when you're involved in fighting it's very different, you see all the horrible things that happen, the death, the bodies, the scariness. You can't control yourself. Your whole body is shaking and you're making a mess in your pants."

Trautmann was one of only 90 members of his original 1,000-strong regiment still alive in 1945. Several fellow survivors were left badly maimed. "I kept nothing from the war," he says. "I don't have my Iron Cross any more."

Earlier, he had endured a childhood of brainwashing, experiencing years of indoctrination during racial biology and ideology lessons in which messages that Jews were responsible for wrecking Germany's economy, that Poles were an inferior people and Aryans the master race had been repeatedly rammed home.

"Growing up in Hitler's Germany, you had no mind of your own," he says. "You didn't think of the enemy as people at first. Then, when you began taking prisoners, you heard them cry for their mother and father. You said 'Oh'. When you met the enemy, he became a real person. The longer the war went on, you started having doubts. But Hitler's was a dictatorial regime and you couldn't say what you wanted. In the German army, you got your orders and you followed them. If you didn't, you were shot."

After he escaped from the Russians and then the French resistance, the British finally captured him properly. "When they got me (after he had hurdled a fence leaping straight into an ambush) the first thing they said was: 'Hello Fritz, fancy a cup of tea,'" recalls Trautmann.

It was the start of an unlikely love affair. "I feel British in my heart now," he says. "When people ask me about life, I say my education began when I got to England. I learnt about humanity, tolerance and forgiveness." Not to mention that Jews were human, too.

Trautmann was told of concentration camps and the Holocaust in an English PoW camp, but his first intimation that something had gone very wrong came when, fighting in Ukraine, he and a friend inadvertently stumbled across a massacre of Jews by SS officers in a forest. After being herded into trenches, they were systematically shot. Terrified, the pair escaped undetected and never spoke of the incident. Trautmann bows his head at the memory: "I was 18."

German PoWs were routinely shown a film about Belsen. "My first thought was: How can my countrymen do things like that? he says. "But Hitler's was an utter totalitarian regime."

Later, the then 22-year-old worked as a driver for Jewish officers on the camp. "They wanted to know what you thought about Nazis and the Jewish community," says Trautmann, who admits that "deep down" he then still viewed Jews as moneylenders and profiteers.

"Sometimes their questioning was quite nasty, your pride was hurt and I lost my temper." So much so that after one called him a "German pig" Trautmann punched him.

Subsequent driving service for another Jew, Sergeant Hermann Bloch, proved much happier. "I quickly came to see Bloch, and every other Jew, as human beings. At first I sometimes lost my temper with him, but, in time, I talked to him as if he was just another English soldier. I liked him."

He also enjoyed playing centre-half for PoW teams across north-west England, only being persuaded to move into goal after one day becoming embroiled in an outfield fight. A star was born and, with Trautmann declining repatriation to Germany, a stint at non-League St Helens prefaced a high-profile move to Manchester City.

Manchester boasted a sizeable Jewish community and 20,000 demonstrated against City's new signing before Dr Altmann, the communal Rabbi, appealed for the German player to be offered a chance, reminding everyone that an individual should not be punished for his country's sins.

"Thanks to Altmann, after a month it was all forgotten," says Trautmann. "Later, I went into the Jewish community and tried to explain things. I tried to give them an understanding of the situation for people in Germany in the 1930s and their bad circumstances. I asked if they had been in the same position, under a dictatorship, how they would have reacted? By talking like that, people began to understand."

(5) Ivan Ponting, The Independent (19th July, 2013)

For most footballers, keeping goal in an FA Cup final while suffering from a broken neck would be the most dramatic, and traumatic, event of their lives. But for Bert Trautmann, by common consent among the finest goalkeepers in football history despite never playing for his country, an excruciating, life-threatening interlude at Wembley in 1956 was a mere trifle compared to what he had lived through already.Indeed, Trautmann counted himself fortunate to be still breathing, let alone playing for Manchester City in the English game’s annual showpiece. As a German paratrooper in the Second World War he had survived bloody battles and debilitating deprivations, first during his country’s abortive invasion of Russia and later while fighting to repel the Allies on the Western Front.

Then, after settling in England and choosing to make his living in the public eye, he faced a cruel barrage of racist vitriol from those who could not put aside the bitterness of the recent conflict. That he emerged from the ordeal as one of the best-loved and most highly respected players of his generation speaks volumes for the blond giant’s immense talent, his bullish strength of will and, not least, his sheer charisma.

A self-confident, gregarious, though rather quick-tempered boy, Trautmann grew up in a Germany in which the Hitler youth movement was gaining rampant momentum and, caught inexorably by the spirit of the times, he became a member. However, the ceaseless propaganda and indoctrination never turned him into a political zealot, most of his energy being concentrated on a wide range of sports. He was a natural athlete, representing the Silesia region in national championships at Berlin’s Olympic stadium in 1938, displaying the physical strength and dexterity that was to stand him in good stead in later life.

However, professional football was not on the horizon when Trautmann took his first job, as an apprentice car mechanic in Bremen, an occupation for which he showed natural aptitude. Soon after the war began he joined the Luftwaffe, yearning to be a pilot but serving as a wireless operator before transferring to the paratroop regiment. He was sent to Poland and thence to Russia, enduring the horrors and hardship of a long and fruitless campaign. Trautmann fought and killed in nightmarish conditions – the ground was frozen so hard that the dead could not be buried – before falling back to help combat the Allies’ advance into France. During this operation he emerged unscathed from a succession of scrapes, including capture by and escape from the Resistance when serving as a dispatch rider, before being taken for the final time as the Allies were mopping up after D-Day.

In 1945, having won five medals for bravery, the 22-year-old “veteran” was shipped, bewildered and fatigued, to England as a prisoner of war. He was placed in a camp at Ashton-in-Makerfield in Lancashire, where he was quick to recover his characteristic joie de vivre, revelling in the camaraderie and relishing conditions which amounted to luxury compared to his recent privations. He spurned the chance of repatriation, making a new start in a new land with jobs on a local farm and with a bomb-disposal unit.

Meanwhile, the seeds of future fame and fortune had been sown. At the camp Trautmann had played plenty of football, switching from his former position of rumbustious centre-forward to goalkeeper and discovering that he was enormously good at it. In 1948 he signed for St Helens Town, an enterprising non-League team with whom he made such rapid and gigantic strides that he was trailed by a small posse of leading clubs. Burnley appeared favourites to acquire his signature, but in November 1949 they were pipped by Manchester City, and a few weeks later Trautmann found himself pitched into First Division action.

Instantly, and inevitably, the big, muscular German was embroiled in harrowing controversy. A large and vociferous faction of Manchester’s extensive Jewish community objected vigorously to the employment of a former paratrooper so soon after the war. Others joined what became an hysterical campaign, with Trautmann subjected to a flood of hate mail and more reasoned, if equally heated, letters appearing in the press. Some ex-servicemen threatened to boycott City if the new ’keeper remained, season tickets were returned and there was predictable abuse at away grounds.

Trautmann’s dignified reaction spoke volumes for his strength of character, never more so than on his first visit to bomb-ravaged London. That day at Fulham he was confronted by the most malicious jibes to date, but he refused to be intimidated. As “Heil Hitler” chants resounded around a seething Craven Cottage he performed so magnificently that at the final whistle he was given a standing ovation by the majority of the crowd and the Fulham players formed a spontaneous guard of honour as he left the pitch.

Trautmann’s cause was furthered immeasurably by his ever-more outstanding prowess. A huge and commanding figure radiating authority between the posts, he combined agility and sharp reflexes with boundless courage and a highly developed positional sense. At times he was a showman, playing shamelessly to the gallery; at others he frustrated opponents with the apparent ease of his saves, gathering powerful shots calmly in his bucket-like, seemingly prehensile hands. It became apparent that here was a worthy successor to Frank Swift, City’s previous brilliant and much-loved goalkeeper, but the team was woefully poor, being relegated at the end of his first season at Maine Road.

(6) The Daily Telegraph (19th July, 2013)

The esteem in which Trautmann was held in the blue half of Manchester, and indeed across English football, was all the more remarkable given that he had arrived in Britain 11 years before as a prisoner-of-war - and one regarded by the authorities as a hard-bitten Nazi because of his membership of an elite squad of Luftwaffe paratroops.

Trautmann had in fact lost the zeal that made him a sporting champion in the Hitler Youth after witnessing a massacre of civilians by the SS in occupied Russia, but he remained spiky and competitive. As a PoW he persuaded the camp authorities to let the inmates form a football team, which took on local sides in Lancashire as post-war tensions eased.

He converted from centre half to goalkeeper after taking a knock in one game and refusing to go off. After being signed by non-League St Helen’s Town, in 1949 he went to Manchester City, who were seeking a replacement for the great England international Frank Swift.

The club’s choice, just four years after the war, was controversial, and Trautmann was shocked by the hate mail he received; but the boos and anti-German chants turned to cheers as he excelled on the pitch. He made his mark as a keeper who dominated the penalty area, fearlessly snuffing out threats, instead of staying on his line.

City had reached the 1956 Cup Final - Trautmann’s second - after a series of narrow victories, while their opponents, Birmingham City, had romped to Wembley despite having been drawn away in each round. The Manchester side had also been hit by injury, and were forced to recall their out-of-favour playmaker Don Revie from the reserves.

In the event, Revie proved the match winner - by the 70th minute a string of visionary passes from him had given City a 3-1 lead. But with 16 minutes remaining, Birmingham’s Peter Murphy was presented with a chance.

Out rushed Trautmann (newly voted Footballer of the Year) and, with his customary courage, dived at Murphy’s feet. He succeeded in clutching the ball, but could not prevent his head colliding with Murphy’s leg. Trautmann was left dazed and reeling, but was determined to play on. As he rose to his feet after treatment, the crowd broke into For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow.

At the end of the game, Trautmann was helped up the steps to collect his winner’s medal, all the while rubbing his “stiff neck”. He joined the team on the balcony of Manchester Town Hall as the crowd chanted: “We want Bert!”

Four days later his persistent headache forced him to attend a hospital, where X-rays revealed a fracture. The examining doctor told Trautmann that just one jolt of the bus back from Wembley could have killed him. He was forced to spend five months encased in plaster from head to hips, and thereafter played in a protective cap.

(7) Brian Glanville, The Guardian (19th July, 2013)

When Frank Swift, Manchester City's spectacular England goalkeeper, retired in 1949 after 16 distinguished years between the club's posts, it seemed inconceivable that any keeper could be found to equal him. In the event, an heir was recruited who was perhaps even superior to Swift - and who could have predicted that it would be a former German Luftwaffe paratrooper, only recently out of a prisoner of war camp, and playing for a non-league side in St Helens, a town far better known for its rugby league team? Such, however, was Bert Trautmann, who went on to make 545 appearances over 15 years for City, including an FA Cup final victory in 1956, in which he played the last minutes while suffering from a broken neck. There has scarcely been a better German goalkeeper since than Trautmann, who has died aged 89.

His background was hardly one to endear him to English fans, least of all if, like many of Manchester City's, they happened to be Jewish. Trautmann, who had been a member of the Hitler Youth, was blond and tall, with blue eyes, and looked the very picture of the ideal Aryan. As a paratrooper, he served in Russia, and his eventual autobiography, written with the Manchester Guardian journalist Eric Todd, was called Steppes to Wembley (1957).

Trautmann was born in Bremen, where his father worked in the docks, and he volunteered for the army aged 17. "Growing up in Hitler's Germany, you had no mind of your own," he told Louise Taylor of the Observer in 2010. "You didn't think of the enemy as people at first. Then, when you began taking prisoners, you heard them cry for their mother and father … When you met the enemy, he became a real person."

On the Russian front, as the Nazi forces retreated, Trautmann was blown up but survived. In France, he found himself in a bombed building buried in rubble, but once again lived to tell the tale. He was then taken by American troops and thought he would be shot, but became a prisoner of British forces and ended up in a PoW camp at Ashton-in-Makerfield, in Lancashire.

He acquired English with a Lancashire accent, and played for PoW teams. After the war ended, he declined the offer of repatriation. When City signed him from St Helens Town, their need had been exacerbated by the fact that Alec Thurlow, Swift's understudy, was ill with tuberculosis.

After Trautmann's arrival in Manchester, there were strong protests from Jewish groups, but the city's communal rabbi came out in Trautmann's favour. In very little time, Trautmann had the fans on his side as well. Not only was he big, strong and brave, he was also as friendly towards them as Swift had been.

Because he was playing in England, the Germans never capped Trautmann. They did ultimately make use of him, however, as a liaison man, on the occasion of the 1966 World Cup in England. They might even have won the final had Trautmann been in goal, in the stadium where he had played two consecutive FA Cup finals, in 1955 and 1956.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

References

(1) The Daily Telegraph (19th July, 2013)

(2) Alan Rowlands, Trautmann: The Biography (2011) page 11

(3) Simon Taylor, Revolution, Counter-Revolution and the Rise of Hitler (1983) page 40

(4) Catrine Clay, Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010) page 10

(5) Alan Rowlands, Trautmann: The Biography (2011) page 11

(6) Catrine Clay, Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010) page 16

(7) William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of Nazi Germany (1959) page 252

(8) Louis L. Snyder, Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (1998) page 64

(9) Alan Rowlands, Trautmann: The Biography (2011) page 15

(10) Catrine Clay, Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010) page 20

(11) Richard Evans, The Third Reich in Power (2005) page 272

(12) The Daily Telegraph (19th July, 2013)

(13) Catrine Clay, Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010) pages 25-26

(14) Martyn Housden, Resistance and Conformity in the Third Reich (1996) page 68

(15) Erwin Hammel, interviewed by the authors of What We Knew: Terror, Mass Murder and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany (2005) page 163

(16) Louis L. Snyder, Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (1998) page 162

(17) Alan Rowlands, Trautmann: The Biography (2011) page 20

(18) Louise Taylor, The Guardian (11th April 2010)

(19) Catrine Clay, Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010) page 28

(20) Alan Rowlands, Trautmann: The Biography (2011) page 20

(21) Catrine Clay, Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010) page 22

(22) Cate Haste, Nazi Women (2001) page 101

(23) Louis L. Snyder, Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (1998) page 79

(24) Catrine Clay, Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010) page 50

(25) Alan Rowlands, Trautmann: The Biography (2011) page 25

(26) James Taylor and Warren Shaw, Dictionary of the Third Reich (1987) page 67

(27) Louis L. Snyder, Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (1998) page 201

(28) Catrine Clay, Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010) page 58

(29) Alan Rowlands, Trautmann: The Biography (2011) page 25

(30) Catrine Clay, Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010) page 78

(31) Ivan Ponting, The Independent (19th July, 2013)

(32) Catrine Clay, Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010) page 68

(33) Louise Taylor, The Guardian (11th April 2010)

(34) The Daily Telegraph (19th July, 2013)

(35) Alan Rowlands, Trautmann: The Biography (2011) page 38

(36) The Daily Telegraph (19th July, 2013)

(37) Catrine Clay, Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010) pages 107-108

(38) Alan Rowlands, Trautmann: The Biography (2011) page 41

(39) Louise Taylor, The Guardian (11th April 2010)

(40) Catrine Clay, Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010) page 118

(41) General Heinz Guderian, letter to his wife (10th December, 1941)

(42) Adolf Hitler, military directive (22nd July, 1941)

(43) Louise Taylor, The Guardian (11th April 2010)

(44) Louis L. Snyder, Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (1998) page 267

(45) William L. Shirer, the author of The Rise and Fall of Nazi Germany (1959) page 1106

(46) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) page 690

(47) Alan Rowlands, Trautmann: The Biography (2011) page 50

(48) The Daily Telegraph (19th July, 2013)

(49) Louise Taylor, The Guardian (11th April 2010)

(50) Catrine Clay, Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010) pages 190-195

(51) Ivan Ponting, The Independent (19th July, 2013)

(52) Alan Rowlands, Trautmann: The Biography (2011) page 61

(53) Catrine Clay, Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010) pages 198-199

(54) Louise Taylor, The Guardian (11th April 2010)

(55) Catrine Clay, Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010) pages 206-208

(56) Alan Rowlands, Trautmann: The Biography (2011) page 70

(57) Alan Rowlands, Trautmann: The Biography (2011) page 76

(58) Brian Glanville, The Guardian (19th July, 2013)

(59) Ivan Ponting, The Independent (19th July, 2013)

(60) Alan Rowlands, Trautmann: The Biography (2011) pages 88-89

(61) Alan Rowlands, Trautmann: The Biography (2011) page 91

(62) Catrine Clay, Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010) pages 274-276

(63) Louise Taylor, The Guardian (11th April 2010)

(64) Alan Rowlands, Trautmann: The Biography (2011) page 93

(65) Catrine Clay, Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010) page 277

(66) Ivan Ponting, The Independent (19th July, 2013)

(67) Catrine Clay, Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010) page 280

(68) Glen Isherwood, Wembley: The Complete Record (2006) page 64

(69) Alan Rowlands, Trautmann: The Biography (2011) pages 136-139

(70) Catrine Clay, Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010) page 296

(71) Alan Rowlands, Trautmann: The Biography (2011) page 148

(72) Frank Swift, News of the World (6th May, 1956)

(73) Brian Glanville, The Guardian (19th July, 2013)

(74) The Daily Mirror (7th May, 1956)

(75) Eric Thornton, Manchester Evening News (7th May, 1956)

(76) Ivan Ponting, The Independent (19th July, 2013)

(77) The Daily Telegraph (19th July, 2013)

(78) Catrine Clay, Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010) page 303

(79) Alan Rowlands, Trautmann: The Biography (2011) page 157

(80) Catrine Clay, Trautmann's Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend (2010) page 303

(81) Louise Taylor, The Guardian (11th April 2010)

(82) Ivan Ponting, The Independent (19th July, 2013)

(83) The Daily Telegraph (19th July, 2013)

(84) Louise Taylor, The Guardian (11th April 2010)

(85) The Daily Telegraph (19th July, 2013)