Erwin Hammel

Erwin Hammel, the son of a salesman, was born in Cologne, in 1924. He came from a strong Catholic family who did not support Adolf Hitler. "At home we talked relatively seldom about the politics and the Nazi state. My father was not in the party... My mother was very religious and was certainly not in favour of National Socialism. Therefore, at home, we never really discussed politics. Partly this was because we had a certain amount of fear. One had to be cautious. The next-door neighbor could be someone who was deeply involved in the party and might pass on what he heard. The danger was always there - just don't say too much so that nobody got into trouble."

Hammel was educated at a monastery school. "This was basically a boarding school, and it was more or less cut off from the outside world. So, in effect, we knew little about what was happening on the outside... As children, we didn't have the opportunity to travel, so we didn't get to know Germany from another point of view. We didn't have that at all. This made the propaganda that we were exposed to seem very plausible. We heard and saw nothing else. People today can't imagine this at all. Freedom was whittled away one slice at a time, so that in effect there was no real possibility of a serious revolt. Everything was forced into line. We didn't have the opportunity to hear about the world abroad. There were no foreign newspapers, and so on. Today you can go to any kiosk and buy an American or English newspaper, or a Polish one or whatever, and you can read what others think about us. But back then we didn't have any such opportunity." (1)

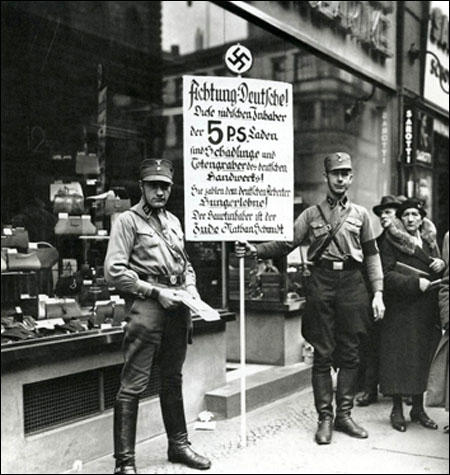

Nazi Boycott of Jewish Shops

Once in power Adolf Hitler began to openly express anti-Semitic ideas. Hitler attempted to make life so unpleasant for Jews in Germany that they would emigrate. The day after the March, 1933, election, stormtroopers hunted down Jews in Berlin and gave them savage beatings. Synagogues were trashed and all over Germany gangs of brownshirts attacked Jews. In the first three months of Hitler rule, over forty Jews were murdered. (2)

The campaign started on 1st April, 1933, when a one-day boycott of Jewish-owned shops took place. Members of the Sturm Abteilung (SA) picketed the shops to ensure the boycott was successful. As a child Christa Wolf watched the SA organize the boycott of Jewish businesses. "A pair of SA men stood outside the door of the house, next to the white enamel plate, and prevented anyone who could not prove that he lived in the building from entering and baring his Aryan body before non-Aryan eyes." (3)

the German economy and pay their German employees starvation wages.

The main owner is the Jew Nathan Schmidt.” (1st April, 1933)

Armin Hertz was only nine years old at the time of the boycott. His parents owned a furniture store in Berlin. "After Hitler came to power, there was the boycott in April of that year. I remember that very vividly because I saw the Nazi Party members in their brown uniforms and armbands standing in front of our store with signs: "Kauft nicht bei Juden" (Don't buy from Jews). That of course, was very frightening to us. Nobody entered the shop. As a matter of fact, there was a competitor across the street - she must have been a member of the Nazi Party already by then - who used to come over and chase people away." (4)

Erwin Hammel later recalled how the Brownshirts stood outside Jewish shops in Cologne carrying signs saying "Germans! Don't buy from Jews!" His only Jewish friend was Max Berkowitz. "The Jews weren't allowed to enter restaurants and so on. I still remember how my father had soon got into trouble, because he had gone into a bar with Herr Berkowitz, the father of my schoolmate Max." (5)

Hitler Youth

In 1940 Erwin Hammel moved to the Three Kings Gymnasium. He was told that if he decided to remain in the school he would have to join the Hitler Youth. "On Saturdays the Hitler Youth had to report for duty and thus they didn't have to go to school. But those who weren't in the Hitler Youth had to go to school and on Saturdays we had shop classes. It is interesting that sometimes the Hitler Youth leader had to come to the school to fetch his Hitler Youth members because they suddenly preferred school to the Hitler Youth."

Erwin Hammel pointed out: "Special youth groups were founded - for example, the Hitler Youth Flyers... Also there was the National Socialist Motor Vehicle Operators Corps (NSKK), which drove motor-cycles... I got into the Naval Hitler Youth, and that was basically more interesting to us because we could cruise the Rhine and didn't have to march along the streets and bellow songs and such things like the regular Hitler Youth." (6)

Second World War

Hammel admits that he enjoyed the early months of the Second World War. "In the first years there was considerable enthusiasm among the population whenever the radio announced special reports on military successes... In general, we had the feeling that we had been attacked and we had to defend ourselves. We even thought that, as Germans, we were invincible. That was the feeling back then... We felt like members of the master race." (7)

In 1942 Erwin Hammel joined the 116th Armoured Division and served under General Gerhard von Schwerin. "I was first in Russia. Later, after the second deployment, I went over to the west. I was in a unit where one respected his opponent as a soldier. This was the case even as far as the officer corps was concerned. We didn't follow the principle of take no prisoners and the like. To the contrary. I still remember one incident when we captured a wounded American. He had a bullet lodged in his body. I went with him to the first aid station, and the medic there didn't want to bandage him. For the medic, he was the enemy. I then made a real fuss about this. In our unit, we didn't stand that kind of behavior." (8)

Erwin Hammel admitted that he was aware of concentration camps. "You knew there were concentration camps. What they looked like from the inside, you didn't know. The first thing I halfway knew about, once I started to perk up my ears, was in Bielitz, where I was in a military hospital. Bielitz-Schielitz had originally been German territory, but it became part of Poland after World War I. In our room, we had a guy of whom it was said, That guy was in a concentration camp. He then said to us, Don't ever ask me about how it was there. I don't want to go back there again, and I'm not allowed to say anything about it. I then basically said to myself, Don't ask. Don't get him into any kind of trouble. He has his reasons for not wanting to go back there. That must have been awful for him. That was the impression I had. That was the first I ever heard about that and the first time I realized that not everything was in order in that regard. On another occasion back then, another guy said to me, Hey, it's stinking here of smoke again. They're burning people again. But it didn't occur to anybody that those who were being burned had been killed in large numbers. Instead, you had thought, Oh well, they must have died of an illness or something like that. Of course, malnutrition and disease were all over the place." (9)

Primary Sources

(1) Erwin Hammel, What We Knew: Terror, Mass Murder and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany (2005)

At home we talked relatively seldom about politics and the Nazi state. My father was not in the party; he was a salesman and he had a printing press and basically stayed out of politics. My mother was very religious and was certainly not in favor of National Socialism. Therefore, at home, we never really discussed politics. Partly this was because we had a certain amount of fear. One had to be cautious. The next-door neighbor could be someone who was deeply involved in the party and might pass on what he heard. The danger was always there-just don't say too much so that nobody got into trouble.

As children, we didn't have the opportunity to travel, so we didn't get to know Germany from another point of view. We didn't have that at all. This made the propaganda that we were exposed to seem very plausible. We heard and saw nothing else. People today can't imagine this at all. Freedom was whittled away one slice at a time, so that in effect there was no real possibility of a serious revolt. Everything was forced into line. We didn't have the opportunity to hear about the world abroad. There were no foreign newspapers, and so on. Today you can go to any kiosk and buy an American or English newspaper, or a Polish one or whatever, and you can read what others think about us. But back then we didn't have any such opportunity.

(2) Erwin Hammel, What We Knew: Terror, Mass Murder and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany (2005)

I came here to the Three Kings Gymnasium in 1940. That's when it began to get serious. Soon I was given a choice either to join the Hitler Youth or to leave school. There were only two boys in the whole class who were not in the Hitler Youth - Thomas, who also came from the monastery school, and I...

The Three Kings Gymnasium was known to be not exactly in line with the party and we basically had rather decent teachers there. We didn't experience any reprimands or anything of the kind if someone was not in the party. Nobody paid attention to that. I know now that the rector must have been a party member, but we weren't really aware of it then. On Saturdays the Hitler Youth had to report for duty and thus they didn't have to go to school. But those who weren't in the Hitler Youth had to go to school and on Saturdays we had shop classes. It is interesting that sometimes the Hitler Youth leader had to come to the school to fetch his Hitler Youth members because they suddenly preferred school to the Hitler Youth.

The Catholic youth organizations, schools, and so on were all forced into line. All of a sudden, they were all taken over by the Hitler Youth and National Socialism. They didn't even resist. The free scout movement remained against this for the longest time. But they were slowly nabbed as well. And then the special youth groups were founded-for example, the Hitler Youth Flyerswhen boys showed interest in them. And if you wanted to fly, you didn't ask, "Is that a[political] party? Is that National Socialist?" As a boy, you more likely

(3) Erwin Hammel, What We Knew: Terror, Mass Murder and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany (2005)

When the war began, I joined the 116th Armored Division under the command of Lieutenant General Graf von Schwerin and we had more or less decent officers as well. I was first in Russia. Later, after the second deployment, I went over to the west. I was in a unit where one respected his opponent as a soldier. This was the case even as far as the officer corps was concerned. We didn't follow the principle of take no prisoners and the like. To the contrary. I still remember one incident when we captured a wounded American. He had a bullet lodged in his body. I went with him to the first aid station, and the medic there didn't want to bandage him. For the medic, he was the enemy. I then made a real fuss about this. In our unit, we didn't stand that kind of behavior.

(4) Erwin Hammel, What We Knew: Terror, Mass Murder and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany (2005)

You knew there were concentration camps. What they looked like from the inside, you didn't know. The first thing I halfway knew about, once I started to perk up my ears, was in Bielitz, where I was in a military hospital. Bielitz-Schielitz had originally been German territory, but it became part of Poland after World War I. In our room, we had a guy of whom it was said, "That guy was in a concentration camp." He then said to us, "Don't ever ask me about how it was there. I don't want to go back there again, and I'm not allowed to say anything about it." I then basically said to myself, "Don't ask. Don't get him into any kind of trouble. He has his reasons for not wanting to go back there. That must have been awful for him." That was the impression I had.

That was the first I ever heard about that and the first time I realized that not everything was in order in that regard. On another occasion back then, another guy said to me, "Hey, it's stinking here of smoke again. They're burning people again." But it didn't occur to anybody that those who were being burned had been killed in large numbers. Instead, you had thought, "Oh well, they must have died of an illness or something like that." Of course, malnutrition and disease were all over the place.

I later grew critical when we were here in the Ruhr region and we saw trucks full of corpses that had been shot up during an air raid. This was practically during the last days of the war. That's when I started to take notice. Those couldn't have simply been sick people. What bothered me most was that all the bodies were naked. That something like that had happened, I saw for the first time here in the Ruhr region. In four or five places, independent of one

another, truck trailers had been driven into ditches and so on. The corpses just lay on top of one another in layers. They just lay there in piles. That was the first time I saw something like that.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

The Hitler Youth (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)