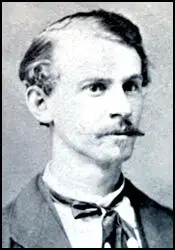

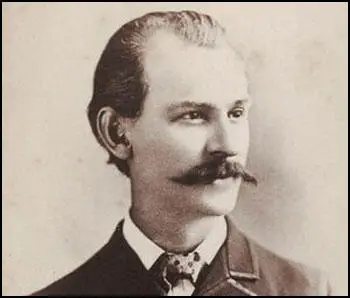

Albert Parsons

Albert Richard Parsons was born in Montgomery, Alabama, on 24th June, 1848. Orphaned at five years old, he was raised by Esther, an African American slave. In the Civil War he served as a member of the Confederate Army under the commanded by his brother, Major General William Parsons.

After the war Parsons condemned slavery and became a Radical Republican. Now a socialist, Parsons began publishing the Spectator, a journal that advocated equal rights for African-Americans.

In 1873 Parsons married Lucy Waller, the daughter of a Creek Indian and a Mexican woman. Mixed marriages in Texas was unacceptable and so under pressure from the Ku Klux Klan, the couple moved to Chicago. Parsons became a printer but after becoming involved in trade union activities he was blacklisted.

Parsons and his wife joined the Socialist Labor Party in 1876. They were also founder members of the International Working Men's Association (the First International), a labor organization that supported racial and sexual equality. Parson also became editor of the radical journal, Alarm.

On 1st May, 1886 a strike was began throughout the United States in support a eight-hour day. Over the next few days over 340,000 men and women withdrew their labor. Over a quarter of these strikers were from Chicago and the employers were so shocked by this show of unity that 45,000 workers in the city were immediately granted a shorter workday.

The campaign for the eight-hour day was organised by the International Working Peoples Association (IWPA). On 3rd May, the IWPA in Chicago held a rally outside the McCormick Harvester Works, where 1,400 workers were on strike. They were joined by 6,000 lumber-shovers, who had also withdrawn their labour. While August Spies, one of the leaders of the IWPA was making a speech, the police arrived and opened-fire on the crowd, killing four of the workers.

The following day August Spies, who was editor of the Arbeiter-Zeitung, published a leaflet in English and German entitled: "Revenge! Workingmen to Arms!". It included the passage: "They killed the poor wretches because they, like you, had the courage to disobey the supreme will of your bosses. They killed them to show you 'Free American Citizens' that you must be satisfied with whatever your bosses condescend to allow you, or you will get killed. If you are men, if you are the sons of your grand sires, who have shed their blood to free you, then you will rise in your might, Hercules, and destroy the hideous monster that seeks to destroy you. To arms we call you, to arms." Spies also published a second leaflet calling for a mass protest at Haymarket Square that evening.

On 4th May, over 3,000 people turned up at the Haymarket meeting. Speeches were made by Parsons, August Spies and Samuel Fielden. At 10 a.m. Captain John Bonfield and 180 policemen arrived on the scene. Bonfield was telling the crowd to "disperse immediately and peacebly" when someone threw a bomb into the police ranks from one of the alleys that led into the square. It exploded killing eight men and wounding sixty-seven others. The police then immediately attacked the crowd. A number of people were killed (the exact number was never disclosed) and over 200 were badly injured.

Several people identified Rudolph Schnaubelt as the man who threw the bomb. He was arrested but was later released without charge. It was later claimed that Schnaubelt was an agent provocateur in the pay of the authorities. After the release of Schnaubelt, the police arrested Samuel Fielden, an Englishman, and six German immigrants, George Engel, August Spies, Adolph Fisher, Louis Lingg, Oscar Neebe, and Michael Schwab. The police also sought Parsons but he went into hiding and was able to avoid capture. However, on the morning of the trial, Parsons arrived in court to standby his comrades.

There were plenty of witnesses who were able to prove that none of the eight men threw the bomb. The authorities therefore decided to charge them with conspiracy to commit murder. The prosecution case was that these men had made speeches and written articles that had encouraged the unnamed man at the Haymarket to throw the bomb at the police.

The jury was chosen by a special bailiff instead of being selected at random. One of those picked was a relative of one of the police victims. Julius Grinnell, the State's Attorney, told the jury: "Convict these men make examples of them, hang them, and you save our institutions."

At the trial it emerged that Andrew Johnson, a detective from the Pinkerton Agency, had infiltrated the group and had been collecting evidence about the men. Johnson claimed that at anarchist meetings these men had talked about using violence. Reporters who had also attended International Working Men's Association meetings also testified that the defendants had talked about using force to "overthrow the system".

During the trial the judge allowed the jury to read speeches and articles by the defendants where they had argued in favour of using violence to obtain political change. The judge then told the jury that if they believed, from the evidence, that these speeches and articles contributed toward the throwing of the bomb, they were justified in finding the defendants guilty.

All the men were found guilty: Parsons, August Spies, Adolph Fisher, Louis Lingg and George Engel were given the death penalty. Whereas Oscar Neebe, Samuel Fielden and Michael Schwab were sentenced to life imprisonment. On 10th November, 1887, Lingg committed suicide by exploding a dynamite cap in his mouth. The following day Parsons, Spies, Fisher and Engel mounted the gallows. As the noose was placed around his neck, Spies shouted out: "There will be a time when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today."

Primary Sources

(1) Albert Parsons, Autobiography of Albert Parsons (1887)

My brother, Major General W. Parsons was in command of the entire cavalry outposts on the west bank of the Mississippi River from Helena to the mouth of the Red River. I was a mere boy of 15 when I joined my brother's command at the front on White River, and was afterward a member of the renowned McInoly scouts under General Parsons' orders, which participated in all the battles of the Curtis, Canby and Banks campaign.

(2) Albert Parsons, speech at his trial (September, 1887)

The labor question is up for settlement. It demands and commands a hearing. The existing disorders threaten not only the peace, but the destruction of society itself. The movement to reduce the work hours is intended by its projectors to give a peaceful solution to the difficulties between capitalists and laborers. I have always held that there were two ways to settle this trouble-either by peaceable or violent methods. Reduced hours- or eight hours - is a peace-offering. It is for capitalists to give or laborers to take. I hold that capitalists will not give eight hours. Why? Because the rate of wages in every wage-paying country is regulated by what it takes to live on; in other words, it is subsistence wages. This subsistence wage is what political economists call the 'iron law of wages', because it is unvarying and inviolable. How does this law operate? In this way: A laborer is hired to do a day's work. In the first two hours of the ten he reproduces the equivalent of his wage; the other eight hours is what the employer gets and gets for nothing. Hence the laborer, as the statistics of the census of 1880 show, does ten work for two hours pay. Now, reduced hours, or eight hours, means that the profit monger is to get only six hours instead of, as now, eight hours for nothing. For this reason employers of labor will not voluntarily concede the reduction. I do not believe that capital will quietly or peaceably permit the economic emancipation of their wage-slaves. It is against all the teachings of history and human nature for men to voluntarily yield up usurped or arbitrary power. The capitalists of the world will for this reason force the workers into armed revolution. Socialists point out this fact and warn the workingmen to prepare for the inevitable.

(3) Albert Parsons, speech at his trial (September, 1887)

My ancestors came to this country a good while ago. My friend Oscar Neebe here is the descendant of a Pennsylvania Dutchman. He and I are the only two who had fortune, or the misfortune, as some people may look at it I don't know and I don't care-to be born in this country. My ancestors had a hand in drawing up and maintaining the Declaration of Independence. My great great grand-uncle lost a hand at the Battle of Bunker Hill. I had a great great great grand-uncle with Washington at Brandywine, Monmouth and Valley Forge. I have been here long enough, I think, to have rights guaranteed at least in the constitution of the country.

(4) Albert Parsons, letter to his wife, Lucy Parson (14th September, 1887)

Our verdict this morning cheers the hearts of tyrants throughout the world, and the result will be celebrated by King Capital in its drunken feast of flowing wine from Chicago to St. Petersburg. Nevertheless, our doom to death is the handwriting on the wall, foretelling the downfall of hate, malice, hypocrisy, judicial murder, oppression, and the domination of man over his fellowman. The oppressed of earth are writhing in their legal chains. The giant Labor is awakening. The masses, aroused from their stupor, will snap their petty chains like reeds in the whirlwind.

We are all creatures of circumstance; we are what we have been made to be. This truth is becoming clearer day by day.

There was no evidence that any one of the eight doomed men knew of, or advised, or abetted the Haymarket tragedy. But what does that matter? The privileged class demands a victim, and we are offered a sacrifice to appease the hungry yells of an infuriated mob of millionaires who will be contented with nothing less than our lives. Monopoly triumphs! Labor in chains ascends the scaffold for having dared to cry out for liberty and right!

Well, my poor, dear wife, I, personally, feel sorry for you and the helpless little babes of our loins.

You I bequeath to the people, a woman of the people. I have one request to make of you: Commit no rash act to yourself when I am gone, but take up the great cause of Socialism where I am compelled to lay it down.

My children - well, their father had better die in the endeavor to secure their liberty and happiness than live contented in a society which condemns nine-tenths of its children to a life of wage slavery and poverty. Bless them; I love them unspeakably, my poor helpless little ones.

Ah, wife, living or dead, we are as one. For you my affection is everlasting. For the people. Humanity. I cry out again and again in the doomed victim's cell: Liberty! Justice! Equality!

(5) The Chicago Daily News, report on the execution of Albert Parsons, August Spies, Adolph Fischer and George Engel (12th November, 1887)

Seldom, if ever, have four men died more gamely and defiantly than the four who were strangled today. Every eye was bent upon the metallic angle around which the four wretched victims were expected to make their appearance. A moment later their curiosity was rewarded. With steady, unfaltering step a white-robed figure stepped out from behind the protecting metallic screen and stood upon the drop. It was August Spies. It was evident that his hands were firmly bound behind him underneath his snowy shroud.

He walked with a firm, almost stately tread across the platform and took his stand under the left-hand noose at the corner of the scaffold farthest from the side at which he had entered. Very pale was the expressive face, and a solemn, far-away light shone in his blue eyes. Nothing could be imagined more melancholy, and at the same time dignified, than the expression which sat upon the face of August Spies at that moment.

Last came Parsons. His face looked actually handsome, though it was very pale. When he stepped upon the gallows he turned partially sideways to the dangling noose and regarded it with a fixed, stony gaze - one of mingled surprise and curiosity. Then he straightened himself under the fourth noose, and, as he did so, he turned his big gray eyes upon the crowd below with such as look of awful reproach and sadness as could not fail to strike the innermost chord of the hardest heart there. It was a look never to be forgotten. There was an expression almost of inspiration on the white, calm face, and the great, stony eyes seemed to burn into men's hearts and ask: "What have I done?"