Leon Czolgosz

Leon Czolgosz, the son of Polish-Russian immigrants, was born in Detroit, Michigan, in 1873. His parents had six other children and in 1881 it was decided to move to a small farm near Cleveland in 1881. Czolgosz found work in a wire mill but in 1898 he suffered a mental breakdown and returned to the family farm.

Czolgosz rejected his family's Roman Catholic beliefs and in 1900 became excited by the news that the Italian immigrant, Gaetano Bresci, had returned to Italy and assassinated King Umberto. He kept newspapers cuttings of the assassination and started to read anarchist newspapers.

On May 6, 1901, Czolgosz travelled to Cleveland to hear Emma Goldman make a speech at the Federal Liberal Club. Afterwards Czolgosz spoke briefly to Goldman. He also followed her back to Chicago and attended other meetings where she made speeches on anarchism. Abraham Isaak became convinced that Czolgosz was a spy and issued a warning about him in his journal, the Free Society.

While in Chicago Czolgosz read that President William McKinley was planning to visit the Pan American Exposition in Buffalo. On 3rd September Czolgosz bought a pistol and two days later was in the audience when McKinley gave a speech at the Temple of Music. Although surrounded by fifty bodyguards, Czolgosz was able to walk up to McKinley and fire two shots at him. Hit in the chest and abdomen, McKinley shouted out "Be easy with him, boys" as secret service agents beat Czolgosz with fists and pistol butts.

William McKinley in September, 1900.

William McKinley was taken to hospital where it was discovered that the chest wound was superficial but the other bullet had torn through the stomach wall. For the first few days his condition improved and newspapers reported that he would recover. However, the path of the bullet that had passed through the wall of the stomach and his kidney, had turned gangrenous and he died on the 14th September, 1901.

When questioned Czolgosz claimed he had been incited to kill McKinley by the speeches of Emma Goldman. She was arrested and imprisoned for questioning. When she was finally released she shocked the public by stating that: "He (Czolgosz) had committed the act for no personal reasons or gain. He did it for what is his ideal: the good of the people. That is why my sympathies are with him." However, as Bill Falkowski pointed out: "He (Czolgosz) was roundly denounced by spokespersons of the Left, with the lone sympathetic exception of Emma Goldman, who nonetheless advised against individual acts of political violence."

Leon Czolgosz was tried and found guilty of killing McKinley. Before being executed on 20th October, 1901, Czolgosz remarked that: "I killed the President because he was the enemy of the good people - the good working people. I am not sorry for my crime."

Primary Sources

(1) In her autobiography, Living My Life, Emma Goldman described her two meetings with Leon Czolgosz who at the time was using the name Nieman.

The subject of my lecture in Cleveland, early in May of that year, was Anarchism, delivered before the Franklin Liberal Club, a radical organization. During the intermission before the discussion I noticed a man looking over the titles of the pamphlets and books on sale near the platform. Presently he came over to me with the question: "Will you suggest something for me to read?" He was working in Akron, he explained, and he would have to leave before the close of the meeting. He was very young, a mere youth, of medium height, well built, and carrying himself very erect. But it was his face that held me, a most sensitive face, with a delicate pink complexion; a handsome face, made doubly so by his curly golden hair. Strength showed in his large blue eyes. I made a selection of some books for him, remarking that I hoped he would find in them what he was seeking. I returned to the platform to open the discussion and I did not see the young man again that evening, but his striking face remained in my memory.

The Isaaks had moved Free Society to Chicago, where they occupied a large house which was the centre of the anarchist activities in that city. On my arrival there, I went to their home and immediately plunged into intense work that lasted eleven weeks. The summer heat became so oppressive that the rest of my tour had to be postponed until September. I was completely exhausted and badly in need of rest. Sister Helena had repeatedly asked me to come to her for a month, but I had not been able to spare the time before. Now was my opportunity. I would have a few weeks with Helena, the children of my two sisters, and Yegor, who was spending his vacation in Rochester.

On the day of our departure the Isaaks gave me a farewell luncheon. Afterwards, while I was busy packing my things, someone rang the bell. Mary Isaak came in to tell me that a young man, who gave his name as Nieman, was urgently asking to see me. I knew nobody by that name and I was in a hurry, about to leave for the station. Rather impatiently I requested Mary to inform the caller that I had no time at the moment, but that he could talk to me on my way to the station. As I left the house, I saw the visitor, recognizing him as the handsome chap who had asked me to recommend him reading matter at the Cleveland meeting.

Hanging on to the straps on the elevated train, Nieman told me that he had belonged to a Socialist local in Cleveland, that he had found its members dull, lacking in vision and enthusiasm. He could not bear to be with them and he had left Cleveland and was now working in Chicago and eager to get in touch with anarchists.

(2) Abraham Isaak, the editor of the anarchist journal, Free Society, issued a warning that he believed Leon Czolgosz was a spy.

The attention of the comrades is called to another spy. He is well dressed, of medium height, rather narrow shouldered, blond, and about 25 years of age. Up to the present he has made his appearance in Chicago and Cleveland. In the former place he remained a short time, while in Cleveland he disappeared when the comrades had confirmed themselves of his identity and were on the point interested in the cause, asking for names, or soliciting aid for acts of contemplated violence. If this individual makes his appearance elsewhere, the comrades are warned in advance and can act accordingly.

(3) The Wichita Daily Eagle (7th September, 1901)

It was shortly after 4 p.m. when one of the throng which surrounded the presidential party, a medium sized man of ordinary appearance and plainly dressed in black, approached as if to greet the president. He worked his way amid the stream of people until he was within two feet of the president.

President McKinley smiled, bowed and extended his hand in the spirit of congeniality his American people so well know, when suddenly the sharp crack of a revolver rang out loud and clear above the hum of the voices, the shuffling of myriad feet and vibrating waves of applause.

There was an instance of almost complete silence. The president stood stood still, a look of hesitancy, almost of bewilderment on his face. Then he retreated a step, while a pallor began to steal over his features.

Then came a commotion. Three men threw themselves forward, as with one impulse, and sprang toward the would-be assassin. Two of them were United States secret service men who were on the lookout, and whose duty it was to guard against such a calamity. The third was a by-stander, a negro, who had only an instant previously grasped the hand of the president. In a twinkling the assassin was borne to the ground, his weapon was wrestled from his grasp, and strong arms pinioned him down.

(4) The New York Times (8th September, 1901)

All the official bulletins showed great gains and inspired those near the President to state positively that he would recover rapidly. The strain on the heartstrings of the Nation has been relieved.

(5) Jane Addams, Twenty Years at Hull House (1910)

It is impossible to overstate the public excitement of the moment and the unfathomable sense of horror with which the community regarded an attack upon the chief executive of the nation, as a crime against government itself which compels an instinctive recoil from all law-abiding citizens. Both the hatred and the determination to punish reached the highest pitch in Chicago.

It seemed to me then that in the millions of words uttered and written at that time, no one adequately urged that public-spirited citizens set themselves the task of patiently discovering how these sporadic acts of violence against government may be understood and averted. We do not know whether they occur among the discouraged and unassimilated immigrants who might be cared for in such a way as enormously to lessen the probability of these acts, or whether they are the result of anarchistic teaching.

As the details of the meager life of the President's assassin were disclosed, they were a challenge to the forces for social betterment in American cities. Was it not an indictment to all those whose business it is to interpret and solace the wretched, that a boy should have grown up in an American city so uncared for, so untouched by higher issues, his wounds of life so unhealed by religion that the first talk he ever heard dealing with life's wrongs, although anarchistic and violent, should yet appear to point a way of relief?

(6) Alice Hamilton, Exploring the Dangerous Trades (1943)

Prince Peter Kropotkin was one of the most lovable persons I have ever met. He was a typical revolutionist of the early Russian type, an aristocrat who threw himself into the movement for emancipation of the masses out of a passionate love for his fellow man, and a longing for justice.

He stayed some time with us at Hull House, and we all came to love him, not only we who lived under the same roof but the crowds of Russian refugees who came to see him. No matter how down-and-out, how squalid even, a caller would be., Prince Kropotkin would give him a joyful welcome and kiss him on both cheeks.

It was most unfortunate that his visit to us came just a short time before the assassination of McKinley. That event woke up the dormant terror of anarchists which always lay close under the surface of Chicago's thinking and feeling, ever since the Haymarket riot. It was known that Czolgosz, the assassin, had been in Chicago at the time when both Emma Goldman and Kropotkin were there, and a rumor started that he had met them and the plot had been of their making - Czolgosz had been their tool. Then the story came to involve Hull House, which had been the scene of these secret, murderous meetings.

(7) In her autobiography, Living My Life, Emma Goldman described being arrested after the assassination of William McKinley.

Some of the reporters did not seem to be losing sleep over the case. One of them was quite amazed when I assured film that in my professional capacity I would take care of McKinley if I were called upon to nurse him, though my sympathies were with Czolgosz." You're a puzzle, Emma Goldman," he said, "I can't understand you. You sympathize with Czolgosz, yet you would nurse the man he tried to kill." "As a reporter you aren't expected to understand human complexities," I informed him. "Now listen and see if you can get it. The boy in Buffalo is a creature at bay. Millions of people are ready to spring on him and tear him limb from limb. He committed the act for no personal reasons or gain. He did it for what is his ideal: the good of the people. That is why my sympathies are with him. On the other hand," I continued, "William McKinley, suffering and probably near death, is merely a human being to me now. That is why I would nurse him."

"I don't get you, you're beyond me," he reiterated. The next day there appeared these headlines in one of the papers: "EMMA GOLDMAN WANTS TO NURSE PRESIDENT; SYMPATHIES ARE WITH SLAYER." Buffalo failed to produce evidence to justify my extradition. Chicago was getting weary of the game of hide-and-seek. The authorities would not turn me over to Buffalo, yet at the same time they did not feel like letting me go entirely free. By way of compromise I was put under twenty-thousand-dollar bail. The Isaak group had been put under fifteen-thousand-dollar bail. I knew that it would be almost impossible for our people to raise a total of thirty-five thousand dollars within a few days. I insisted on the others being bailed out first. Thereupon I was transferred to the Cook County Jail.

The night before my transfer was Sunday. My saloon-keeper admirer kept his word; he sent over a huge tray filled with numerous goodies: a big turkey, with all the trimmings, including wine and flowers. A note came with it informing me that he was willing to put up five thousand dollars towards my bail. "A strange saloon-keeper!" I remarked to the matron. "Not at all," she replied; "he's the ward heeler and he hates the Republicans worse than the devil." I invited her, my two policemen, and several other officers present to join me in the celebration. They assured me that nothing like it had ever before happened to them - a prisoner playing host to her keepers. "You mean a dangerous anarchist having as guests the guardians of law and order," I corrected. When everybody had left, I noticed that my day watchman lingered behind. I inquired whether he had been changed to night duty. " No," he replied, " I just wanted to tell you that you are not the first anarchist I've been assigned to watch. I was on duty when Parsons and his comrades were in here."

Peculiar and inexplicable the ways of life, intricate the chain of events! Here I was, the spiritual child of those men, imprisoned in the city that had taken their lives, in the same jail, even under the guardianship of the very man who had kept watch in their silent hours. Tomorrow I should be taken to Cook County Jail, within whose walls Parsons, Spies, Engel, and Fischer had been hanged. Strange, indeed, the complex forces that had bound me to those martyrs through all my socially conscious years! And now events were bringing me nearer and nearer - perhaps to a similar end?

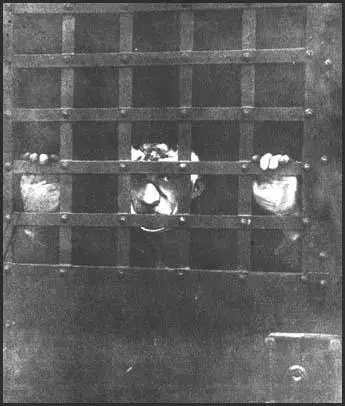

The newspapers had published rumours about mobs ready to attack the Harrison Street Station and planning violence to Emma Goldman before she could be taken to the Cook County Jail. Monday morning, flanked by a heavily armed guard, I was led out of the station-house. There were not a dozen people in sight, mostly curiosity seekers. As usual, the press had deliberately tried to incite a riot.

Ahead of me were two handcuffed prisoners roughly hustled about by the officers. When we reached the patrol wagon, surrounded by more police, their guns ready for action, I found myself close to the two men. Their features could not be distinguished: their heads were bound up in bandages, leaving only their eyes free. As they stepped to the patrol wagon, a policeman hit one of them on the head with his club, at the same time pushing the other prisoner violently into the wagon. They fell over each other, one of them shrieking with pain. I got in next, then turned to the officer. "You brute," I said, "how dare you beat that helpless fellow?" The next thing I knew, I was sent reeling to the floor. He had landed his fist on my jaw, knocking out a tooth and covering my face with blood. Then he pulled me up, shoved me into the seat, and yelled: "Another word from you, you damned anarchist, and I'll break every bone in your body!"