Mollie Steimer

Mollie Steimer was born in Dunaevtsky, Russia, on 21st November, 1897. When she was fifteen her family emigrated to the United States and settled in New York City.

Steimer found work in a garment factory and soon became involved in trade union activities. This led to her reading books on politics including Women and Socialism (August Bebel), Statehood and Anarchy (Mikhail Bakunin), Memoirs of a Revolutionist (Peter Kropotkin) and Anarchism and Other Essays (Emma Goldman).

In 1917 Steimer joined the Freiheit, a group of Jewish anarchists based in New York City, that had been formed by Johann Most. Steimer shared a six-room apartment at 5 East 104th Street in Harlem with members of the group. This also became the place where the Freiheit held its meetings and published its newspaper. Other members included Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman. Some of the younger members, including Steimer, formed a new group called Frayhayt (Freedom) and launched a new journal with the same name. She persuaded Robert Minor to produce some cartoons for the journal.

The Frayhayt group were opposed to the United States becoming involved in the First World War. On the masthead of their newspaper contained the words: "The only just war is the social revolution". After the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, Congress passed the Espionage Act, making it an offence to publish material that undermined the war effort.

Steimer was furious when she heard the news that the United States Army had invaded Russia after the Bolshevik government signed the Brest-Litovsk Treaty. She produced two leaflets, one in English and one in Yiddish, appealing to American workers to launch a general strike. "Will you allow the Russian Revolution to be crushed? You; yes, we mean you, the people of America! The Russian Revolution calls to the workers of the world for help... Yes, friends, there is only one enemy of the workers of the world and that is capitalism."

An estimated 10,000 leaflets were distributed in New York City before Mollie Steimer, Jacob Abrams, Hyman Lachowsky, Samuel Lipman, Jacob Schwartz and Gabriel Prober were arrested on 23rd August, 1918, for publishing material that undermined the American war effort. The men were beaten in prison and Schwartz died before he could be brought to court. At his funeral, John Reed and Alexander Berkman made speeches to a gathering of 1,200 mourners.

The trial began on 10th October, 1918, at the Federal Court House in New York City. During the proceedings, the 20 year old Steimer explained her anarchist beliefs: "Anarchism is a new social order where no group shall be governed by another group of people. Individual freedom shall prevail in the full sense of the word. Private ownership shall be abolished. Every person shall have an equal opportunity to develop himself well, both mentally and physically. We shall not have to struggle for our daily existence as we do now. No one shall live on the product of others. Every person shall produce as much as he can, and enjoy as much as he needs - receive according to his need. Instead of striving to get money, we shall strive towards education, towards knowledge. While at present the people of the world are divided into various groups, calling themselves nations, while one nation defies another - in most cases considers the others as competitive - we, the workers of the world, shall stretch out our hands towards each other with brotherly love. To the fulfillment of this idea I shall devote all my energy, and, if necessary, render my life for it."

Steimer was found guilty of breaking the Espionage Act and was sentenced to fifteen years and a $500 fine. Jacob Abrams, Hyman Lachowsky and Samuel Lipman got twenty years and a $1,000 fine. Gabriel Prober, who had been arrested by mistake, was cleared of all charges. Zechariah Chafee of the Harvard Law School led the protests against the severity of the sentences. He pointed out had been convicted solely for advocating non-intervention in the affairs of another nation: "After priding ourselves for over a century on being an asylum for the oppressed of all nations, we ought not suddenly jump to the position that we are only an asylum for men who are no more radical than ourselves."

Others who joined in the protests included Felix Frankfurter, Norman Thomas, Roger Baldwin, Margaret Sanger, Lincoln Steffens, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Hutchins Hapgood, Leonard Dalton Abbott, Alice Stone Blackwell, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Neith Boyce. A group, the League of Amnesty of Political Prisoners was formed and it published a leaflet on the case, Is Opinion a Crime? Steimer and the the other three anarchists were released on bail to await the results of their appeal.

Over the next few months Steimer was arrested seven times but after being held in various prisons was always released without charge. Agnes Smedley was one of those who met her in prison: "Mollie Steimer championed the cause of the prisoners - the one with venereal disease, the mother with diseased babies, the prostitute, the feeble-minded, the burglar, the murderer. To her they were but products of a diseased social system. She did not complain that even the most vicious of them were sentenced to no more than 5 or 7 years, while she herself was facing 15 years in prison."

Emma Goldman complained that: "The entire machinery of the United States government was being employed to crush this slip of a girl weighing less than eighty pounds." On the 30th October, 1919, she was arrested she was taken to Blackwell Island. While in prison the Supreme Court upheld her conviction under the Espionage Act. However, two justices, Louis Brandeis and Oliver Wendell Holmes, issued a strong dissenting opinion. Steimer was now transferred to the Jefferson City Prison in Missouri.

During this period A. Mitchell Palmer, the attorney general and his special assistant, John Edgar Hoover, used the Sedition Act to launch a campaign against radicals and their organizations. Using this legislation it was decided to remove immigrants who had been involved in left-wing politics. This included Steimer, Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman and 245 other people who were deported to Russia. A fellow anarchist, Marcus Graham, wrote: "In Russia their activity is yet more needed. For there, a government rules masquerading under the name of the proletariat and doing everything imaginable to enslave the proletariat."

Deported to Russia on the Estonia, Steimer arrived in Moscow on 15th December, 1921. Over the next few months she worked closely with Vsevolod Volin, the editor of the Golos Truda, a journal published in Petrograd. She was also a member of the the Nabat Confederation of Anarchist Organizations. The Bolshevik government hated anarchists and she soon became a target for the Russian Secret Police.

On 1st November, 1922 she was arrested with her boyfriend, Senya Fleshin and charged with aiding criminal elements in Russia. Sentenced to two years in Siberia, Steimer managed to escape and return to Moscow where she worked for the Society to Help Anarchist Prisoners. She was soon arrested and on 27th September she was deported to Germany where she joined Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman in Berlin.

Steimer began contributing articles for anarchist journals in Europe. In one article published in January 1924 she argued that in Russia, a great popular revolution had been usurped by a ruthless political elite: "No, I am not happy to be out of Russia. I would rather be there helping the workers combat the tyrannical deeds of the hypo-critical Communists."

Steimer and Senya Fleshin moved to Paris and joined a group of anarchist exiles that included Nestor Makhno, Peter Arshinov, Vsevolod Volin, Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, Alexander Schapiro, Sébastien Faure, Jacques Doubinsky and Rudolf Rocker. They formed the Joint Committee for the Defense of Revolutionaries Imprisoned in Russia. In 1926 they established the Relief Fund of the International Working Men's Association for Anarchism and Anarcho-Syndicalists Imprisoned in Russia.

Emma Goldman sometimes clashed with Steimer: "Mollie Steimer is a fanatic to the highest degree... She is terribly sectarian, set in her notions, and has an iron will. No ten horses could drag her from anything she is for or against. But with it all she is one of the most genuinely devoted souls living with the fire of our ideal."

In 1926 Nestor Makhno joined forces broke with Peter Arshinov to publish their controversial Organizational Platform, which called for a General Union of Anarchists. This was opposed by Steimer, Senya Fleshin, Emma Goldman, Vsevolod Volin, Alexander Berkman, Sébastien Faure and Rudolf Rocker, who argued that the idea of a central committee clashed with the basic anarchist principle of local organisation. In November 1927 Steimer wrote: "The entire spirit of the platform is penetrated with the idea that the masses must be politically led during the revolution. There is where the evil starts."

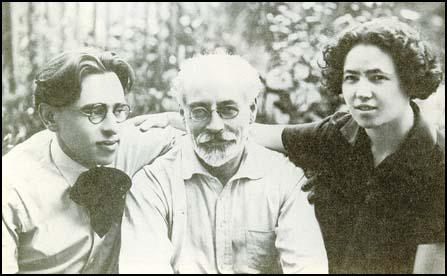

Senya Fleshin took up photography. As Paul Avrich has pointed out: "In order to earn a living, Senya had meanwhile taken up the profession of photography, for which he exhibited a remarkable talent; he became the Nadar of the anarchist movement, with his portraits of Berkman, Volin, and many other comrades, both well known and obscure, as well as a widely reproduced collage of the international anarchist press."

In 1929 Fleshin was invited to work in the studio of Sasha Stone in Berlin. Steimer went with him and they remained there until Adolf Hitler took power. They no longer felt safe in Nazi Germany and they moved back to Paris, where they remained until the Second World War. After the Nazi invasion and the formation of the Vichy government, Steimer and Fleshin decided to go to Mexico. They attempted to persuade Vsevolod Volin to go with them but he refused, claiming he had to stay in France in order to "prepare for the revolution when the war is over."

In Mexico City Steimer and Fleshin operated a successful photographic studio. They retired to Cuernavaca in 1963. As the of Anarchist Portraits (1995) has pointed out: "Fluent in Russian, Yiddish, English, German, French, and Spanish, she corresponded with comrades and kept up with the anarchist press around the world."

Mollie Steimer died in her home following a heart-attack on 23rd July, 1980.

Primary Sources

(1) Molly Steimer, speech made in court during her trial under the Espionage Act (October, 1918)

Anarchism is a new social order where no group shall be governed by another group of people. Individual freedom shall prevail in the full sense of the word. Private ownership shall be abolished. Every person shall have an equal opportunity to develop himself well, both mentally and physically. We shall not have to struggle for our daily existence as we do now. No one shall live on the product of others. Every person shall produce as much as he can, and enjoy as much as he needs - receive according to his need. Instead of striving to get money, we shall strive towards education, towards knowledge.

While at present the people of the world are divided into various groups, calling themselves nations, while one nation defies another - in most cases considers the others as competitive - we, the workers of the world, shall stretch out our hands towards each other with brotherly love. To the fulfillment of this idea I shall devote all my energy, and, if necessary, render my life for it.

(2) Agnes Smedley was imprisoned for distributing birth control leaflets in 1918. While in prison she met Molly Steimer and wrote about her in her book Cell Mates (1920)

Mollie Steimer championed the cause of the prisoners - the one with venereal disease, the mother with diseased babies, the prostitute, the feeble-minded, the burglar, the murderer. To her they were but products of a diseased social system. She did not complain that even the most vicious of them were sentenced to no more than 5 or 7 years, while she herself was facing 15 years in prison. She asked that the girl with venereal disease be taken to a hospital; the prison physician accused her of believing in free love and in Bolshevism. She asked that the vermin be cleaned from the cells of one of the girls; the matron ordered her to attend to her own affairs - that it was not her cell. "Lock me in," she replied to the matron; "I have nothing to lose but my chains."

(3) Emma Goldman, Living My Life (1931)

The Espionage Act resulted in filling the civil and military prisons of the country with men sentenced to incredibly long terms; Bill Haywood received twenty years, his hundred and ten International Workers of the World co-defendants from one to ten, Eugene V. Debs ten years, Kate Richards O'Hare five. These were but a few among the hundreds railroaded to living death. Then came the arrest of a group of our young comrades in New York, comprising Mollie Steimer, Jacob Abrams, Samuel Lipman, Hyman Lachowsky and Jacob Schwartz. Their offence consisted in circulating a printed protest against American intervention in Russia.

(4) Emma Goldman, letter to Alexander Berkman (29th February, 1932)

Mollie Steimer is a fanatic to the highest degree... She is terribly sectarian, set in her notions, and has an iron will. No ten horses could drag her from anything she is for or against. But with it all she is one of the most genuinely devoted souls living with the fire of our ideal.

(5) Paul Avrich, Anarchist Portraits (1990)

For the next twenty years Senya operated his photographic studio in Mexico City under the name SEMO for Senya and Mollie. During this time they formed a close relationship with their Spanish comrades of the Tierra y Libertad group, while remaining on affectionate terms with Jack and Mary Abrams, notwithstanding Jack's friendship with Trotsky, who had joined the colony of exiles in Mexico. Shortly before his death in 1953, Abrams was allowed to enter the United States to have an operation for throat cancer. "He was a dying man who could hardly move," their friend Clara Larsen recalled, "yet he was guarded by an FBI agent twenty-four hours a day!"

Mollie, however, never returned to America. Friends and relatives had to cross the border and visit her in Mexico City or Cuernavaca, to which she and Senya retired in 1963. When deported from the United States, Mollie had vowed to "advocate my ideal, Anarchist Communism, in whatever country I shall be." In Russia, in Germany, in France, and now in Mexico, she remained faithful to her pledge. Fluent in Russian, Yiddish, English, German, French, and Spanish, she corresponded with comrades and kept up with the anarchist press around the world. She also received many visitors, including Rose Pesotta and Clara Larsen from New York.

In 1976 Mollie was filmed by a Dutch television crew working on a documentary about Emma Goldman, and in early 1980 she was filmed again by the Pacific Street Collective of New York, to whom she spoke of her beloved anarchism in glowing terms. In her last years, Mollie felt worn and tired. She was deeply saddened by the death of Mary Abrams in January 1978. Two years later, not long after her interview with Pacific Street films, she collapsed and died of heart failure in her Cuernavaca home. To the end, her revolutionary passion had burned with an undiminished flame. Senya, weak and ailing, was crushed by her sudden passing. Lingering on less than a year, he died in the Spanish Hospital in Mexico City on June 19, 1981.