Joel Barr

Joel Barr, was born in New York City on 1st January, 1916. His parents were Jewish immigrants who had fled from Russia after the failed 1905 Revolution.

According to Alexander Feklissov, "Barr came from an impoverished Jewish family. Upon arriving in New York the Barrs were desperately trying to make ends meet. Once, when they were unable to pay the rent, the police threw them into the street." (1)

Barr and Julius Rosenberg went to the same school and became close friends. They both passed the tough entrance examination to City College of New York where college tuition was free. They also both joined the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA).

The Army Signal Corps Engineering Laboratories at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, hired Barr as an electrical engineer in July 1940. Rosenberg signed on with the corps as a junior engineer two months later. (2) In 1941 they were recruited as Soviet spies by Jacob Golos. Barr's code name was Meter (3). They in turn persuaded Alfred Sarant to join the network.

According to Alexander Feklissov: "Joel and Alfred were good friends and spent a lot of time together. I must admit that Sarant had the makings of an undercover agent; he was a cautious young man, yet full of resolve, with progressive ideas. Before we recruited him though, he had to pass a test. Barr asked Sarant to borrow some secret documents to which he had access because he, Barr, needed them for his personal use. Alfred did not hesitate in helping his friend and in the meantime the Center approved a bona fide approach." (4) However, he was at first reluctant to become a spy but was eventually convinced to join the network by Barr. Sarant was given the code name Hughes.

Steven T. Usdin has pointed out: "Barr recruited Alfred Sarant, the only known member of the Rosenberg ring who was neither Jewish nor a graduate of City College of New York. Barr and Sarant were talented electrical engineers who found technical advances in radar and electronics as compelling and important as class struggle. This dual set of interests made them remarkably successful... Barr and Sarant worked on, or had access to, detailed specifications for most of the US air- and ground-based radars; the Norden bombsight; analog fire-control computers; friend-or-foe identification systems; and a variety of other technologies." (5)

Alexander Feklissov later recalled that Sarant's recruitment had a positive effect on Barr "who no longer felt alone and could sleep better". (6) Sarant even moved to Greenwich Village to share his friend's apartment. Sarant also got a new job at Bell Research Laboratories developing radio electrical devices for military application. This included working on the Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star. Barr worked for the Western Electric plant in New York City, designing improvements on radar devices to be fitted on B-type bombers.

Joel Barr - Soviet Spy

Alexander Feklissov watched the early progress of Barr and Julius Rosenberg: "They shared many interests; they had the same Communist ideals; they were part of of a study group of Marxist literature and sympathized with the USSR... From the start of our relationship we asked them to hide their opinions and refrain from any activity they could draw attention to them." (7)

On 23 February 1942, the Signal Corps fired Barr on the advice of the FBI and placed his name on a list of undesirable employees who were ineligible for employment by the army. "More than 100 of Barr’s colleagues at the Signal Corps laboratory signed petitions requesting that the army reconsider the action; many of them scratched their names off or ripped up the petitions when they learned that he had been fired because he was a communist." (8)

Rosenberg's Spy Network

Rosenberg's spy network included Barr, Alfred Sarant, Morton Sobell, David Greenglass, William Perl and Vivian Glassman. Barr had access to most of the secret documentation available in his field. Barr took the material as he left the office at night. He passed the material to Rosenberg, who arranged for it to be copied by Semyon Semyonov. The material reached Barr before he returned it to the office the following morning. Alexander Feklissov claims that between 1943 and 1945 the Rosenberg group "had given me over 20,000 pages of technical documents plus another 12,000 pages of the complete design manual for the first U.S. jet fighter, the P-80 Shooting Star." (9)

By 1944 Rosenberg was microfilming the documents being stolen by Barr and Sarant, who worked at Bell Research Laboratories developing radio electrical devices for military application. On 5th December, 1944, Stepan Apresyan warned about overworking Rosenberg: "Expedite consent to the joint filming of their materials by both METER (Joel Barr) and HUGHES (Alfred Sarant). LIBERAL (Julius Rosenberg) has on hand eight people plus the filming of materials. The state of LIBERAL's health is nothing splendid. We are afraid of putting LIBERAL out of action with overwork." (10)

The Soviets suffered a set-back when Julius Rosenberg was sacked from the Army Signal Corps Engineering Laboratories at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, when they discovered that he had been a member of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA). NKVD headquarters in Moscow sent Leonid Kvasnikov a message on 23rd February, 1945: "The latest events with (Julius Rosenberg), his having been fired, are highly serious and demand on our part, first, a correct assessment of what happened, and second, a decision about (Rosenberg's) role in future. Deciding the latter, we should proceed from the fact that, in him, we have a man devoted to us, whom we can trust completely, a man who by his practical activities for several years has shown how strong is his desire to help our country. Besides, in (Rosenberg) we have a capable agent who knows how to work with people and has solid experience in recruiting new agents." (11)

Kvasnikov's main concern was that the FBI had discovered that Rosenberg was a spy. To protect the rest of the network, Feklissov was told not to have any contact with Rosenberg. However, the NKVD continued to pay Rosenberg "maintenance" and was warned not to take any important decisions about his future work without their consent. Eventually they gave him permission to take "a job as a radar specialist with Western Electric, designing systems for the B-29 bomber." (12)

Sperry Gyroscope Company

In October 1946 Joel Barr found work at the Sperry Gyroscope Company. He was employed to work on a classified missile defense project and in June 1947, a security official at the company contacted the FBI to ask about a security clearance for their new employee. According to Steven T. Usdin: "The Bureau quickly noted that he had been fired from the army as a subversive and that he was on a list of communist party members. Nonetheless, it spent months collecting documents from the army, interviewing Barr’s neighbors, and peering into his bank accounts. In the first week of October 1947, the Bureau sent a summary of its investigation to Sperry, which fired him a week later. The FBI’s success in finally ending Barr’s espionage career was marred by its failure to exploit the leads generated by his case. The Bureau treated Barr as a security risk but did not seriously investigate the possibility that he was a Soviet spy. On his job application, which Sperry had turned over to the FBI, Barr had listed three personal references. FBI agents interviewed two of them, but inexplicably ignored the third: Julius Rosenberg. If the agents who reviewed Barr’s file had looked, they would have seen that the Bureau had an extensive file on Rosenberg." (13)

Alexander Feklissov explained that it was now important to get Barr out of the country: "He was 32 years old and his chances of securing a job commensurate with his qualifications after such a rejection were basically nil. His love of music took over and since at his age he couldn't hope to become a pianist, he wanted to be a composer. Joel told his new Soviet case officer who was actually only a contact, since he no longer produced any information that he wanted to go to Europe. Even for Soviet intelligence the change in its agent's life was not very attractive, the rule was to help all important sources in their enterprises and to thank them for that they had done in the past. Furthermore, Barr could also become an excellent illegal in the future. Its case officer approved his plan. Out of caution, Joel first went to Belgium, but his destination was Paris. He began by learning to play the piano very well, but he didn't want to go to the Conservatoire because he had his own theory and system. In six months he learned the piano without doing scales, which he hated. He became a pupil of Olivier Messiaen, the famous composer and teacher. The very talented Barr quickly made many friends within international artistic circles." (14)

Arrest of the Rosenberg Group

On 16th June, 1950, David Greenglass was arrested. The New York Tribune quoted him as saying: "I felt it was gross negligence on the part of the United States not to give Russia the information about the atom bomb because he was an ally." (15) According to the New York Times, while waiting to be arraigned, "Greenglass appeared unconcerned, laughing and joking with an FBI agent. When he appeared before Commissioner McDonald... he paid more attention to reporters' notes than to the proceedings." (16) Greenglass's attorney said that he had considered suicide after hearing of Gold's arrest. He was also held on $1000,000 bail.

On 6th July, 1950, the New Mexico federal grand jury indicted Greenglass on a charge of conspiring to commit espionage in wartime on behalf of the Soviet Union. Specifically, he was accused of meeting with Harry Gold in Albuquerque on 3rd June, 1945, and producing "a sketch of a high explosive lens mold" and receiving $500 from Gold. It was clear that Gold had provided the evidence to convict Greenglass.

The New York Daily Mirror reported on 13th July that Greenglass had decided to join Harry Gold and testify against other Soviet spies. "The possibility that alleged atomic spy David Greenglass has decided to tell what he knows about the relay of secret information to Russia was evidenced yesterday when U. S. Commissioner McDonald granted the ex-Army sergeant an adjournment of proceedings to move him to New Mexico for trial." (17) Four days later the FBI announced the arrest of Julius Rosenberg. The New York Times reported that Rosenberg was the "fourth American held as a atom spy". (18)

Joel Barr in Czechoslovakia

NKVD was worried that Joel Barr would be arrested in Paris. It was decided to help him flee to Czechoslovakia: "After the arrest of Gold and David Greenglass, it became clear that he was running the risk of being arrested as well. An escape route was set up. Czechoslovakia was at that time a hub between Western and Eastern Europe. Easily accessible to Westerners, the country was firmly part of the Socialist bloc. His case officer advised him not to request a visa in France since it was a NATO member and an ally of the United States. Barr went to Switzerland, obtained a visa, and on June 22 arrived by train in Prague. He was now safe." (19)

With the help of the intelligence services Barr acquired a new identity, he changed his name to Johan Burgh and became a citizen of South Africa. His birth date was also altered to 7th October, 1917. He was joined by Alfred Sarant, who took the name Philip Staros. His "legend" was that he had been born in Greece and had been living in Canada, which explained his excellent mastery of the English language. Barr married a local Czech woman, Vera Bergova.

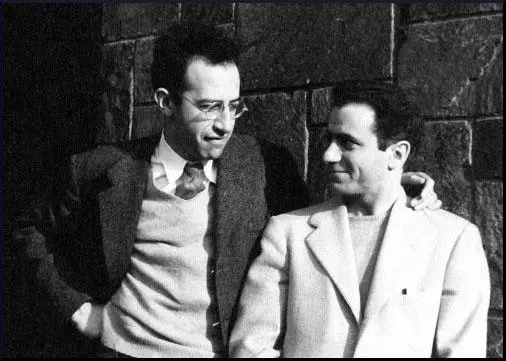

Alexander Feklissov met them in Prague in 1955 to discuss their future: "Sarant... was a handsome southern European type, with black hair slicked back, bushy eyebrows, small mustache and swarthy complexion. His dark eyes were set very deep. I had seen pictures of him smiling and now he appeared dark and unhappy, just like Barr. They both gazed at me intensely. They were, in fact very different types as I could observe during the meal. Alfred was not so tall, about five feet eight, well built, with broad shoulders full of Mediterranean exuberance. Joel Barr looked like an intellectual, over six feet tall, very thin and round-shouldered. He was losing his hair and this made his face look even longer, with his gray eyes behind his thin-rimmed glasses." (20)

The Soviet Union

Barr and Sarant told Feklissov they wanted to "build compact computers for military purposes" in the Soviet Union. Their request was granted and they moved to Moscow at the end of 1955. The men were given their own laboratory in Leningrad with the name LKB. Sarant was head engineer and Barr was his deputy. The first LKB computer "turned out ten times smaller than similar Soviet machines, using less electrical power and functioning flawlessly." LKB was the first lab in the Soviet Union to manufacture transistors and integrated circuits. The UM-1 was the first computer to network technological procedures.

Nikita Khrushchev visited LKB to inspect what has been described as a "sort of Silicon Valley before its time". After giving him a radio that was no larger than a pea, Sarant took Khrushchev on a tour of the laboratory. Afterwards he told him: "Nikita Sergeyevich, we are on the threshold of an intellectual revolution that will not only change our way of life but our way of thinking.... You have just seen that in the manufacturing of computers we are practically at the same level as the United States. But we want to pull ahead of America! We need your support. We can make the USSR the first technological power in the world." (21)

A few days after this meeting the Soviet government decided to build a microelectronic center. Three months later the city of Zelonograd was being built thirty miles outside Moscow. The capital was surrounded by satellite cities, each one with a different specialty in nuclear physics, missiles, high tech computers and space travel. Sarant was named director of the centre and Barr became his deputy. However, important figures in the Soviet government disliked the idea of foreigners being in charge of a complex making cutting-edge technology and they were eventually removed from their posts.

Barr continued to be interested in science and patented 250 inventions. "Barr was also an artist... In spite of his age, Barr was still the bohemian he had been when he was younger. His house was always full of artists and musicians while he would be telling jokes, playing the piano, singing and dancing as much as the younger generation." (22) Two of Barr's children fled the Soviet Union and established themselves as musicians in the United States.

In 1974 Alfred Sarant was appointed head of a new laboratory for artificial intelligence in Vladivostok. On 16th March, 1979 he was proposed as a candidate as a member of the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union. He traveled the 5,000 miles to Moscow only to find his jealous colleagues had rejected his candidacy. Sarant was taken ill in the car taking him back to the Moskva Hotel and a few minutes later he died of a heart attack.

In 1990 Barr visited the United States with a delegation of Soviet scientists. Barr decided to live in New York City and in interviews with American newspapers he denied spying for the Soviet Union. He received Soviet Union benefits of $244 per month but found this difficult to live on and had to share an apartment with some old retired friends.

Eventually he decided to return to live in St. Petersburg. In March 1997 he gave a long interview to Komsomolskaya Pravda, where he denied he was ever involved in spying. He also argued that Julius Rosenberg was an innocent victim of McCarthyism and that he planned to organize a Russian-American committee that would campaign for the rehabilitate the Rosenbergs.

Joel Barr died in Moscow on 1st August, 1998.

Primary Sources

(1) Stepan Apresyan, report on Julius Rosenberg (5th December, 1944)

Expedite consent to the joint filming of their materials by both METER (Joel Barr) and HUGHES (Alfred Salent). LIBERAL (Julius Rosenberg) has on hand eight people plus the filming of materials. The state of LIBERAL's health is nothing splendid. We are afraid of putting LIBERAL out of action with overwork.

(2) Steven T. Usdin, Tracking Julius Rosenberg’s Lesser Known Associates (April, 2007)

Barr’s past finally caught up with him more than five years after the FBI first identified him as a security risk and three years after it received definite information that he was a communist party member. In June 1947, a security official at Sperry Gyroscope Company, which hired Barr in October 1946 to work on a classified missile defense project, contacted the FBI to ask about a security clearance for their new employee. The Bureau quickly noted that he had been fired from the army as a subversive and that he was on a list of communist party members. Nonetheless, it spent months collecting documents from the army, interviewing Barr’s neighbors, and peering into his bank accounts. In the first week of October 1947, the Bureau sent a summary of its investigation to Sperry, which fired him a week later.

The FBI’s success in finally ending Barr’s espionage career was marred by its failure to exploit the leads generated by his case. The Bureau treated Barr as a security risk but did not seriously investigate the possibility that he was a Soviet spy. On his job application, which Sperry had turned over to the FBI, Barr had listed three personal references. FBI agents interviewed two of them, but inexplicably ignored the third: Julius Rosenberg. If the agents who reviewed Barr’s file had looked, they would have seen that the Bureau had an extensive file on Rosenberg.

The FBI turned its attention to Barr again in the summer of 1948, when it investigated the possibility that he was the engineer described in Venona decrypts as “Liberal” (the codename was actually assigned to Rosenberg). After learning from Barr’s mother that he was studying electronics in Sweden, the FBI asked the CIA to locate him and monitored the Barr family correspondence. Barr wrote a letter to his mother when he moved to Paris to study music, and the FBI obtained his address from the envelope.

Meanwhile, the Venona decrypts sparked investigations that culminated in the arrests in December 1949 and February 1950, respectively, of atomic spy Klaus Fuchs and his courier, Harry Gold. Gold provided information that led the FBI to David Greenglass, who fingered his brother-in-law, Julius Rosenberg. The spy network unraveled.

(3) Alexander Feklissov, The Man Behind the Rosenbergs (1999)

Barr was out of work by October 1947. He was 32 years old and his chances of securing a job commensurate with his qualifications after such a rejection were basically nil. His love of music took over and since at his age he couldn't hope to become a pianist, he wanted to be a composer. Joel told his new Soviet case officer who was actually only a contact, since he no longer produced any information that he wanted to go to Europe. Even for Soviet intelligence the change in its agent's life was not very attractive, the rule was to help all important sources in their enterprises and to thank them for that they had done in the past. Furthermore, Barr could also become an excellent illegal in the future. Its case officer approved his plan. Out of caution, Joel first went to Belgium, but his destination was Paris. He began by learning to play the piano very well, but he didn't want to go to the Conservatoire because he had his own theory and system. In six months he learned the piano without doing scales, which he hated. He became a pupil of Olivier Messiaen, the famous composer and teacher. The very talented Barr quickly made many friends within international artistic circles. The PGU paid for his studies in Paris just as it had done at Columbia University, in New York.

Naturally, Barr was in contact with an officer at the Paris Rezidentura. After the arrest of Gold and David Greenglass, it became clear that he was running the risk of being arrested as well. An escape route was set up. Czechoslovakia was at that time a hub between Western and Eastern Europe. Easily accessible to Westerners, the country was firmly part of the Socialist bloc. His case officer advised him not to request a visa in France since it was a NATO member and an ally of the United States. Barr went to Switzerland, obtained a visa, and on June 22 arrived by train in Prague. He was now safe.

References

(1) Alexander Feklissov, The Man Behind the Rosenbergs (1999) page 114

(2) Steven T. Usdin, Tracking Julius Rosenberg’s Lesser Known Associates (April, 2007)

(3) Allen Weinstein, The Hunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America (1999) page 217

(4) Alexander Feklissov, The Man Behind the Rosenbergs (1999) pages 116 and 117

(5) Steven T. Usdin, Tracking Julius Rosenberg’s Lesser Known Associates (April, 2007)

(6) Alexander Feklissov, The Man Behind the Rosenbergs (1999) page 117

(7) Alexander Feklissov, The Man Behind the Rosenbergs (1999) page 114

(8) Steven T. Usdin, Tracking Julius Rosenberg’s Lesser Known Associates (April, 2007)

(9) Alexander Feklissov, The Man Behind the Rosenbergs (1999) page 140

(10) Stepan Apresyan, report on Julius Rosenberg (5th December, 1944)

(11) NKVD headquarters, message to Leonid Kvasnikov (23rd February, 1945)

(12) Alexander Feklissov, The Man Behind the Rosenbergs (1999) page 114

(13) Steven T. Usdin, Tracking Julius Rosenberg’s Lesser Known Associates (April, 2007)

(14) Alexander Feklissov, The Man Behind the Rosenbergs (1999) page 253

(15) The New York Tribune (17th June, 1950)

(16) New York Times (17th June, 1950)

(17) New York Daily Mirror (13th July, 1950)

(18) New York Times (18th July, 1950)

(19) Alexander Feklissov, The Man Behind the Rosenbergs (1999) page 253

(20) Alexander Feklissov, The Man Behind the Rosenbergs (1999) page 286

(21) Alfred Salant, quoted in Alexander Feklissov, The Man Behind the Rosenbergs (1999) page 288

(22) Alexander Feklissov, The Man Behind the Rosenbergs (1999) page 291