Nestor Makhno

Nestor Makhno, the son of peasants, was born in Hulyai-Pole, Ukraine, on 27th October 1889. His father died the following year and at the age of seven he was put to work tending cows and sheep for local peasants. Later he found employment as a farm labourer.

In 1906, at the age of seventeen, Makhno joined an anarchist group and became involved in terrorist activities. Two years later he was arrested and sentenced to death but was reprieved because of his youth and imprisoned in Butyrki Prison in Moscow.

Makhno was initially placed in irons or in solitary confinement. Later he shared a cell with an older, more experienced anarchist named Peter Arshinov, who had been imprisoned for smuggling arms from Austria. Over the next few years he taught him about the libertarian doctrine that had been developed by Michael Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin.

Makhno was released from prison after the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II. Makhno later recalled: "The February Revolution of 1917 opened the gates of all Russian prisons for political prisoners. There can be no doubt this was mainly brought about by armed workers and peasants taking to the streets, some in their blue smocks, others in grey military overcoats. These revolutionary workers demanded an immediate amnesty as the first conquest of the Revolution.... The tsarist government of Russia, based on the landowning aristocracy, had walled up these political prisoners in damp dungeons with the aim of depriving the labouring classes of their advanced elements and destroying their means of denouncing the iniquities of the regime. Now these workers and peasants, fighters against the aristocracy, again found themselves free. And I was one of them."

Makhno returned to his native village and assumed a leading role in community affairs. In August 1917 he was elected as chairman of the Hulyai-Pole Soviet of Workers' and Peasants. He now recruited a band of armed men and set about expropriating the estates of the neighboring gentry and distributing the land to the peasants. After the Russian Revolution he became one of the leaders in the area.

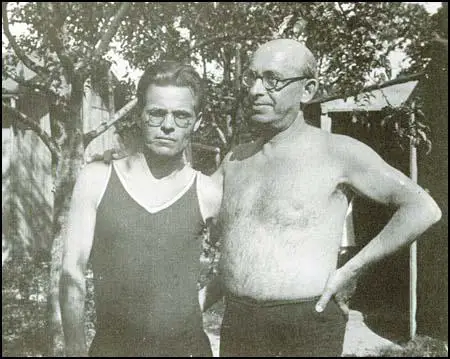

After the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk the German Army marched into the Ukraine. His band of partisans was too weak to offer effective resistance and Makhno was forced to go into hiding. He arrived in Moscow in June 1918. Makhno had a meeting with his hero, Peter Kropotkin, who had arrived in Russia from his long-period in exile.

Makhno also had a meeting with Lenin in the Kremlin. Lenin explained his opposition to anarchists. "The majority of anarchists think and write about the future without understanding the present. That is what divides us Communists from them... But I think that you, comrade, have a realistic attitude towards the burning evils of the time. If only one-third of the anarchist-communists were like you, we Communists would be ready, under certain well-known conditions, to join with them in working towards a free organization of producers." Makhno answered that the anarchists were not utopian dreamers but realistic men of action.

Makhno returned to the Ukraine in July 1918. The area was still occupied by Austrian troops that had installed a puppet ruler, Pavlo Skoropadskyi. Makhno launched a series of raids against the government and the manors of the nobility. As Paul Avrich has pointed out: "Previously independent guerrilla bands accepted Makhno's command and rallied behind his black banner. Villagers provided food and fresh horses, enabling the Makhnovists to travel forty or fifty miles a day with little difficulty. Turning up quite suddenly where least expected, they would attack the gentry and military garrisons, then vanish as quickly as they had come. In captured uniforms they infiltrated the enemy's ranks to learn their plans or to open fire at point-blank range. On one occasion, Makhno and his retinue, masquerading as Hetmanite guardsmen, gained entry to a landowner's ball and fell upon the guests in the midst of their festivities. When cornered, the Makhnovists would bury their weapons, make their way singly back to their villages, and take up work in the fields, awaiting a signal to unearth a new cache of arms and spring up again in an unexpected quarter."

Isaac Babel, a political commissar in the Red Army in the Ukraine wrote: "Makhno was as protean as nature herself. Haycarts deployed in battle array take towns, a wedding procession approaching the headquarters of a district executive committee suddenly opens a concentrated fire, a little priest, waving above him the black flag of anarchy, orders the authorities to serve up the bourgeoisie, the proletariat, wine and music."

Victor Serge argued: "Nestor Makhno, boozing, swashbuckling, disorderly and idealistic, proved himself to be a born strategist of unsurpassed ability. The number of soldiers under his command ran at times into several tens of thousands. His arms he took from the enemy. Sometimes his insurgents marched into battle with one rifle for every two or three men: a rifle which, if any soldier fell, would pass at once from his still-dying hands into those of his alive and waiting neighbour."

Makhno always had a large black flag, the symbol of anarchy, at the head of his army, embroidered with the slogans "Liberty or Death" and "the Land to the Peasants, the Factories to the Workers". Makhno later told Emma Goldman that his objective was to establish a libertarian society in the south that would serve as a model for the whole of Russia. When he set-up his first commune near Pokrovskoye, he named it in honour of Rosa Luxemburg.

In September 1918, after defeating a large force of Austrians at the village of Dibrivki, his men gave him the title, "little father". Two months later the First World War came to an end and all foreign troops left Russia. Pavlo Skoropadskyi was removed from power in an uprising led by Symon Petliura. With the support of the Red Army, Makhno was able to force Petliura into exile.

According to Emma Goldman, she was told by a person living in the Ukraine that "there grew up among the country folk the belief that Makhno was invincible because he had never been wounded during all the years of warfare in spite of his practice of always personally leading every charge."

In 1919, Nestor Makhno married Agafya Kuzmenko, a former elementary schoolteacher (1892-1978), who also served as one of his aides. They had one daughter, Yelena. Two of Makhno's brothers were members of his army before being captured in battle and executed by firing squad.

A pact for joint military action against General Anton Denikin and his White Army was signed in March 1919. However, the Bolsheviks did not trust the anarchists and two months later two Cheka agents sent to assassinate Makhno were caught and executed. Leon Trotsky, commander-in-chief of the Bolsheviks forces, ordered the arrest of Makhno and sent in troops to Hulyai-Pole dissolve the agricultural communes set up by the Makhnovists. With Makhno's power undermined, a few days later, Denikin forces arrived and completed the job, liquidating the local soviets as well.

On 26th September 1919, Makhno launched a successful counterattack at the village of Peregonovka, cutting Denikin's supply lines. This was followed by a new offensive by the Red Army and Denikin's White Army was forced to retreat to the shores of the Black Sea.

Leon Trotsky now turned to dealing with the anarchists and outlawed the Makhnovists. According to the author of Anarchist Portraits (1995): "There ensued eight months of bitter struggle, with losses heavy on both sides. A severe typhus epidemic augmented the toll of victims. Badly outnumbered, Makhno's partisans avoided pitched battles and relied on the guerrilla tactics they had perfected in more than two years of civil war."

A truce was called in October 1920, when General Peter Wrangel and his White Army launched a major offensive in the Ukraine. Trotsky offered to release all anarchists in Russian prison in return for joint military action against Wrangel. However, once the Red Army made sufficient gains to ensure victory in the Civil War, the Makhnovists were once again outlawed. On 25th November, 1920, Makhno's commanders in the Crimea, who had just defeated Wrangel's forces, were seized by the Red Army and executed.

Leon Trotsky now gave orders for an attack on Makhno's headquarters in Hulyai-Pole. Most of his staff were captured and shot but Makhno managed to escape with the remnant of his army. After wandering over the Ukraine for nearly a year, Makhno, suffering from unhealed wounds, crossed the Dniester River into Rumania where he was arrested and interned. He escaped to Poland but was once again arrested and imprisoned in Danzig. Eventually, aided by Alexander Berkman, he was allowed to move to Paris.

Leon Trotsky attempted to explain why he had given orders for Makhno to be assassinated: "Makhno... was a mixture of fanatic and adventurer... Makhno created a cavalry of peasants who supplied their own horses. They were not downtrodden village poor whom the October Revolution first awakened, but the strong and well-fed peasants who were afraid of losing what they had. The anarchist ideas of Makhno (the ignoring of the State, non-recognition of the central power) corresponded to the spirit of the kulak cavalry as nothing else could."

In 1926 Makhno joined forces broke with Peter Arshinov to publish their controversial Organizational Platform, which called for a General Union of Anarchists. This was opposed by Vsevolod Volin, Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, Sébastien Faure and Rudolf Rocker, who argued that the idea of a central committee clashed with the basic anarchist principle of local organisation.

Nestor Makhno was unhappy in Paris saying he hated the "poison" of big cities, and missed the landscape of Hulyai-Pole. According to Alexander Berkman he talked of returning home and "taking up the struggle for liberty and social justice." However, as Paul Avrich points out that he "lived his remaining years in obscurity, poverty, and disease, an Antaeus cut off from the soil that might have replenished his strength."

Nestor Makhno died of tuberculosis on 6th July 1935.

Primary Sources

(1) Victor Serge, Year One of the Revolution (1930)

An Anarchist schoolmaster and former political prisoner, named Nestor Makhno, opened up guerrilla warfare at Gulai-Polye, with fifteen men at his side; these attacked German sentries to obtain weapons. Later on, Makhno was to form whole armies. The Germans repressed these movements with the utmost vigour, executing prisoners en masse and burning down villages; but it was all too much for them.

(2) Peter Wrangel, Memoirs of Genera Wrangel (1929)

After dinner I had two hours with Denikin. In his opinion everything was going splendidly. The possibility of a sudden change in our luck seemed to him to be out of the question. He thought the taking of Moscow was only a question of time, and that the demoralized and weakened enemy could not make a stand against us.

At this point his aide-de-camp brought him a telegram: "It is from General Dragomirov," said Denikin when he had read it. "He says that the General Staff of the Red Army which he had been attacking want to surrender. But General Dragomirov is demanding that this Army should first attack the flank of the other Red Army which is stationed close by."

I drew his attention to the movements of the brigand Makhno and his rebels, for they were threatening our rear.

"Oh, that is not serious! We will finish him off in the twinkling of an eye."

As I listened to him talking, my mind filled with doubt and apprehension.

(3) Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1945) page 142

Nestor Makhno, boozing, swashbuckling, disorderly and idealistic, proved himself to be a born strategist of unsurpassed ability. The number of soldiers under his command ran at times into several tens of thousands. His arms he took from the enemy. Sometimes his insurgents marched into battle with one rifle for every two or three men: a rifle which, if any soldier fell, would pass at once from his still-dying hands into those of his alive and waiting neighbour.

(4) Paul Avrich, Anarchist Portraits (1990)

Makhno received a command to transfer his troops to the Polish front. The order was plainly designed to draw the Insurgent Army away from its home territory, leaving it open to the establishment of Bolshevik rule. Makhno refused to budge. Trotsky, he said, wanted to replace Denikin's forces with the Red Army and the dispossessed landlords with political commissars. Having vowed to cleanse Russia of anarchism "with an iron broom,' a Trotsky replied by again outlawing the Makhnovists. There ensued eight months of bitter struggle, with losses heavy on both sides. A severe typhus epidemic augmented the toll of victims. Badly outnumbered, Makhno's partisans avoided pitched battles and relied on the guerrilla tactics they had perfected in more than two years of civil war.

Hostilities were broken off in October 1920, when Baron Wrangel, Denikin's successor in the south, launched a major offensive, striking northwards from the Crimea. Once more the Red Army enlisted Makhno's aid, in return for which the Communists agreed to an amnesty for all anarchists in Russian prisons and guaranteed the anarchists freedom of propaganda on condition that they refrain from calling for the overthrow of the Soviet government.

Barely a month later, however, the Red Army had made sufficient gains to ensure victory in the Civil War, and the Soviet leaders tore up their agreement with Makhno. Not only had the Makhnovists outlived their usefulness as a military partner, but as long as the bat'ko was at large the spirit of anarchism and the danger of a peasant rising would remain to haunt the Bolshevik regime. On November 25, 1920, Makhno's commanders in the Crimea, fresh from their victory over Wrangel, were seized by the Red Army and shot.

The next day, Trotsky ordered an attack on Makhno's headquarters in Gulyai-Polye, during which Makhno's staff were captured and imprisoned or shot on the spot. The bat'ko himself, however, together with a remnant of an army that had once numbered in the tens of thousands, managed to elude his pursuers. After wandering over the Ukraine for the better part of a year, the guerrilla leader, exhausted and suffering from unhealed wounds, crossed the Dniester River into Rumania and eventually found his way to Paris.

(5) Nestor Makhno, Delo Truda (September 1925)

Anarchism is not merely a doctrine that deals with the social aspect of human life, in the narrow meaning with which the term is invested in political dictionaries and, at meetings, by our propagandist speakers: anarchism is also the study of human life in general.

Over the course of the elaboration of its overall world picture, anarchism has set itself a very specific task: to encompass the world in its entirety, sweeping aside all manner of obstacles, present and yet to come, which might be posed by bourgeois capitalist science and technology, with the aim of providing humanity with the most exhaustive possible explanation of existence in this world and of making the best possible fist of all the problems which may confront it. This approach should help humanity to develop consciousness of the anarchism that is, as far as I know, naturally inherent in us to the extent that humanity is continually being faced with partial manifestations thereof..

Theoretically, anarchism in our day is still regarded as weak, badly developed and even - some would say - often interpreted wrongly in many respects. However, its exponents - they say - have plenty to say about it: many are constantly prattling about it, militating actively and sometimes complaining of its lack of success (I imagine, in this last instance, that this attitude is prompted by the failure to devise, through research, the social wherewithal vital to anarchism if it is to gain a foothold in contemporary society).

In reality, wherever human life is to be found, anarchism is alive. On the other hand, it becomes accessible to the individual only where it boasts propagandists and militants, who have honestly and entirely severed their connections with the slave mentality of our age, something, by the way, that brings savage persecution down upon their heads. Such militants aspire to serve their beliefs unselfishly, without fear of uncovering unsuspected aspects in the course of their development, the better to digest them as they proceed, if need be, and in this way they pave the way for the success of the anarchist spirit over the spirit of submission.

(6) Nestor Makhno, Delo Truda (June 1927)

As far as the question of defence of the revolution generally goes, I shall be relying upon my long experiences first-hand during the Russian revolution in Ukraine, in the course of that unequal, but decisive struggle waged by the revolutionary movement of the Ukrainian working people. Those experiences taught me, firstly, that the defence of the revolution is directly bound up with the revolution's offensive against the counter-revolution. Secondly, the growth and development of the forces for the defence of the revolution are at all times conditioned by the resistance of the counter-revolutionaries. And thirdly, what follows from the above, namely that revolutionary actions in the majority of cases are closely dependent on the political content, structure and organizational methods adopted by the armed revolutionary detachments, who are obliged to confront conventional, counter-revolutionary armies along a huge front.

In its fight against the counter-revolution, the Russian revolution at first began by organizing Red Guard detachments under the leadership of the bolsheviks. It was very quickly spotted the Red Guards failed to withstand the pressures from the organized counter-revolution, to be specific, the German, Austrian and Hungarian expeditionary corps, for the simple reason that, most of the time, they operated without any overall operational guide-lines. That is why the bolsheviks turned to the organization of a Red Army in the spring of 1918.

It was then that we issued the call to form "free battalions" of Ukrainian working people. It quickly transpired that the organization of the "free battalions" in the spring of 1918 was powerless to survive internal provocations of every sort, given that, without adequate vetting, political or social, it took in all volunteers provided only that they wanted to take up their weapons and fight. That was why the armed units established by that organization were treacherously delivered to the counter-revolutionaries. And this prevented it from seeing through its historical mission in the fight against the German, Austrian and Hungarian counter-revolution.

(7) In March, 1937, Leon Trotsky, wrote an article, Amoralism and Kronstadt , where he replied to charges made by Wendelin Thomas, that Bolshevism and Stalinism were closely linked. Thomas used the example of how Trotsky and Vladimir Lenin, dealt with opponents such as the Mensheviks, the Socialist Revolutionaries and the Kronstadt Rebellion.

Your evaluation of the Kronstadt Uprising of 1921 is basically incorrect. The best, most sacrificing sailors were completely withdrawn from Kronstadt and played an important role at the fronts and in the local Soviets throughout the country. What remained was the grey mass with big pretensions, but without political education and unprepared for revolutionary sacrifice. The country was starving. The Kronstadters demanded privileges. The uprising was dictated by a desire to get privileged food rations.

No less erroneous is your estimate of Makhno. In himself he was a mixture of fanatic and adventurer. He became the concentration of the very tendencies which brought about the Kronstadt Uprising. Makhno created a cavalry of peasants who supplied their own horses. They were not downtrodden village poor whom the October Revolution first awakened, but the strong and well-fed peasants who were afraid of losing what they had.

The anarchist ideas of Makhno (the ignoring of the State, non-recognition of the central power) corresponded to the spirit of the kulak cavalry as nothing else could. I should add that the hatred of the city and the city worker on the part of the followers of Makhno was complemented by the militant anti-Semitism.