Sacco-Vanzetti Case

On 15th April, 1920, Frederick Parmenter and Alessandro Berardelli, in South Braintree, were shot dead while carrying two boxes containing the payroll of a shoe factory. After the two robbers took the $15,000 they got into a car containing several other men and were driven away.

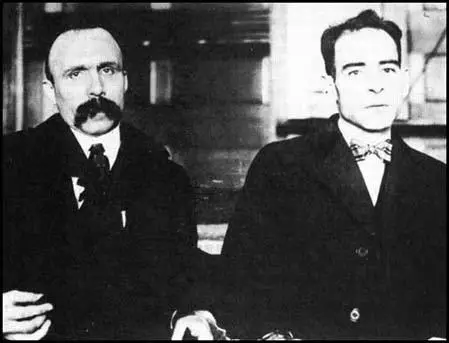

Several eyewitnesses claimed that the robbers looked Italian. A large number of Italian immigrants were questioned but eventually the authorities decided to charge Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco with the murders. Although the two men did not have criminal records, it was argued that they had committed the robbery to acquire funds for their anarchist political campaign.

Fred H. Moore, a socialist lawyer, agreed to defend the two men. Eugene Lyons, a young journalist, carried out research for Moore. Lyons later recalled: "Fred Moore, by the time I left for Italy, was in full command of an obscure case in Boston involving a fishmonger named Bartolomeo Vanzetti and a shoemaker named Nicola Sacco. He had given me explicit instructions to arouse all of Italy to the significance of the Massachusetts murder case, and to hunt up certain witnesses and evidence. The Italian labor movement, however, had other things to worry about. An ex-socialist named Benito Mussolini and a locust plague of blackshirts, for instance. Somehow I did get pieces about Sacco and Vanzetti into Avanti!, which Mussolini had once edited, and into one or two other papers. I even managed to stir up a few socialist onorevoles, like Deputy Mucci from Sacco's native village in Puglia, and Deputy Misiano, a Sicilian firebrand at the extreme Left. Mucci brought the Sacco-Vanzetti affair to the floor of the Chamber of Deputies, the first jet of foreign protest in what was eventually to become a pounding international flood."

The trial started on 21st May, 1921. The main evidence against the men was that they were both carrying a gun when arrested. Some people who saw the crime taking place identified Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco as the robbers. Others disagreed and both men had good alibis. Vanzetti was selling fish in Plymouth while Sacco was in Boston with his wife having his photograph taken. The prosecution made a great deal of the fact that all those called to provide evidence to support these alibis were also Italian immigrants.

Vanzetti and Sacco were disadvantaged by not having a full grasp of the English language. Webster Thayer, the judge was clearly prejudiced against anarchists. The previous year, he rebuked a jury for acquitting anarchist Sergie Zuboff of violating the criminal anarchy statute. It was clear from some of the answers Vanzetti and Sacco gave in court that they had misunderstood the question. During the trial the prosecution emphasized the men's radical political beliefs. Vanzetti and Sacco were also accused of unpatriotic behaviour by fleeing to Mexico during the First World War.

Eugene Lyons has argued in his autobiography, Assignment in Utopia (1937): "Fred Moore was at heart an artist. Instinctively he recognized the materials of a world issue in what appeared to others a routine matter... When the case grew into a historical tussle, these men were utterly bewildered. But Moore saw its magnitude from the first. His legal tactics have been the subject of dispute and recrimination. I think that there is some color of truth, indeed, to the charge that he sometimes subordinated the literal needs of legalistic procedure to the larger needs of the case as a symbol of class struggle. If he had not done so, Sacco and Vanzetti would have died six years earlier, without the solace of martyrdom. With the deliberation of a composer evolving the details of a symphony which he senses in its rounded entirety, Moore proceeded to clarify and deepen the elements implicit in the case. And first of all he aimed to delineate the class character of the automatic prejudices that were operating against Sacco and Vanzetti. Sometimes over the protests of the men themselves he cut through legalistic conventions to reveal underlying motives. Small wonder that the pinched, dyspeptic judge and the pettifogging lawyers came to hate Moore with a hatred that was admiration turned inside out."

In court Nicola Sacco claimed: "I know the sentence will be between two classes, the oppressed class and the rich class, and there will be always collision between one and the other. We fraternize the people with the books, with the literature. You persecute the people, tyrannize them and kill them. We try the education of people always. You try to put a path between us and some other nationality that hates each other. That is why I am here today on this bench, for having been of the oppressed class. Well, you are the oppressor." The trial lasted seven weeks and on 14th July, 1921, both men were found guilty of first degree murder and sentenced to death. The journalist. Heywood Broun, reported that when Judge Thayer passed sentence upon Sacco and Vanzetti, a woman in the courtroom said with terror: "It is death condemning life!"

Bartolomeo Vanzetti commented in court after the sentence was announced: "The jury were hating us because we were against the war, and the jury don't know that it makes any difference between a man that is against the war because he believes that the war is unjust, because he hate no country, because he is a cosmopolitan, and a man that is against the war because he is in favor of the other country that fights against the country in which he is, and therefore a spy, an enemy, and he commits any crime in the country in which he is in behalf of the other country in order to serve the other country. We are not men of that kind. Nobody can say that we are German spies or spies of any kind... I never committed a crime in my life - I have never stolen and I have never killed and I have never spilt blood, and I have fought against crime, and I have fought and I have sacrificed myself even to eliminate the crimes that the law and the church legitimate and sanctify."

Many observers believed that their conviction resulted from prejudice against them as Italian immigrants and because they held radical political beliefs. The case resulted in anti-US demonstrations in several European countries and at one of these in Paris, a bomb exploded killing twenty people.

In 1925 Celestino Madeiros, a Portuguese immigrant, confessed to being a member of the gang that killed Frederick Parmenter and Alessandro Berardelli. He also named the four other men, Joe, Fred, Pasquale and Mike Morelli, who had taken part in the robbery. The Morelli brothers were well-known criminals who had carried out similar robberies in area of Massachusetts. However, the authorities refused to investigate the confession made by Madeiros.

Important figures in the United States and Europe became involved in the campaign to overturn the conviction. John Dos Passos, Alice Hamilton, Paul Kellog, Jane Addams, Heywood Broun, William Patterson, Upton Sinclair, Dorothy Parker, Ruth Hale, Ben Shahn, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Felix Frankfurter, Susan Gaspell, Mary Heaton Vorse, Gardner Jackson, John Howard Lawson, Freda Kirchway, Floyd Dell, Katherine Anne Porter, Michael Gold, Bertrand Russell, John Galsworthy, Arnold Bennett, George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells became involved in a campaign to obtain a retrial. Although Webster Thayer, the original judge, was officially criticised for his conduct at the trial, the authorities refused to overrule the decision to execute the men. One of the campaigners, Anatole France, commented: "The death of Sacco and Vanzetti will make martyrs of them and cover you with shame. Save them for your honor, for the honor of your children, and for the generations yet unborn."

Eugene Debs, the leader of the Socialist Party of America, called for trade union action against the decision: "The supreme court of Massachusetts has spoken at last and Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco, two of the bravest and best scouts that ever served the labor movement, must go to the electric chair.... Now is the time for all labor to be aroused and to rally as one vast host to vindicate its assailed honor, to assert its self-respect, and to issue its demand that in spite of the capitalist-controlled courts of Massachusetts honest and innocent working-men whose only crime is their innocence of crime and their loyalty to labor, shall not be murdered by the official hirelings of the corporate powers that rule and tyrannize over the state."

In 1927 Governor Alvan T. Fuller appointed a three-member panel of Harvard President Abbott Lawrence Lowell, the President of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Samuel W. Stratton, and the novelist, Robert Grant to conduct a complete review of the case and determine if the trials were fair. The committee reported that no new trial was called for and based on that assessment Governor Fuller refused to delay their executions or grant clemency. Walter Lippmann, who had been one of the main campaigners for Sacco and Vanzetti, argued that Governor Fuller had "sought with every conscious effort to learn the truth" and that it was time to let the matter drop.

Heywood Broun disagreed and on 5th August he wrote in New York World: "Alvan T. Fuller never had any intention in all his investigation but to put a new and higher polish upon the proceedings. The justice of the business was not his concern. He hoped to make it respectable. He called old men from high places to stand behind his chair so that he might seem to speak with all the authority of a high priest or a Pilate. What more can these immigrants from Italy expect? It is not every prisoner who has a President of Harvard University throw on the switch for him. And Robert Grant is not only a former Judge but one of the most popular dinner guests in Boston. If this is a lynching, at least the fish peddler and his friend the factory hand may take unction to their souls that they will die at the hands of men in dinner coats or academic gowns, according to the conventionalities required by the hour of execution."

The following day Broun returned to the attack. He argued that Governor Alvan T. Fuller had vindicated Judge Webster Thayer "of prejudice wholly upon the testimony of the record". Broun had pointed out that Fuller had "overlooked entirely the large amount of testimony from reliable witnesses that the Judge spoke bitterly of the prisoners while the trial was on." Broun added: "It is just as important to consider Thayer's mood during the proceedings as to look over the words which he uttered. Since the denial of the last appeal, Thayer has been most reticent, and has declared that it is his practice never to make public statements concerning any judicial matters which come before him. Possibly he never did make public statements, but certainly there is a mass of testimony from unimpeachable persons that he was not so careful in locker rooms and trains and club lounges."

It now became clear that Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti would be executed. Vanzetti commented to a journalist: "If it had not been for this thing, I might have lived out my life talking at street corners to scorning men. I might have died, unmarked, unknown, a failure. Now we are not a failure. This is our career and our triumph. Never in our full life can we hope to do such work for tolerance, justice, for man's understanding of man, as now we do by accident. Our words - our lives - our pains - nothing! The taking of our lives - lives of a good shoemaker and a poor fish peddler - all! That last moment belong to us - that agony is our triumph. On 23rd August 1927, the day of execution, over 250,000 people took part in a silent demonstration in Boston.

Soon after the executions Eugene Lyons published his book, The Life and Death of Sacco and Vanzetti (1927): "It was not a frame-up in the ordinary sense of the word. It was a far more terrible conspiracy: the almost automatic clicking of the machinery of government spelling out death for two men with the utmost serenity. No more laws were stretched or violated than in most other criminal cases. No more stool-pigeons were used. No more prosecution tricks were played. Only in this case every trick worked with a deadly precision. The rigid mechanism of legal procedure was at its most unbending. The human beings who operated the mechanism were guided by dim, vague, deep-seated motives of fear and self-interest. It was a frame-up implicit in the social structure. It was a perfect example of the functioning of class justice, in which every judge, juror, police officer, editor, governor and college president played his appointed role easily and without undue violence to his conscience. A few even played it with an exalted sense of their own patriotism and nobility."

The United States system of justice came under attack from important figures throughout the world. Bertrand Russell argued: "I am forced to conclude that they were condemned on account of their political opinions and that men who ought to have known better allowed themselves to express misleading views as to the evidence because they held that men with such opinions have no right to live. A view of this sort is one which is very dangerous, since it transfers from the theological to the political sphere a form of persecution which it was thought that civilized countries had outgrown."

The novelist, Upton Sinclair, decided to investigate the case. He interviewed Fred H. Moore, one of defence lawyers in the case. According to Sinclair's latest biographer, Anthony Arthur: "Fred Moore, Sinclair said later, who confirmed his own growing doubts about Sacco's and Vanzetti's innocence. Meeting in a hotel room in Denver on his way home from Boston, he and Moore talked about the case. Moore said neither man ever admitted it to him, but he was certain of Sacco's guilt and fairly sure of Vanzetti's knowledge of the crime if not his complicity in it." A letter written by Sinclair at the time acknowledged that he had doubts about Moore's testimony: "I realized certain facts about Fred Moore. I had heard that he was using drugs. I knew that he had parted from the defense committee after the bitterest of quarrels.... Moore admitted to me that the men themselves had never admitted their guilt to him, and I began to wonder whether his present attitude and conclusions might not be the result of his brooding on his wrongs."

Sinclair was now uncertain if a miscarriage of justice had taken place. He decided to end the novel on a note of ambiguity concerning the guilt or innocence of the Italian anarchists. When Robert Minor, a leading figure in the American Communist Party, discovered Sinclair's intentions he telephoned him and said: "You will ruin the movement! It will be treason!" Sinclair's novel, Boston, appeared in 1928. Unlike some of his earlier radical work, the novel received very good reviews. The New York Times called it a "literary achievement" and that it was "full of sharp observation and savage characterization," demonstrating a new "craftsmanship in the technique of the novel".

Fifty years later, on 23rd August, 1977, Michael Dukakis, the Governor of Massachusetts, issued a proclamation, effectively absolving the two men of the crime. "Today is the Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti Memorial Day. The atmosphere of their trial and appeals were permeated by prejudice against foreigners and hostility toward unorthodox political views. The conduct of many of the officials involved in the case shed serious doubt on their willingness and ability to conduct the prosecution and trial fairly and impartially. Simple decency and compassion, as well as respect for truth and an enduring commitment to our nation's highest ideals, require that the fate of Sacco and Vanzetti be pondered by all who cherish tolerance, justice and human understanding."

Primary Sources

(1) Frederick Lewis Allen, Only Yesterday (1931)

At the height of the Big Red Scare - in April, 1920 - there had taken place at South Braintree, Massachusetts, a crime so unimportant that it was not even mentioned in the New York Times of the following day - or, for that matter, of the whole following year. It was the sort of crime which was taking place constantly all over the country. A paymaster and his guard, carrying two boxes containing the pay-roll of a shoe factory, were killed by two men with pistols, who thereupon leaped into an automobile which drew up at the kerb, and drove away across the railroad tracks. Two weeks later a couple of Italian radicals were arrested as the murders, and a year later the Italians were tried before Judge Webster Thayer and a jury and found guilty.

(2) Eugene Debs, statement issued in October, 1926.

The supreme court of Massachusetts has spoken at last and Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco, two of the bravest and best scouts that ever served the labor movement, must go to the electric chair. The decision of this capitalist judicial tribunal is not surprising. It accords perfectly with the tragical farce and the farcical tragedy of the entire trial of these two absolutely innocent and shamefully persecuted working men.

Now is the time for all labor to be aroused and to rally as one vast host to vindicate its assailed honor, to assert its self-respect, and to issue its demand that in spite of the capitalist-controlled courts of Massachusetts honest and innocent working-men whose only crime is their innocence of crime and their loyalty to labor, shall not be murdered by the official hirelings of the corporate powers that rule and tyrannize over the state.

(3) John Dos Passos, Facing the Chair: Sacco and Vanzetti (1927)

Why were these men held as murderers and highwaymen and not as anarchists and advocates of the working people? Among a people that does not recognize or rather does not admit the force and danger of ideas it is impossible to prosecute the holder of unpopular ideas directly. Also there is a smoldering tradition of freedom that makes those who do it feel guilty. After all everyone learnt the Declaration of Independence and "Give me Liberty or Give me Death" in school, and however perfunctory the words have become they have left a faint infantile impression on the minds of most of us. Hence the characteristic American weapon of the frameup. If two Italians are spreading anarchist propaganda, you hold them for murder.

(4) Bertrand Russell led the campaign in Britain against the conviction of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti.

I am forced to conclude that they were condemned on account of their political opinions and that men who ought to have known better allowed themselves to express misleading views as to the evidence because they held that men with such opinions have no right to live. A view of this sort is one which is very dangerous, since it transfers from the theological to the political sphere a form of persecution which it was thought that civilized countries had outgrown.

(5) William Patterson, The Man Who Cried Genocide (1971)

Sacco and Vanzetti became friends during World War I. Rather than go to war to kill their fellow-workers, they had joined a group of anarchists who went to live in Mexico for the duration of the war. Their friendship continued when they returned to Massachusetts.

In the police files there was quite a dossier under the designation "agitators" concerning these two men. Vanzetti had led a strike at a cordage factory for which he was blacklisted. Sacco had raised money to fight frame-ups, he had walked picket lines, had been arrested for demonstrating. Both were very active in the defense of the foreign-born, who were at that time the targets of a sweeping witch hunt, under the guidance of U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer and J. Edgar Hoover. The two friends had organized protest meetings, raised defense money, distributed handbills. They were often followed by spies hired by the federal government.

A protest meeting that Sacco and Vanzetti were organizing for May 9, 1920 never came off. On May 5 they were arrested, charged with dangerous radical activities. But even the authorities must have felt this an insufficient charge, for they added another - they associated them with a payroll robbery at South Braintree, Mass., on April 15, 1920, in which two guards had been killed.

At their trial. Judge Webster Thayer, who presided, revealed at every turn his marked hatred for the two Italians. Every effort was made by the press and the authorities to whip up mass mob hysteria. The courtroom was surrounded with extra guards, and everyone entering it was searched. Suborned witnesses calmly lied on the stand, with the knowledge, undoubtedly, that even if they were charged with having given perjured testimony they would go free.

(6) Bartolomeo Vanzetti, statement (9th April, 1927)

I have suffered for things that I am guilty of. I am suffering because I am a radical and indeed I am a radical; I have suffered because I was an Italian, and indeed I am an Italian; I have suffered more for my family and for my beloved than for myself; but I am so convinced to be right that if you could execute me two times, and if I could be reborn two other times, I would live again to do what I have done already.

(7) Bartolomeo Vanzetti, comment to a reporter before his execution (1927)

If it had not been for this thing, I might have lived out my life talking at street corners to scorning men. I might have died, unmarked, unknown, a failure. Now we are not a failure. This is our career and our triumph. Never in our full life can we hope to do such work for tolerance, justice, for man's understanding of man, as now we do by accident. Our words - our lives - our pains - nothing! The taking of our lives - lives of a good shoemaker and a poor fish peddler - all! That last moment belong to us - that agony is our triumph.

(8) Freda Kirchway was in Germany during the last few weeks before Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco were executed. She wrote about her reaction to the execution in The Nation (28th August, 1927)

We've hardly talked about it - but every time we got within range of a newspaper we've rushed to it hoping, without any real hope that some miracle of mercy would have descended on the Governor or someone else. It was hard to sleep through some of those nights. And everywhere we went - from Paris and Berlin to Heiligenblut in the Austrian Tyrol - people talked to us about it with horror and a complete inability to understand. This was true of people without any political feeling in the matter - casual companions in a railway compartment or in a hotel office. And now they're dead. In spite of riots and bitter resentment, I feel, in people and in myself a distinct relief that, if it had to be, it is done. Anything is better than that strain of waiting.

(9) Edna St. Vincent Millay, Justice Denied in Massachusetts (1927)

Let us abandon then our gardens and go home

And sit in the sitting-room.

Shall the larkspur blossom or the corn grow under the cloud?

Sour to the fruitful seed

Is the cold earth under this cloud,

Fostering quack and weed, we have marched upon but cannot conquer;

We have bent the blades of our hoes against the stalks of them.

Let us go home, and sit in the sitting-room.

Not in our day

Shall the cloud go over and the sun rise as before,

Beneficent upon us

Out of the glittering bay,

And the warm winds be blown inward from the sea

Moving the blades of corn

With a peaceful sound.

Forlorn, forlorn,

Stands the blue hay-rack by the empty mow.

And the petals drop to the ground,

Leaving the tree unfruited.

The sun that warmed our stooping backs and withered the weed uprooted -

We shall not feel it again.

We shall die in darkness, and be buried in the rain.

What from the splendid dead

We have inherited -

Furrows sweet to the grain, and the weed subdued -

See now the slug and the mildew plunder.

Evil does not overwhelm

The larkspur and the corn;

We have seen them go under.

Let us sit here, sit still,

Here in the sitting-room until we die;

At the step of Death on the walk, rise and go;

Leaving to our children's children this beautiful doorway,

And this elm,

And a blighted earth to till

With a broken hoe.

(10) Eugene Lyons, The Life and Death of Sacco and Vanzetti (1927)

These aliens by a strange chance combined in their obscure persons all the things that most offended and frightened a smug New Englander. In a section where family pride and an ingrown sense of racial superiority flourished, Sacco and Vanzetti were from the lowest social layer of wops and hunkies and polaks. At a time when Bolshevism gave householders nightmares, Sacco and Vanzetti were by their own confession reddest of the Reds. With the textile industry drifting to the South and the shoe industry to the West, in a period of strikes and discontent, Sacco and Vanzetti were self-confessed labor agitators. Amidst a raging blood-fed patriotism, they were slackers. In Puritan New England they were atheists.

It required no special effort or apparatus to generate fear of and hatred for the two men. They attracted the fears and hatreds already in full play. The belief of some that agents of the Department of Justice and of the State of Massachusetts got together and decided to electrocute them, innocent or guilty, is naive.

It was not a frame-up in the ordinary sense of the word. It was a far more terrible conspiracy: the almost automatic clicking of the machinery of government spelling out death for two men with the utmost serenity. No more laws were stretched or violated than in most other criminal cases. No more stool-pigeons were used. No more prosecution tricks were played. Only in this case every trick worked with a deadly precision. The rigid mechanism of legal procedure was at its most unbending. The human beings who operated the mechanism were guided by dim, vague, deep-seated motives of fear and self-interest.

It was a frame-up implicit in the social structure. It was a perfect example of the functioning of class justice, in which every judge, juror, police officer, editor, governor and college president played his appointed role easily and without undue violence to his conscience. A few even played it with an exalted sense of their own patriotism and nobility.

(11) H. G. Wells became involved in the campaign in Britain against the conviction of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti in America. The New York Times refused to publish his article, The Proposed Murder of Two Radicals. It eventually appeared in his book of essays, The Way the World is Going, in 1929.

The elementary education of the American citizen is cheap and poor and does not fit him for his proper role in the world; next, that the methods of democracy used by the States are crude and ineffective and that they hamper the moral and intellectual development of what is still the greatest, most promising of human communities; and, thirdly and finally, that the American sense of justice is clumsy and confused.

(12) Eugene Lyons, Assignment in Utopia (1937)

Sacco was the Latin at his most impetuous, a man of emotion rather than logic, driven literally to madness on at least two occasions by the ordeal of imprisonment and waiting. The separation from his pretty red-headed wife and his two children, from friends and work, consumed his flesh and shook his reason. A week of incarceration for a man like Sacco was more terrible than a year for the more phlegmatic and contemplative Vanzetti. Sacco was a caged and raging animal; Vanzetti seemed a monk in calm seclusion. Under the ferocious Italian mustaches which gave him a look of fierceness in the eyes of the ordinary American, the fishmonger from Piemonte had ascetic features and eyes of a tenderness that haunted one.

With every year of imprisonment Vanzetti seemed to grow calmer, gentler, more philosophic. His was the consolation of genuine martyrdom in which there was no rancor but an ever-deepening understanding. Where, Saco had acquired his anarchist beliefs at second-hand, more attracted by its harsh code than its philosophy, Vanzetti had read and studied the poets and prophets of his faith. His mind was crystal clear and expanded immensely in the enforced leisure of his seven years' isolation. Some of his letters and speeches from the prisoners' cage have the ring of enduring literature-this despite his use of English, an alien, half-apprehended tongue. Certainly the scene while he was being strapped into the electric chair, when he proffered his forgiveness to those who were about to snuff out his life, belongs among the high moments in the history of the human spirit.

(13) Heywood Broun, New York World (5th August, 1927)

When at last Judge Thayer in a tiny voice passed sentence upon Sacco and Vanzetti, a woman in the courtroom said with terror: "It is death condemning life!"

The men in Charlestown Prison are shining spirits, and Vanzetti has spoken with an eloquence not known elsewhere within our time. They are too bright, we shield our eyes and kill them. We are the dead, and in us there is not feeling nor imagination nor the terrible torment of lust for justice. And in the city where we sleep smug gardeners walk to keep the grass above our little houses sleek and cut whatever blade thrusts up a head above its fellows.

"The decision is unbelievably brutal," said the Chairman of the Defense Committee, and he was wrong. The thing is worthy to be believed. It has happened. It will happen again, and the shame is wider than that which must rest upon Massachusetts. I have never believed that the trial of Sacco and Vanzetti was one set apart from many by reason of the passion and prejudice which encrusted all the benches. Scratch through the varnish of any judgment seat and what will you strike but hate thick-clotted from centuries of angry verdicts? Did any man ever find power within his hand except to use it as a whip?

Gov. Alvan T. Fuller never had any intention in all his investigation but to put a new and higher polish upon the proceedings. The justice of the business was not his concern. He hoped to make it respectable. He called old men from high places to stand behind his chair so that he might seem to speak with all the authority of a high priest or a Pilate.

What more can these immigrants from Italy expect? It is not every prisoner who has a President of Harvard University throw on the switch for him. And Robert Grant is not only a former Judge but one of the most popular dinner guests in Boston. If this is a lynching, at least the fish peddler and his friend the factory hand may take unction to their souls that they will die at the hands of men in dinner coats or academic gowns, according to the conventionalities required by the hour of execution.

Already too much has been made of the personality of Webster Thayer. To sympathizers of Sacco and Vanzetti he has seemed a man with a cloven hoof. But in no usual sense of the term is this man a villain. Although probably not a great jurist, he is without doubt as capable and conscientious as the average Massachusetts Judge, and if that's enough to warm him in wet weather by all means let him stick the compliment against his ribs.

Webster Thayer has a thousand friends. He has courage, sincerity and convictions. Judge Thayer is a good man, and when he says that he made every effort to give a fair trial to the Anarchists brought before him, undoubtedly he thinks it and he means it. Quite often I've heard the remark: "I wonder how that man sleeps at night?" On this point I have no first hand information, but I venture to guess that he is no more beset with uneasy dreams than most of us. He saw his duty and he thinks he did it.

And Gov. Fuller, also, is not in any accepted sense of the word a miscreant. Before becoming Governor he manufactured bicycles. Nobody was cheated by his company. He loves his family and pays his debts. Very much he desires to be Governor again, and there is an excellent chance that this ambition will be gratified. Other Governors of Massachusetts have gone far, and it is not fantastic to assume that some day he might be President. His is not a master mind, but he is a solid and substantial American, chiming in heartily with all our national ideals and aspirations.

To me the tragedy of the conviction of Sacco and Vanzetti lies in the fact that this was not a deed done by crooks and knaves. In that case we could have a campaign with the slogan "Turn the rascals out," and set up for a year or two a reform Administration. Nor have I had much patience with any who would like to punish Thayer by impeachment or any other process. Unfrock him and his judicial robes would fall upon a pair of shoulders not different by the thickness of a fingernail. Men like Holmes and Brandeis do not grow on bushes. Popular government, as far as the eye can see, is always going to be administered by the Thayers and Fullers.

It has been said that the question at issue was not the guilt or innocence of Sacco and Vanzetti, but whether or not they received a fair trial. I will admit that this commands my interest to some extent, but still I think it is a minor phase in the whole matter. From a Utopian point of view the trial was far from fair, but it was not more biased than a thousand which take place in this country every year. It has been pointed out that the Public Prosecutor neglected to call certain witnesses because their testimony would not have been favorable to his case. Are there five District Attorneys, is there one, in the whole country who would do otherwise?

(14) Heywood Broun, New York World (6th August, 1927)

Several points in the official decision of Gov. Fuller betray a state of mind unfortunate under the circumstances. It seems to me that the whole tone of Gov. Fuller's statement was apologetic, but this perhaps is debatable. There can be no question, however, that he fell into irrelevancies.

"The South Braintree crime was particularly brutal," he wrote, and went on to describe the manner in which the robbers pumped bullets into a guard who was already wounded and helpless. Surely this is beside the point. Had this been one of the most considerate murders ever committed in the State of Massachusetts, Sacco and Vanzetti would still have been deserving of punishment if guilty. The contention of the defense has always been that the accused men had no part in the affair. The savagery of the killing certainly is wholly extraneous to the issue.

But these references of the Governor are worse than mere wasted motion. Unconsciously he has made an appeal to that type of thinker who says: "Why all this sympathy for those two anarchists and none for the unfortunate widow of the paymaster's guard?" But those of us who are convinced that Sacco and Vanzetti are innocent certainly pay no disrespect to the woes of the widow.

Again Gov. Fuller writes: "It is popularly supposed that he (Madeiros) confessed to committing the crime." Surely this gives the impression that no such statement ever came from the condemned criminal. The Governor may be within his rights in deciding that Madeiros lied, and for some self-seeking reason, but it is not only popularly supposed but also true that he did make a confession.

"In his testimony to me," the Governor explains, "he could not recall the details or describe the neighborhood."

This, I must say, seems to me a rather frowsy sort of psychology. Assuming that Madeiros took part in the crime, fired some shots and sped quickly away in an automobile, how could he be expected to remember the happenings in any precise detail? I have known men who ran seventy yards across the goal line in some football game and after this was over they knew little or nothing of what happened while excitement gripped them. I would be much more inclined to believe Madeiros a liar if he had been able to give a detailed and graphic account of everything which happened during the flurry.

And again, the Massachusetts Executive is far too cavalier in dealing with Sacco's alibi.

"He then claimed," says the Governor, "to have been at the Italian Consulate in Boston on that date, but the only confirmation of this claim is the memory of a former employee of the Consulate who made a deposition in Italy that Sacco among forty others was in the office that day. This employee had no memorandum to assist his memory."

In this brief paragraph I think I detect much bias. By speaking of the witness as "a former employee," Gov. Fuller seems to endeavor to discredit him. And yet the man who testified may be wholly worthy to be believed, even though he eventually took another job. Nor does the fact that his deposition was made in Italy militate against it. Truth may travel even across an ocean.

Assuming that Sacco did go to the Consulate as he has said, why should it be expected that his arrival would create such a stir that everyone there from the Consul down would have marked his coming indelibly? And this witness for the defense, according to Fuller, "had no memorandum to assist his memory." Why in Heaven's name should it be assumed that he would? There were other witnesses to whom the Governor gave credence who did not come with blueprints or flashlight photographs of happenings. Memory was all that served them and yet Fuller believed because he chose to.

One important point the Governor neglected to mention in dealing with the testimony of the Consulate clerk. The employee happened to fix Sacco in his mind by reason of a striking circumstance. The laborer, ignorant of passport requirements, brought with him to the Consulate not the conventional miniature but a large-sized crayon enlargement. And to my mind this should have been a clinching factor in the validity of the alibi.

Gov. Fuller has vindicated Judge Thayer of prejudice wholly upon the testimony of the record. Apparently he has overlooked entirely the large amount of testimony from reliable witnesses that the Judge spoke bitterly of the prisoners while the trial was on. The record is not enough. Anybody who has ever been to the theater knows it is impossible to evaluate the effect of a line until you hear it read. It is just as important to consider Thayer's mood during the proceedings as to look over the words which he uttered.

Since the denial of the last appeal, Thayer has been most reticent, and has declared that it is his practice never to make public statements concerning any judicial matters which come before him. Possibly he never did make public statements, but certainly there is a mass of testimony from unimpeachable persons that he was not so careful in locker rooms and trains and club lounges.

Nor am I much moved at the outcries of admiration from editorial writers who have expressed delight at the courage of the Governor of Massachusetts. Readily I will admit that by his decision he has exposed himself to the danger of physical violence. This is courage, but it is one of the more usual varieties. To decide in favor of Sacco and Vanzetti would have required a very different sort of courage. Such action upon Fuller's part might very possibly have blasted his political future.

I am afraid there is no question that a vast majority of the voters in the Bay State want to see the condemned men die. I don't know why. Clearly it depends upon no careful examination of the evidence. Mostly the feeling rests upon the fact that Sacco and Vanzetti are radicals and that they are foreigners. Also the backbone of Massachusetts, such as it is, happens to be up because of criticism beyond the borders of the State. "This is only our business," say the citizens of the Commonwealth, and they are very wrong.

Five times as many telegrams of praise as those of censure have come to the Governor, according to the official statement of his secretary. In such circumstances it seems to me that his courage in the business is of no great importance.

From now on, I want to know, will the institution of learning in Cambridge which once we called Harvard be known as Hangman's House?

(15) Michael Dukakis, Governor of Massachusetts, proclamation on the Sacco and Vanzetti case (23rd August, 1977)

Today is the Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti Memorial Day. The atmosphere of their trial and appeals were permeated by prejudice against foreigners and hostility toward unorthodox political views. The conduct of many of the officials involved in the case shed serious doubt on their willingness and ability to conduct the prosecution and trial fairly and impartially. Simple decency and compassion, as well as respect for truth and an enduring commitment to our nation's highest ideals, require that the fate of Sacco and Vanzetti be pondered by all who cherish tolerance, justice and human understanding.

(16) Paul Avrich, Anarchist Portraits (1990)

The trial, occurring in the wake of the Red Scare, took place in an atmosphere of intense hostility towards the defendants. The district attorney, Frederick G. Katzmann, conducted a highly unscrupulous prosecution, coaching and badgering witnesses, withholding exculpatory evidence from the defense, and perhaps even tampering with physical evidence. A skillful and ruthless cross-examiner, he played on the emotions of the jurors, arousing their deepest prejudices against the accused. Sacco and Vanzetti were armed; they were foreigners, atheists, anarchists. This overclouded all judgment. The judge in the case, Webster Thayer, likewise revealed his bias. Outside the courtroom, during the trial and the appeals that followed, he made remarks that bristled with animosity towards the defendants ("Did you see what I did with those anarchistic bastards the other day? I guess that will hold them for a while.")' When a verdict of guilty was returned, many believed that the men had been convicted because of their foreign birth and radical beliefs, not on solid evidence of criminal guilt.

In the aftermath of the trial, as legal appeals delayed sentencing, a mounting body of evidence indicated that the wrong men had been apprehended. Key prosecution testimony was retracted and new evidence was produced that was favorable to the defendants. Herbert Ehrmann, a junior defense attorney, built a strong case against the Morelli gang of Providence, which specialized in stealing shipments from shoe manufacturers.

But the attitude of the authorities had become so rigidly set against the defendants that they turned a deaf ear to contrary views. Because of this, a growing number of observers, most of whom abhorred anarchism and had no sympathy with radical propaganda of any kind, concluded that the accused had not received a fair trial. The judge's bias against the defendants, their conviction on inconclusive evidence, their dignified behavior while their lives hung in the balance - all this attracted supporters, who labored to secure a new trial. At the eleventh hour, Governor Alvan T. Fuller conducted a review of the case, appointing an advisory committee, headed by President A. Lawrence Lowell of Harvard, to assist him. The Lowell Committee, as it became known, though finding Judge Thayer guilty of a "grave breach of official decorum" in his derogatory references to the defendants, nevertheless concluded that justice had been done.

As events moved towards a climax, the case assumed international proportions, engaging the passions of men and women around the globe. Anatole France, in one of his last public utterances, pleaded with America to save Sacco and Vanzetti: "Save them for your honor, for the honor of your children and for the generations yet unborn." In vain. On August 23, 1927, the men were electrocuted, in defiance of worldwide protests and appeals. By then, millions were convinced of their innocence, and millions more were convinced that, guilty or innocent, they had not received impartial justice.

With the passage of sixty years, one might have thought that everything that was likely to be known about the Sacco-Vanzetti affair had already been disclosed, every speculation laid to rest, every clue pursued to its inevitable dead end. Yet such a belief would be unwarranted. For, in spite of the unceasing flow of books about the case, it remains, as A. William Salomone has noted, a "great dark forest," large areas still unknown and unexplored. A deeper knowledge of the anarchist dimension, for example, of the social, political, and intellectual world in which the defendants lived and acted, would go far to explain their behavior on the night of their arrest, as well as the determination Of the authorities to convict them.

(17) Anthony Arthur, Radical Innocent : Upton Sinclair (2006)

It was Fred Moore, Sinclair said later, who confirmed his own growing doubts about Sacco's and Vanzetti's innocence. Meeting in a hotel room in Denver on his way home from Boston, he and Moore talked about the case. Moore said neither man ever admitted it to him, but he was certain of Sacco's guilt and fairly sure of Vanzetti's knowledge of the crime if not his complicity in it. This knowledge had not prevented Moore from doing whatever he could to save the two men, perhaps including illegal activities. The entire legal system was corrupt, Moore insisted, assuring Sinclair that "there is no criminal lawyer who has attained to fame in America except by inventing alibis and hiring witnesses. There is no other way to be a great criminal lawyer in America."

Sinclair's decision to end Boston on a note of ambiguity concerning the guilt or innocence of the Italian anarchists - as distinct from his treatment in Oil! of the Morgan bombing - subjected him to a torrent of abuse from the left. His old friend Robert Minor learned of Sinclair's intentions and called him in California, saying "You will ruin the movement! It will be treason!" Sinclair told Minor that he intended to tell the story "objectively," not omitting the existence of "direct actionists" - "direct action" being the left's euphemism for violence - in both the anarchist movement and the Communist Party. Minor then did charge Sinclair with treason to the socialist cause, with cowardice, and with outright lying. But Sinclair's refusal to bend the truth as he saw it won him unusual praise from less biased observers, even those who were sympathetic to Sacco and Vanzetti.