Donald Ogden Stewart

Donald Ogden Stewart, the son of a judge, was born in Columbus, Ohio, on 30th November, 1894. He attended Phillips Exeter Academy and Yale University, where he became friends with F. Scott Fitzgerald. According to Paul Buhle "he grew up shy... who nevertheless managed through geniality and wit to make himself liked at Yale." After leaving university he joined the Naval Reserves but did not serve in the armed forces during the First World War.

After the war Stewart moved to Greenwich Village with his widowed mother. Marion Meade has argued: "Stewart was in his mid-twenties, a likeable, attractive Ohioan who had established himself and his widowed mother in a tiny Village apartment. Bespectacled and prematurely balding, insecure and obsessed with money and success." Stewart became a journalist at Vanity Fair where he became a close friend of fellow employees, Dorothy Parker and Robert Benchley. It has been claimed by Brian Gallagher, the author of Anything Goes (1987) that the three became so close that: "Benchley, Parker and Don Stewart went so far as to open a joint bank account."

In 1920 he made his mark by publishing A Parody Outline of History, a satire on The Outline of History (1920) by H. G. Wells. Stewart began taking lunch with a group of writers in the dining room at the Algonquin Hotel in New York City. The writer, Murdock Pemberton, later recalled that he owner of the hotel, Frank Case, did what he could to encourage this gathering: "From then on we met there nearly every day, sitting in the south-west corner of the room. If more than four or six came, tables could be slid along to take care of the newcomers. we sat in that corner for a good many months... Frank Case, always astute, moved us over to a round table in the middle of the room and supplied free hors d'oeuvre. That, I might add, was no means cement for the gathering at any time... The table grew mainly because we then had common interests. We were all of the theatre or allied trades." Case admitted that he moved them to a central spot at a round table in the Rose Room, so others could watch them enjoy each other's company.

This group eventually became known as the Algonquin Round Table. Other regulars at these lunches included Robert E. Sherwood, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Alexander Woollcott, Heywood Broun, Harold Ross, Edna Ferber, Ruth Hale, Franklin Pierce Adams, Jane Grant, Neysa McMein, Alice Duer Miller, Charles MacArthur, Marc Connelly, George S. Kaufman, Beatrice Kaufman , Frank Crowninshield, Ben Hecht, John Peter Toohey, Lynn Fontanne, Alfred Lunt and Ina Claire.

Stewart became very close to Dorothy Parker. He later recalled: "Dottie was attractive to everybody - the eyes were so wonderful, and the smile. It wasn't difficult to fall in love with her. She was always ready to do anything, to take part in any party; she was ready for fun at any time when it came up, and it came up an awful lot in those days. She was fun to dance with and she danced very well, and I just felt good when I was with her, but I think if you had been married to Dottie, you would have found out, little by little, that she really wasn't there. She was in love with you, let's say, but it was her emotion; she was not worrying about your emotion. You couldn't put your finger on her. If you ever married her, you would find out eventually. She was both wide open and the goddamnedest fortress at the same time. Every girl's got her technique and shy, demure helplessness was part of Dottie's - the innocent, bright-eyed little girl that needs a male to help her across the street. She was so full of pretence herself that she could recognize the thing. That doesn't mean she did not hate sham on a high level, but that she could recognize pretence because that was part of her make-up. She would get glimpses of herself doing things that would make her hate herself for that sort of pretence."

Stewart had great success with his novel, Mr and Mrs Haddock Abroad (1924). That year he met Beatrice Ames, while in Paris. Beatrice was engaged to his old university friend, Harry Crocker. He later wrote: "She was living in Paris with her father, mother and younger sister Jerry, and I went to see her on the recommendation of my old Yale friend Harry Crocker who was engaged to her... I took Beatrice out on the Yale blue-plate special tour of Paris, including the royal box at Zellis, and ending up in the early morning at Les Halles for a spot of onion soup chez at Le Pere Tranquille. I concluded that Harry was a very lucky boy, but as she and her family left Paris almost immediately I didn't see her there again."

Beatrice later broke up her relationship with Crocker and decided to marry Stewart. He wrote in By a Stroke of Luck (1975): "We were both looking for marriage... Bea was young and beautiful, and I was very happy. She was a gay fun girl, loved parties and dancing, understood my kind of humor and had plenty of her own. Clara (his mother) and she got on together beautifully and I could hardly wait to introduce her to Bobby (Robert Blenchley) and Dottie (Dorothy Parker)." In fact she remained friends with Dorothy Parker for the next forty years.

Robert Benchley and Marc Connelly both attended the wedding: "The wedding was to be held in a fashionable small church in Santa Barbara's suburb, Carpentaria. Don's mother had come out from Ohio for the wedding and had been living near my mother in Hollywood. Benchley was to be best man and I an usher. The day before the wedding we two drove up to Santa Barbara for a party. To make the next day's two-hour drive as comfortable as possible for Mrs. Stewart and my mother, I asked Hollywood's leading car-rental company to provide their best chauffeur-driven limousine. Because many motion-picture stars were expected as guests, all cars arriving at the church received the attention of a crowd of spectators."

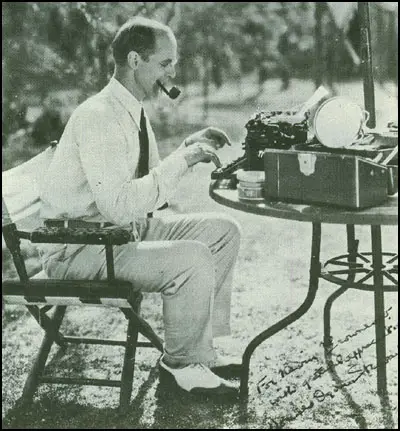

Stewart published the novel, The Crazy Fool in 1925. He adapted the book as a film, Brown of Harvard (1926). He moved to Hollywood in 1930. Over the next few years he worked on twenty-five films including Laughter (1930), Finn and Hattie (1931), Tarnished Lady (1931), Rebound (1931), Smilin' Through (1932), The White Sister (1933), Another Language (1933) and The Barretts of Wimpole Street (1934).

The authors of Radical Hollywood: The Untold Story Behind America's Favorite Movies (2002) have argued: "Romantic comedy work allowed Stewart to develop cinematic themes that had deep emotional importance for him and went to the heart of his highest success - not forgetting his ability to write snappy dialogue, much of it ridiculing upper-class manners... Stewart's work suggested well before his conscious radicalization that through the intimacy of marriage, people found their capacity of sacrifice to something larger than themselves, something approaching a small-scale model for a cooperative society. Disguised in his dialogue as soigné sophistication and world-weariness, the message carried with it possibilities that women viewers in particular could readily understand." The film critic, Cedric Belfrage, argued that Stewart, Dorothy Parker and Robert Benchley were using Hollywood to promote a radical message: "The art of subversion through laughter had its sophisticated practitioners in Dorothy Parker, Donald Ogden Stewart and Robert Benchley."

Stewart was converted to socialism by The Coming Struggle for Power by John Strachey. "It suddenly came over me that I was on the wrong side. If there was this class war as they claimed, I had somehow got into the enemy's army. I felt a tremendous sense of relief and exultation. I felt I had the answer I had been so long searching for. I now had a cause to which I could devote all my gifts for the rest of my life. I was once more beside grandfather Ogden who had helped to free the slaves. I felt clean and happy and exalted. I had won all the money and status that America had to offer - and it just hadn't been good enough. The next step was Socialism."

In 1936 Stewart and Dorothy Parker met a former Berlin journalist, Otto Katz. He told them about what was happening in Nazi Germany. Stewart recalled that when Katz began to describe the rule of Adolf Hitler "the details of which he had been able to collect only through repeatedly risking his own life, I was proud to be sitting beside him, proud to be on his side in the fight." Stewart and Parker decided to join with a group of people involved in the film industry who were concerned about the growth of fascism in Europe to establish the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League (HANL). Members included Alan Campbell, Walter Wanger, Dashiell Hammett, Cedric Belfrage, John Howard Lawson, Clifford Odets, Dudley Nichols, Frederic March, Lewis Milestone, Oscar Hammerstein II, Ernst Lubitsch, Mervyn LeRoy, Gloria Stuart, Sylvia Sidney, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Chico Marx, Benny Goodman, Fred MacMurray and Eddie Cantor.

Stewart joined the American Communist Party. He later recalled in his autobiography: "I didn't want to stop dancing or enjoying the fun and play in life. I wanted to do something about the problem of seeing to it that a great many more people were allowed into the amusement park. My new-found philosophy was an affirmation of the good life, not a rejection of it." John Keats has pointed out: "One story that went the rounds was that Mr Stewart was hit by a truck as he crossed a street, suffered a concussion, and discovered when he woke up in hospital that he had become a Communist."

Stewart was also a member of the Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee and the Motion Picture Artists Committee to Aid Republican Spain. He also became president of the League of American Writers (LAW), an organization that attempted "to get writers out of their ivory towers and into the active struggle against Nazism and Fascism." Stewart lost a lot of friends who disapproved of his political activities. Robert Benchley claimed that "Don (Stewart) became pretty difficult in past two years, all wrapped up in his guilds and leagues and soviets." His wife, Beatrice Ames Stewart, also disapproved of these political activities.

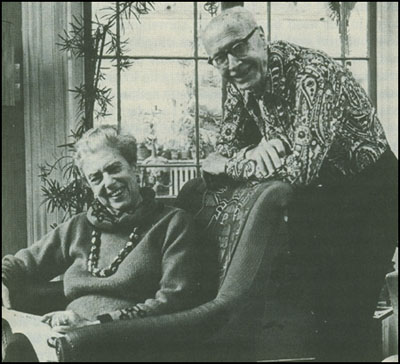

At a conference in November 1937, Stewart met the writer, Ella Winter. She was introduced as the widow of Lincoln Steffens: "I dimly remembered from my youth Steffens' muckraking articles in father's bound volumes of McClure's magazine, and I awaited gray hair and a few sad but brave wrinkles. To my astonishment, there came to the front of the platform a handsome middle-aged brunette who had the most extraordinary black eyes, alternately luminous and flashing as she spoke in a charming British voice." In her speech she "welcomed especially the humorists who had come from Hollywood, because what the Movement needs is humor, humor and more humor," and added "Dorothy Parker and Donald Ogden Stewart in one sentence can help us more than a thousand jargon-filled pamphlets."

Ella Winter described their first meeting in her autobiography, And Not to Yield (1963): "He was tall and slender and very graceful, with blond hair and blue eyes that very often held a puckish look like that of a wise and naughty child. Humorous and gentle, shy and warmhearted, Don was strangely untouched by the Hollywood he had lived and worked in for some years.... He had lately become passionately interested in what was happening politically in Europe, the United States, Germany, California; he read hungrily, and was fascinated by my experiences."

Beatrice Ames Stewart began an affair with Count Ilya Andreyevich Tolstoy. Stewart was also romantically involved with Ella Winter and in 1938 Beatrice asked him for a divorce. Stewart recorded in By a Stroke of Luck (1975): "When I got back from holiday my wife had news for me. She came to the farm on Mothers' Day to tell me that she wanted a divorce in order to marry Count Ilya Tolstoy, a grandson of the writer and a 'defectee' from the Soviet Union whose government had sent him a year or two previously to an Iowa Agricultural College in order to perfect himself in the art of raising horses for the Russian farmers. I had had no suspicion of anything. My enthusiasm for my own 'rebirth,' which I had hoped would make her love me all the more, had blinded me to the fact that we had been drifting apart for some time. In the meantime I had fallen in love with Ella (Winter) and she with me. But I also loved Bea, and would not have left her. She was my wife and the habit of marriage to her was strong. Everything in the house was a reminder of her. I was momentarily angry at her 'desertion,' especially at a time when I was becoming increasingly isolated because of my beliefs. My pride was also hurt. But she convinced me that in Tolstoy she had found her real love, and I agreed to her request."

In 1938 the couple divorced. "Bea meanwhile had successfully obtained a Florida divorce and I was free to marry Ella. There was, however, one small hitch: She wasn't in any particular hurry to get married. Her hesitancy arose partly out of concern over presenting without careful preparation her eleven-year-old son, Pete Steffens, with a stepfather. The relationship between Pete and Lincoln Steffens had been extremely tender and close." Stewart eventually married Ella Winter in 1939.

In August 1939, Joseph Stalin and Adolf Hitler signed the Soviet-Nazi Pact. Soon afterwards Hitler gave orders for the invasion of Poland. This forced Neville Chamberlain to declare war on Nazi Germany, therefore starting the Second World War. Three weeks later Stalin ordered the Red Army to invade Poland from the east, meeting the Germans in the centre of the country. The leaders of the American Communist Party accepted Stalin's message that the war was not against fascism but just another "imperialist war between capitalistic nations".

Under the influence of the American Communist Party, the League of American Writers supported Stalin's new foreign policy. Most members left the organisation in disgust but Winter and Stewart remained loyal. As Stewart explained in By a Stroke of Luck (1975): "I just couldn't be unfaithful to my friends or my side. So I didn't denounce any Communist-controlled organizations of which I was president or to which my name was helpful. My growing doubts about the American Communist Party's interpretation of Marxism didn't affect my belief in the superior wisdom of the remote Soviet Union which, being so distant, in no way challenged my personal ethics."

Throughout this period Stewart continued to work in Hollywood. His films included The Prisoner of Zenda (1937), Holiday (1938), Marie Antoinette (1938), Love Affair (1939), The Night of Nights (1939), Kitty Foyle (1940) and the Academy Award winning The Philadelphia Story (1940), That Uncertain Feeling (1941) and A Woman's Face (1941).

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared war on Japan, Stewart and Ella Winter were recruited by Archibald MacLeish, head of the Office of War Information. This included writing speeches for "War Administration big shots" and scripts for war propaganda radio programmes. Stewart was especially proud of a script he wrote for a radio documentary: "I chose as my subject an actual happening in a small Ohio town where, in a truly joint effort, each person contributed labor according to his or her ability. For the first few weeks, the war effort became democratic in the sense in which I hoped all of America might some day become, that is, of people working together in equality and for each other instead of competing in a rat race for financial security and status." However, it was considered too left-wing and was never broadcast.

In 1942 Stewart began working with I. A. R. Wylie, who had just published a novel entitled, Keeper of the Flame, that had been inspired by the activities of Charles Lindbergh and the America First Committee. Stewart later recalled: "The Keeper of the Flame was perfectly made for my desire to contribute to an understanding of democracy's war by exposing the danger of un-Americanism within our own gates. The story begins with the five-star funeral in a small town of one of America's favorite sons, someone like, say, General MacArthur. Spencer Tracy is a New York reporter who has been sent to cover the event and attempts in vain to obtain an interview with the widow (played by Katharine Hepburn). Accidently they meet, and he becomes increasingly suspicious that the lady is not telling the true story about her husband's death. Finally he becomes convinced that in some way she was responsible (for the death of her husband)." Eventually she confesses that she had not saved her husband from the accident because "Her husband, the great national hero, had become the spearhead of a plot to overthrow the Roosevelt-like government and substitute a Mussolini-type dictatorship... The backers of this coup were a group in the extension of the power of the people a dangerous challenge to their own type of Free World. The plot had in those days strikingly believable parallels, including Hitler's successful takeover of his country with the backing of Krupp, Thiessen and other powerful Germans."

The film, Keeper of the Flame, directed by George Cukor, was screened for the Office of War Information's Bureau of Motion Pictures on 2nd December, 1942. The Bureau's chief, Lowell Mellett, was unhappy with the picture and disapproved of its anti-capitalist message. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer head Louis B. Mayer, also hated the movie, as he felt it equated wealth with fascism. Stewart claimed that Meyer "walked out in a fury" of the New York City premiere "when he discovered, apparently for the first time, when the picture was really about". Republican Party members of Congress complained about the film's left-wing message and demanded that Will H. Hays, President of the Motion Picture Production Code, establish guidelines regarding propagandization for the motion picture industry.

Stewart regarded Keeper of the Flame as "the most radical film of his that Hollywood could accept. The authors of Radical Hollywood: The Untold Story Behind America's Favorite Movies (2002) have pointed out: "Keeper of the Flame is a brilliant and badly underrated film, not only because Tracy draws out Hepburn step by step, raising her confidence in herself rather than breaking her down, but also because the familiar idea of rich and ruthless totalitarians attains here as high a statement ever made in a major film." Martha Nochimson, has argued in Screen Couple Chemistry (2002) that the film is a "truly provocative in that it was one of Hollywood's few forays into imagining the possibility of homegrown American Fascism and the crucial damage which can be done to individual rights when inhumane and tyrannical ideas sweep a society through a charismatic leader."

Stewart continued to produce film-scripts for Hollywood that included Forever and a Day (1943), Without Love (1945), Life with Father (1947), Cass Timberlane (1947) and Edward, My Son (1949). However, it was his anti-fascist film, Keeper of the Flame, that brought him to the attention of the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) that was investigating the entertainment industry after the Second World War.

In June, 1950, three former FBI agents and a right-wing television producer, Vincent Harnett, published Red Channels, a pamphlet listing the names of 151 writers, directors and performers who they claimed had been members of subversive organisations before the Second World War. The names had been compiled from FBI files and a detailed analysis of the Daily Worker, a newspaper published by the American Communist Party. The list included Stewart. A free copy was sent to those involved in employing people in the entertainment industry. All those people named in the pamphlet were blacklisted until they appeared in front of the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and convinced its members they had completely renounced their radical past. Stewart was now blacklisted.

Dorothy Parker and Alan Campbell were also on the list. The couple left Hollywood and moved back to New York City. In April 1951, Parker and Campbell were visited by two FBI agents. They asked if they knew Stewart, Ella Winter, Dashiell Hammett, Lillian Hellman, Ella Winter and John Howard Lawson and if they had attended meetings of the American Communist Party with them. The agents reported: "She (Parker) was a very nervous type of person... During the course of this interview, she denied ever having been affiliated with, having donated to, or being contacted by a representative of the Communist Party."

Stewart and Ella Winter decided to move to England and rented the former house of Ramsay MacDonald at 103 Frognal, Hampstead. According to Norma Barzman, the actress, Katharine Hepburn, helped the Stewarts to renovate the house: "Its condition was so wretched the owners, the former prime minister's family, felt they couldn't ask for rent. Katharine Hepburn, the Stewarts' bosom friend for years, took one look at the house, said it was beautiful, came over every day for six weeks with a packed lunch from the Connaught Hotel, and helped Ella fix it up."

Over the next few years Stewart wrote for British television or used a false name to write movies. This included Summertime (1955), An Affair to Remember (1957), The Kidders (1958) and Moment of Danger (1960). Stewart also published an autobiography, By a Stroke of Luck (1975).

Donald Ogden Stewart died in London on 2nd August 1980. His wife, Ella Winter, died two days later.

Primary Sources

(1) In his autobiography, By a Stroke of Luck, David Ogden Stewart explained how he became a socialist by reading The Coming Struggle for Power by John Strachey.

It suddenly came over me that I was on the wrong side. If there was this "class war" as they claimed, I had somehow got into the enemy's army. I felt a tremendous sense of relief and exultation. I felt I had the answer I had been so long searching for. I now had a cause to which I could devote all my gifts for the rest of my life. I was once more beside grandfather Ogden who had helped to free the slaves. I felt clean and happy and exalted. I had won all the money and status that America had to offer - and it just hadn't been good enough. The next step was Socialism.

(2) Marc Connelly, Voices Offstage (1968)

There was another occasion that summer when my mother became socially conspicuous. Donald Ogden Stewart had become engaged to Beatrice Ames, daughter of a prominent Santa Barbara family. The wedding was to be held in a fashionable small church in Santa Barbara's suburb, Carpentaria. Don's mother had come out from Ohio for the wedding and had been living near my mother in Hollywood.

Benchley was to be best man and I an usher. The day before the wedding we two drove up to Santa Barbara for a party. To make the next day's two-hour drive as comfortable as possible for Mrs. Stewart and my mother, I asked Hollywood's leading car-rental company to provide their best chauffeur-driven limousine. Because many motion-picture stars were expected as guests, all cars arriving at the church received the attention of a crowd of spectators. I was in the doorway when Mrs. Stewart and my mother alighted from a handsome Hispano-Suiza. On alighting they were not identified by the celebrity hunters. The hearty laughter they heard as the car drove off made them look back at it. The politically conscious rental company had attached to the back of the limousine an enormous poster reading: "Vote for Clyde Zimmer for sheriff."

(3) Ella Winter, And Not to Yield (1963)

I do not suppose I could have been drawn to anyone who did not share my larger concerns. Don had become newly aware in the past few years of social questions, and it was all still fresh and challenging to him. He was tall and slender and very graceful, with blond hair and blue eyes that very often held a puckish look like that of a wise and naughty child. Humorous and gentle, shy and warmhearted, Don was strangely untouched by the Hollywood he had lived and worked in for some years. He was a gifted and humorous writer and talker, and he loved gaiety, cheerful people - a "gala" atmosphere, as he called it. He had lately become passionately interested in what was happening politically in Europe, the United States, Germany, California; he read hungrily, and was fascinated by my experiences. Radicals at this time were frequently charged with "boring from within," and when eventually Don and I began seeing more of each other, our friends were gaily malicious at what they thought of as the double success of my efforts -one was supposed only to influence ideas, not the holder of them.

Don was born in Columbus, Ohio, and he had characteristic American traits, from an outward conformism to a consuming interest in the World Series. But he had a rare courage and independence of mind, and a stubborn, almost puritan, integrity, which withstood all blandishments. (I soon dubbed him John Knox.) When he believed in something, he felt he must act on his beliefs. He was making speeches for the Hollywood anti-Nazi movement in out-of-the-way halls or on the piers of Venice or Santa Monica, unostentatiously and with an unconcern for possible effects on his Hollywood position. As the movement grew in the film colony, he was called on more and more to chair meetings - his spontaneous humor made him a witty, popular speaker and toastmaster-and to sign an increasing number of protests and petitions. His sponsorship of so many committees and delegations gave rise to a satiric story: when President Roosevelt awoke in the morning, he would ring for his orange juice, his coffee, and "the first eleven telegrams from Donald Ogden Stewart."