Robert Blenchley

Robert's older brother, Edmund, was killed during the Spanish-American War. It has been claimed by Brian Gallagher that he heard his mother say on hearing of Edmund's death screaming "Oh, why couldn't have been Robert?". Gallagher argues that this incident gave him a great desire to be loved. It has also been suggested that it helped influence his anti-war views. It has been pointed out that after his brother's death his mother brought him up as a pacifist. Benchley was educated at Harvard University and married Gertrude Darling in June 1914. His wife had two children Nathaniel (1915) and Robert (1919).

After leaving university Benchley tried very hard to become a journalist. He did freelance work for Vanity Fair before Ernest Gruening recruited him to work for the New York Tribune. Benchley, who by this time was a pacifist, wrote critically about the First World War. On 7th June 1918 he wrote an article in praise of African-American regiments on the Western Front. Gruening later explained in his autobiograpy, Many Battles (1973) what happened: "On Sunday, June 7, he scheduled a half-page picture of a contingent of Negroes of Colonel Hayward's 169th Infantry which had distinguished itself in recent engagements in France, and two of whom - their pictures were shown separately - had been decorated with the Croix de Guerre for bravery in action. As the page was being made up, Bob received a photograph of the lynching of a Negro man in Georgia being witnessed by a large crowd. Bob thought that running these pictures together might prove useful as a plea for racial tolerance and I agreed."

The photograph of the lynching in Georgia with the article on the soldiers who had won the Croix de Guerre caused problems for Benchley with Garet Garrett, the executive editor of the newspaper. Benchley's son, Nathaniel Benchley, later pointed out: "The page went to press.... and the first copy hadn't been upstairs more than three minutes when there was a dropping of pencils, a ringing of bells, and then a great clanking sigh of the presses ground to an emergency stop. Robert was summoned down to the office of Garet Garrett and there he found Garrett, Rogers and Ogden Reid, the Editor in Chief standing in a semi-circle and looking with frozen horror at the lynching picture. He was told it was pro-German, that it was a terrible thing to run "at this time" and that he would damned well get another picture to replace it because the Alco Company had already been notified to make a new press cylinder."

Benchley continued to have problems with the executive editor of the New York Tribune. "Garrett began to criticize Robert's choice of pictures with remarkable vigor... He and Gruening had a long argument about a picture of the Kaiser that Robert had run, Garrett maintaining that to show the Kaiser as a normal human being, walking down the street, tended to weaken the public's hate for him. The policy was that any picture that showed a German not cutting off a child's hand was a bad picture. Gruening disagreed and told Garrett exactly what he thought of such a policy, but it had no effect. Three days later Garrett pounced on a picture Robert had scheduled... showing a U-boat crew picking up survivors of a ship they had torpedoed. This, it seemed, was as good as a pro-German picture, because they weren't machine gunning the survivors." As a result of this interference, Benchley and Gruening resigned from the newspaper.

In May 1919, Frank Crowninshield, the editor of Vanity Fair, appointed Benchley as managing editor of the magazine on $100 a week. John Keats, the author of You Might as Well Live: The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1971) has pointed out that Dorothy Parker, a fellow worker on the magazine, soon became a close friend: "He (Benchley) was one of the few people of this world for whom no one could find an unpleasant word, and not a few of his friends said that his simple presence in a room made everyone feel better. The essence of Mr. Benchley's charm lay in his delightfully oblique view of the world, through which he made his way in a kind of hopeful desperation."

At Vanity Fair Benchley worked alongside Robert E. Sherwood and Dorothy Parker. As Harriet Hyman Alonso has pointed out: "Benchley was a man whom Bob had admired since first seeing him at Harvard, where Benchley was a student in the class of 1912. At Bob's freshman smoker he gave the featured speech and then spent time with the new students, drinking beer, smoking, and generally joking around. Benchley also served as president of the Harvard Lampoon and wrote scripts for several of the Hasty Pudding shows." During this period he began having lunch with Parker and Sherwood in the dining room at the Algonquin Hotel. Sherwood was six feet eight inches tall and Benchley was also over six feet tall. Parker, who was five feet four inches, once commented that when she, Sherwood and Benchley walked down the street together, they looked like "a walking pipe organ."

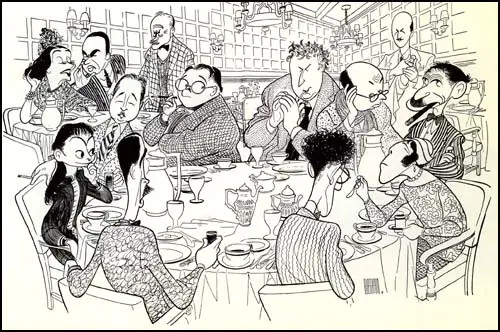

According to Harriet Hyman Alonso , the author of Robert E. Sherwood The Playwright in Peace and War (2007): "John Peter Toohey, a theater publicist, and Murdock Pemberton, a press agent, decided to throw a mock "welcome home from the war" celebration for the egotistical, sharp-tongued columnist Alexander Woollcott. The idea was really for theater journalists to roast Woollcott in revenge for his continual self-promotion and his refusal to boost the careers of potential rising stars on Broadway. On the designated day, the Algonquin dining room was festooned with banners. On each table was a program which misspelled Woollcott's name and poked fun at the fact that he and fellow writers Franklin Pierce Adams (F.P.A.) and Harold Ross had sat out the war in Paris as staff members of the army's weekly newspaper, the Stars and Stripes, which Bob had read in the trenches. But it is difficult to embarrass someone who thinks well of himself, and Woollcott beamed at all the attention he received. The guests enjoyed themselves so much that John Toohey suggested they meet again, and so the custom was born that a group of regulars would lunch together every day at the Algonquin Hotel."

Murdock Pemberton later recalled that he owner of the hotel, Frank Case, did what he could to encourage this gathering: "From then on we met there nearly every day, sitting in the south-west corner of the room. If more than four or six came, tables could be slid along to take care of the newcomers. we sat in that corner for a good many months... Frank Case, always astute, moved us over to a round table in the middle of the room and supplied free hors d'oeuvre.... The table grew mainly because we then had common interests. We were all of the theatre or allied trades." Case admitted that he moved them to a central spot at a round table in the Rose Room, so others could watch them enjoy each other's company.

The people who attended these lunches included Benchley, Robert E. Sherwood, Dorothy Parker, Alexander Woollcott, Heywood Broun, Harold Ross, Donald Ogden Stewart, Edna Ferber, Ruth Hale, Franklin Pierce Adams, Jane Grant, Neysa McMein, Alice Duer Miller, Charles MacArthur, Marc Connelly, George S. Kaufman, Beatrice Kaufman , Frank Crowninshield, Ben Hecht, John Peter Toohey, Lynn Fontanne, Alfred Lunt and Ina Claire. This group eventually became known as the Algonquin Round Table.

The group played games while they were at the hotel. One of the most popular was "I can give you a sentence". This involved each member taking a multi syllabic word and turning it into a pun within ten seconds. Dorothy Parker was the best at this game. For "horticulture" she came up with, "You can lead a whore to culture, but you can't make her think." Another contribution was "The penis is mightier than the sword." They also played other guessing games such as "Murder" and "Twenty Questions". A fellow member, Alexander Woollcott, called Parker "a combination of Little Nell and Lady Macbeth."

Dorothy Parker developed a reputation for making harsh comments in her reviews and on 12th January 1920 she was sacked by Frank Crowninshield, the editor of Vanity Fair. He told her that complaints about her reviews had come from three important theatre producers. Florenz Ziegfeld was particularly upset by Parker's comments about his wife, Billie Burke: "Miss Burke is at her best in her more serious moments; in her desire to convey the girlishness of the character, she plays her lighter scenes as if she were giving an impersonation of Eva Tanguay."

Benchley and Robert E. Sherwood both resigned over the sacking. As John Keats, the author of You Might as Well Live: The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1971): "It is difficult now to imagine a magazine of Vanity Fair's importance then truckling to Broadway producers, but the newspapers and magazines of 1920 did, and this was a sore point to the working newspapermen and theatre critics at the Round Table. They believed that if an actor was guilty of overacting, it was no more and no less than a critic's duty to report that he was - producers be damned. Furthermore, in this case, Vanity Fair's position seemed to be one of accepting a complaint from an advertiser as sufficient excuse to fire an employee with no questions asked, and it was the injustice of this position that led Mr Benchley and Mr Sherwood to tell Mr Crowninshield that if he was going to fire Mrs Parker, they were quitting."

Parker and Benchley rented a small office together. Benchley later commented: "One cubic footless of space, and it would have constituted adultery." A few weeks later he abandoned the economically precarious existence of a free-lance writer and accepted the post as drama editor on Life Magazine. It was said that after Benchley left, Parker was very lonely and she decided to move in with the artist, Neysa McMein as her relationship with her husband was over. Donald Ogden Stewart commented: "It was a case of incompatibility. It just didn't work. When we got back from Germany, it was already over."

On 30th April 1922, the Algonquin Round Tablers produced their own one-night vaudeville review, No Siree!: An Anonymous Entertainment by the Vicious Circle of the Hotel Algonquin . It included a monologue by Robert Benchley, entitled The Treasurer's Report . Marc Connelly and George S. Kaufman contributed a three-act mini-play, Big Casino Is Little Casino, that featured Robert E. Sherwood. The show included several musical numbers, some written by Irving Berlin. One of the most loved aspects of the show was the Dorothy Parker penned musical numbers that were sang by Tallulah Bankhead, Helen Hayes, June Walker and Mary Brandon.

Samuel Hopkins Adams, the author of Alexander Woollcott: His Life and His World (1946), has argued: "The Algonquin profited mightily by the literary atmosphere, and Frank Case evinced his gratitude by fitting out a workroom where Broun could hammer out his copy and Benchley could change into the dinner coat which he ceremonially wore to all openings. Woollcott and Franklin Pierce Adams enjoyed transient rights to these quarters. Later Case set aside a poker room for the whole membership."

In 1925 he began working for The New Yorker, a new magazine established by his friend, Harold Ross. Four years later he began its theatre critic. Robert Blenchley was considered to be one of America's leading journalists. However, he ruefully admitted that "it took me fifteen years to discover that I had no talent for writing, but I couldn't give it up because by then I was too famous."

Blenchley also did work in Hollywood and acted in his first feature film, The Sport Parade in 1932. Benchley also wrote and directed humorous short-films such as How to Sleep (1936) that earned him an Academy Award. This was followed by How to Train a Dog (1936), How to Behave (1936) and A Night at the Movies (1937).

Robert Benchley, a heavy drinker, died of cirrhosis of the liver on 21st November, 1945.

Primary Sources

(1) Ernest Gruening, Many Battles (1973)

On Sunday, June 7, he scheduled a half-page picture of a contingent of Negroes of Colonel Hayward's 169th Infantry which had distinguished itself in recent engagements in France, and two of whom - their pictures were shown separately - had been decorated with the Croix de Guerre for bravery in action. As the page was being made up, Bob received a photograph of the lynching of a Negro man in Georgia being witnessed by a large crowd. Bob thought that running these pictures together might prove useful as a plea for racial tolerance and I agreed.

(2) Nathaniel Benchley, Robert Benchley: A Biography (1955)

The page went to press.... and the first copy hadn't been upstairs more than three minutes when there was a dropping of pencils, a ringing of bells, and then a great clanking sigh of the presses ground to an emergency stop. Robert was summoned down to the office of Garet Garrett and there he found Garrett, Rogers and Ogden Reid, the Editor in Chief standing in a semi-circle and looking with frozen horror at the lynching picture. He was told it was pro-German, that it was a terrible thing to run "at this time" and that he would damned well get another picture to replace it because the Alco Company had already been notified to make a new press cylinder...

Garrett began to criticize Robert's choice of pictures with remarkable vigor... He and Gruening had a long argument about a picture of the Kaiser that Robert had run, Garrett maintaining that to show the Kaiser as a normal human being, walking down the street, tended to weaken the public's hate for him. The policy was that any picture that showed a German not cutting off a child's hand was a bad picture. Gruening disagreed and told Garrett exactly what he thought of such a policy, but it had no effect. Three days later Garrett pounced on a picture Robert had scheduled... showing a U-boat crew picking up survivors of a ship they had torpedoed. This, it seemed, was as good as a pro-German picture, because they weren't machine gunning the survivors.

(3) Harriet Hyman Alonso, Robert E. Sherwood The Playwright in Peace and War (2007)

Benchley was a man whom Bob had admired since first seeing him at Harvard, where Benchley was a student in the class of 1912. At Bob's freshman smoker he gave the featured speech and then spent time with the new students, drinking beer, smoking, and generally joking around. Benchley also served as president of the Harvard Lampoon and wrote scripts for several of the Hasty Pudding shows. "It gave me a particular thrill to see Benchley," Bob recalled of his college years, "because I had every intention of stepping into his boots." Benchley had become Bob's role model, "a shining objective toward which to strive as an undergraduate," though one he felt he "never even approached" throughout his entire career. After World War I ended, Bob had another reason to admire Benchley; he had been raised by his mother to be a pacifist after his brother Edmund, thirteen years his senior, was killed in action during the Spanish-American War.

(4) John Keats, You Might as Well Live: The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1971)

He (Benchley) was one of the few people of this world for whom no one could find an unpleasant word, and not a few of his friends said that his simple presence in a room made everyone feel better. The essence of Mr. Benchley's charm lay in his delightfully oblique view of the world, through which he made his way in a kind of hopeful desperation.

© John Simkin, April 2013